V. Process and Organization

5.3 Drafting

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; Sarah M. Lacy; Melanie Gagich; and Terri Pantuso

Recall from Section 2.1 the six steps of the writing process:

- Understand the assignment

- Gather ideas and form a working thesis

- Write a draft

- Revise the draft(s)

- Proofread/edit the draft(s)

- Turn in the draft, receive feedback, and revise (if needed)

Now that you’ve decided on an organizational strategy for your essay, it’s time to begin the third step. Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing. Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have prewriting and planning already done, so you know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline or prewriting notes.

Goals and Strategies for Drafting

Your objective at this stage of the writing process is to draft an essay with at least three body paragraphs, which means that the essay will contain a minimum of five paragraphs, including an introduction and a conclusion. This five paragraph structure is sometimes referred to as the emphatic method. While the five paragraph format works well for beginning writers, you’ll want to move beyond this mold and think of your work in a more organic manner as you progress further along through the process.

Keep in mind that a draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. Another option might be to use the Notes feature on your smartphone.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

The following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about.

You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page. - Write one paragraph at a time and then stop.

As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines. - Take short breaks to refresh your mind.

This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multi-page report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write. - Be reasonable with your goals.

If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments. - Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write.

These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can. Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer), or on a post-it note. On that card/post-it, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

The Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in the previous sections step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft.

A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that grabs the audience’s interest, tells what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

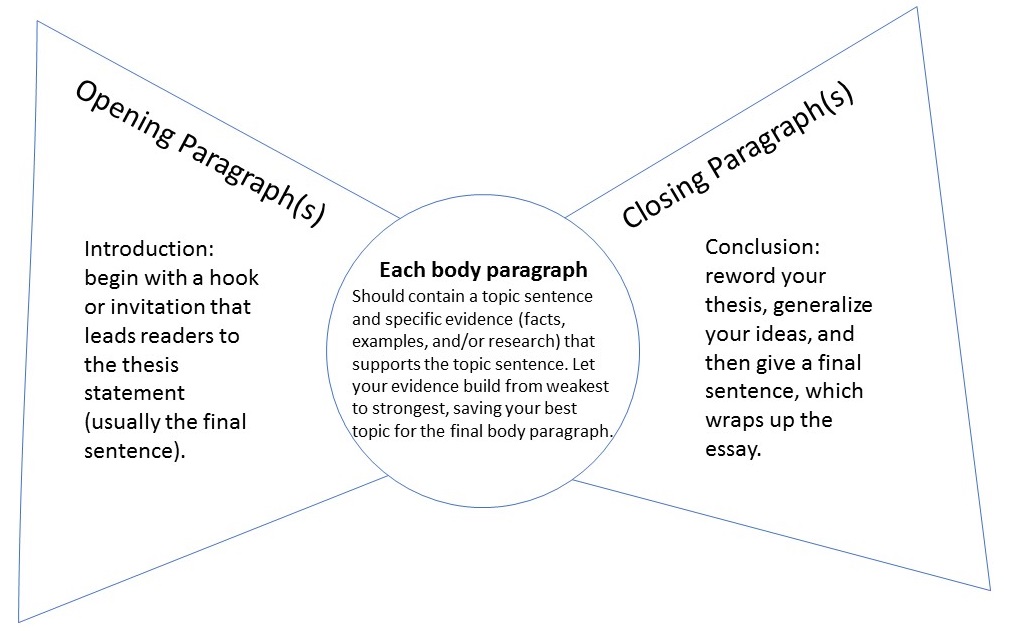

The Bowtie Method

There are many ways to think about the writing process as a whole. One way to imagine your essay is to see it like a bowtie. In Figure 5.3.1[1] below, you will find a visual representation of this metaphor. The left side of the bow is the introduction, which begins with a hook and ends with the thesis statement. In the center, you will find the body paragraphs, which grow with strength as the paper progresses, and each paragraph contains a supported topic sentence. On the right side, you will find the conclusion. Your conclusion should reword your thesis and then wrap up the paper with a summation, call to action, or challenge. In the end, your paper should present itself as a neat package, like a bowtie.

If you think of this method on its side, you might envision an hour-glass figure. In either visual, the concepts remain the same: start broad, narrow the focus, then extend back out to repeat the main idea.

Sample First Draft

Let’s follow Mariah as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. The following is Mariah’s thesis statement:

Mariah’s Thesis Statement

E-book readers are changing the way people read.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience:

Mariah’s Notes on Purpose and Audience

Everyone wants the newest and the best digital technology, but the choices are many, and the specifications are often confusing.

Purpose: My purpose is to inform readers about the wide variety of consumer digital technology available in stores and to explain why the specifications for these products, expressed in numbers that average consumers don’t understand, often cause bad or misinformed buying decisions.

Audience: My audience is my instructor and members of this class. Most of them are not heavy into technology except for the usual laptops, cell phones, and MP3 players, which are not topics I’m writing about. I’ll have to be as exact and precise as I can be when I explain possibly unfamiliar product specifications. At the same time, they’re more with it electronically than my grandparents’ VCR-flummoxed generation, so I won’t have to explain every last detail.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. Remember that she could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The Roman numeral I identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and Arabic numerals label sub-points.

Mariah’s Sentence Outline

- Ebook readers are changing the way people read.

- Ebook readers make books easy to access and to carry.

- Books can be downloaded electronically.

- Devices can store hundreds of books in memory.

- The market expands as a variety of companies enter it.

- Booksellers sell their own ebook readers.

- Electronics and computer companies also sell ebook readers.

- Current ebook readers have significant limitations.

- The devices are owned by different brands and may not be compatible.

- Few programs have been made to duplicate the way Americans borrow and read printed books.

- Ebook readers make books easy to access and to carry.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

Mariah’s Paragraph

Ebook readers are changing the way people read, or so ebook developers hope. The main selling point for these handheld devices, which are sort of the size of a paperback book, is that they make books easy to access and carry. Electronic versions of printed books can be downloaded online for a few bucks or directly from your cell phone. These devices can store hundreds of books in memory and, with text-to-speech features, can even read the texts. The market for ebooks and ebook readers keeps expanding as a lot of companies enter it. Online and traditional booksellers have been the first to market ebook readers to the public, but computer companies, especially the ones already involved in cell phone, online music, and notepad computer technology, have also entered the market. The problem for consumers, however, is which device to choose. Incompatibility is the norm.

Ebooks can be read only on the devices they were intended for. Furthermore, use is restricted by the same kind of DRM systems that restrict the copying of music and videos. So, book buyers are often unable to lend books to other readers, as they can with a traditional book. Few accommodations have been made to fit the other way Americans read: by borrowing books from libraries. What is a buyer to do?

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and document/essay with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that subfolder to store all of the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them. In your documents, observe any formatting requirements for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters that your instructor requires.

Drafting Body Paragraphs

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement. The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be relevant to the thesis.

Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your supporting points wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis. - Be specific.

The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be more specific than the thesis. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical. - Be detailed.

Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Pre-write to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you pre-write you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

As you developed a working thesis through prewriting techniques, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three very compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on, or a solid foundation for, your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; they add authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. There are many types of sources that you can use for your essays, such as newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field. The best source to use for your essay will depend on its topic and context; formal research papers will tend to rely more heavily on scholarly journal articles and books, while a movie review may be likely to cite a website such as Rotten Tomatoes. Regardless of your topic, it is important to use the best quality sources available – which may take some digging and even a visit or two to the library. When using sources, you are responsible for properly documenting the borrowed information properly. More information on source attribution and citation formatting is available in the Ethics section of this text (section VIII).

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations. Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements: topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read previously, topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your professor instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and basic essay assignments because it is meant to help students create fully developed essays. However, writers should maintain flexibility and not expect all essays to conform to that model. The emphasis should be on creating an essay that provides enough support to tell a story, create an image or idea, or inform or persuade the audience.

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence. The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement.

Example of Thesis and Supporting Details

Thesis: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Dogs can scare cyclists.

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the roads.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People walking at night freeze in fear.

- Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across streets create danger.

- Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

As previously discussed, you have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence. An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis.

Drafting Introductory and Concluding Paragraphs

Picture your introduction as a storefront window. You have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion). Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis). Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis statement.

Writing an Introduction

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- Establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject.

- Introduces the general topic of the essay.

- States the thesis that will be supported in the body paragraphs.

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to your essay. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing to read the essay.

Attracting Interest in Your Introductory Paragraph

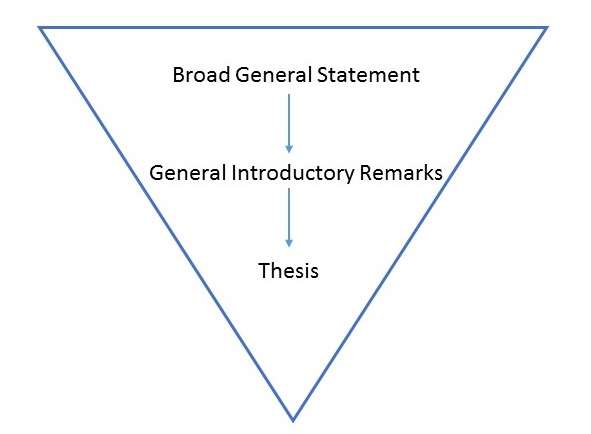

Your introduction should begin with an engaging statement devised to provoke your readers’ interest. In the next few sentences, introduce them to your topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement can be achieved using a funnel technique, as illustrated in Figure 5.3.2[2] below.

Immediately capturing your readers’ interest increases the chances of having them read what you are about to discuss. You can garner curiosity for your essay in a number of ways. Try to get your readers personally involved by doing any of the following:

- Appealing to their emotions;

- Using logic;

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion;

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact;

- Raising a question or series of questions;

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay;

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident;

- Opening with a striking image;

- Including a personal anecdote.

Remember that your diction, or word choice, while always important, is most crucial in your introductory paragraph. Boring diction could extinguish any desire a person might have to read through your discussion. Choose words that create images or express action.

Earlier in this section we followed Mariah as she moved through the writing process. In this section, Mariah writes her introduction and conclusion for the same essay on media. Mariah incorporates some of the introductory elements into her introductory paragraph, which she previously outlined. Her thesis statement is underlined.

Mariah’s Introductory Paragraph

Play Atari on a General Electric brand television set? Maybe watch Dynasty? Or read old newspaper articles on microfiche at the library? Thirty-five years ago, the average college student did not have many options when it came to entertainment in the form of technology. Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and the digital age has revolutionized the way people entertain themselves. In today’s rapidly evolving world of digital technology, consumers are bombarded with endless options for how they do most everything, from buying and reading books to taking and developing photographs. In a society that is obsessed with digital means of entertainment, it is easy for the average person to become baffled. Everyone wants the newest and best digital technology, but the choices are many and the specifications are often confusing.

Writing a Conclusion

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may run out of energy. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as in the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay. However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

The Anatomy of a Strong Conclusion

Keep in mind that the ideas in your conclusion must conform to the rest of your essay. In order to tie these components together, restate your thesis at the beginning of your conclusion. This helps you assemble, in an orderly fashion, all the information you have explained in the body. Repeating your thesis reminds your readers of the major arguments you have been trying to prove and also indicates that your essay is drawing to a close. A strong conclusion also reviews your main points and emphasizes the importance of the topic.

The construction of the conclusion is similar to the introduction in which you make general introductory statements and then present your thesis. The difference is that in the conclusion you first paraphrase, or state in different words, your thesis and then follow up with general concluding remarks. These sentences should progressively broaden the focus of your thesis and maneuver your readers out of the essay.

Many writers like to end their essays with a final emphatic statement. This strong closing statement will cause your readers to continue thinking about the implications of your essay; it will make your conclusion, and thus your essay, more memorable.

Another powerful technique is to challenge your readers to make a change in either their thoughts or their actions. Challenging your readers to see the subject through new eyes is a powerful way to ease yourself and your readers out of the essay.

When closing your essay, do not expressly state that you are drawing to a close. Relying on statements such as in conclusion, it is clear that, as you can see, or in summation is unnecessary and can be considered trite.

It is wise to avoid doing any of the following in your conclusion:

- Introducing new material.

Introducing new material in your conclusion has an unsettling effect on your reader. When you raise new points, you make your reader want more information which you could not possibly provide in the limited space of your final paragraph. - Contradicting your thesis.

Contradicting or changing your thesis statement causes your readers to think that you do not actually have a conviction about your topic. After all, you have spent several paragraphs adhering to a specific point of view. - Changing your thesis.

When you change sides or open up your point of view in the conclusion, your reader becomes less inclined to believe your original argument. - Using apologies or disclaimers.

By apologizing for your opinion or stating that you know it is tough to digest, you are in fact admitting that even you know what you have discussed is irrelevant or unconvincing. You do not want your readers to feel this way. Effective writers stand by their thesis statement and do not stray from it.

Mariah incorporates some of these pointers into her conclusion. She has paraphrased her thesis statement in the first sentence, which is underlined.

Mariah’s Conclusion

In a society fixated on the latest and smartest digital technology, a consumer can easily become confused by the countless options and specifications. The ever-changing state of digital technology challenges consumers with its updates and add-ons and expanding markets and incompatible formats and restrictions – a fact that is complicated by salesmen who want to sell them anything. In a world that is increasingly driven by instant gratification, it’s easy for people to buy the first thing they see. The solution for many people should be to avoid buying on impulse. Consumers should think about what they really need, not what is advertised.

Make sure your essay is balanced by not having an excessively long or short introduction or conclusion. Check that they match each other in length as closely as possible, and try to mirror the formula you used in each. Parallelism strengthens the message of your essay.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph which you will read later. She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Mariah’s Title

Thesis Statement:

Some people want the newest and the best gaming technology, but the choices are many, and the specifications are often confusing.

Working Title:

Gaming Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition. 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Lacey, Sarah M., and Melanie Gagich. “The Writing Process.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/3-1-eng-100-101-writing-process/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- “Bowtie Method” was derived by Brandi Gomez from “Figure of the Bowtie Method” in: Kathryn Crowther et al., Successful College Composition, 2nd ed., Book 8 (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

- “Funnel Technique” was derived by Brandi Gomez in 2019 from “Fig. Funnel Technique” in: Kathryn Crowther et al., Successful College Composition, 2nd ed., Book 8 (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses.

A short account or telling of an incident or story, either personal or historical; anecdotal evidence is frequently found in the form of a personal experience rather than objective data or widespread occurrence.

A figure of speech that involves an implied or indirect comparison between two things that are not similar. For example, “you are my sunshine” is a metaphor.

Usually the first sentence or portion of a text that is meant to capture the reader’s attention and keep them interested in reading.

A form of an analysis that involves original thought, explanation, or critique about an observation made by a commentator (writer, speaker, or other content creator).

A strong expression or emphasis either in speech, writing, or action.

To hint at, insinuate, imply, or suggest. An allusion is a direct or indirect reference that is well-known by the majority of the public. For example, “We are not in Kansas anymore” is an allusion to The Wizard of Oz.