Images and Tales of Mortality

Spiritual Dimensions of Art

- Evocation of a mysterious human inwardness …

- Yearning to transcend life & death …

- And connect with forces of creation

These spiritual concerns constellate around the great human challenge: mortality and the yearning for transcendence. Nothing is more centrally human, or more spiritual.

Egyptian Funerary Art: Books of the Dead

All human beings share a spiritual problem: how to face death, inevitable but radically unimaginable. Ancient Egyptian art was focused intensely on mortality. Most of it was funerary, intended for inclusion in tombs. Even the vast monuments intended to awe onlookers and project Egyptian power were often connected with tombs. One of the most pervasive genres of Egyptian funerary art was the so-called Book of the Dead, inscribed on papyrus, in amulets, and inside the coffin of mummies from people at numerous strata of society.

Book of the Dead… is the name that German Egyptologists gave to the collection of writings that the ancient Egyptians called … Chapters of the Coming Forth by Day … in the interest of guiding the deceased through the afterlife. It first appeared …[between] 1800 and 1530 BCE. …

The ancient Egyptians … believed that when one died it was necessary to have at one’s disposal the chants or passwords that would call the names of the gods and thereby guarantee safe passage to … overcome the hazards that filled the afterworld. …

|

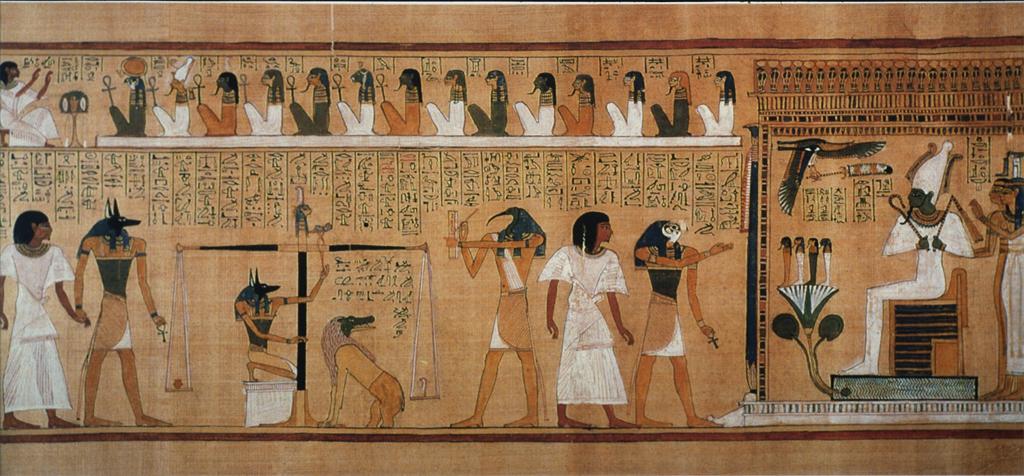

| Book of the Dead (c. 1317-1285 BCE). Psychostasis scene (judgment of the dead before Osiris). Ink on papyrus. |

The Book of the Dead guides the souls in safely navigating the passage into the afterlife. One of the most important tests is divine judgment: the soul of the departed comes …

before Ausar and the forty-two judges, representing different aspects of Ma’at, Divine Justice. …The deceased comes before the judges for the weighing of the heart by the feather of Ma’at. The deceased had to call each judge by name and give the relevant chapter, or “declaration of innocence” … “O Far Strider of Ionnou, I have done no falsehood; O Fire-Embracer from Kherarha, I have not robbed: “O Nosey of the city of Djehuty, I have not been greedy.”

When the deceased had gone through the entire citation of the forty-two declarations of innocence, it was expected that the deceased would be declared “justified,” that is, true of voice, and then ushered into the realm of the deceased where the gods await. The devourer of the dead, the demon Ammut, awaited those who would fail the test, but the outcome was always one that was optimistically successful, that is, that the deceased would be ushered into the realm of the deities (Kete Asanti)

As knowledge of Christian saints helps us process ecclesiastical art, knowledge of Egyptian deities help us to identify some key subjects and objects in this scene:

- The white-robed figure–the deceased

- Anubis, jackal-headed god leading the deceased up to and beyond the scales of judgment

- Scales of Maat on which the heart (a pot) must balance a feather of truth

- Ammit, crocodile-headed “devourer” of those who fail the test

- Thoth, the Ibis headed god who inscribes the judgment

- Osiris, enthroned king of the underworld backed by his sisters, Isis and Nephthys

The fully developed Egyptian concept of a judgment in the afterlife was influential in many cultures. Some scholars see parallels in the Christian concept of the day of judgment.

Lamentations of Job

|

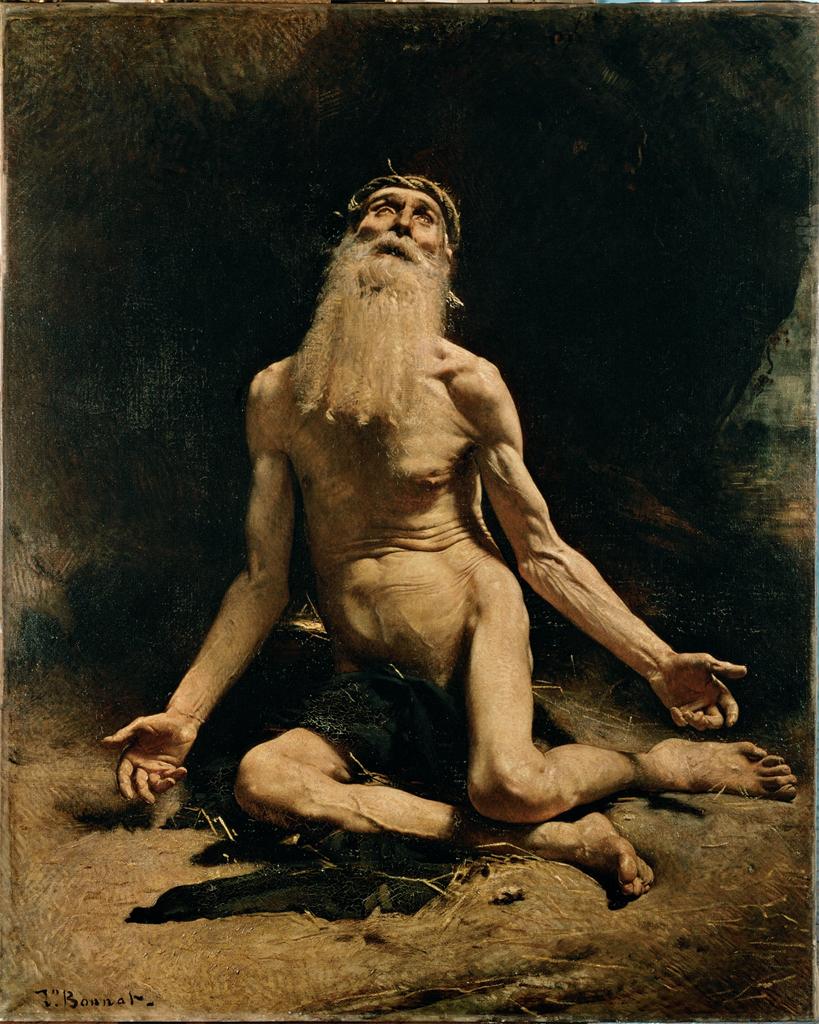

| Léon Bonnat. (c. 1860). Job. Oil on canvas. |

We said above that the Jewish tradition did not say much about heaven or hell. But we do find in Hebrew scripture a stirring affirmation of our hope of eternal life. Job is a wise and righteous man whose faith is tested by bad fortune. He loses his herds, his children and his health. Worst of all, his friends conclude that his misfortunes MUST indicate that God is punishing him. Job persists and continues to assert his faithfulness even in a disputation with God himself. Yet job, in the depth suffering, rings out his faith in God’s eternal life.

Lamentations of Job. 19.25-27 (Bible Gateway link)

and that at the last he will stand upon the earth;

and after my skin has been thus destroyed,

then in my flesh I shall see God,

whom I shall see on my side,

and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

My heart faints within me.

The Death of Death: John Donne

|

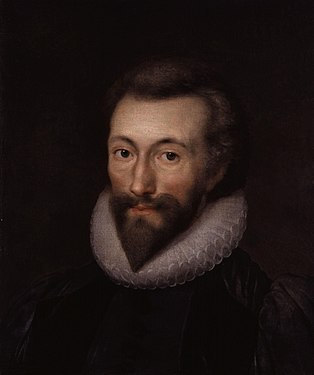

| Oliver, Isaac. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. |

Like Job, John Donne finds in his faith a stirring response to death. After a secular career, Donne in 1621 entered the clergy as Dean of St. Paul’s cathedral. In 1623, he contracted an illness that brought him near to death. In 1624, Donne published a series of reflections on his near-death experience. Meditation XVII attempts to bridge the gap between someone else’s funeral bells and our own mortality:

John Donne. from Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions. (1624)

Perchance he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him. … The church is Catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does belongs to all. … When she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author. … As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness. …

If we understand aright the dignity of this bell that tolls for our evening prayer, we would be glad to make it ours by rising early, in that application, that it might be ours as well as his, whose indeed it is. The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God.

Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? but who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world? No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee. In these famous words, Donne offers a literary memento mori, the medieval practice of keeping a skull on one’s desk as a reminder of death. In this Holy Sonnet, he celebrates the triumph of faith over death.

John Donne,Holy Sonnet #10. (1633)

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be,

Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

[1] Poppy: in Donne’s time, poppy seeds were taken to dull pain and to help one fall asleep.

Reading Donne is always a challenge, but perhaps you are more prepared now to track the themes of the English sonnet. Stanzas 1 through 3 each answer the apparent power of death through comparisons which show its weakness. That final, stinger couplet embraces the triumph of Christian faith: the death of death in Christ.

Genteel Death: Emily Dickinson

|

| Portrait of Emily Dickinson (c 1847). Daguerrotype. |

Although writing in literary seclusion in western Massachusetts … Emily Dickinson invented a poetry both unprecedented in form and long-lasting in impact. She wrote as if to bid farewell to the Victorians and to urge on the modernists (Dickinson, Emily).

Emily Dickinson lived a virtually anonymous life in silent resistance to conventional social expectations. At Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, “Dickinson remained seated while everyone else stood” in affirmation of a speaker’s invitation for the women to be Christian. She returned home and lived in seclusion, composing poems destined for letters to friends and her desk drawer. Among her themes was the impossible challenge of imagining death.

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air –

Between the Heaves of Storm –

The Eyes around – had wrung them dry –

And Breaths were gathering firm

For that last Onset – when the King

Be witnessed – in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes – Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable – and then it was

There interposed a Fly –

With Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz –

Between the light – and me –

And then the Windows failed – and then

I could not see to see –

Dickinson’s verses can seem strange. Who would imagine death as a genteel suitor or the fly buzzing in the room at the point of death? Then again, who can imagine the point of one’s own death? Dickinson tackled the challenge of imagining death with the same courage she showed in resisting the social conventions which she found so stifling.

Emily Dickenson,Because I could not stop for Death (479)

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer[2], my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle[3] –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice[4] – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

In this famous poem, Dickinson imagines death as a genteel suitor calling for her in a carriage bearing her into infinity. Notice the details: the bridal veil, the destination as a swelling in the ground, the absorption of time into a timeless infinity. To suggest the featureless and unknowable, Dickinson catalogues features of daily life her journey leaves behind.

Mortality and the Ancestors: Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo[5] was born in Mexico City to a German immigrant father and a mestizo[6] mother. As an artist, she worked primarily in self-portraits, albeit self-portraits of a unique type. In surreal compositions, she explored her herself internally and externally, probing the textures of her mortality. The Two Fridas reflects a culturally split self, attired in dresses from each culture, with two hearts connected by a tenuous line of blood.

[5] For more information, see this brief article on Frida Kahlo.

[6] Mestizo: i.e. a Mexican of mixed ethnic origins—European and indigenous

|

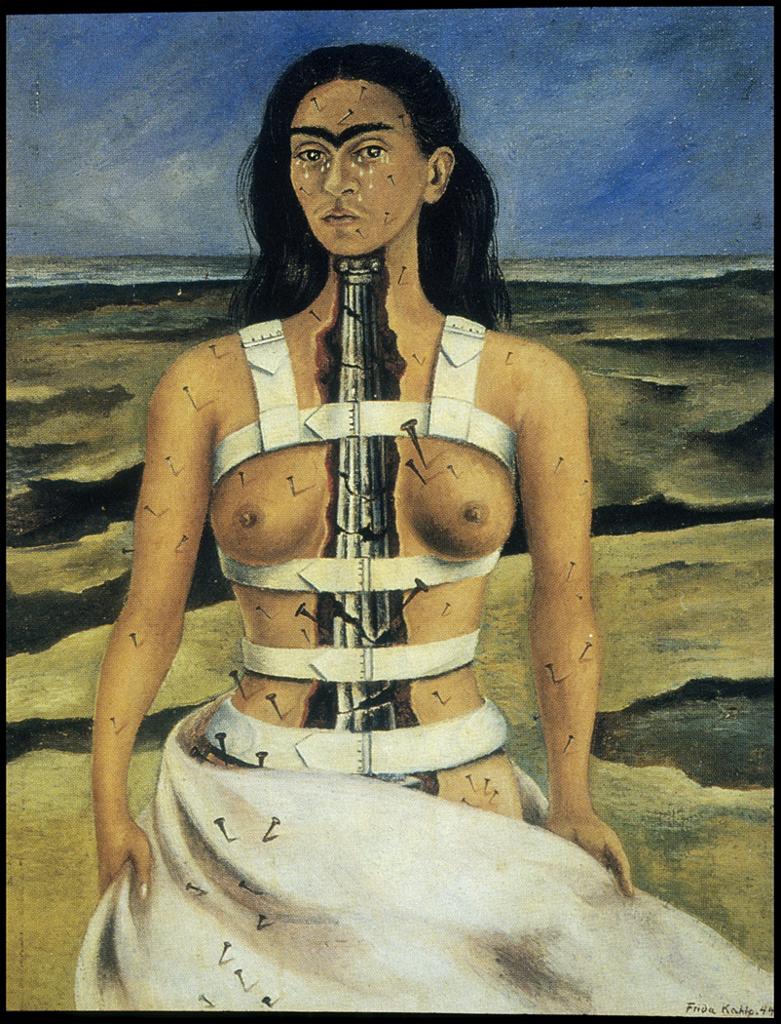

|

|

| Las Dos Fridas [The Two Fridas]. (1939) | Broken Column. (1944). Oil on canvas. | El Sueño (La Cama) [The Dream (The Bed)]. (1940). |

For Kahlo, art was, quite literally, a chronic wrestling with death. After suffering a crushed spine in a bus accident while a teenager, Kahlo endured numerous operation and hospital stays lying flat on her back. She painted in hospital beds, her canvases perched above her. The Broken Column transforms her spinal column, never whole again after the wreck, into art, a Greek architectural column. The Dream (The Bed) uses Surrealist visual logic to evoke a traditional paradox., In traditional cultures, children are conceived and eventually die in beds at home. Recalling that Mexican culture cultivates a very strong , we can see Kahlo’s dream work connecting with those who have gone before her.

References

Bonnat, Léon. (c. 1860). Job [Painting]. Bayonne, France: Musée Bonnat. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310483824.

Book of the Dead (Hunefer Papyrus) (c. 1317-1285 BCE). Psychostasis scene (judgment of the dead before Osiris, god of the underworld). Ink on papyrus. London, UK: British Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_960012.

Dickinson, E. (circa 1868). Poem 479. In R. W. Franklin (Ed.), (1999) The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. , Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47652/because-i-could-not-stop-for-death-479.

Dickinson, E. (circa 1868). Poem 591. In R. W. Franklin (Ed.), (1999) The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. , Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45703/i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died-591

Donne, J. (1633). Poem #10. In Holy Sonnets. In Holy Sonnets. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44107/holy-sonnets-death-be-not-proud.

Kahlo, F. (1939). Las Dos Fridas [The Two Fridas] [Painting]. Mexico City, Mexico: Museo De Arte Moderno. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ASCHALKWIJKIG_10313992050.

Kahlo, F. (1940). El Sueño (or La Cama) [The Dream (or The Bed)] [Painting]. Private collection. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LARRY_QUALLS_10310502487.

Kahlo, F. (1944). Broken Column [Painting]. Mexico City, Mexico: Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ABARNITZ_10310364250.

Kahlo, Frida [Article]. (2016). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1835.

Kete Asante, M. (2010). Book of the Dead. In F. Abiola Irele & B. Jeyifo (Ed.s), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195334739.001.0001/acref-9780195334739-e-078.

McQuade, M. (2004). Dickinson, Emily. In J. Parini & P.W. Leininger (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195156539.001.0001/acref-9780195156539-e-0065.

Munch. E. (1892). Death in the Sickroom [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Accession: 17102. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AMCADIG_10312186791.

Munch. E. (1894-1895). Melancholy [Painting]. Minneapolis MN: Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Accession: 20916. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMCADIG_10313213787.

Munch, E. (1893). Scream [Painting]. Oslo: National Gallery of Norway. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000862282.

Oliver, I. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1849. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Donne_by_Isaac_Oliver.jpg.

Portrait of Emily Dickenson [Daguerreotype]. (c 1847) Amherst, MA: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black-white_photograph_of_Emily_Dickinson2.png.

Rembrandt van Rijn. (1633). Storm on Sea of Galilee [Painting]. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000427318.

reminder of mortality (Latin). A reference to Medieval monks' practice of keeping a skull or other skeletal element in view within their cell to maintain at all times an awareness of their mortality,

A short rhyming lyric poem, usually of fourteen lines of iambic pentameter.

a division of the poem rather like a prose paragraph and characterized by patterns of rhyme or meter. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines.

a verse stanza of 2 lines.