III. Rhetorical Situation

3.12 Visual Analysis in Composition & Rhetoric and Literature

James Francis Jr.

In this section, we’ll focus on how visual analysis functions within the composition classroom and life outside of that space. To simplify our discussion, we will consider a visual text as one that tells a story or makes a persuasive argument through its form and content without a leading or major focus on the written word. Three questions will guide this unit to help provide a better understanding of visual analysis toward its effective use in writing:

- What is a visual analysis?

- Why is visual analysis important?

- How can we use visual analysis in the composition & rhetoric and literature classrooms?

What is Visual Analysis?

In the simplest understanding, visual analysis is the action of analyzing visuals to comprehend the messages they communicate to various audiences. However, a more complex investigation of the process involves a breakdown into visual rhetoric and visual literacy – the act of communicating through visuals and the ability to “read” them, respectively. In other words, visuals are composed of elements like color, shape, space, texture, shading, and positioning that convey specific messages and meaning based on the arrangement of the elements working together and their individual impact. How we “read” (interpret) them depends on subjective perspectives that we back up by using the text itself to support our analysis. Let’s take a look at an example in Figure 3.12.1.[1]

By reading the elements of this photograph in Figure 3.12.1 – without any other context provided – we might come to the following conclusions:

- The photograph represents a protest.

- The people pictured are angry/upset about an issue.

- The people are united in their objective.

- This is a public demonstration.

- The situation is immediate.

How can we make these interpretations?

- The image depicts a gathering of people with fists raised high in a symbolic protest gesture.

- Their mouths are open, indicating voices yelling for recognition.

- The flags carried by the people are all the same color.

- There is a police presence in the background, typically to provide public oversight.

- The photo is framed in closeup which provides an urgent mood/tone.

This type of reading is something we do every day as we interpret traffic lights while driving, say hello to a stranger on the sidewalk based on their facial expression, and binge-watch a favorite TV series into the wee hours of the morning, following visual cues provided in each episode.

Exercise

Activity: Discuss the following image (Figure 3.12.2[2]) with your peers to compare similar and different ways in which you interpret its visual elements:

But if you read visuals all the time, you might not immediately consider their importance as writing tools in composition & rhetoric and literature.

Why is Visual Analysis Important?

Because we read visuals all the time is the exact reason why visual analysis is important. We need to know how to understand visuals because they represent such large components of life: human communication, learning how-to do something, and entertainment; and within the classroom, they function as aids to help us develop critical reading, writing, and comprehension skills that can be applied to various modes of writing.

How Can We Use Visual Analysis in the Composition & Rhetoric and Literature Classrooms?

First, we must remember that literature is written and visual. We encounter stories in the form of poems, short fiction, novellas/novels, screenplays, and stage plays. But stories are also told on the small screen (television) and big screen (cinematic shorts and feature-length movies). In both composition & rhetoric and literature courses, we are sometimes provided a visual text to examine. When prompted to engage in the writing process, your instructor might ask you to write a:

- Review/Evaluation

- A movie review is comparable to a book review. Your argument centers on the personal evaluation of the film (what you like, dislike, or other and why) and takes into account literary/film elements that support your claim. What separates the book and movie review is simply the medium, the format of film as a visual narrative instead of a written narrative. As a movie, elements that relate to the visuals – cinematography, camera shots, framing, montage, set and costume design – are often given priority to discuss how they contribute to the favorable and/or negative review. For a more detailed list of written and visual literature terminology, see the Visual Terminology chart later in this section.

Sample Thesis

The Blair Witch Project[3] uses shaky camera angles and dark settings to successfully convey a sense of dread as a classic modern horror film.

- Reflection

- Watching a TV series or film allows you, the viewer, to compare your own lives with characters and situations represented in the narrative. An introspective discussion forms to demonstrate your personal relatability to, or disconnection from, the story. The reflection also offers the writer a chance to discuss how the narrative content of the series/film offers relevant social commentary. For example, Spike Jonze’s Her[4] makes real-world associations regarding our use or misuse of technology to communicate with each other.

- Rhetorical Analysis

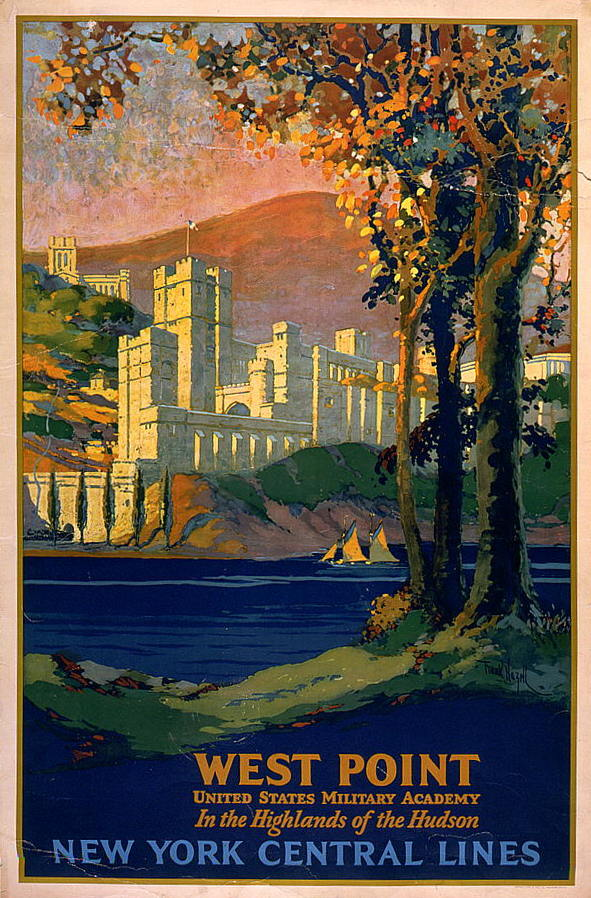

- The writing could involve examining an advertisement, commercial, or marketing campaign to demonstrate how design principles (the CRAP test – contrast, repetition, alignment, proximity), use of color, and font choice indicate uses of ethos, pathos, and/or logos to effectively communicate a message and persuade the viewer. Figure 3.12.3[5] is an example.

Example of Rhetorical Analysis

The soft and warm autumn colors of the natural environment (trees, land, and water) in Figure 3.12.3 contrast the hard and cold building material of West Point to create a welcoming atmosphere. We see the poster like an advertisement for a vacation spot more than a military academy: repetition bonds the environment to the academy, as the blue and orange (primary and secondary) color scheme of the setting also appears in the text; center-alignment pulls focus directly to West Point; and the academy exists in close proximity to the natural elements to persuade the viewer to consider it in a similar perspective – natural.

The poster creates an emotional connection with its audience, particularly people who may be on the fence regarding military service and/or individuals who never considered it as a possibility. It is cohesive in its message and persuasive as it appeals to the viewer’s desire to connect with nature in a picturesque location. The sailboats convey a sense of tranquility, and the academy resembles a regal castle nestled in a fairy tale landscape. We are convinced that even if we never thought about joining the military, doesn’t West Point seem like a great place to start if we make that life decision?

- Analysis/Critique

- Literary analysis and film criticism function in the same manner – unlike the review – to examine the text (story) in order to argue what the narrative form and/or content communicate to its audience. This is typically accomplished by examining story structure, use of literary & film devices; critical theory can also be applied to “read” the text through various lenses of criticism (feminist, critical race theory, Marxist, disability studies, cultural/new historicist, queer theory, gender studies, structuralist). Visual story elements are analyzed and criticism is applied to the text to unpack various arguments presented in the narrative.

- Art criticism represents another extension of visual analysis in which you might study a painting, photograph, sculpture, installation, drawing, or other medium to interpret what the artist’s work represents – what they are communicating to their audience through the art text.

- Research

- The previous section on analysis/critique involves conducting research; however, research writing might also focus on a visual text in an informative manner: providing historical and cultural context, investigating development, offering description and/or definition, reporting findings, and more. In this respect, the visual text is the site of investigation and sometimes a prompt for the writing exercise. You might research the production history of Inception[6] or use the film to research a topic presented within it, such as lucid dreaming.

What unifies these various types of writing is that you offer persuasive arguments for your audience to consider, and supporting evidence (most often secondary source material) is used to develop the conversation and validate your claims. Visuals are used as primary sources for evaluation and/or prompts to help illustrate or provide a rhetorical situation to investigate. Although visual analysis has been covered in a few different ways in this section, always consult your instructor and/or your assignment sheet guidelines if you are unsure how visuals are being used in your course and what the expectations are for how you engage with them.

*** The elements/terms mentioned in the various types of visual texts identified above are not exhaustive. For a more comprehensive listing, try performing “soft” research in which you utilize services such as Google or Wikipedia to obtain more information regarding the specific medium.

Visual Terminology

Written and visual texts share a lot in common regarding the elements that comprise their narratives and how we interpret them, but there are terms that distinguish the two from each other. The following "Written Literature Terminology" list (Table 3.12.1) identifies select terminology for written literature that also apply to visual narratives, but not vice versa. The subsequent "Visual Literature Terminology" list (Table 3.12.2) identifies select terminology that is applicable to visual narratives only.

| Written Literature Terminology | ||

|---|---|---|

| antagonist | flat (static) character | realism |

| antihero | foreshadowing | resolution |

| author | genre | rhetoric |

| chapter | implicit meaning (subtext) | rising action |

| character | interior monologue | round (dynamic) character |

| characterization | irony | scene |

| climax | metaphor | setting |

| conflict | motif | simile |

| dénouement | narration | story |

| dialogue | narrator | subplot |

| dramatic irony | omniscient | theme |

| explicit meaning | plot | verisimilitude |

| flashback | point of view (POV) | |

| flash-forward | protagonist | |

Table 3.12.1. Written Literature Terminology

| Visual Literature Terminology | ||

|---|---|---|

| aerial-view shot | depth of field | method acting |

| angle | diegesis | mise-en-scѐne |

| animation | direct narration (breaking the 4th wall) | montage |

| auteur / auteurism | director | production value |

| blockbuster | dissolve | rule of thirds |

| cameo | documentary | score |

| camera oscura | dolly shot | shot |

| casting | editing | slow motion |

| CGI | establishing shot | special effects |

| character POV | experimental films | split screen |

| cinematic time | extra | starpower |

| cinematography | fade-in/fade-out | tracking shot |

| cinéma vérité | film noir | two-shot |

| close-up | Foley sound | typecasting |

| continuity editing | graphic match cut | voice-over narration |

| costumes | improvisation | |

Table 3.12.2. Visual Literature Terminology

- Derek Blackadder, Bangladeshi Spectrum Workers Protest Deaths, May 29, 2005, photograph, Flickr, accessed January 6, 2021, https://www.flickr.com/photos/39749009@N00/16231675. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License. ↵

- Jorge González, Traffic Lights, April 22, 2006, photograph, Flickr, accessed January 6, 2021, https://www.flickr.com/photos/35873968@N00/134769430. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License. ↵

- The Blair Witch Project, directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez (Santa Monica, CA: Artisan Entertainment, 1999). ↵

- Her, directed by Spike Jones (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 2013.) ↵

- Frank Hazell, West Point, United States Military Academy, in the Highlands of the Hudson. New York Central Lines - Frank Hazell. LCCN94504463 (Cropped).jpg. circa 1920s, Wikimedia Commons, accessed January 6, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:West_Point,_United_States_Military_Academy,_in_the_highlands_of_the_Hudson._New_York_Central_Lines_-_Frank_Hazell._LCCN94504463_(cropped).jpg. ↵

- Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 2010). ↵

To take the position or side of the subject (rather than the object) which is the one doing the observing (rather than being observed); the belief, preference, or understanding of an individual.

To reflect or think on one’s self, being, mental, physical, or emotional state insightfully or analytically.

To be close to, next to, or adjacent to; nearness or closeness.