Deconstructing the Image

Montmartre, 1900

In 1900, Montmartre was a semi-rural hill just north of Paris where working people lived, worked, and gathered in taverns and dance halls. A disparate group of artists collaborated there, many living and painting in le Bateaux-Lavoir, a derelict factory space with cheap rent, space for painting but no running water. The artists who lived and worked there and drank in taverns such as the Lapin Agile gave birth to what became known as Modern Art.

|

| Le Bateaux-Lavoir. (c. 1910). Anonymous Photograph. |

We have seen how Classical and Renaissance artists pursued meticulous imitation of visual subjects in perspective. And we have seen Impressionism move from naturalistic mimesis to subjectivity of vision. As the 20th Century dawned, revolutionary artists in Paris began to dramatically distort and deconstruct images in pursuit of very different aesthetic values.

So buckle your seatbelts. For more than 120 years, people have been shrinking from the challenges of “modern art.” Remember—you are never required to like anything in our class. But let’s try to get a grip on the games that these artists are playing.

Henri Matisse and Fauvism

As is so often the case, the term Fauvism was originally used to by disapproving critics to disparage the savages led by Henri Matisse[1]:

Fauvism: a movement … based on the use of intensely vivid, non-naturalistic colors. … Henri Matisse used vividly contrasting colors … and came to realize the potential of color freed from its traditional descriptive role. … The Fauves … name was given to them by critic Louis Vauxcelles who pointed to a Renaissance-like sculpture in the middle of the same gallery and exclaimed: “Donatello au milieu des fauves!” (Donatello among the wild beasts). … Fauvist pictures came in for a good deal of mockery and abuse; critic Camille Mauclair … wrote that “A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public” (Fauvism).

[1] For more information on Matisse, follow up with this article.

Taking his cue especially from Cézanne, Matisse radically challenged the Renaissance idea that a painting functioned as a window on the world. His famous work, La Danse depicts lively women. But they dance outside of time on a shapeless, dislocated green space. While depth is inscribed in the dancers’ circle, the rest of the image has been flattened to eliminate linear perspective. Figures are rendered with a few deft sketch lines and sheer colors dominate.

|

|

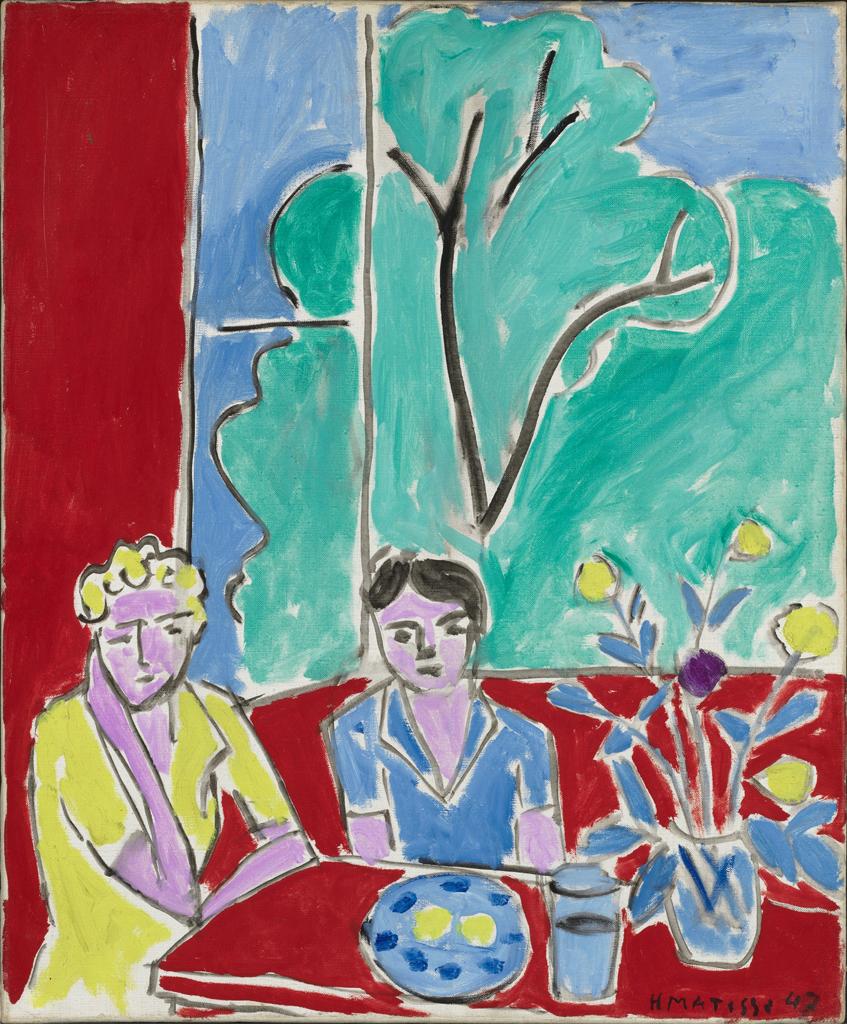

| La Danse (first version). (1909).Oil on canvas. | (1948). Two Girls, Red and Green Background. Oil on canvas. |

During the Renaissance, hundreds of portraits included veduta: interior spaces with windows opening onto landscapes. Matisse’s Two Girls, Red and Green Background reinvents the genre. Perspective has evaporated, leaving a flat image into which our visual imaginations somehow project the depth that has to be there. Pure color dominates the image, and not in any naturalistic sense. The red of the table blends seamlessly into the identical red of the dimensionless walls, playing off against pastel yellows, blues, and greens. With Matisse, the game is color, often strange, unnatural, sometimes bilious color, and free flowing forms.

Picasso and Cubism

Barcelona native Pablo Picasso first visited Paris in 1900, settling into le Bateaux-Lavoir for a decade. Picasso’s time at le Bateaux-Lavoir was interrupted a few times by trips home to Barcelona to replenish his purse and restore his confidence as his circle of devotees stubbornly refused to grow sufficiently to lift him out of poverty. He struggled to find a style that would express his imagination … and sell!

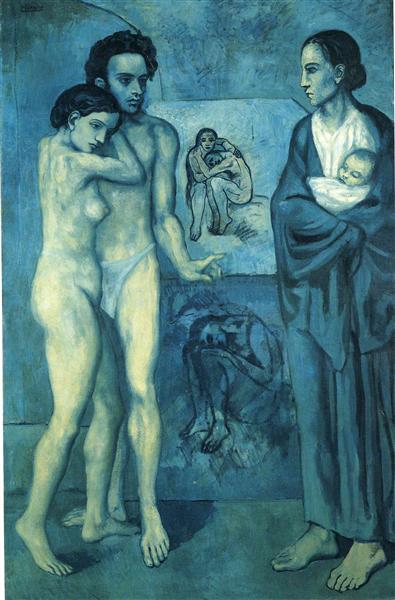

Picasso’s reputation for bewildering visual puzzles scares off many viewers. However, if one looked only at the Blue Period, one might ask what all the fuss was about. The long, lean figures are austere but elegant, quiet celebrations of the lives of the working poor.

|

|

|

| Woman Ironing. (1904). Oil on canvas. | La Vie. (1904) Oil on canvas. | Old Guitarist. (1904). Oil on panel. |

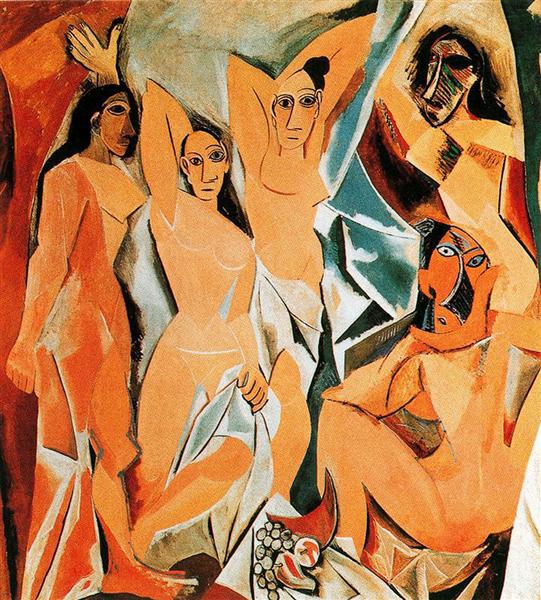

But of course Picasso didn’t stop there. Around 1905, Picasso began a year’s work on a large canvas that he showed no one until it was finished. Like many works of art that change the game forever, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was not received well initially, even by friends and collaborators. The piece challenges us to think hard about what we are seeing.

|

| Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Oil on canvas. |

Some elements of the painting are traditional. The subject matter is straightforward, if a bit sordid: the women of a brothel in Montmartre. Notice the fruit, typical components of a Still Life. The faces of the two central women are drawn in the traditional style of Spanish folk art. But what of those other two faces?

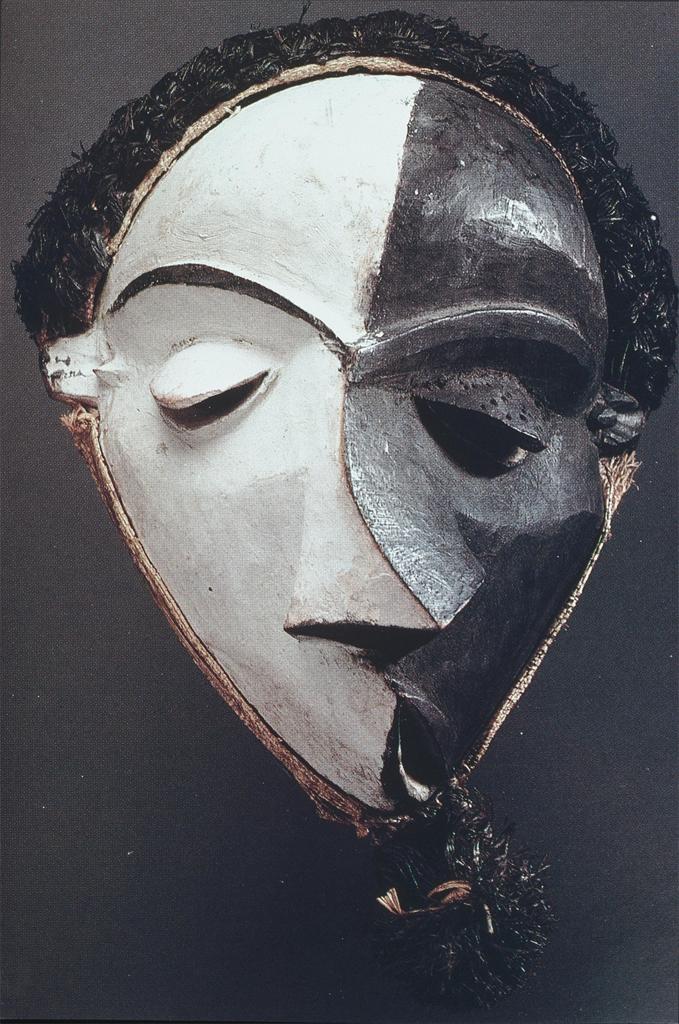

Our first clue rises lies in the angular, geometric features of ritual masks from African cultures. African art was at the time becoming popular among artists and sophisticated people in Paris and New York. Picasso was fascinated by the way these conventions broke the image of a face into roughly geometrical shapes. He felt liberated to fracture a composition into disparate pieces, reflecting different styles. The features of the lowest face are dramatically stylized and portrayed from multiple perspectives. This approach to presenting a human face became an often parodied trademark, but we should remember that Egyptian paintings also confront us with contrasting perspectives: profiles except for torso and eyes.

|

|

|

| Kagle Mask. Dan People. | Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, detail. | Pende Mbuyu (Sickness) Mask. Painted wood, fiber, cloth. |

The deconstruction of figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon led Picasso and his close friend Georges Braque to develop a cubist approach to painting:

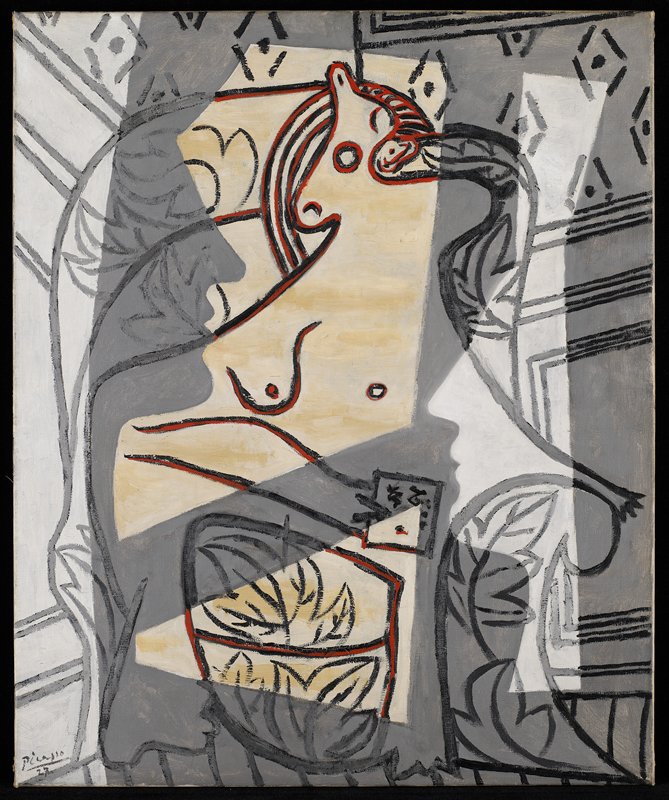

An analytical cubist piece like Ma Jolie includes some elements of recognizable subjects. Can you see the woman or the guitar? But the elements of an image are fractured and reassembled in an almost completely formal composition, playing with line, figure, and value.

| |

|

|

| Georges Braque. (1913). Woman with a Guitar. Oil on Canvas. | Picasso. (1907). Ma Jolie (Femme a la guitare). Oil on Canvas. | Picasso. (1907) Woman in an Armchair. Oil on canvas. |

Picasso rather quickly moved on to experiment more and more daringly with deconstructed images. Woman in an Armchair deconstructs commonplace subjects and reassembles them in extraordinary complexity. The piece works as a visual puzzle, with the woman being depicted from many perspectives at once: can you see the facing profiles? Notice how the lines of the trim on the wall create compositional lines that flatten linear perspective.

In 1936, Picasso’s native Spain erupted into civil war. The fascist forces of Francisco Franco were heavily supported by Adolf Hitler’s German military. On April 26th, 1937, the Luftwaffe [Air Force of Nazi Germany] bombed the Spanish town of Guernica, killing hundreds, if not thousands, and inspiring perhaps the world’s greatest protest painting: Picasso’s Guernica.

|

| Guernica. (1939). Oil on Canvas. |

Picasso composed Guernica to exorcise his profound distress in reading newspaper articles about the slaughter of his Spanish countrymen and women. The piece is composed in blacks and grays, emulating the tones of newsprint. Of course, as a protest, Guernica has a Didactic agenda: condemning the war crimes of the Fascist forces. Picasso uses deconstructive techniques to portray the agony of people, children, and animals dismembered by war. Some of the distorted heads expand like balloons, perhaps suggesting the accusing ghosts of the victims. That bull in the upper left has been the subject of many interpretations. It is probably safe to suggest deep links with the Spanish people who love their bulls and who have endured repeated invasions and civil wars for thousands of years. All seems to be contained in a single room with a lone light bulb telling the tale of the atrocity.

For many years, Guernica was referred to as the greatest painting of the century. Whether or not we “like” it or would enjoy hanging it in our living rooms, it surely has an impact for the patient, the observant, and the thoughtful.

“The Man with the Blue Guitar”

Wallace Stevens, from “The Man with the Blue Guitar” (1937)

Wallace Stevens, from “The Man with the Blue Guitar” (1937)

I

The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green.

They said, ‘You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.’

The man replied, ‘Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.’

And they said then, ‘But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.

Wallace Stevens wrote deeply reflective poems probing boundaries between subjectivity and “reality.” “Notes toward a Supreme Fiction” (1942), explores mingling imagination, faith, myth, and art. Stevens was fascinated by the way contemporary artists such as Picasso playfully and provocatively manipulated that boundary. Our excerpt from a long poem poses the challenge faced by audiences who on the one hand want art to take them beyond their reality and on the other become frightened and impatient when they lose touch with what they know.

Surrealism

In 1900, Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams. This watershed work challenged people throughout the world to consider levels of the mind other than consciousness. Freud’s notion of the traumwerke—dreamwork—opened psychology and the arts to deep structures of meaning that found expression in the Surrealist movement:

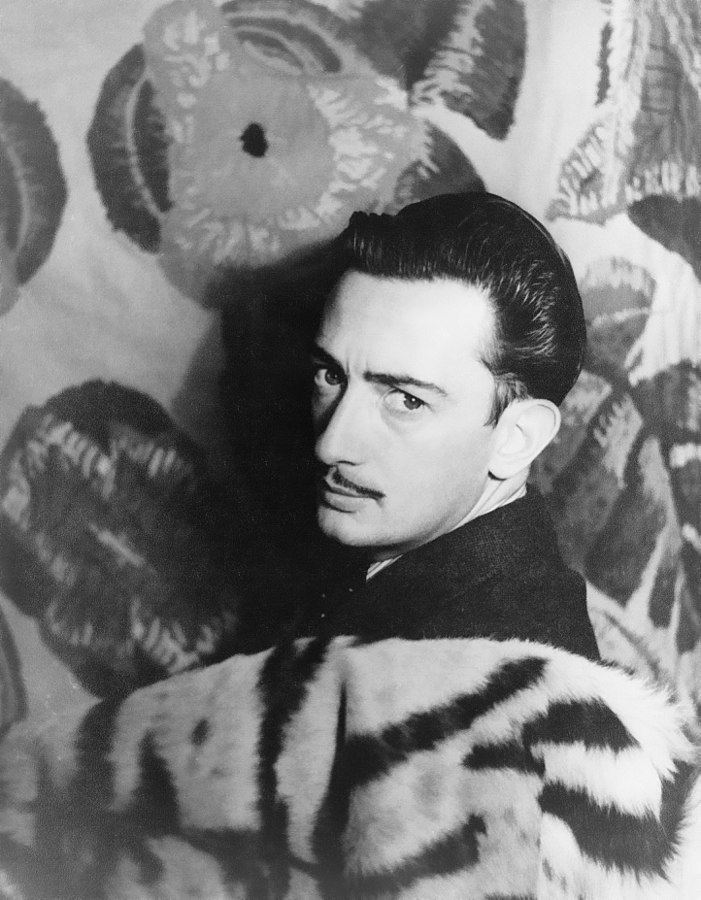

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory rather plainly lays out a land and seascape with conventional perspective. The objects are all recognizable. They are also impossible, warped by the twisting effects of dreams.

|

|

| The Persistence of Memory. (1931). Oil on canvas. | Carl Van Vechten. (1939). Portrait of Salvador Dali. |

So what’s with those drooping clocks? Let your mind play. Clocks, time dreamwork … subjective time. Remember the title: memory with all of its annoying, distorting persistence. Art is no more of a distortion of “reality” than is our all too human remembered fantasy.

By the way, Dali played a role in a major film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. In Spellbound (1941), Gregory Peck’s character undergoes intensive psychoanalysis. Under hypnosis, he experiences a vivid dream vision. We experience that vision in a dream sequence fusing cinematography, animation, and set design, all composed by Salvador Dali.

Bonus video: Dalí, Salvador. (1945). Dream Sequence. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound.

Abstract Art

All of which brings us to the supreme moment of art subverting classical conventions. We’ve seen artists distort and deconstruct the visual subject. In 20th Century Abstract art, artists began to ignore the representation of a visual subject altogether:

The conceptual seeds of abstract art go back as far as Plato, 2,500 years ago (Abstract art). In the Philebus dialogue, Socrates says “I do not mean by beauty of form such beauty as that of animals and pictures…but straight lines and circles, and the plane or solid figures which are formed out of them … for these I affirm to be … eternally and absolutely beautiful.” The 19th Century English painter Joshua Reynolds wrote, “the beauty of form alone… makes of itself a great work, and justly claims our esteem and admiration” (Abstract art).

But what is it supposed to be? Many, many viewers balk at art that represents nothing. If you are skeptical, let me remind you that you enjoy abstract designs in your home every day: Tartan plaids, polka dots, pin stripes, geometrical designs and more in clothing, wallpaper, and furniture coverings. Still, you are free to turn finally away. But I would ask you to at least briefly open yourself to the rich textures of purely formal elements composed in abstract art.

Wassily Kandinski, Pioneer of Abstraction

|

| Wassily Kandinsky. (1925). Yellow, Red, Blue. Oil on canvas. |

The title of Kaninsky’s Yellow, Red, and Blue suggests a purely formal, abstract composition. And indeed the powerful colors exert their spell along with deftly alternated geometrical and organic shapes and lines. However, I’ll bet you can find represented subjects in the composition. Kandinsky pioneered abstract design while including elements of the natural.

Bands of drenching color: Mark Rothko

The canvases for which Mark Rothko is famous follow a predictable abstract formula: horizontal bands of color. Yet many people find his work more accessible than other abstracts.

|

|

| Untitled (Black, Red over Black on Red). (1964).Oil on canvas. | No.5/No.22. (1964). Oil on canvas. |

So what is that brings people to tears in front of pure color and form? In part, surely we respond to the dense, drenching colors, often deep, organic reds. But there is something mesmerizing about those borders, never geometrical, always organic, invariably layered and bleeding. The WikiArt gloss for No. 5/No. 22 explores this visual ambivalence:

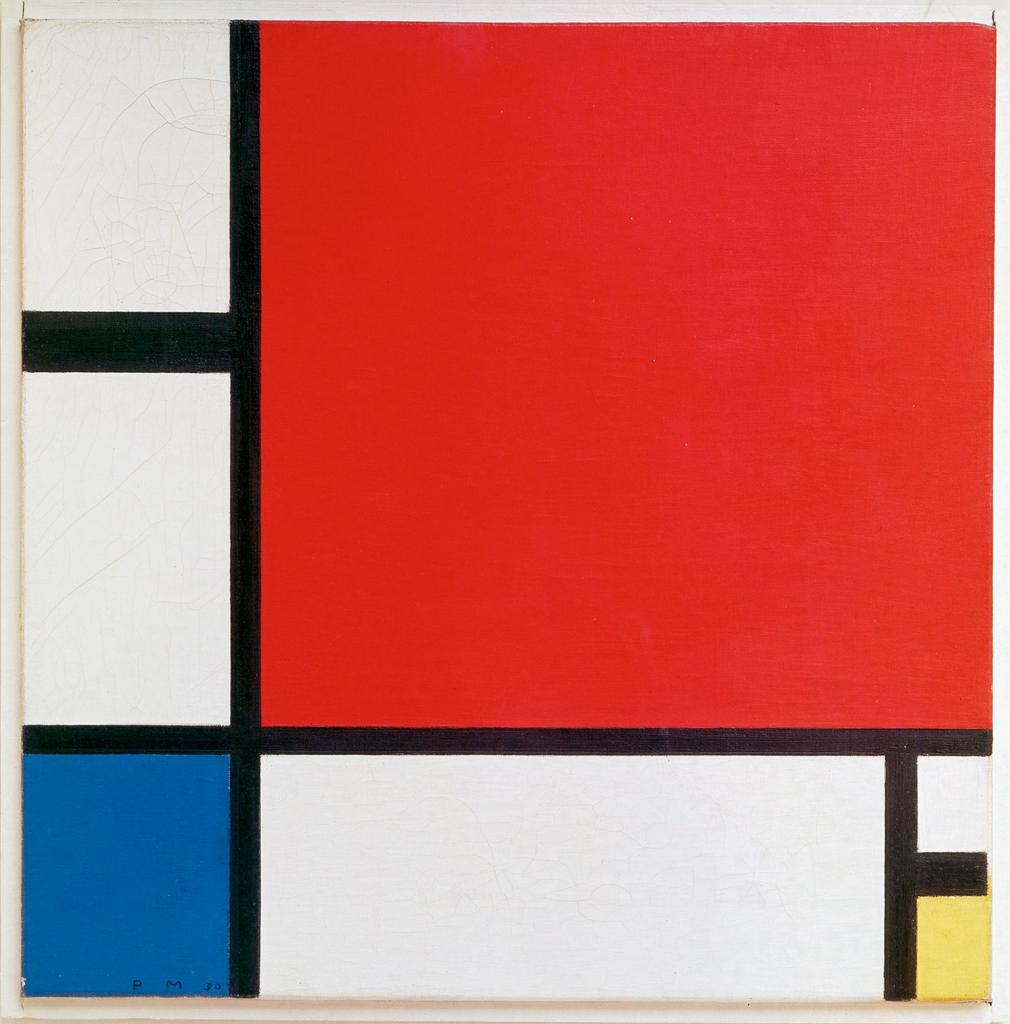

Grids of Eternal Order: Piet Mondrian

Before World War I, the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian painted landscapes and seascapes. Then, in Amsterdam during the war, he began to cultivate a purely formal, abstract style:

|

| Piet Mondrian. (1930): Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow. |

So what do we have here? Lines. Colored rectangles in primary colors. Given a ruler and an elementary paint set, a child could do this, right?

Well, no. The design turns out to be astonishingly complex, an exercise in composition. Look closely at the lines. They vary in width. Some continue to the edge of the canvas. The vertical line on the left does not, allowing the top left rectangle to open out into unbounded space. Dynamic tension between open and closed spaces always enlivens a Mondrian. Notice as well the asymmetrical balance that matches the large red square diagonally to the smaller blue and vertically with the yellow. Exploring a Mondrian is an exercise in analyzing composition.

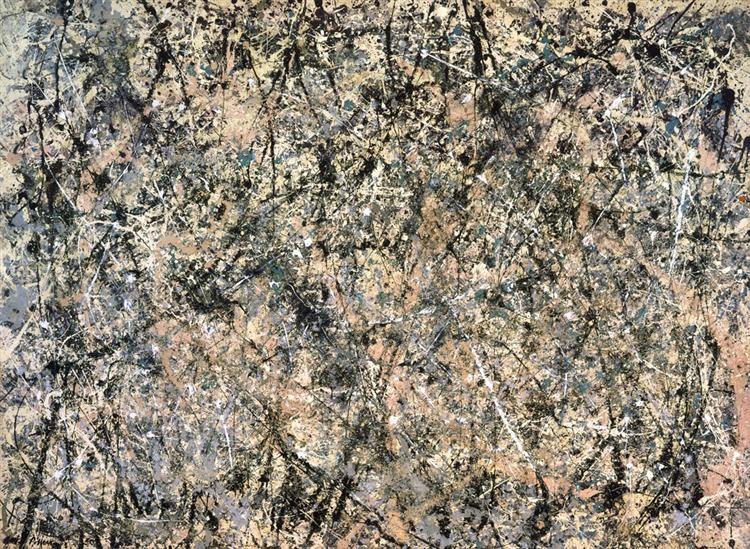

Abstract Expressionism: Jackson Pollock

Perhaps the high-water mark of abstract art emerged in the 1940s—Abstract Expressionism:

The first major development in American art to achieve international status and influence. … The painters embraced by the term and … shared a similarity of outlook rather than of style—a spirit of revolt against tradition and a belief in spontaneous freedom of expression. …

Certain qualities are basic to most Abstract Expressionist painting: … working on a huge scale; emphasis on surface qualities so that the physical reality of the canvas is stressed. … There was a certain unity of fundamental attitudes: the glorification of the act of painting itself; the conviction that abstract painting could convey significant meaning and should not be viewed in formalist terms alone; and a belief in the absolute individuality of the artist (Abstract Expressionism).

One of the avatars of abstract expressionism was Jackson Pollock:

|

|

| Number 1 (Lavender Mist). (1950). Oil, enamel, aluminum canvas | Number 18. (1950). Oil and enamel on Masonite |

Many people are completely put off by the apparent chaos of a Pollock. Anyone can drip paint on a canvas! Yet standing in front of one of Pollock’s numbered painting is a remarkable experience. One is staggered by the density of visual elements. Globs of paint, bits of string and other materials create in his vast canvases a density of texture impossible to convey in a photograph. Not so random lines, arcs, and daubs of paint constellate, rhythmically repeat, and duel for dominance. If one gives oneself up to the sheer experience of paint, canvas, line, light, dark, , color, and especially texture, one can become rapt in a dramatic visual dialogue. We detect no represented subject, but, perhaps because of this, our eyes are absorbed in a stunningly rich encounter.

If you wonder how one could possibly “read” such a painting, explore the O’Connor article on him. O’Connor provides a fascinating analysis of Pollock’s No. 2 that unlocks the intension and design lying within the apparently chaotic visual elements. You may or may not be persuaded, but hopefully you will begin to see that work like this has great depth and richness.

References

Abstract art [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-13.

Abstract expressionism [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-14.

Braque, G. (Autumn 1913). Woman with a Guitar (Femme à la guitare; La joueuse de guitare; La guitariste; Jeune fille à la mandoline). [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée National d’Art Moderne. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_30936255.

Cubism. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-949.

Dalí, S. (1931). The Persistence of Memory. [Painting]. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. ID 79018. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMOMA_10312310520.

Dalí, S. (1945). Dream Sequence. Hitchcock, A. [Dir.]. Spellbound [Film] Selznick International Pictures. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyPe1Jahyfo.

Fauvism. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1238.

“Kagle” Mask. Dan People. (n.d.). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Accession number 2011. 70.2. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/113448/kagle-mask-dan.

Kandinsky, W. (1925). Yellow, Red, Blue [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000983229.

Kandinsky, W. [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-1348.

Le Bateau-Lavoir [Photograph] (c. 1910). Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bateau-Lavoir#/media/File:Le_Bateau-Lavoir,_circa_1910.jpg.

Magritte, R. (1933). The Human Condition [Painting]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_CL_103803515.

Mondrian, P. (1930). Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow. [Painting]. Zürich, Germany: Zürich Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310751326.

Mondrian, P. [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-1804.

No.5/No.22. (2012). [Article]. WickiArt: Visual Art Encyclopedia. https://www.wikiart.org/en/mark-rothko/no-5-no-22.

O’Connor, F. (2011). Pollock, Jackson. In J. Marter (Ed.), The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-1623.

Pende people, Zaire. (N. D.). Mbuya (Sickness) Mask. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001426186.

Picasso, P. (1907). Les Demoiselles d’Avignon [Painting] New York: Museum of Modern Art. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/the-girls-of-avignon-1907.

Picasso, P. (1937). Guernica [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/guernica-1937.

Picasso, P. (1904). La Vie [Painting]. Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/life-1903.

Picasso, P. (1904). The Old Guitar Guitarist [Painting]. Chicago IL: Art Institute of Chicago. Reference number 1926.253. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picasso%27s_Blue_Period.

Picasso, P. (1907). Ma Jolie (Femme a la guitare) [Painting]. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/my-beautiful-woman-with-guitar-1912.

Picasso, P. (1904). Woman Ironing [Painting]. New York, NY: Thannhauser Collection, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Accession 78.2514.41. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/3417.

Picasso, P. (1927). Woman in an armchair [Painting]. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1517/woman-in-an-armchair-pablo-picasso.

Picasso, Pablo. (1907). Ma Jolie (Femme a la guitare) [Painting]. https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/my-beautiful-woman-with-guitar-1912.

Picasso, Pablo [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2739.

Pollock, J. (1950). Number 1 (Lavender Mist) [Painting]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. 1976.37.1. https://www.wikiart.org/en/jackson-pollock/number-1-lavender-mist-1950-1.

Raguenet, J-B. (1763). A View of Paris from the Pont Neuf [Painting]. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Museum, ID 71.PA.26. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/581/jean-baptiste-raguenet-a-view-of-paris-from-the-pont-neuf-french-1763/.

Rothko, M. (1964). No.5/No.22 [Painting] New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.wikiart.org/en/mark-rothko/no-5-no-22.

Rothko, M. (1964). Untitled (Black, Red over Black on Red) [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou. Accession Number AM 2007-126. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_30943855.

Rothko, M. [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-2338?rskey=ptKSEO&result=6.

Stevens, W. (1937). “The Man with the Blue Guitar.” Poetry, Vol. 50, No. 2 (May, 1937), pp. 61-69. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88v/blueguitar.html.

Surrealism. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3405.

Van Vechten, C. (1939). Portrait of Salvador Dali [Photograph]. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LOT 12735. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salvador_Dal%C3%AD_1939.jpg.

associated with Henri Matisse, an early 20th Century movement based on the use of intensely vivid, non-naturalistic colors (Fauvism 2004).

Veduta: in tradition European painting, the Italian word for window designates the omnipresent windows opening onto backgrounds in portraits set in interiors. Check it out: you will be amazed how often, after the 16th Century or so, a windowed landscape doubles the window-like agenda of a European painting.

a genre of painting, drawing, or photograph arranging inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, pottery or furniture, usually in an interior scene.

an early 20th Century, experimental technique of visual composition which deconstructed visual subjects into simple, often geometrical forms viewing the subject from multiple perspectives at once. Form and color are composed in aesthetic arrays minimally connected to the subject.

a quality of art that focuses on impart information, advice, or some doctrine of morality or philosophy.

a movement that drew on Sigmund Freud’s ideas about the creative unconscious to paint with “a scrupulously detailed manner to give a hallucinatory sense of reality to scenes that make no rational sense” (Surrealism).

visual art that makes little or no effort to represent any recognizable subject. Abstract art creates a wholly formal design that appeals to purely aesthetic sensibilities.

images that depict or emulate recognizable objects in a theoretical “real world.” Art is representational even if it distorts the designated object as in stylized or surreal art. The opposite is abstract, or non-figurative, art.

a mid-20th Century movement of painters in America who sought to express powerful themes and emotions on large scale canvases with the textures of the medium: paint, brushstrokes, and added materials such as string. Compositions were wholly abstract, but designed to achieve compositional unity.