Formal Elements of Art

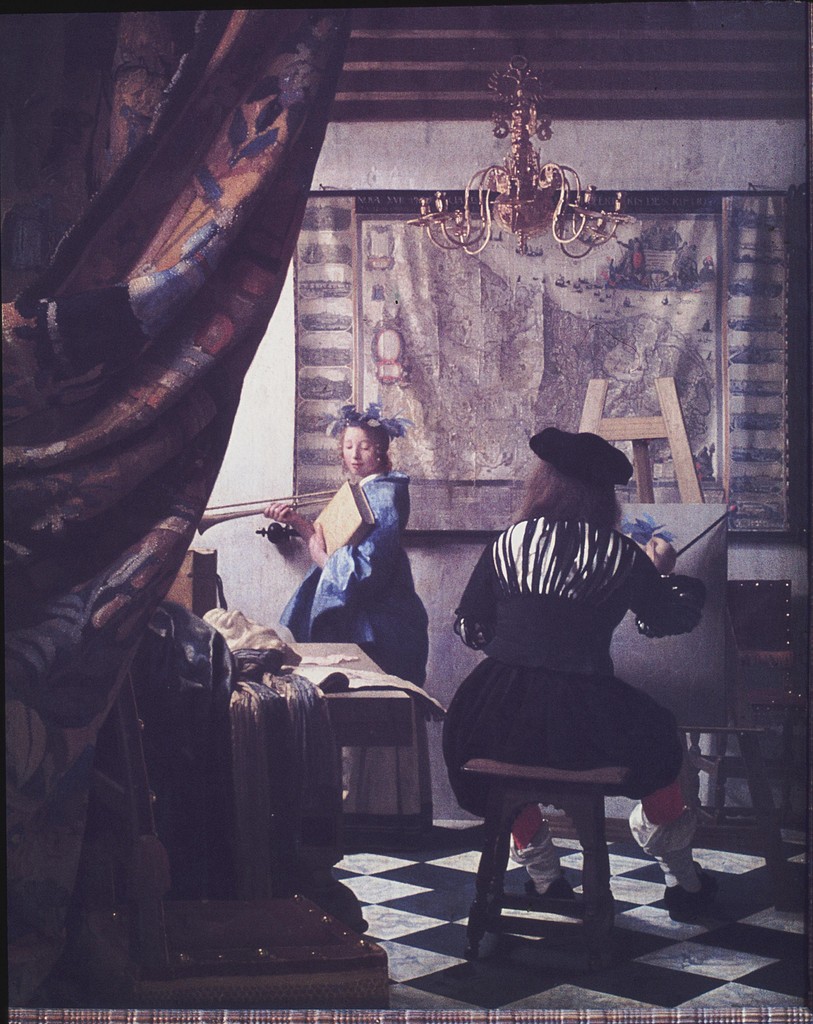

Last week, we explored the Renaissance model of the painting as a window on the world. We illustrated this model with Vermeer’s The Painter and His Model as Klio: the painter at his easel composing his image of a model, all nested within curtained framework of the painting we are viewing. The distance separating us from the painter invites us to reflect on the artist’s viewpoint, his tools and media, his composition, and our own perception.

|

|

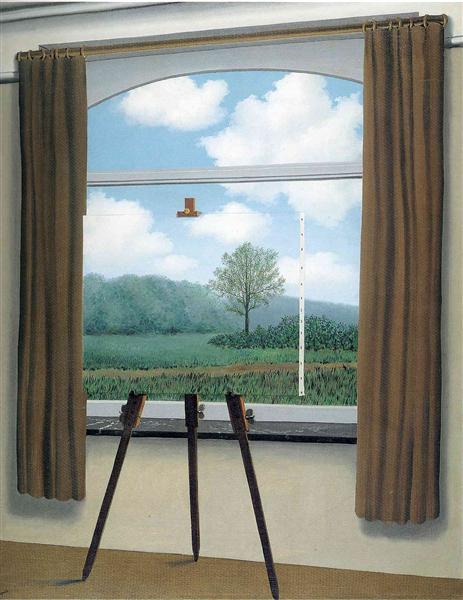

| Jan Vermeer. (1660), The Painter and his Model as Klio. Oil on canvas. | René Magritte. (1933). The Human Condition. Oil on canvas. |

Almost 300 years later, René Magritte toys with this notion of the painting as a window on the world. He paints a window looking out on a landscape. Centered in the pane is a canvas with an apparently, transparent canvas. The image doubles a selected rectangle of the “natural” landscape, just as paintings are supposed to do. The representational technique appears to be straightforward. And yet, we can’t really be sure. Is the tree actually in the landscape or did the painter add it from imagination? The painting raises questions about paintings, and also about The Human Condition. The title invites us to think about the ambiguity of all human perceptions of the world around them. How much do we see and how much do we embellish?

Let’s take a step back and think about the dimensions of this model of painting. Traditional art is Representational. The artifact of the painting produces an image of a visual subject:

In this model, viewers’ attention often focuses on the visual subject: what is it? How realistically is the “real thing” depicted? Often, viewers experience impatience or annoyance when they can’t tell what the subject “is supposed to be” or if they feel the technique is awkward or inaccurate. When we focus on the subject, textures of the medium recede. Paradoxically, we admire the brushwork and pigmentation because they vanish in a rich emulation of the object.

But not all art is representational . We’ve looked at geometrical designs on ancient pottery, arabesques, and architecture with linear designs. People see beauty in such compositions without asking, what is it? Do we critique a paisley shirt if we can’t tell what its designs depict?

Clearly, something besides representation is at play in art. We could turn our attention away from its representational agency and pay attention to the Medium: the canvas, the paint, and the brushstrokes. We could look at color and shape and design as values in themselves. Doing so, we begin to Foreground—to bring to the front of our attention—the formal elements of art.

Formal Elements of Art

We do not need theory to begin to perceive formal elements of images. We do so all the time. “I really love that wallpaper”—the colors, the abstract design. These are formal art elements:

The formal art elements form the basis of the language of art; they consist of eight visual parts: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement.

The following bulleted list condenses definition highlights from Credo articles on formal aspects of art and design.

- Line: one dimensional path of a point through space (article):

- Descriptive lines (drawn): including outlines, contour lines, and hatching lines

- Implied lines (suggested): including edges and lines of sight (the direction in which figures in a composition are looking)

- Direction and movement: generally, verticals, horizontals, and diagonals are directional lines, whereas zigzag and curved lines are movement lines.

- Shape (article): a two-dimensional area defined by a clear border or outline and possessing only height and width

- Form (article): a three-dimensional shape or object. … Form has height, width, and depth, and may be organic, such as a cloud, or geometric, such as a pyramid or cylinder. Organic forms suggest naturalism, while geometric forms convey artificiality.

- Texture (article): surface quality or appearance; how the surface feels or … would feel.

- Movement (article): component of a composition that implies or gives the sensation of activity or action and appear dynamic instead of static

- Optical movement: tricking the eye into seeing movement as used in op art.

- Repetition: using a repeated shape as seen in some cubist works; and

- Suggested movement: relying on the viewer’s knowledge of the subject matter to communicate the idea of movement – for example, a viewer looking at a painting of a car chase will expect the cars to be moving.

- Value (article): the relationship between tones (ranging from light to dark), and the degree of lightness or darkness of a color; … a scale from white to black

- Reflected light: light that bounces off an object making it visible

- Shading: a technique used to make a form look solid

- Chiaroscuro (Italian ‘light–dark’): dramatic contrast of light and dark

- Value as mood or feeling, representing a certain frame of mind or state.

- Color (article): the quality or wavelength of light emitted or reflected from an object.

- Hue: the name of the color achieved by mixing pigments, adding colored elements (as in a mosaic) or the like

- Value, the lightness and darkness of a color

- Saturation (color) or intensity: brightness or dullness of a color

- Complementary colors: hues directly across from each other on the color wheel.

- Warm (yellow, red, orange) versus Cool (violet, green, blue) colors

Obviously, artists achieve these formal elements using media. Color and Value are captured in a mosaic by tesserae and in painting by pigments fixed in oil, tempera, or ink. Texture can be simulated, but also embodied in media and technique: e.g. brushwork leaving daubs of paint and allowing the texture of the canvas to show through.

Composition (visual): Design Principles

Formal elements are furthermore composed—artistically combined— to form a design. Core aspects of design include the following (Design Principles):

- Unity: the “wholeness” of composition, … parts working together creating one total picture – a seamless composition

- Proximity or putting objects close to one another in the composition: … When objects are placed close together the viewer’s eye is forced to move from one object to the next inevitably taking in the entire composition

- Similarity: making things similar, also creates a sense of wholeness. Using similar textures, colors, or shapes tends to visually connect the parts of a composition.

- Continuation: when vision is directed by a line (actual or implied) that travels around the composition.

- Variety and harmony: variety pertains to differences and diversity. … Harmony in art, as in music, is the agreeable blending of elements … in a perfect balance.

- Emphasis (or dominance): the focal point of a composition, … highlighting an element in order to control the viewer’s eye and stress significance of objects.

- Lines of sight: eyelines of figures in the work drawing our eyes to a subject

- Central location in a composition

- Rhythm and movement: repeating an element creates a sense of movement, flow, or activity. In art, rhythm can be felt as well as seen.

- Repetition of the same element or of multiple elements in a type of pattern, [1]

- Progressive repetition of an element, very small to very large; dark to light.

- Balance: equal distribution of visual weight or the placement of elements evenly.

- Asymmetrical balance: balance of different elements, objects, or figures with equal visual weights: e.g. large open space balancing heavy, perhaps dark zones

- Symmetrical balance: balance of the same elements on both sides of an implied central vertical or horizontal axis.

Whew! That’s some list. No, you are not being asked to memorize it. Yet a few moments on these pages can sensitize your awareness of the artistry at work in artistic composition.

[1] Does this notion of repeating a form in a pattern sound familiar? It should. It is the equivalent of scheme figures of speech in poetry and oratory: parallelism, anaphora, etc.

References

Academic art [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1816.

Ingres, J. A. D. (c. 1812). Napoleon Bonaparte receiving the keys of Vienna at the Schloss Schönbrunn, 13th November. [Painting]. France: Château de Versailles. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Napoleon_en_de_sleutels_van_wenen.jpg.

Art elements [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/art_elements/0?institutionId=712.

David, J-L. (1784). The Oath of the Horatii [Painting]. Paris: muse du Louvre, ID ART147619. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARMNIG_10313257933.

Design principle [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/design_principle/0?institutionId=712.

Form [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/form/4.

Line [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/line/0.

Design principle [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/design_principle/0?institutionId=712.

Form [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/form/4.

Movement [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/movement/1.

Raphael (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2890.

Shape [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/shape/2.

Texture [Article]. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/content/entry/heliconhe/texture/1.

Vermeer, J. (1665-1666). The Painter and his Model as Klio [Painting]. Vienna, Austria: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490406.

a characteristic of art in which the image depicts or emulates recognizable objects in a theoretical “real world.” Art is representational even if it distorts the designated object as in stylized or surreal art. The opposite is abstract, or non-figurative, art.

images that depict or emulate recognizable objects in a theoretical “real world.” Art is representational even if it distorts the designated object as in stylized or surreal art. The opposite is abstract, or non-figurative, art.

a European, not an Arabic, word for a distinctive kind of vegetal ornament that flourished in Islamic art from the 10th to the 15th century. Sometimes applied to winding and twining vegetal decoration in many arts and to meandering themes in music (Arabesque).

A term used to describe both the various methods and materials used by artists. For example, painting, drawing, and sculpture are three different media, and bronze and marble are two of the media of sculpture. More spe-cifically, ‘medium’ also refers to the liquid in which pigment is suspended in any kind of painting, for example linseed oil is the most commonly used medium in oil paint (Medium).

A) In visual art, the elements at the front of the field of composition and B) in general, the technique of drawing attention to a particular element of art.

the elements that form the basis of the language of art irrespective of any subject that may or may not be represented: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement.

in visual art, a one dimensional path of a point through space (article). Line may directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

in visual art, a two-dimensional area defined by a clear border or outline and possessing only height and width.

in visual art, a three-dimensional shape or object with height, width, and depth

in visual art, an irregular form such as a cloud or rocky terrain that suggests natural origin (article).

in visual art, a form composed of precise, smooth lines, shapes, and forms such as pyramids or cylinders suggesting human artifice.

in visual art, the artifact’s surface quality or appearance; how the surface feels or would feel.

in visual art, an illusion of how a represented object would feel if it were real and could be touched (article). E.g. painting technique suggesting the feel of wood grain, fabrics, water, or the like.

in visual art, the textures of the painting, sculpture, mosaic, or textile. E.g., in a painting, the grain of the canvas, the marks of brushwork in the paint, or embedded materials—string, sand, etc.

in stationary visual art, a component of a composition that implies or gives the sensation of activity or action and appear dynamic instead of static.

in visual art, the movement of the viewer’s eyes in response to composition and suggestion: e.g. the viewer’s eyes following the eye lines of characters in the image.

in visual art, the suggestion of movement in the frame based on the viewer’s knowledge. E.g. a viewer looking at a painting of a car chase will expect the cars to be moving.

the relationship between tones (ranging from light to dark), and the degree of lightness or darkness of a color; … a scale from white to black.

a term used to describe the effects of light and dark in a work of art, particularly when they are strongly contrasting (Chiaroscuro). Associated with Baroque painting, but common in the art of the early 20th Century: e.g. German expressionism and film noir cinema.

the quality or wavelength of light emitted or reflected from an object (article). Components of color include Hue, Value, Saturation (intensity) and Color Temperature.

the name of a specific color achieved by blending primary colors through mixing pigments or by adding colored elements as in a mosaic.

the brightness or dullness of a color based on the intensity of the pigment.

hues directly across from each other on the color wheel which create an enhanced aesthetic resonance: e.g. red and green, yellow and violet.

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, Variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance.

the “wholeness” of composition, parts working together creating one total picture – a seamless composition.

Implied lines of perception emerging from the eyelines of characters within a work of art. Subtle techniques by which artists organize viewers’ experience of a painting or photograph.

in visual art, a sense of movement arising from repeated elements in the composition.

in visual art, the distribution of visual weight or placement of elements.

balance of different elements, objects, or figures with equal visual weights: e.g. large open space balancing heavy, perhaps dark zones

in visual art, balance of the same elements on both sides of an implied central vertical or horizontal axis.