Introduction: You and the Arts

Cool. But … let’s explore that. For example, do you like poetry? No? What about song lyrics? Do you ever sing favorite lyrics because they move you? Well, that’s poetry, Lyric Poetry:

Lyric Poetry

A term usually applied to short poems expressive of a poet’s thoughts or feelings; as a broad genre, it includes such forms as the Sonnet, ode, and elegy along with many other varieties deriving from popular song. The term originally referred to a Greek song to be accompanied on the lyre, but later became associated with song‐like poems uttered by a single speaker (Lyric Poetry).

This definition applies to the “words” of popular songs today. We inherit the term from Greek playwrights (e.g., Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes) who, five centuries before Christ, dramatized stories from their mythology. The lyric portions of these plays were accompanied by the lyre (a stringed instrument similar to a harp). In the Euro-American literary tradition, lyric is applied to “the sonnet, ode, and elegy, along with many other varieties deriving from popular song.”

Martin Luther: A Mighty Fortress is Our God

One lyrical Genre is the hymn. Let’s explore a Protestant standard.

Martin Luther. A Mighty Fortress is Our God (Lyrics and Audio file)

- A mighty Fortress is our God,

a Bulwark never failing;

Our Helper He amid the flood

of mortal ills prevailing:

For still our ancient foe

doth seek to work us woe;

His craft and power are great,

and armed with cruel hate,

On earth is not his equal. - Did we in our own strength confide,

Our striving would be losing;

Were not the right Man on our side,

The Man of God’s own choosing:

Dost ask who that may be?

Christ Jesus, it is He;

Lord Sabaoth His Name,

From age to age the same,

And He must win the battle. - And though this world, with devils filled,

Should threaten to undo us,

We will not fear, for God hath willed

His truth to triumph through us:

The Prince of Darkness grim,

We tremble not for him;

His rage we can endure,

For lo! his doom is sure,

One little word shall fell him. - That word above all earthly powers,

No thanks to them, abideth;

The Spirit and the gifts are ours

Through Him who with us sideth:

Let goods and kindred go,

This mortal life also;

The body they may kill:

God’s truth abideth still,

His Kingdom is forever.

Translated by F. H. Hedges.

This hymn is a favorite for Protestant worshipers. But the more we know of the Context of its composition, the more we appreciate the lyrics. The hymn was one of many written by the 16th Century monk and scholar Martin Luther who braved the wrath of the Roman Church to challenge Papal authority. In 1521, Luther confronted the Holy Roman Emperor and papal representatives to defend his ideas. He was condemned to excommunication and death. Yet, God led him to sanctuary in a “might fortress,” Wartburg Castle, owned by Frederick III of Saxony. Think of that place of sanctuary when you hear or sing this hymn.

Woody Guthrie: This Land is Your Land

As do residents of every country, Americans are inspired by songs celebrating their nation. Listening to Woody Guthrie’s This Land is Your Land (1940), many Americans celebrate the magnificence of their national landscape.

Woody Guthrie. (1940) This Land is Your Land

- This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York island,

From the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters;

This land was made for you and me. - As I was walking that ribbon of highway

I saw above me that endless skyway;

I saw below me that golden valley;

This land was made for you and me. - I’ve roamed and rambled and I followed my footsteps

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts;

And all around me a voice was sounding;

This land was made for you and me. - When the sun came shining, and I was strolling,

And the wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling,

As the fog was lifting a voice was chanting:

This land was made for you and me.

Listen to Woody Guthrie’s performance of his song: link.

Do you dislike “poetry” but enjoy song lyrics? Many negative attitudes overlook unsuspected roles played by the arts in their lives. Enjoy lyrics and you are enjoying poetry!

What is Art?

OK, so what counts as art? What doesn’t? Obviously, painting and sculpture are widely seen as art. However, we will also consider poetry and prose fiction as arts. We will now and then nod to the artistic dimensions of photography, architecture, and other artistic endeavors.

But wait: paintings, sculpture, poems, stories—do they always count as art?

- Does art require a certain level of excellence to count?

- Must art be original, ground-breaking, innovative?

- Can art serve commercial purposes?

- Can beautiful scenery created by God count as art?

These are great questions and they have been disputed for many years by artists and philosophers. We can’t resolve the thorny issue of defining art in our class. What we can do is notice that various traditions of artistic endeavor tend to share certain shared hallmarks.

Hallmarks of Art, class definition

- Compositions of the human imagination

- Craft and artifice drawing on tradition, technique, and technology

- Themes and patterns of meaning

- Stimulation of aesthetic experiences: beauty, ugliness, the sublime

- Ideological and spiritual inspiration

Aesthetic Reactions to Art

Did you notice that word, aesthetic? Aesthetic Attitude refers to a specific way of looking:

A term usually applied to short poems expressive of a poet’s thoughts or feelings; as a broad genre, it includes such forms as the sonnet, ode, and elegy, along with many other varieties deriving from popular song. The term originally referred to a Greek song to be accompanied on the lyre, but later became associated with song‐like poems uttered by a single speaker. (“Lyric Poetry,” 2012)

The aesthetic attitude is supposedly a particular way of experiencing or attending to objects. It is said to be an attitude independent of any motivations to do with utility, economic value, moral judgement, or peculiarly personal emotion, and concerned with experiencing the object “for its own sake.”

At the limit, the observer’s state would be one of pure detachment, marked by an absence of all desires directed to the object. It could be … an episode of exceptional elevation wholly beyond our ordinary understanding of empirical reality, … or simply as a state of heightened receptiveness in which our perception of the object is more disengaged than usual from other desires and motivations which we have. The term “disinterested” is often applied. (Janaway, 2005)

You watch a beautiful sunset over the water. You are pleased, perhaps moved by the beauty. But you receive no tangible benefit. The spectacle pays you no money. Gains you no power. Confers no health. The sunset’s beauty has no moral dimension. You respond to sheer beauty.

The aesthetic dimension of art refers to the feelings evoked by its pure form: color, light/shadow, sound, pattern, rhythm—the features that confer an experience of beauty or ugliness. Of course, aesthetic responses are subjective. People differ in their reactions.

What Do You Like?

|

|

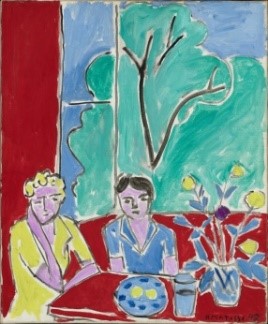

| Sargent, John Singer. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew. Oil on canvas. | Matisse, Henri. (1947). Two Girls, Red and Green Background. Oil on canvas. |

|

|

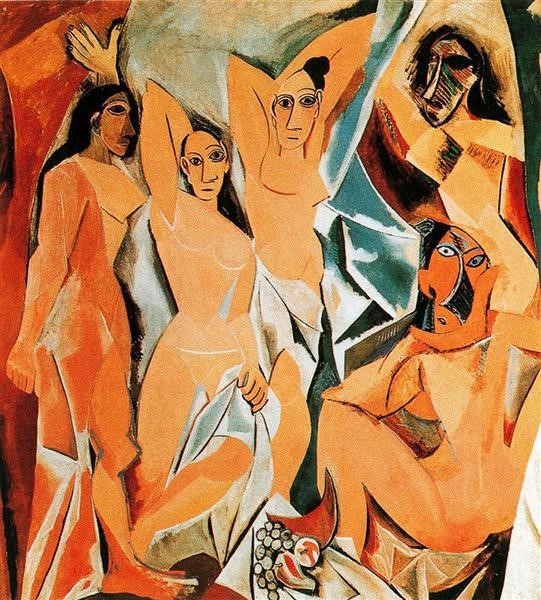

| Lucas Cranach the Elder. (1502) Portrait of Dr. Johannes Cuspinian. Tempera on red beech. | Picasso, Pablo. (1907). Les Memoiselles d’Avignon. Oil on canvas. |

|

|

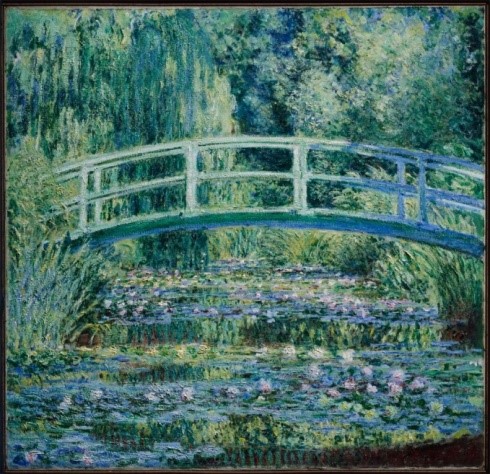

| Monet, Claude. (1899). Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge. Oil on canvas. | Pollock, Jackson. (1950). Number 18. Oil and enamel on Masonite. |

Well? What do you think? (Be sure to click on or hover over the thumbnails to see richer reproductions.) And what seems to determine your response? Familiarity? Your understanding? Surprise? A visual puzzle? Our responses to art reflect familiarity and understanding. Consciously or not, we are conditioned to respond comfortably to a Genre, certain kind of art:

Genre

The French term for a type, species, or class of composition. A literary genre is a recognizable and established category of written work employing such common conventions as will prevent readers or audiences from mistaking it for another kind (Baldick, 2015b).

At the movies, do you like rom-coms (romantic comedies)? Urban fantasies? Super hero flicks? Film noir? All are cinematic genres with which you are familiar. In the visual arts, the term Genre Painting refers to “paintings or other works depicting scenes from daily life” which have retained their appeal ever since the genre was pioneered by 17th-century Dutch artists. Those Dutch interiors and Still Life compositions are perennially popular because they are familiar in subject matter and in technique. A Genre, is defined by Convention.

Convention

An established practice—whether in technique, style, structure, or subject-matter—commonly adopted in [artistic] works by customary and implicit agreement or precedent rather than by natural necessity (Convention).

Conventions guide artists in producing their works. They also contribute to an audience’s understanding. Our reading of the arts deepens as we become aware of the impact of conventions on our reactions. In a rom com, the primary characters initially clash, setting up the final resolution: true love. Watching the opening conflict play out, we smile, reassured that we know where the story is going. To see the guiding hand of the convention is to understand the film and our response.

Of course, unrelieved clichés, excessive conformity to convention can be boring. A rom com that merely lurches from one stock scene to the next will put us to sleep. Artists who leave the biggest impression often challenge conventions in interesting ways. In great works, an interplay between comforting convention and surprising innovation lights the piece up for fascinated viewing. Baldick notes that “while some [artistic] works may be ‘unconventional,’ none can be convention less” (Convention).

On a larger scale, art is produced and experienced in a Context: the social, cultural, and historical milieu in which a work of art is composed and received by an audience. Or, perhaps, two contexts: that of the work’s production and that of the audience. We read Shakespeare today in a far different context from that of Elizabethan England. And contexts vary in their degree of tolerance for convention and for innovation. In the so-called “art world” of artists and aficionado, artists have since the era of Impressionism to be valued for originality, innovation, challenges to conventional social values, and individual vision.

As the divergence between conventional expectations and insurgent innovation has widened, the gap between the sensibilities of the Fine Arts world and those of the mainstream public have tended to widen. While some folks are drawn to avant garde work, many are put off by wholly unfamiliar, bewildering conventions which can lead to confusion, impatience, dislike, even fear. In which direction do you move when you encounter really challenging ideas or art?

Reading the Arts

So how shall we approach the arts? What will be expected of you? No, you are not expected to decide that you love all of the poems, stories, and paintings chosen for the class. Nor are you expected to discover hidden codes of meaning that only the instructor can see. You might be concerned about your limited knowledge base. Well, that’s OK. Ultimately, the work must speak for itself. Your work will be judged for the richness of your observations of and reflections on the work’s features.

Features of an artistic text or image to reflect on:

- Features of the text itself

- The sociocultural context in which the work was produced

- The maker’s life and background

- Genre, conventions and techniques that form the craft of the work

- Structures of meaning

Of course, readings grows richer as we become more knowledgeable. This text will provide an array of information on the Context and techniques that comprise the painting or poem or story. Furthermore, we will approach these works as a reading community, enriching each other’s senses of the works.

In your class readings and writings, draw on the materials we provide and on class collaboration. But when you select a work to focus on in your writing, bear down on your own, close reading. See. Hear. Observe. Pay attention to details. And share the richness of your reading with your reading community.

The Challenge of Encountering the Arts

Folks who avoid off putting art may feel some anxiety about a course like this. They may feel they have a poor general sense of the arts. They may worry about kinds of art that seem strange or incomprehensible. They may want to resist an expected pressure to like what the instructor likes.

Will we expect you to learn to like everything we explore? Not at all. Your ultimate reaction is yours to choose. Our text samples a wide range of arts, too many to engage in detail. The hope is that, each week, you will be intrigued enough by a few pieces to look more closely.

Sometimes, that means bravely engaging work that initially puts one off. We will ask you to make a good faith effort to give our selected works a chance to speak to you. We’ll be working on the challenge of engaging art that confuses or put us off. Here are some tips:

Responding to Unfamiliar or Challenging Art

Hold your initial responses loosely

Our initial responses to art—likes and dislikes, understanding and bewilderment—are often conditioned by our sense of the familiar. If we judge too quickly and harshly, we are likely to overlook work we could value and to misread its techniques and themes.

Look for indicators of context

Art’s features and conventions grow from cultural contexts. Obviously, we more easily and comfortably respond to art reflecting our own contexts. We are prone to recoil from work from times and cultures not our own. We can, however, increase our sensitivity to features suggesting another perspective. Always be cautious decoding work from a context foreign to you: might it mean something else in a different context?

Select and consult available information

To illuminate our readings, we will provide limited background information for our works of art. Each week, select a few works that “light up” for you and consult information provided, especially information on unfamiliar works that interest you.

Let the text or image speak for itself

Background information helps. But always let the text of image speak for itself. Be open to its expression of its own values and goals, which may differ from yours or from the conventional genre formulas. Rich readings are based on close, personal observation.

Respond honestly and openly

In our course, we’ll be asking you to give our poems, stories, and images a fair chance to speak to you, especially when illuminated by background information. However, you are not expected to ultimately decide to embrace anything. You might decide that, even after beginning to understand, you are not interested in a certain art form. You don’t gain extra points by liking our materials. We do expect you to read richly and thoughtfully.

The Special Challenge of Poetry

William Butler Yeats (May, 1914) A Coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies

From heel to throat;

But the fools caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eyes

As though they’d wrought it.

Song, let them take it

For there’s more enterprise

In walking naked.

Of all the arts, poetry is perhaps the one that causes the most anxiety in the most people. Many readers struggle to read verse, feeling that it often wrenches language out of normative patterns. OK, let’s try to ease the challenge a bit. Again, you won’t be asked to fall in love with poetry. However, you will be asked to bravely tackle some poems and explore their functions and patterns of meaning.

First, please try to believe that poems do nothing you don’t do with language. Poetic effects–e.g. Meter and Figures of Speech–are familiar to you if you learn to recognize them. You encounter them in daily speech, songs, and effective oratory. If poetry seems elusive, it is because poets push these effects further and with more cleverness than we are used to.

Second, although the full depth of poetry may seem elusive, that is not because it harbors secret messages only English teachers can see. Too many readers are so busy looking for secret messages that they can’t experience the overt sense and texture of the poem in itself. To enhance your experience of poetry, begin with the immediately available:

Tips on Reading Poetry

- Read aloud, listening for rhythms, patterns. (Click the button above to hear a reading of “Coat.”)

- Recognize the plain sense of the words before looking for hidden meanings.

- Who talks to whom about what? Clearly seeing this dynamic can open many poems.

- Track themes and patterns of meaning that flow from the above.

So … try to relax and let these great artists speak to you. You just might find yourself enjoying them!

References

Blake, W. (1794). The Ancient of Days [Relief etching]. British Museum, London, England.

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490359

Convention.(2015). [Article]. In C. Baldick (Ed.), The Oxford dictionary of literary terms (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-251?rskey=VnHfNQ&result=1

Cranach, Lucas the Elder. (c.1502-3). Dr. Johannes Cuspinian. [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000873941.

Genre. (2015). [Article]. In C. Baldick (Ed.), The Oxford dictionary of literary terms (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-493?rskey=UQauHB&result=1

Genre (2015). [Article]. Chilvers, I. [Ed.] The Oxford dictionary of art and artists (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-943?rskey=S7aJZY&result=10

Guthrie, W. (1940). This land is your land [Song]. Woody Guthrie. https://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/This_Land.htm

Janaway, C. (2005). Aesthetic attitude. Honderich, T. [Ed.]. The Oxford companion to philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199264797.001.0001/acref-9780199264797-e-30?rskey=wq9N4Y&result=1.

Luther, M. (n.d.). A mighty fortress is our God [Song]. Hymnal.net. https://www.hymnal.net/en/hymn/h/886

Lyric poetry. (2012). [Article]. In D. Birch & K. Hooper [Eds]. The concise Oxford companion to English literature (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-4695?rskey=Nlso8L&result=2

Matisse, H. (1947). Two girls, red and green background [Painting]. Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD. United States.

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ABALTIMOREIG_10313362726

Monet, C. (1899). Water lilies and Japanese bridge [Painting]. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ. United States.

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/APRINCETONIG_10313684987

Picasso, P. (1907). Les demoiselles d’Avignon [Painting]. Museum of Modern, New York, NY. United States.

https://www.wikiart.org/en/pablo-picasso/the-girls-of-avignon-1907

Pollock, J. (1950). Number 18 [Painting]. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY. United States.

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AWSS35953_35953_39580984

rutaloot. (2008, November 29). Woody Guthrie — This land is your land [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/wxiMrvDbq3s

Sargent, J. S. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew [Painting]. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/AIC_40038

Yeats, W. B. (May, 1914). A Coat. Poetry, a Magazine of Verse. IV.(11). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/12893/a-coat.

A term usually applied to short poems expressive of a poet's thoughts or feelings; as a broad genre, it includes such forms as the sonnet, ode, and elegy, along with many other varieties deriving from popular song. The term originally referred to a Greek song to be accompanied on the lyre, but later became associated with song‐like poems uttered by a single speaker.

A short rhyming lyric poem, usually of fourteen lines of iambic pentameter.

French term for a type, species, or class of composition with common conventions (“Genre”).

the social, cultural, and historical milieu in which a work of art is composed and received by an audience. Note that later audiences will respond from a different point of view and may struggle to understand the original context.

a “disinterested” attitude or way of experiencing objects independent of desires or any motivations to do with utility, economic value, moral judgement, or personal emotion. A concern with experiencing the object “for its own sake,” for example appreciating formal beauty (Jannaway).

French for dark cinema, a term coined by 1960s French film critics to describe films with dark themes and black and white film effects that strongly contrasted light and shadow. Characteristic of German Expressionism (1910s and 20s), Hollywood crime films (1930s and 1940s) and French post-war cinema (1940s and 50s).

paintings or other works depicting scenes from daily life. Often associated with the type of domestic subjects favored by 17th-century Dutch artists (Chivers “Genre Pieces” 2009).

a genre of painting, drawing, or photograph arranging inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, pottery or furniture, usually in an interior scene.

an established practice—whether in technique, style, structure, or subject-matter—commonly adopted in artistic works by customary agreement or precedent rather than by natural necessity (“Convention”).

an enthusiastic and highly informed admirer of the arts or of particular artists or genres.

Term that came into use in the 18th century to describe the ‘higher’ non-utilitarian arts, as opposed to applied or decorative arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture, and often extended poetry and music (Fine arts).

a general term referring to innovative, experimental, potentially subversive artistic movements that challenge the conventions of the day.

pattern of measured sound-units recurring more or less regularly in lines of verse (Meter). In English verse, a pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables: e.g. Jack Spratt could eat no fat//his wife could eat no lean.//And so betwixt them both, you see,//The licked the platter clean.

forms of expression that manipulate normal usage for rhetorical effect. Loosely divided into Tropes (plays of meaning) and Schemes (arrangements and patterns that enhance meaning).