Teaching Fidelity to the State

About 6,000 years ago, the practice of agriculture transformed societies in various parts of the world. Agriculture required extensive social organization and produced surpluses which had to be protected. The result was what we loosely recognize as civilization, stratified societies with unequal distributions of wealth and power. Some wealthy societies developed ruling elites and armies of conquest. Such societies have always used art to affirm the legitimacy and glory of the state. Let’s glance at three examples.

Below, we see the figure of the Dying Gaul, a representative of the native peoples to the north and west of Italy who resisted Roman rule for generations before being subdued by Julius Caesar. Representations of defeated enemies in other ancient cultures often demean the vanquished by depicting them in small scale and in positions of servitude. This sculpture depicts a noble, dignified warrior who has fallen in battle. The image flatters the Empire by humanizing and respecting the enemy it has conquered.

|

|

|

| Dying Gaul. (ca. 230-220 BCE). Sculpture. | Jaques-Louis David. (1802). Napoleon Crossing the Saint Bernhard Pass. Oil on canvas. | Leutze, Emanuel. (1851). Washington Crossing the Delaware. Painting. |

Over 17 Centuries later, a Corsican gunnery officer in the French Army sought to rebuild the glories of Ancient Rome by conquering Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Russia. Napoleon Buonaparte, the scourge of other European nations, fired in the French breast an immense sense of gloire (glory) that has not fully died out even today. Jaques-Louis David’s invests his vision of Napoleon astride a horse with gloire, the French term for glory all but monopolized by the Emperor’s cult. Note: later, we’ll look at Goya’s much less flattering portrait of Napoleon from the perspective of his ambition’s victims.

The revolution in France that led to Napoleon’s ascendancy was inspired by one among 13 British colonies in North America. Emmanuel Leutze’s painting of a heroic moment in the American Revolution celebrates one of the iconic moments of a national history imbued with the legend and virtues of democracy. Didactic Art has through the ages celebrated the state and enhanced popular support.

Shamash and Hammurabi

In the ancient world, power always claimed the blessing of divine favor. Kings, often seen as divine, served as priests, mediating between the people and the gods. Often, gods were thought to live in temples attended by royal high priests. If a city or nation succumbed to famine, plague, or an enemy’s armies, clearly the king/priest had lost the favor of the gods who were believed to have literally abandoned the building.

Hammurabi reined in the 1st dynasty of Babylon. Babylonian kings are prominently featured in Hebrew scripture (for Christians, the Old Testament). Yet Hammurabi’s era was much older than the neo-Babylonian empire that conquered the Israelite kingdom of Judah in 605 BCE (relevant Hebrew scriptures: Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Lamentations, and more).

|

|

|

| Royal Head [Hammurabi?]. (2nd millennium BCE). | The Code of Hammurabi. (ca. 1792-1950 BCE). Engraved black basalt. | Detail: Hammurabi before Shamash |

Hammurabi’s glory is commemorated in a basalt stele (or stela), a monument that affirms the king’s authority by portraying him in supplication before Shamash, a Babylonian god (see the detail). Steles were often set up by powerful rulers to affirm their authority, to delineate a realm’s boundaries of a realm, or to commemorate military triumph. But this one has a remarkable feature.

Didactic Art teaches not only subservience to the state but also how to behave. The key to Mesopotamian prosperity was an elaborate system of irrigation channels that had to be maintained. Hammurabi’s stele inscribes a complete legal code, one of the world’s first, and a major concern of its provisions is with the proper maintenance of those irrigation systems.

The Code of Hammurabi

The Laws of Hammurabi are the most famous and complete of the ancient Mesopotamian law collections. There are 275–300 laws in Hammurabi’s collection, … carved on a cone‐shaped black diorite stela that stands over two metres tall. … The Babylonian god of justice, Shamash, is seated at the top of the stela, dictating the laws to Hammurabi. …In addition to the laws themselves, there is a poetic prologue, recounting Hammurabi’s accomplishments and articulating his desire to establish justice, and … cursing those who might deign to disobey his laws. (Versteeg, 2008, para. 4)

Ancient Egypt

A noteworthy example of Didactic Art supporting a society is that of ancient Egypt. As is the norm, similarly affirms a society, its leaders, and its claims to divine patronage. The Narmer Palette below commemorates the military and political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one rule (3,000 BCE).

|

|

| Narmer Palette (Obverse face). (ca. 3000 BCE). Slate relief. | Narmer Palette (Reverse). (ca. 3000 BCE). Slate relief. |

The faces of the palette are divided into “registers,” or zones which affirm Narmer’s authority through his close relationship with the gods. At the top, we see the invocation of a deity, the cow goddess Hathor. In the middle register (obverse face), we see King Narmer smiting an enemy under the gaze of the falcon god Horus.

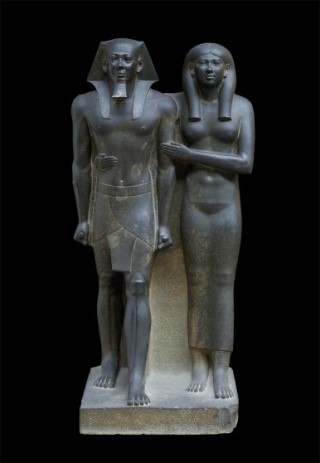

Your sharp eye will notice the difference in size between the king and other figures in the image. In many ancient traditions, difference in scale conventionally indicates social status. The image of the Pharaoh Menkaure is dominated by the goddess Hathor, seated and a bit larger than the Pharaoh, Hathor’s attributes of the cow and the heavens are represented by her headdress: a solar disk between horns. Smaller still is Hare, a deified personification of a region of Egypt.

|

|

|

| Menkaure, Hathor, and Hare. (26th Century BCE). Sculpture. | King Mendaure & Queen. (25th Century BCE). Sculpture. | Hunting Scene. (ca. 1415 B.C.). Tomb of Menna (no. 69). Painting. |

What do you think of the depiction of Menkaure with his wife? Does it seem familiar? These royal figures strike a pose strictly conventional in Egyptian sculpture: erect stance, feet flat with one advanced, the king’s arms straight with fists clenched. The faces are impassive and impersonal, capturing no emotion or individuality. Remarkably, this style remained largely unchanged through scores of royal dynasties over 2,500 years. This level of stylistic continuity clashes with contemporary artistic values. Great art, we think today, throws over the stale patterns of the past and boldly explores personal visions. What sort of artists do the same thing for 2,500 years?

The answer is simple: these artists expressed a very different cultural perspective. The function of art in ancient Egypt was to affirm the myth of an enduring people. Egyptian wealth and power were based on the predictability of the Nile River’s gift of fertility to a strip of land in a hostile desert. Every year, the Nile flooded and receded. Every generation of Pharaoh continued the authority of those before. Egyptian art reflected a conservative, consistent, stable culture.

The Hunting Scene captures the prosperity conferred by the Nile through multiple levels of society. The Nile teems with fowl and fish, signifying the fecundity of its river valley. The nobleman hunts with his wife, servants, and slaves, each figured sized according to social status. The figures are depicted in a distinctive, timeless, two-dimensional style. As is true of nearly all ancient Egyptian painting, the figures are presented in profile, but some combine two perspectives: feet and heads in profile, torsos turned toward the viewer.

Egyptian art, then, attempts to stave off the destructive effects of time: generations may come and go, but our civilization, our personal lives, endure. Ancient Egyptian art was mostly funerary, focused on the transition from life on earth to the underworld. Not only did the “art” of mummification seek to preserve the body, but carved and wrought figures and vehicles in an Egyptian tomb provided the deceased with food, conveniences, and servants into eternity.

|

|

| Colossi of Memnon. (1372 B.C.). Sculpture. | Colossi of Ramses II. (ca. 1270 B.C.). Temple. Abu Sunbul. Sculpture. |

From ancient kings to corporations in our age, the powerful erect massive, monumental buildings and art works to intimidate and assert power. Ancient Egyptian architecture and statuary—the pyramids, the Sphinx, the temple compound at Luxor—were erected to project power and affirm the blessing of the gods in opposition to every rival … now and in the future. Colossal statues of pharaohs like Ramses II sought to intimidate generations yet unborn.

Shelley and Ozymandias

|

| Curran, Amelia. (1819). Portrait of Percy B. Shelley. Oil on canvas. |

Of course, no one beats time. Pharaohs died. The empire was repeatedly defeated, finally by Greeks and Romans. Over the centuries, even the monuments eroded, crumbled, and collapsed. In 1818, the English poet Percy Byssche Shelley was intrigued by press drawings of archeological discoveries in Egypt. Eroding monuments, such as the Colossi of Memnon, invoked the irony of human aspiration.[1]

[1] As quoted in Mikics, Shelly’s poem channels the irony of an ancient Roman historian named Diodorus who quoted an inscription on an Egyptian monument: “King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley. Ozymandias (January 11, 1818)

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Elizabethan England

|

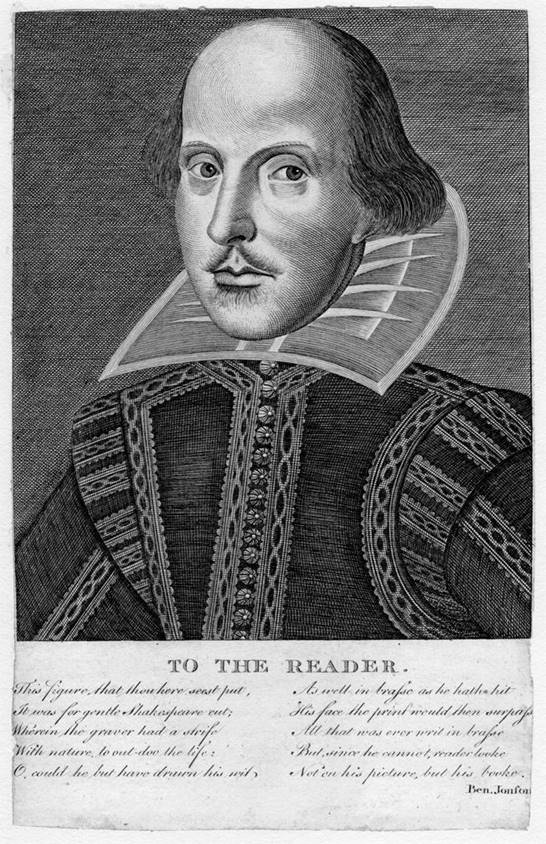

| Shakespeare, W. (17th Century). Frontispiece, First Folio. |

All societies celebrate the heroes that embody the ideals they imagine at the core of their national characters. Between 1590 and 1610, William Shakespeare wrote and directed plays in the flourishing theater scenes in London and the provinces. Now, Shakespeare’s dramas were composed under especially constraining circumstances. Playwrights of Shakespeare’s day had to be sponsored—i.e. officially authorized—by English aristocracy: lords, ladies, and Queen Elizabeth, who eagerly sponsored the arts. Clearly, their plays were required to teach the lesson of fidelity to their patrons’ authority.

Furthermore, Queen Elizabeth was vulnerable to bad publicity. Her Tudor grandfather, Henry VII, was thought by many to have usurped (stolen) the crown. Her father, Henry VIII, had broken with Rome and was condemned throughout Catholic Europe. Elizabeth’s navy had to fight off the massive Spanish Armada, sent to invade and re-impose Roman Catholic authority. Oh, and Elizabeth was a ruling queen in a world of kings and patriarchs. Tudor England needed support from all of its poets.

Henry V, Act 4, Scene 3 by William Shakespeare

He which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made

And crowns for convoy put into his purse:

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is called the feast of Crispian[2]:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when the day is named,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbors,

And say ‘To-morrow is Saint Crispian:’

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day. …

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,[3]

This day shall gentle his condition:[4]

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

[2] Crispin’s day: the calendar of the medieval church listed many holy days (holidays) that honored various saints. Crispin and Crispian were Christians martyred during the 3rd Century persecutions of Diocletian.

[3] Vile: this word refers to social caste—the sense is no matter how low of birth.

[4] Gentle his condition: think of gentleman—the word gentle refers to a rank within the aristocratic upper classes. Henry is saying that veterans of this battle will rise to a higher social caste.

Astonishingly, Henry’s small army routed the French, in large part because of non-aristocratic long bowmen who had the audacity to slay hundreds highborn French knights from afar. To this day, the British revere Agincourt as one of England’s greatest victories. Shakespeare’s speech has rung through the ages and continues to inspire soldiers and athletes even today. Every time you see the phrase “band of brothers,” Shakespeare’s words live on.

The play has twice been notably filmed. Lawrence Olivier directed and starred in a 1943 production to rally English spirits during World War II. In 1989, Kenneth Branagh also directed and played the lead role in a revival (Video of the “Band of Brothers” scene , technicalmark, 2009). Today, it is quoted and cited all over the world to motivate peoples in crisis and sports teams facing adversity.

References

Abu Simbel: Ramses II temple: Ext.: Facade: Four Colossi of Ramses II and Terrace [Temple]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003586557

Colossi of Memnon: Front reign of Amenhotep III, Western Thebes [Sculpture]. (1372 B.C.). ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000132900

Curran, A. (n.d.). Portrait of Percy B. Shelley [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001651528

David, J.-L. (1801-1802). Napoleon crossing the Saint Bernhard Pass. [Painting]. Chateau de Versailles, Versailles, France. ARTstorhttps://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490372

Dying Gaul [Sculpture]. (ca. 230-220 BCE). Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490325

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen [Sculpture]. (2490-2472 B.C.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, United States. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AMBOSTONIG_10313608722

Leutze, E. (1851). Washington crossing the Delaware. [Painting]. Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, NY, United States. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/MMA_IAP_1039651608

Narmer Palette (Obverse face) [Slate relief]. (ca. 3000 BCE). The Archive for Research on Archetypal Symbolism, New York, NY, United States. ARTstor

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31674620

Narmer Palette (Reverse) [Slate relief]. (ca. 3000 BCE). The Archive for Research on Archetypal Symbolism, New York, NY, United States. ARTstor

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31674622

Royal head, called the head of Hammurabi [Sculpture]. (Beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE). Musee du Louvre, Paris, France. ARTstor

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10311440732

Shakespeare, W. (n.d.). The life of King Henry the fifth. Project Gutenberg. https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1011000&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Shelley, P. (January 11, 1818) “Ozymandias.” London: The Examiner. Retrieved from Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69503/percy-bysshe-shelley-ozymandias#poem.

technicalmark. (2009, May 3). Henry V – Speech – Eve of Saint Crispin’s Day – HD [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/A-yZNMWFqvM

The Code of Hammurabi. (ca. 1792-1750 BCE). [Sculpture]. Musee du Louvre, Paris, France. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490426

Triad of King Menkaure (Mycerinus), the goddess Hathor, and the deified Hare nome [Sculpture]. (2532-2510 B.C.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, United States. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AMICO_BOSTON_103829342

Versteeg, J. R. (2008). Ancient Middle Eastern law. In P. Cane & J. Conaghan (Eds.), The new Oxford companion to law. Oxford University Press.

https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199290543.001.0001/acref-9780199290543-e-69

Wall [Hunting scene] [Painting]. (ca. 1415 B.C.). The Archive for Research on Archetypal Symbolism, New York, NY, United States. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31676036

art that is instructive, designed to impart information, advice, or some doctrine of morality or philosophy. The dominant focus of most ancient and Medieval art (didactic).