Harlem: Prophetic Voices

Whitman sings the freedom of the thousands who spread across the Continent in a frontier that receded until it hit the Pacific. But what of those who were displaced? What of the slaves whose skin was branded with perpetual shame?…

As we see in Amos, prophetic voices often arise from minority, marginalized people. In the late 19th Century, African Americans throughout the South began to vote with their feet against the brutalities of “Jim Crow” segregation. Thousands moved to the industrial cities of the North where they could get better work and somewhat less restriction on their way of life. Many ended up In Harlem, New York City. The term Harlem Renaissance refers to a …

|

| Winold Reiss. W. (c.1925). Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I. Ink on paper. |

Artists and writers of the Harlem Renaissance faced a daunting dilemma. The racial myths supporting slavery insisted that African Americans were inferior, sub-human beings who were incapable of “classical” cultural achievements. A small but vital middle class, however, sent its children to traditionally Black colleges to prepare for professional careers such as medicine and law. Scholars like W.E.B. DuBois and James Wheldon Johnson began to publish the work of writers who demonstrated to the world that Black artists could be just as skillful and accomplished as white counterparts. African Americans determined to “advance the race” diligently sought to shake off all traces of slavery.

But how do you prove to white audiences that “you are just as good” as sophisticated White writers? Everyone, including those who sponsored African American artists, assumed that the highest culture expressed itself in the “superior” White, Anglo-American voice. Certainly, the first step in achieving elegance would be to radically eliminate the voice of the ex-slave. One couldn’t be a great poet writing in the voice of the “street Negro” (to use the term of the day), could one?

W.E.B. DuBois was proud of Countee Cullen, the black poet so capable that a sample of his verse was once thought by literary scholars to be that of an English master. And Cullen was a superb poet who had as much right to compose in literary English as anyone else. But Cullen paid a price for being conventionally literary. He had to abandon the dialect in which his people spoke. Two writers refused to sacrifice their people’s voices to literary ambition. These writers were often criticized by African American intellectuals for honoring in their writing the voices which seemed to many to confirm stereotypes of Black inferiority.

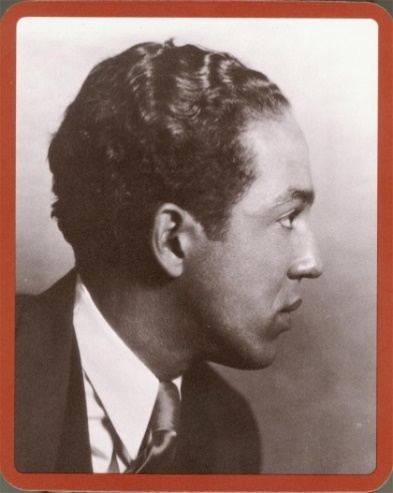

Langston Hughes

|

| Allen, James L. (1930). Langston Hughes Photograph. |

Langston Hughes embodied the complex American history of race. His father was descended from black great-grandmothers and white, slave owning great-grandfathers.

By the mid-1920s, Hughes had become one of the most celebrated young members of the artist community in Harlem. But Hughes was frustrated by the tendency of older sponsors like W.E.B. DuBois and Alain Locke to push Black artists to emulate the mainstream (White) elite. In 1925, Hughes expressed his frustration at the dilemma facing Black artists in a prophetic essay.

from Langston Hughes, “The Negroi Artist and the Racial Mountain”

Like Cullen, Hughes was capable of writing verse in any voice. Unlike Cullen, he chose the voice that rolled richly through Harlem streets and juke joints. This was a time when Black blues and jazz musicians were gaining a wide audience through radio, records, and performances at Harlem clubs. Jazz and blues musicians were often criticized for styles dismissed as “primitive.” But Hughes was proud of his people’s music. He entitled his first collection of poetry The Weary Blues (1926) and proved that its rhythms could lead to superb poetry. In Week 2, we explored the structure of a blues: three repetitive lines followed by a resolving line. As you can see and hear, Hughes emulated that blues pattern here.

Droning syncopated[1] tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue[2] the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway. . . .

He did a lazy sway. . . .

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano moan with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy[3] tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man’s soul.

O Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan—

“Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine[4] to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more—

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.

[1] Syncopated: in music, a rhythm with a stress on the off beat: ta-Da, ta-DA, ta-Da. A heavy emphasis on syncopation is one of the hallmarks of jazz.

[2] Lenox Avenue: one of the principal streets in Harlem, New York.

[3] Raggy: a reference to the African American jazz tradition, one of the earliest genres of which was the Rag, a composition in syncopated Rag Time.

[4] Gwine: that is, I am going to …

A poem emulating Blues will certainly display rhythm. But what sort? You’ll notice Rhyme and also Metrical patterns. But they keep shifting freely, liberated from strict obedience to the rules of traditional English verse forms. Actually, most of Hughes work, including “Mother to Son” (Week 1), are written in Free Verse influenced by the Bible and Whitman. In this next poem, Hughes digs deeply into his ancestral roots, woven together by the courses of the great rivers of the world.

Langston Hughes (1926). “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Read this poem thoughtfully, sensitive to its themes, images, and rhythms. Listen to the audio phile below. You have the tools to process the figures of speech: metaphors, anaphora, parallelism, catalogue (Stanza 3).

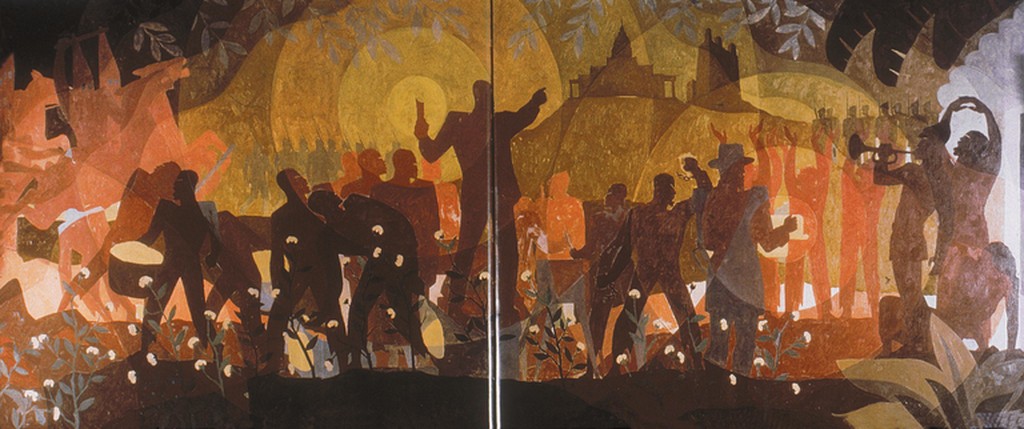

Aaron Douglas: Aspects of Negro Life

Today, the Harlem Renaissance is mostly remembered for its writers. But African American painters and sculptors also flourished in a rare moment of sponsorship by mainstream wealth. In 1934, Aaron Douglas painted a series of four oils representing key eras in the history of a people. These oils are currently held in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library.

- Panel 1: The Negro in an African Setting. The 1st panel looks in on African people celebrating their culture, its music, its art, and its warrior pride. Notice the layered technique: flattened profiles defining zones of depth without perspective. And don’t miss the haloes and shafts of light that organize the composition, centering on the cultural figurine.

- Panel 2: From Slavery Through Reconstruction. The 2nd panel reviews the long years of slavery, often in cotton fields, and the Union troops breaking its chains. Haloes of light focus our eyes on the Emancipation Proclamation held by a Frederick Douglas-like character looking to the Federal Congress that banned slavery in the 13th Amendment.

|

|

|

|

- Panel 3: an Idyll of the Deep South. An idyll normally celebrates rural life, and we see African Americans, freed from slavery, gathered to sing their culture. To the right we see hard labor in the fields, the only work permitted them. In the background, ghostly figures suggest lynch mobs and Jim Crow oppression. Piercing the image and its layers of light is a single ray emanating from a star and offering faith and hope.

- Panel 4: Song of the Towers. Again, light focuses our vision. Haloes surround the Statue of Liberty and a saxophone that celebrates the jazz music that was just beginning to earn some respect for Black culture. In the bottom corners, a man trapped in the Deep South dreams of liberty and another follows the Great Migration to the industrial cities of the North and the towers of Manhattan. But don’t miss the ghostly hands of mainstream culture clawing back on those reaching for freedom.

The Glorious African American Voice: Zora Neal Hurston

I was glad when somebody told me, “You may go and collect Negro folklore” (Mules and Men).[5]

[5] Compare Psalm 122.1: I was glad when they said unto me, Let us go into the house of the Lord.

Born in 1891, Zora Neal Hurston grew up in the small town of Eatonville, Florida. Though she traveled far, she never really left. As James Joyce wrote in exile of Dublin, Hurston always wrote of Eatonville. Hurston recognized that the legacy of Eatonville was unique

|

| Zora Neal Hurston. (1935-1943). [Photograph]. |

In the late 19th Century, Eatonville Florida was a wholly African American town. Let me repeat that. No one who lived in Eatonville wasn’t Black. While its residents mostly worked for White employers in the surrounding towns, the residents of the town had achieved an autonomy unheard of in Jim Crow America. They had a mayor, their own shops, and even, as we learn in a memorable scene from Their Eyes Were Watching God, a street light! On the first page of this great novel—if only we had time to read it!—Hurston captures the liberating moment when servants return home from serving masters and mistresses:

from Chapter 1, Their Eyes Were Watching God

Growing up in Eatonville, Hurston had a firm conviction of the worth of her own people. Her journey to Harlem was a long one but, in 1925, she enrolled in Barnard College, Columbia University. As a Masters Degree candidate in anthropology she was required to compile an ethnography of a cultural group. She asked her mentor, the famed anthropologist Franz Boas, for permission to return to Eatonville and study her home town. “I was glad when somebody told me, “You may go and collect Negro folklore” (Mules and Men).

Hurston’s glee at the blessing of senior faculty for her return to her hometown was far more than nostalgia. At that time, virtually the entire educated world, including many of the members of the Harlem Renaissance community, considered African American English to be a primitive, error-ridden version of the “real thing.” Hurston did not.

In Eatonville, Hurston transcribed tape recordings of front porch conversations which she later incorporated into her fiction. These “lying sessions” were serious business. In a memorable scene from Their Eyes Were Watching God, locals gather on the porch of the community store. “Playin’ de dozens,” they compete with each other in ritual insults and outlandish tales.

from Chapter 6, Their Eyes Were Watching God

Sometimes Sam Watson and Lige[6] Moss forced a belly laugh … with their eternal arguments. It never ended because there was no end to reach. It was a contest in hyperbole and carried on for no other reason. Sam would be sitting on the porch when Lige walked up- If nobody was there to speak of, nothing happened- But if the town was there like on Saturday night, Lige would come up with a very grave air- Couldn’t even pass the time of day, for being so busy thinking- Then he’d say,

“Dis question done ’bout drove me crazy. And Sam, he know so much into things, Ah wants some information on de subject.” …

Sam begins an elaborate show of avoiding the struggle. That draws everybody on the porch into it. “How come you want me tuh tell yuh? You always claim God done met you round de corner and talked His business wid yuh. ‘Tain’t no use in you askin’ me nothin. Ah’m questionizin’ you.”

“How you goin tuh do dat, Sam? Ah arrived dis conversation mahself? Ah’m askin you!”

“Askin’ me what? You ain’t told de subjick yit-”

… By this time, they are the center of the world.

“Well all right then. Since you own up you ain’t smart enough tuh find out whut Ah’m talkin’ ‘bout Ah’ll tell you- Whut is it dat keeps uh man from gettin’ burnt on uh red-hot stove — caution or nature?”

“Shucks! Ah thought you had somethin’ hard tuh ast me. Walter kin tell yuh dat-”

“If de conversation is too deep for yuh, how come yuh don’t tell me so, and hush up? …Ah’m uh educated man, Ah keeps mah arrangements in mah hands.” …

“And then agin, Lige, Ah’m gointuh tell yuh- Ah’m gointuh run dis conversation from uh gnat heel to uh lice- It’s nature dat keeps uh man off of uh red-hot stove-”

“Uuh huuh! Ah knowed you would going tuh crawl up in dat holler![7] But Ah aims tuh smoke yuh right out- ‘Tain’t no nature at all, it’s caution, Sam.”

“’Tain’t no sich uh thing! Nature tells yuh not tuh fool wid no red-hot stove, and you don’t do it neither-”

“Listen’ Sam, if it was nature, nobody wouldn’t have tuh look out for babies touchin’ stoves, would they? ‘Cause dey just naturally wouldn’t touch it- But dey sho will- So it’s caution.”

“Naw it ain’t, it’s nature, cause nature makes caution. It’s de strongest thing dat God ever made, now. Fact is it’s de onliest thing God ever made. He made nature and nature made everything else.”

“Naw nature didn’t neither. A whole heap of things ain’t even been made yit”

“Tell me somethin’ you know of dat nature ain’t made.”

“She ain’t made it so you kin ride uh butt-hcaded cow and hold on tuh de horns.”

“Yeah, but dat ain’t yo’ point.”

“Yeah it is too.”

“Naw it ain’t neither.”

“Well what is mah point?”

“You ain’t got none, so far. … [You] know mighty much, but [you] ain’t proved it yit. Sam, Ah say it’s caution, not nature dat keeps folks off uh red-hot stove.”

“How is de son gointuh be before his paw? Nature is de first of everything. Ever since self was self, nature been keepin’ folks off of red-hot stoves. Dat caution you talkin’ ’bout ain’t nothin’ but uh humbug. He’s uh inseck dat nothin’ he got belongs to him. He got eyes, lak somethin’ else; wings lak somethin’ else —everything! Even his hum is de sound of somebody else.”

“Man, whut you talkin’ ’bout? Caution is de greatest thing in de world.” …

“Show me somethin’ dat caution ever made! Look whut nature took and done. … Now you tell me, how come, whut got intuh man dat he got tuh have hair round his mouth? Nature!”

The porch was boiling now. …

“Look at dat great big ok scoundrel-beast up dere at Hall’s fillin’ station — uh great big old scoundrel. He eats up all de folks outa de house and den eat de house.”[8]

“Aw ’tain’t no sich a varmint nowhere dat kin eat no house! Dat’s uh lie. Ah wuz dere yiste’ddy and Ah ain’t seen nothin’ lak dat. Where is he?”

“Ah didn’t see him but Ah reckon he is in dc back-yard some place. But dey got his picture out front dere. They was nailin’ it up when Ah come pass dere dis evenin’.”

“Well all right now, if he eats up houses how come he don’t eat up de fillin’ station?”

“Dat’s ’cause dey got him tied up so he can’t. Dey got uh great big picture tellin’ how many gallons of dat Sinclair high-compression gas he drink at one time and he’s more’n uh million years old.”

“’Tain’t nothin’ no million years old! … How dey goin’ to tell he’s uh million years old? Nobody wasn’t born dat fur back.”

“By de rings on his tail Ah reckon. Man, dese white folks got ways for tellin’ anything dey wants tuh know.”

“Well, where he been at all dis time, then?”

“Dey caught him over dere in Egypt. Seem lak he used tuh hang round dere and eat up dem Pharaohs’ tombstones. Dey got dc picture of him doin’ it. Nature is high in uh varmint lak dat. Nature and salt. Dat’s whut makes up strong man lak Big John de Conquer He was uh man wid salt in him. He could give uh flavor to anything”

“Yeah, but he was uh man dat wuz more’n man. Tain’t no mo’ lak him. He wouldn’t dig potatoes and he wouldn’t rake hay. He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away.”

“Oh yeah, somebody else could if dey tried hard enough- Me mahself, Ah got salt in me. …

“Lawd, Ah loves to talk about Big John. Less we tell lies on Ole John.”

[6] Lige: short for Elijah.

[7] Holler: i.e. a hollow, or low area in the landscape in which an animal might hide.

[8] The signs at Sinclair gasoline stations used to feature the stylized profile of a dinosaur. See an example: link.

Do you find this hard to read? Lots of misspelled words and poor grammar, right? Except that Hurston, a trained anthropologist, is transcribing actual speech. And the grammar is perfectly correct according to the syntax of a dialect quite different from standard, edited English. Hurston treated the tongue of her people as an actual language, and decades later linguists and educators began to understand that she was correct. African American English has its own rules and patterns. Historically, when white authors have attempted to parody it–for example Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus stories–they have invariably gotten those patterns wrong. Hurston is striving to get them right.

Her care for authenticity arises from her love of the Genre. Hurston knows that “playin’ de dozens,” the verbal jousting of a people whose language is dismissed as “primitive,” actually pulses with devastating wit and eloquence. Talented jesters earn a reputation that, in a time before radio or television, gathers the town to listen to the fun. Sam and Lige (i.e. Elijah) face off in “a contest in hyperbole and carried on for no other reason,” each vying for the biggest laugh and the crowd’s assent. In this case, they are exploring the nature versus nurture debate that scholars today still wrestle with. Their sham debates are studded with witticisms:

- Ah’m gointuh run dis conversation from uh gnat heel to uh lice (head to toe)

- She ain’t made it so you kin ride uh butt-headed cow and hold on tuh de horns

- Ah knowed you was going tuh crawl up in dat holler! (i.e. hollow, a small valley)

- He wouldn’t dig potatoes and he wouldn’t rake hay. He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away.

“He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away”—whom does that describe? A heroic slave who is able stand up to a brutal institution. There is a brief mention here of Big John de Conquer, a standard character in many African American folk tales, several collected by Hurston. Big John is a noble slave who, like mythic heroes in many cultures, embodies the virtues and courage of a subdued people. The very mention of a hero who could rise above oppression interrupts the sham debate among brilliant men who must every day submit to white masters: “Lawd, Ah loves to talk about Big John. Less we tell lies on Ole John.”

The direct result of Hurston’s anthropological study was Mules and Men, a collection of her transcriptions of oral narrative and African American folk lore. In this collection, we find a range of stories told by a people struggling to survive slavery. As in all mythic systems, certain characters recur: Ol Massa (the white master of the plantation), Big John, de debbil[4]), and personifications of the people. The text teems with “origin stories” that explain how things got to be what they are. In this tale, Mathilda vies with the best male story tellers to explain how, in the long run, women got the best of men.

From Chapter 2, Mules and Men

Said Shoo-pie. “Don’t you know you can’t git de best of no woman in de talkin’ game? Her tongue is all de weapon a woman got,”

George Thomas chided Gene. “She could have had mo’ sense, but she told God no, she’d ruther take it out in hips. So God give her her ruthers. She got plenty hips, plenty mouf and no brains. “

“Oh, yes, womens is got sense too,” Mathilda Moseley jumped in. “But they got too much sense to go ’round braggin’ about it like y’all do. De lady people always got de advantage of mens because God fixed it dat way.”

“Whut ole black advantage is y’all got?” Moseley asked, indignantly. “We got all de strength and all de law and all de money and you can’t git a thing but whut we jes’ take pity on you and give you.”

”And dat’s jus’ de point,” said Mathilda triumphantly, “You do give it to us, but how come you do it?” And … Mathilda began to tell why women always take advantage of men.

You see in de very first days, God made a man and a woman and put ‘em in a house together to live. ‘Way back in them days de woman was just as strong as de man and both of ’em did de same things. They useter get to fussin ’bout who gointer do this and that and sometime they’d fight, but they was even balanced and neither one could whip de other one.

One day de man said to hisself, “B’lieve Ah’m gointer go see God and ast Him for a li’l mo’ strength so Ah kin whip dis ‘oman and make her mind. Ah’m tired of de wa things is.” So he went on up to God. “Good mawnin’, Ole Father.”

“Howdy man. Whut you doin’ ’round my throne so so dis mawnin’?”

“Ah’m troubled in mind, and nobody can’t ease mah spirit ‘ceptin’ you.”

God said: “Put yo’ plea in de right form and Ah’ll hear and answer.”

“Ole Maker, wid de mawnin’ stars glitterin’ in yo’ shin crown, wid de dust from yo’ footsteps makin’ worlds upon worlds, wid de blazin’ bird we call de sun flyin’ out of you right hand in de mawnin’ and consumin’ all day de flesh and blood of stump-black darkness, and comes flyin’ home every evenin to rest on yo’ left hand, and never once in yo’ eternal years, mistook de left hand for de right,[9] Ah ast you please to give me mo’ strength than dat woman you give me, so Ah kin make her mind. Ah know you don’t want to be always comin’ down way past de moon and stars to be straightenin’ her out and its got to be done. So giv me a li’l mo’ strength, Ole Maker and Ah’ll do it.”

“All right, Man, you got mo’ strength than woman.”

So de man run all de way down de stairs from Heben. He was so anxious to try his strength on de woman dat he couldn’t take his time. Soon’s he got in de house he hollered “Woman! Here’s yo’ boss. God done tole me to handle you which ever way.”

De woman flew to fightin’ ‘im right off. She fought ‘im frightenin’ but he beat her. She got her wind and tried ‘im agin but he whipped her agin. She got herself together and made de third try on him vigorous but he beat her every time. He was so proud he could whip ‘er at last, dat he just crowed over her and made her do a lot of things. He told her, “Long as you obey me, Ah’ll be good to yuh, but every time yuh rear up Ah’m gointer put plenty wood on yo’ back and plenty water in yo’ eyes.

De woman was so mad she went straight up to Heben and stood befo’ de Lawd. She didn’t waste no words. She said, “Lawd, Ah come befo’ you mighty mad t’day. Ah want back my strength and power Ah useter have.”

“Woman, you got de same power you had since de beginnin’.”

”Why is it then, dat de man kin beat me now and he useter couldn’t do it?”

”He got mo’ strength than he useter have, He come and ast me for it and Ah give it to ‘im. Ah gives to them that ast, and you ain’t never ast me for no mo’ power.”

”Please suh, God, Ah’m astin’ you for it now. Jus’ gimme de same as you give him.”

God shook his head. “It’s too late now, woman. Whut Ah give, Ah never take back. Ah give him mo’ strength than you and no matter how much Ah give you, he’ll have mo.

De woman was so mad she wheeled around and went on off. She went straight to de devil[10] and told him what had happened.

He said, “Don’t be disincouraged, woman. You listen to me and you’ll come out mo’ than conqueror. Take dem frowns out yo’ face and turn round and go fight on back to Heben and ast God to give you dat bunch of keys hangin’ by de mantel-piece. Then you bring ’em and Ah’ll show you what to do wid ’em.”

So de woman climbed back up to Heben agin. She was mighty tired but she was more out-done than she was tired so she climbed all night long and got back up to Heben. When she got to heaven butter wouldn’t melt in her mouf.

“0 Lawd and Master of de rainbow, Ah know yo’ power. You never make two mountains without you put a valley in between. Ah know you kin hit a straight lick wid a crooked stick.”

”Ast for whut you want, woman.”

”God, gimme dat bunch of keys hangin’ by yo’ mantel.”

“Take em.”

So de woman took de keys and hurried on back to de devil wid ’em. There was three keys on de bunch. Devil say, “See dese three keys? They got mo’ power in ’em than all de strength de man kin ever git if you handle ’em right.

Now dis first big key is to de do’ of de kitchen, and you know a man always favors his stomach. Dis second one is de key to de bedroom and he don’t like to be shut out from dat neither and dis last key is de key to de cradle and he don’t want to be cut off from his generations. So now you take dese keys and go lock up everything and wait till he come to you. Then don’t you unlock nothin’ until he use his strength for yo’ benefit and yo’ desires.”

De woman thanked ‘im and tole ‘im, “If it wasn’t for you, Lawd knows whut us po’ women folks would do.”

She started off but de devil halted her. “Jus’ one mo’ thing: don’t go home braggin’ ’bout yo’ keys. Jus’ lock up everything and say nothin’ until you git asked. And then don’t talk too much.”

De woman went on home and did like de devil tole her. When de man come home from work she was settin’ on de porch singin’ some song ’bout “Peck on de wood make de bed go good.”

When de man found de three doors fastened what useter stand wide open he swelled up like pine lumber after a rain. First thing he tried to break in cause he figgered his strength would overcome all obstacles. When he saw he couldn’t do it, he ast de woman, “Who locked dis do’?”

She tole ‘im, “Me.”

”Where did you git de key from?”

“God give it to me.

He run up to God and said, “Woman got me locked ‘way from my vittles, my bed and my generations. She say you give her the keys.”

God said, “I did, Man, Ah give her de keys, but de devil showed her how to use ’em!”

“Well, Ole Maker, please gimme some keys jus’ lak ’em so she can’t git de full control.”

“No, Man, what Ah give Ah give. Woman got de key.”

“How kin Ah know ’bout my generations.

“Ast de woman.”

So de man come on back and submitted hisself to de woman and she opened de doors. He wasn’t satisfied but he had to give in. ‘Way after while he said to de woman, “Le’s us divide up. Ah’ll give you half of my strength if you lemme hold de keys.”

De woman thought dat over so de devil popped and tol her, “Tell ‘im, naw. Let ‘im keep his strength and you keep y’ keys.”

So de woman wouldn’t trade wid ‘im and de man had to mortgage his strength to her to live. And dat’s why de man makes and de woman takes. You men is still braggin’ ’bout yo’ strength and de women is sittin’ on de keys and lettin’ you blow off till she git ready to put de bridle on you.

[9] How is this as a parody of the catalogues of praise one might find in a sermon or psalm?

[10] de devil: i.e. the Devil, a stock character in African American myth. This character is really more of a trickster God than an incarnation of the Christian concept of Satan. In these tales, de debbil often helps characters by providing a clever solution to a threatening situation.

Cultures evolve myths to help their people navigate their environment. African American myth projected a facsimile world in which, as in reality, servitude is inescapable, but wit provides a refuge in dignity, grace and humor. In the stories, Ol Massa loses his punch and the Woman manages to rise above her double servitude of race and gender. In Eatonville, everyone was a servant, but on that front porch, story tellers competed in fantasy heroics, trading insults and making grandiose claims. Rivals “playin’ de dozens” forged a tradition that eventually led to the global triumph of rap and hip hop.

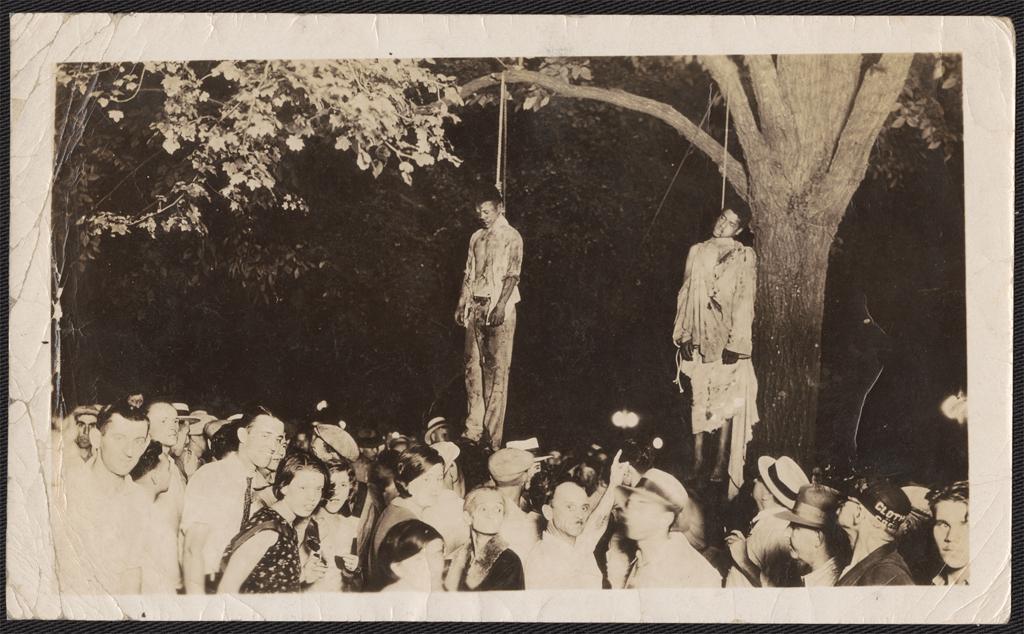

Lady Day’s Strange Fruit

|

| William P. Gottlieb (February 1947). Billie Holiday at the Downbeat Jazz Club. |

Holiday, nicknamed “Lady Day” by saxophonist Lester Young, was known first in Harlem jazz clubs. Her musicianship transformed such standards as “Lover Man,” “These Foolish Things,” and “Embraceable You” into masterpieces. She was also a tough woman not afraid to fight boors and racists. In the late 1930s, the promise of the Harlem Renaissance had given way to the Depression and continued oppression of African Americans. Lynchings were common, ignored by the mainstream and remembered only by Black newspapers and journals such as Crisis, the publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In 1939, Lady Day saw a way to resist.

“Strange Fruit” is a song performed most famously by Billie Holiday, who first sang and recorded it in 1939. Written by a white, Jewish high school teacher from the Bronx and a member of the Communist Party, Abel Meeropol wrote it as a protest poem, exposing American racism, particularly the lynching of African Americans. Such lynchings had occurred chiefly in the South but also in other regions of the United States. Meeropol set it to music and with his wife and the singer Laura Duncan, performed it as a protest song in New York venues (Strange Fruit).

|

| Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. (1930). Gelatin silver prints. |

Abel Meeropol. (1929): “Strange Fruit”

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

References

Allen, James L. (1930). Langston Hughes. [Photograph.] https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LOCEON_1039796913.

Cook, S. (2005). Holiday, Billie. In D. C. Hine (Ed.), Black Women in America. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156775.001.0001/acref-9780195156775-e-0194.

Gottlieb. W. P. (February 1947). Billie Holiday. [Photograph]. Downbeat. New York, N.Y., c. Feb. 1947. [Photograph]. Washington D. C. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. ID LC-GLB23-0425 DLC. https://loc.gov/item/gottlieb.04251.

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 1: The Negro in an African Setting. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003019815.

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 2: From Slavery Through Reconstruction. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003019831.

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 3: an Idyll of the Deep South. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://awaveofchangeexhibition.wordpress.com/2015/07/21/an-idyll-of-the-deep-south/.

Douglas, A. (1934). Aspects of Negro Life. Panel 4: Song of the Towers. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003152087.

Holiday, B. (1939). “Strange Fruit.” [Audio Recording]. http://www.billieholiday.com/portfolio/strange-fruit/.

Hughes, L. (1926). “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” In The Weary Blues. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44428/the-negro-speaks-of-rivers.

Hughes, L. (1926). “The Weary Blues.” In The Weary Blues. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47347/the-weary-blues.

Hurston, Z. N. (1935). Mules and Men. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma01/grand-jean/hurston/chapters/index.html.

Hurston, Z. N. (1937). Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York: I. B. Lippincott, Inc. https://archive.org/details/TheirEyesWereWatchingGodFullBookPDF/page/n89.

Leininger-Miller, T. (2011). Harlem Renaissance. [Article]. Marter, J. (Ed.), The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195335798.001.0001/acref-9780195335798-e-861.

Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. (1930). [Photograph]. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Library, Loewentheil Collection of African-American Photographs, #08043. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7730736_7730736_9810307.

McLaren, J. (2010). Hughes, Langston. In F. Abiola Irele & B. Jeyifo (Ed.s), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334739.001.0001/acref-9780195334739-e-197.

Meeropol, Abel. (1939). “Strange Fruit.” http://www.billieholiday.com/portfolio/strange-fruit/.

Reiss, W. (c.1925). Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003019922.

Singh, A. (2009). Hughes, Langston. In P. Finkelman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of African American History 1896 to the Present. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195167795.001.0001/acref-9780195167795-e-0587.

Sleet, M. Jr. (1956). Portrait of Billie Holiday. [Photograph]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001331733.

Strange Fruit. (n.d.). http://www.billieholiday.com/portfolio/strange-fruit/.

Zora Neal Hurston [Photograph]. (1935-1943). Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-62394. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004672085/.

a slow jazz song of lamentation, generally for an unhappy love affair. Usually in groups of 12 bars, each stanza being 3 lines covering 4 bars of music. … The earlier (almost entirely African-American) history of the blues is traced by oral tradition as far back as the 1860s, but the form was popularized about 1911–14 by the black composer W. C. Handy (Blues).

A kind of poetry that does not conform to any regular meter: the length of its lines is irregular, as is its use of rhyme—if any. Instead of a regular metrical pattern it uses more flexible cadences or rhythmic groupings, sometimes supported by anaphora and other devices of repetition. Now the most widely practiced verse form in English, it has precedents in translations of the biblical Psalms … but established itself only in the late 19th … with Walt Whitman (Free Verse).

“a figure in which one thing, idea, or action is referred to by a word or expression normally denoting another … so as to suggest some common quality … assumed as an imaginary identity rather than directly stated as a comparison: e.g. referring to a man as that pig. … Everyday language is made up of metaphorical phrases that pass unnoticed as “dead” metaphors, like the branch of an organization.” (Metaphor).

repetition of the same word or phrase in several lines of text (Anaphora).

a balanced arrangement of textual elements achieved through repetition of the same syntactic forms that is, types of words or phrases in an expression (Parallelism).

a type of verse that “records the names of several persons, places, or things in the form of a list.” It is common in epic poetry (e.g. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey), in free verse (e.g. Walt Whitman), and powerful oratory, (e.g. Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech) (Catalogue).

a division of the poem rather like a prose paragraph and characterized by patterns of rhyme or meter. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines.

a short poem traditionally celebrating pastoral, i.e. rural life.

French term for a type, species, or class of composition with common conventions (“Genre”).