2.2 The Process of Becoming an Entrepreneur

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the evolution of entrepreneurship through American historical periods

- Understand the nine stages of the entrepreneurial life cycle

Scholars of business and entrepreneurship have long debated how people become entrepreneurs. Are entrepreneurs born or made? That is, are some people born with the natural skills, talent, and temperament to pursue entrepreneurship? Or can you develop entrepreneurship skills through training, education, and experience? These questions reflect the classic debates known as “nature versus nurture” or “born versus made,” which attempt to explain the determinants of a person’s personality and character.

This debate has been around for centuries. In classical Greece, Plato supported the nature argument, whereas Aristotle believed in the nurture perspective. During the eighteenth-century Enlightenment period, Immanuel Kant (1724–1824; supported the supremacy of human reason) and John Locke (1632–1704; opposed authoritarianism) argued their views. Kant firmly believed that obedience was the expected and desired behavior, whereas Locke believed in allowing some degree of freedom and creativity. The focus of the aspects of this argument changed when late-nineteenth-century psychologists sought to understand how individuals obtain knowledge, and as modern psychologists concentrated on additional factors such as intelligence, personality, and mental illness.

Scott Shane, a professor of entrepreneurial studies at Case Western Reserve University, codirected a study using identical twins and fraternal twins as the research subjects. Shane determined that entrepreneurs are about 40 percent born and 60 percent made, meaning that nature—that is, an individual’s DNA—is responsible for 40 percent of entrepreneurial behaviors, whereas nurture is responsible for about 60 percent of entrepreneurial behaviors.[1] Although “nature versus nurture” and “born versus made” are parallel arguments, researchers and experienced entrepreneurs suggest a combined viewpoint. You can unite your natural talents and abilities with training and development to achieve a well-rounded entrepreneurial experience and outcome. Once you determine that entrepreneurship is in your future, the next action is to establish a process to follow, such as identifying useful reading materials, attending classes or workshops, finding a mentor, or learning by doing through simulations or firsthand experiences. Firsthand experiences occur throughout our days and lives as we gain relevant experiences and as we develop a mindset to seek out opportunity-recognition behaviors. Completing coursework, such as reading this textbook, and reviewing the suggested resources provided within this textbook are actions that can support your knowledge and awareness of entrepreneurship as a valid option for your future.

Exercise – Entrepreneurial Personality Test

Review Bill Wagner’s article “What’s Your Entrepreneurial Personality Type?” in Entrepreneur .

Then, go to The Entrepreneur Next Door at to take the Entrepreneurial Personality Test to find your personality type.

- Think about your results. Are you a generalist or a specialist?

- Once you know this information, what other entrepreneurial personality types do you fit into?

- How can you use this information in your pursuits as an entrepreneur?

- What does this information tell you about selecting members of your startup team?

Historical Perspective

The evolution of entrepreneurship in the United States has spanned centuries. Entrepreneurs have responded to and innovated within the political and economic conditions of their times. The United States’ economic and industrial spirit has inspired generations of entrepreneurial Americans. Understanding this history might help you appreciate the importance of entrepreneurship as you consider your own entrepreneurial journey.

During the late 1700s, the Pembina Band of Chippewa lived along the Red River of the North, which flows through North Dakota and Minnesota, and into Canada. European explorers established trading posts in this region and bargained with the Pembina and others for pemmican, a buffalo or fish jerky created by tribes for survival during harsh winters when food was scarce. The Pembina pemmican was exported internationally through trading with French, Canadian, British, and other explorers.[2] The Pembina solved a problem of food scarcity, then leveraged the product to trade for other products they needed that were available through the trading posts.

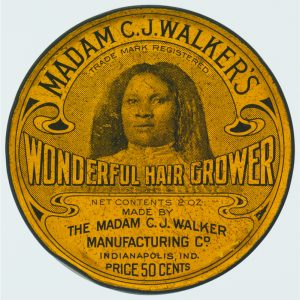

In the late 1880s, Madam C. J. Walker, an African American hair-care entrepreneur, developed and marketed her products across the United States (Figure 2.12), hiring sales agents and founding the Madam C. J. Walker Hair Culturists Union of America and the National Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers Association in 1917.[3] She started her company with a philosophy of “hair culture,” which quickly became popular and eventually led to steady employment for African American women. Another African American, Charles Drew, established the national blood bank in the late 1930s, just before World War II gave rise to the need for quick access to blood.[4] He researched transfusion medicine and saw a need that he wanted to fulfill. Drew applied the ideas from his doctoral thesis to create the blood bank and continued to innovate, developing mobile blood donation stations.

Colonial and Early America: 1607–1776

The earliest concept of an “entrepreneur” can be traced to this era, from the French entreprendre, which translates as “to do something” or “to undertake.”[5] Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832), a French philosopher, economist, and businessman, supported lifting restraints to encourage business growth, a highly liberal view in the late 1700s. “The entrepreneur shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield,” is a concept attributed to Say, as is the word entrepreneur.[6]

Entrepreneurial-minded persons included merchants, landowners, manufacturers in textile-related trades, shipbuilders, explorers, merchants, and world market traders.[7] The first immigrants to the British colonies took advantage of several key inventions developed before this era, such as printing, double-entry bookkeeping, and improvements in ship design and navigational instruments. The first North American patent was granted in 1641 by the Massachusetts General Court to Samuel Winslow for a new process for making salt. The entrepreneurial spirit of the early colonists helped shape an economic landscape that lasted for generations. Some notable pioneering inventors and entrepreneurs are shown in Table 2.2 and (Figure 2.13).

Notable Early US Inventors and Entrepreneurs

| Inventor or Entrepreneur | Contribution(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pierre-Esprit Radisson (1640–1710), French explorer | Founded Hudson’s Bay trading company | Offered bartering of furs for textiles and guns |

| William Penn (1644–1718), colonist | Founded Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as a sanctuary for Quakers | Early social entrepreneur |

| Sybilla Masters (1676–1720), inventor | Invented method to clean and refine corn grown by early settlers | Patent for a process for cleaning and milling corn (1715) |

| Thomas Hancock (1703–1764), merchant | Founded trading house that furnished multiple goods | Sought alternative funding sources to finance business interests |

| Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), inventor, publisher, statesman | Established printing franchises and an infrastructure for his apprentices to launch in other colonies | Epitome of an inventor and serial entrepreneur |

As entrepreneurship flourished in the American colonies, the economic structure also began to emerge. The prevailing view of economics was associated with the stockpiling of gold and silver. Colonists perceived imports as a reduction of metal wealth—gold and silver money—and felt that exports channeled these metals back to the colonies. To categorize the economic mindset of the time, the Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith (1723–1790) wrote An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). This influential treatise outlined the concepts of free trade and economic expansion through capitalism, a system in which individuals, people, and companies have the freedom to make decisions and own property as well as benefit from their own efforts, with government playing a secondary role in oversight. This book confirmed Smith as the “father of economics” and modern free trade. Among the most significant concepts that Smith proposed were the “invisible hand” theory of supply and demand in the marketplace; the use of the GDP to measure a country’s level of production and commerce; and the self-interest concept, whereby individuals inadvertently help others as they pursue their own goals.[8] The ability to gain personally from entrepreneurial activities is a key factor in supporting entrepreneurial behavior. Smith’s concepts continue to influence modern economics and entrepreneurial activity.

The First Industrial Revolution: 1776–1865

As the colonies expanded, so did opportunities and interest in property ownership, manufacturing, inventions, and innovations. An innovation is any new idea, process, or product, or a change to an existing product or process. The understanding and acceptance of innovation developed around 1730, when the economist Richard Cantillon identified the first academic meaning and characteristics of “entrepreneurship” as the “willingness to bear the personal financial risk of a business venture.”[9] The First Industrial Revolution was notable for the explosion of inventive activities by the “great inventors,” who pursued entrepreneurial opportunities to meet market needs, demands, and economic incentives.[10]

An important thing to keep in mind is that dates of inventions don’t necessarily reflect specific launch dates. Development of these inventions may have been ongoing for years or decades before they were considered market-viable products.

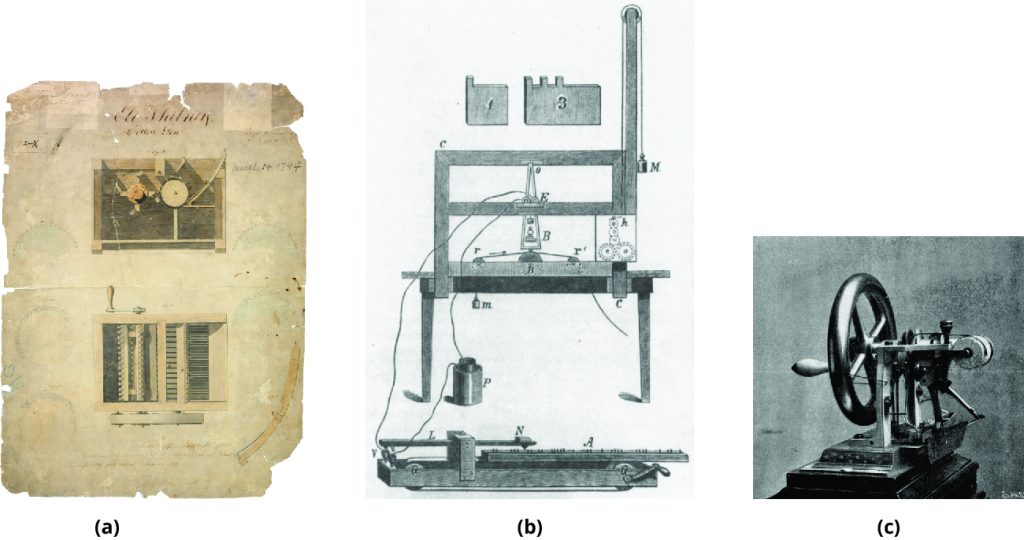

A plethora of inventors and their inventions transformed several industries and economic classes across the growing nation. During this era, the country benefited from inventions that created, expanded, or revolutionized industry and increased wealth and expansion. These revolutionary inventors included Eli Whitney (cotton gin, 1794), Elias Howe (sewing machine, 1845), and Samuel Morse (telegraph, 1830s–1840s) (Figure 2.14). Many other people contributed to these and other inventions.

Although he was not an inventor but an industrialist, Andrew Carnegie provides an interesting example. A manufacturer who focused on the value of innovations and how to implement them, Carnegie adopted newly developed techniques to improve steel production. He also was among the first to implement vertical integration, the strategy of gaining control over suppliers of raw materials and distributors of finished products to expand or control the relevant supply chain. He developed a reliable network of suppliers and distributors to support his steel factories. Carnegie also was one of the first magnates to practice philanthropy. He gave away much of his immense fortune to support community and public library systems, concert halls, museums, and scientific research.[11]

These entrepreneurial pioneers, and many others like them, sought ways to earn a return on investment on an invention and to protect themselves legally through the patent process. A patent is a legal grant of protection for an inventor over the rights, usage, and commercialization of an invention for a set time period.[12] An early US patent was issued in 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for his process of making potash as a fertilizer ingredient.[13]

The innovations of women, African Americans (enslaved or free persons), and other marginalized groups were crucial during this era. As we saw earlier, Sybilla Masters invented a method for grinding corn. She received a patent from the English king in 1715. But because women were not allowed to file for patents or even to own property at that time, the patent was filed in her husband’s name.[14] Although the invention of the cotton gin is attributed to Eli Whitney, as we have seen, it may have been based on a design by enslaved African Americans. Social and legal discrimination could limit or conceal the identities of actual inventors, especially if they were women or slaves.[15] Most patent applicants and awardees were White men. One exception was Mary Dixon Kies, who in 1809 became the first woman awarded a patent for her process of weaving straw with silk or thread. This was a key innovation for the hat industry, due to an embargo on European goods.[16] Likewise, many enslaved people were extremely innovative, but laws and prejudice prevented them from filing independently for patents. Because enslaved people had no rights, many sought patent submissions under their owners’ names but received no recognition or compensation for their efforts.[17] It was not until 1820 that an African American, Thomas Jennings, was granted a patent for a process called “dry scouring” for cleaning fabric.[18] As the successes and failures of inventors and innovations expanded, so did the consumer demand for better-performing products and services. This led to the Second Industrial Revolution.

The Second Industrial Revolution: 1865–1920

Although the First Industrial Revolution had a broad scope and a transformative impact, the Second Industrial Revolution helped shape consumer demand for the latest inventions and innovations developed by small and large businesses. The breakthroughs of this era brought applicable innovations in many fields, from chemistry to engineering to medicine.[19]

The nineteenth-century economists Jean-Baptiste Say and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) refined and popularized Cantillion’s definition of an entrepreneur to capture the spirit of their era. Their definition of “entrepreneur” describes someone who creates value by effectively managing resources for better productivity, and someone who is a financial risk taker.[20]

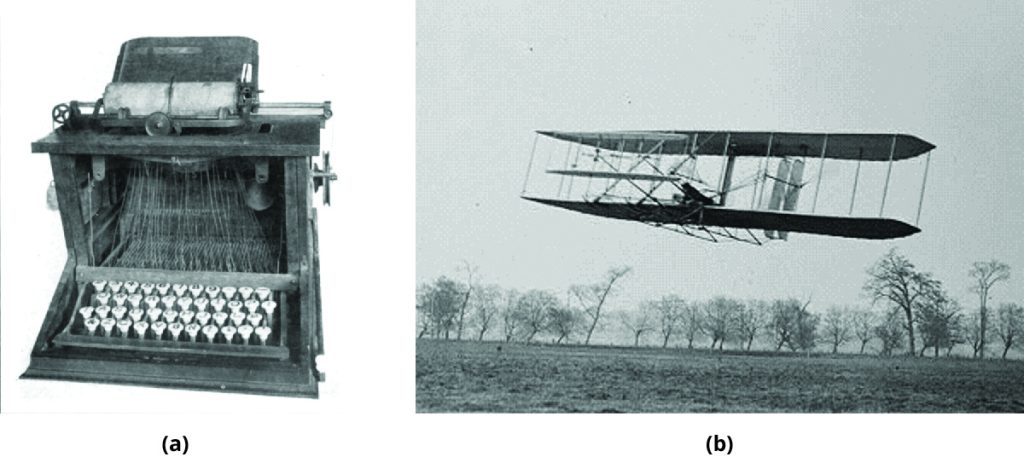

After the US Civil War and into the 1870s, many industries flourished with improvements in production organization (petroleum refinery storage, mass production) and technological systems (electricity and the telephone). Additional inventions included improvements in steel production, chemical dyes, transportation (diesel and gasoline engines, the airplane), assembly-line production, agriculture and food-processing improvements (refrigeration), textiles, and the typewriter (Figure 2.15).[21] As entrepreneurial activity, economic prosperity, and productivity demands increased, entrepreneurs and their inventions were highly regarded and sought after, contributing to the belief that the United States was a land of opportunity.

Interwar and Postwar America: 1920–1975

When World War I began, the US economy was in a recession, with Europeans purchasing US materials for the war. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, an economic boom ensued. Unemployment declined from 7.9 percent in 1914 to 1.4 percent in 1918 as the United States produced goods and equipment necessary to support the war efforts of the nation and its allies.[22] From an entrepreneurial perspective, World War I contributed to military-related advancements, communication equipment, and improvements in production processes. The American economic landscape began to shift during this era from small independent companies to big corporations. The smaller businesses in the previous era either dissolved or were absorbed by larger corporations. As the stock market crash of October 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s struck worldwide, innovation slowed. Consumer confidence waned as economic confidence and production declined, and unemployment rose.

Link to Learning

Visit the History site on the Great Depression or PBS’s American Experience article on the Great Depression to understand the background and circumstances that led to the stock market crash of 1929, the Great Depression, and how the United States rebounded during this period.

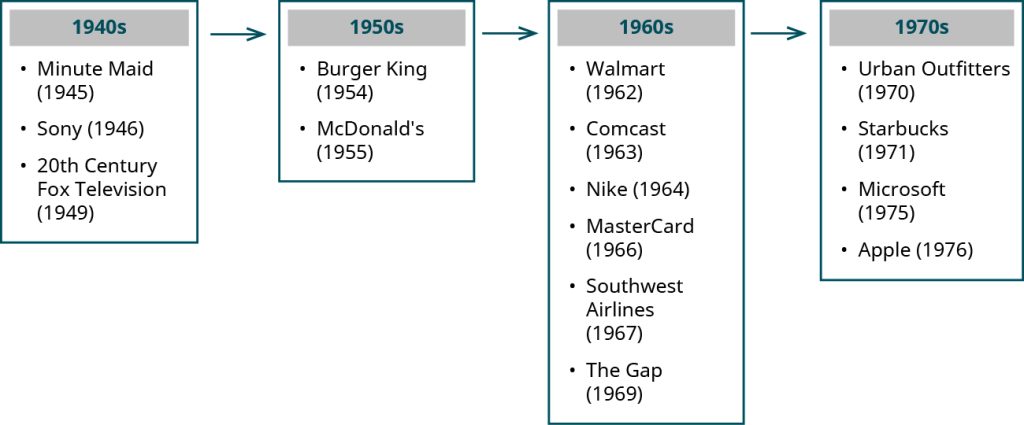

After World War II ended in 1945, American society shifted from reliance on the traditional entrepreneur as a resource to reliance on large organizations that offered stability and job security. Corporations continued to buy up small firms to standardize innovative, large-scale mass production of goods, services, and jobs. The idea of being an entrepreneur gave way to the idea of the “corporate man” with job security and health benefits offered by big employers. Although entrepreneurship did not totally vanish, its growth slowed tremendously compared with previous years and shifted to corporate entrepreneurship, whereby large corporations funded the development of new ideas, opportunities, or ventures through formal research and development processes that focused on the corporations’ own strategies and goals. Figure 2.16 lists some of the corporations that emerged during this period.

As economic views and confidence in how the United States might regain economic prosperity shifted, so did the scholarly meaning of entrepreneurship. One scholar and economist, Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950), introduced theories and terminology that continue to influence modern entrepreneurial concepts and practices. He originated two critical phrases: entrepreneurial spirit, which is associated with those individuals who are productive self-starters and make things happen, and creative destruction, which he defined as the “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”[23] Schumpeter’s theory that innovation would destroy established corporations to create new ones was not a popularly held or shared view at the time. The thought leaders of this era had different approaches to addressing the rise of corporations as part of the entrepreneurial fabric of the United States. Schumpeter theorized that corporations were better positioned than individuals to support the kinds of research and development that would result in innovations and have economic impact.[24] To complement this view, he also proposed the concept that corporate support of entrepreneurs’ visions would result in a sustainable “capitalistic financial system” to support and expand on the free-market system espoused by Adam Smith.[25] In contrast, the sociologist and journalist William Whyte (1917–1999) argued that entrepreneurial culture had changed because “American business life had abandoned the old virtues of self-reliance and entrepreneurship in favor of a bureaucratic ‘social ethic’ of loyalty, security and ‘belongingness.’”[26]

Finally, it is critical to note that the growth of corporations and opportunities expanded beyond the borders of the United States. Corporations faced novel global experiences that supported Schumpeter’s creative destruction theory, as other countries presented new dynamics to address. The annually created Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report is a scholarly examination that examines how a group of nineteen countries benefited from venture-capital investments and the factors affecting those investments for entrepreneurial activity. This study addressed the question of entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurial capacity, and entrepreneurial motivation as parts of the engagement within all industries and the direct correlation between venture-capital investment and high-growth startups.[27] The GEM report is created annually with timely and relevant information related to entrepreneurship and is available at this website: https://www.gemconsortium.org/. This cultural shift in the American entrepreneurial spirit generated new interest in the training and education of workers, ushering in the knowledge economy.

The Knowledge Economy: 1975 to Today

In the mid-1970s, the promises of corporate life began to lose their appeal to entrepreneurial-minded individuals. One change was established corporations’ shift in focus on innovations from research and development departments to internal entrepreneurial activities by intrapreneurs. An intrapreneur is an employee who acts as an entrepreneur within an organization, rather than going solo. Intrapreneurs contribute entrepreneurial ideas, products, and services, using corporate work time and resources, but on a much less formal basis than past corporate contributions to innovation. Quickly evolving advances in technology have touched every industry, and people with tech know-how have become champions. Firms dominating the technological landscape include Apple, Microsoft, 3M, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), IBM, and Oracle. In today’s David-versus-Goliath culture, these companies once were small startups, but now they command seemingly endless resources. New opportunities have arisen in the world of technology for those willing and able to compete with these giants. All companies, large and small, are interested in a more informed and educated workforce with specialized or advanced degrees in entrepreneurship and business administration. The new entrepreneurs are prepared to develop and lead firms that can become startup superstars. Viewed through our current lens, companies like Apple, Microsoft, Google, and others have become the new Goliaths, but in their startup days, these companies were the disruptors that fought to create new industries or reshape previously established ones.

The Entrepreneurial Process

Your approach to the entrepreneurial process, or the set of decisions and actions that you might follow (as in Figure 2.17) as a guide to developing or adjusting your venture, is fluid, not static. This is because your personal interests, background, experiences, resources, and connections are unique to you—but those areas may change over time. For instance, you and a friend might take an art class together for fun and both discover a hidden talent and eye for creating handcrafted jewelry that everyone loves. One day over lunch, you share some of your frustrations with your friend about an interest in potentially selling your unique creations to a local art gallery. Despite your research, you have few clues about where to start or how to get your art shown in a gallery. During your conversation, you are surprised to learn that your friend has already sold several pieces by following a mentor’s advice. Through several referrals, she figured out that her best option was to create a presence on Etsy, an artisan-focused website for e-commerce, electronic transactions, particularly over the Internet, for the exchange of goods and services. Even though you both started at the same place with similar goals, your results differed because you followed different entrepreneurial pathways. In this case, your friend decided to enter the entrepreneurial process at a different stage than you did. This type of scenario occurs every day and clarifies why ventures differ: The decisions of the entrepreneur or the entrepreneurial team are the heart and success of the venture. Why the entrepreneur is the most crucial resource for a venture will be discussed in more detail in later chapters.

If you decide to take the leap into entrepreneurship, you should follow a certain process before you launch your venture. What is that process? As we discussed previously in the steps of the entrepreneurial journey, you need to think through your goals, prepare and follow an action plan, make sound decisions and adjustments along the way, and persevere through challenges and crises to ensure a successful journey. If that sounds like you have some work to do, you are correct. However, if you follow or recognize the stages in the journey and keep track of the related elements, it could be the most satisfying work of your career. Many people find the entrepreneurial journey fulfilling, in part because they get to define their own paths. The plan to graduate, then find a career working hard to help a company or organization reach its goals, are even more satisfying when you can work for yourself to create your own path and purpose in the world.

Before you create your path, a key action in the entrepreneurial process is developing your entrepreneurial mindset. Recall that an entrepreneurial mindset is about being open, self-reflective, and honest about what you are willing to do and capable of doing to achieve success. For instance, are you comfortable with making sacrifices like spending an evening doing research instead of hanging out with friends or family?

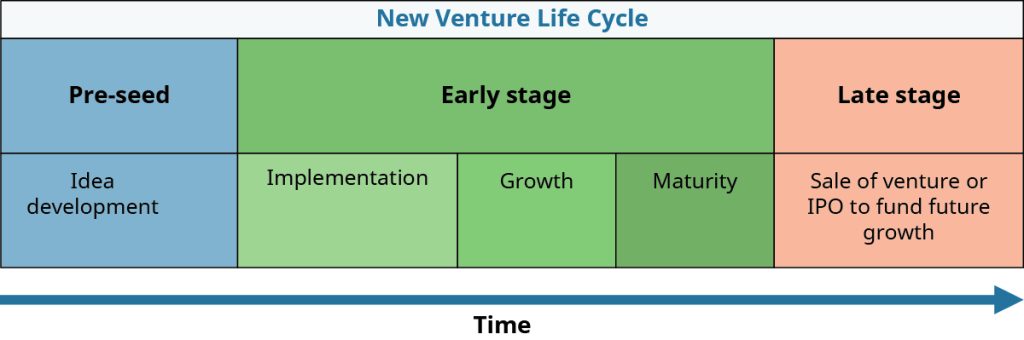

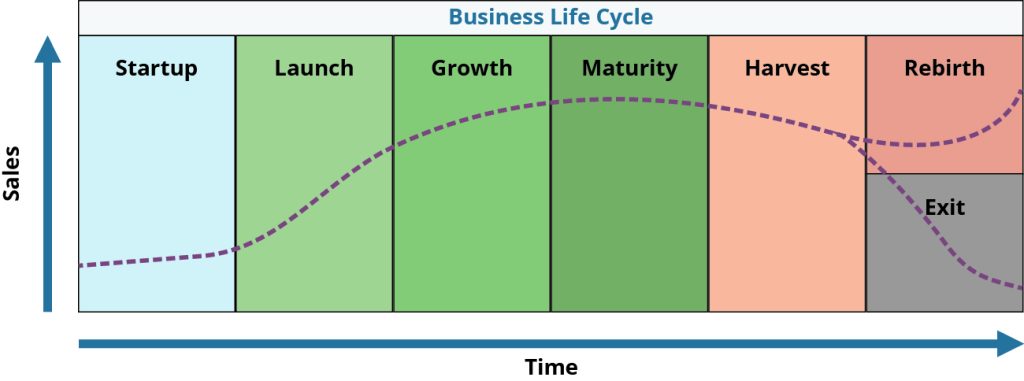

The Entrepreneurial Process: Venture Life Cycle and Product Life Cycle

In general, the entrepreneurial process includes several key stages or some variation of these stages. Keep in mind that these stages do not always follow a sequential pattern, as circumstances and opportunities change. One popular method of understanding and connecting to this entrepreneurial process is to think of your new venture as similar to the human life cycle, the major stages that humans pass through in their life development, and the different growth processes in between.

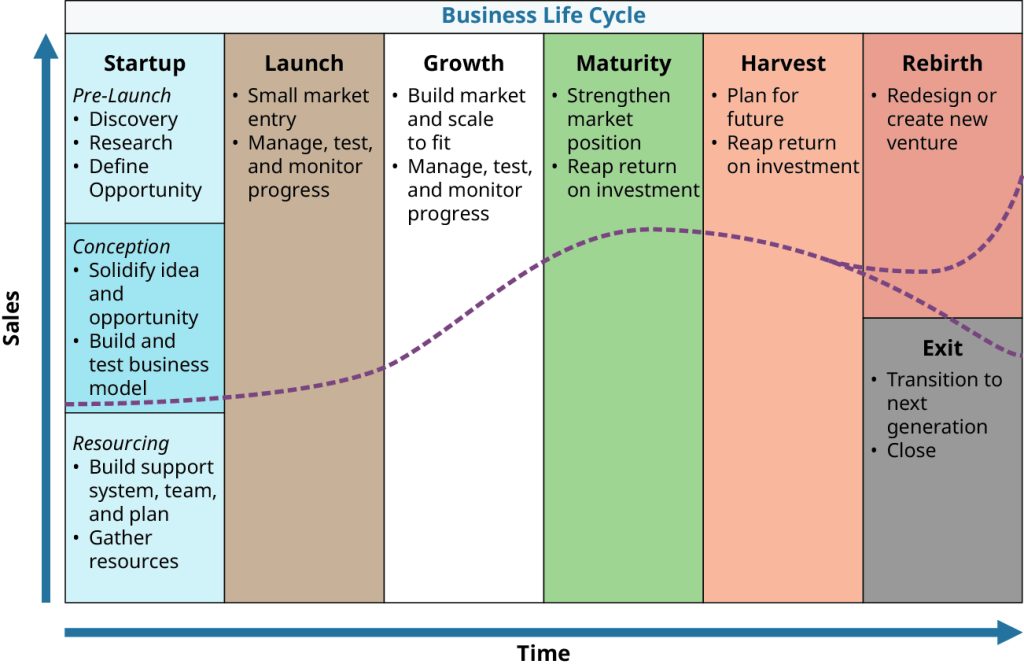

As we can see in Figure 2.18 and Figure 2.19, the startup stage is similar to the birth of an infant. During the startup stage, or the birth of the idea, the venture requires resources to support the startup as the entrepreneur develops the idea, creates the prototype, and builds the infrastructure to support production. During the startup stage, cash supports building the venture. Meanwhile, the startup is seldom ready to generate sales. Planning for this situation, knowing that cash is needed but not replenished through sales, is an important consideration.

Just as a child grows rapidly in their early years, often a business venture experiences quick growth as the product or service becomes commercialized and experiences strong demand, reflected through increasing sales and stronger knowledge and access to the target market. Again, this stage requires resources to support growth. The difference between this stage and the startup stage is cash is generated through sales activity. In some entrepreneurial ventures, however, the growth stage is about building the venture, rather than generating sales. For ventures like YouTube, the growth stage entails increasing the inventory of videos as well as an increase in people accessing the videos.

Just as humans achieve maturity during their life cycle, the business might reach a point where growth slows and perhaps moves into a decline stage. In our human experience, we can take actions to improve or lengthen the maturity stage of our lives through better life choices, such as nutritious eating habits and exercise, to increase longevity and delay decline. We can also extend the maturity of the business and even move into a rebirth and a new growth phase through insightful decisions, such as adding new features to the product or service, or offering the product or service to a new target market. The goal in our lives, and in this analogy, is continued growth and success. Products can be altered or enhanced to extend the product’s life cycle, which also extends the life cycle of the venture.

Examples of avoiding the decline and death of a business fit well into the concept of product life cycle and are prevalent in technology-related products such as the television, the personal computer, and the cell phone. For example, black-and-white televisions underwent a growth stage after World War II. Color televisions were introduced in the 1950s. As technology improved, television manufacturers have repeatedly moved through the life cycle and avoided declines in sales with new features and adaptations with options such as plasma, LED, and smart technology. An example of a product that started and then quickly declined into the death stage of the business is the eight-track player, a music player available between the mid-1960s to the early 1980s. The eight-track player replaced the reel-to-reel tape recorder as a more accessible product for installation in moving vehicles, from cars to Lear jets, to offer individual music purchased by the vehicle owner for listening while traveling. Even as the eight-track player was becoming popular, moving from the introductory stage into the growth stage of the product life cycle, the compact cassette was being developed. In the early 1980s, the compact cassette format replaced the eight-track player, abruptly ending the product life cycle of the eight-track player.

Some products lend themselves more easily than others to managing the life cycle. The goal is to manage the product for continuous growth, whereas other products, such as the eight-track player, are based on technology that quickly becomes obsolete when a better option becomes available. Other examples of products with short life cycles are categorized as fads, like the hula hoop and pet rocks—fads from the past that were reintroduced to a new generation of consumers and that moved quickly through the product life cycle into the last stage—the death of the product with sales either nonexistent or so few that the product becomes a novelty item.

The life cycles of the venture and of the product are two different concepts but are closely related. The venture will need different resources during each stage of the cycle to support the growth and success of the venture. Knowing what stage of the life cycle the product is in assists in decision making. For example, a decrease in sales triggers the need to enhance the product’s value to extend and continue strong levels of growth. From the venture’s perspective, managing the product life cycle also supports the continued success of the venture.

A successful venture avoids decline or death with the potential to prepare for either the sale of the venture or a public offering of stock, known as an initial public offering (IPO), which gives the company access to significant funds for future growth. Two entrepreneurial IPOs in May 2019 were Zoom and Uber. Zoom is a company that offers video conferencing, web conferencing, webinars, and cross-platform access. Uber is a ride-sharing company. Both entrepreneurial ventures used IPOs to support their future plans for growth.

Think about some of the friends you’ve known since childhood compared with those you’ve met in recent years. Suppose you plan to work on a project together and want to figure out who should handle which parts of the work. You might learn some information about a newer friend’s past experiences through conversations, observations, or other collaborations. Even so, it would not be possible—or necessary—to learn everything about their childhood and how they learned a specific set of skills or acquired certain connections. You would just start your interaction and work with your friend from the current time. The same is the case for a venture. You might start a venture from the idea-generation stage or from infancy as part of the pre-launch stage. Or you might join the process after someone else has already completed the early stages of the business—for example, by purchasing an existing business or entering into a partnership. You might not have been around when the business was launched, but you can continue with the development of the business from the present moment. Just as each stage of human experience involves different concerns and milestones, the same holds true for your venture. The venture is your responsibility to manage during each stage of the development process.

Figure 2.20 provides an overview of each stage and the associated decisions that you might consider or encounter for the entrepreneurial process.

Stage 1: Startup

In stage 1, startup activities are related to your perceptions about a potential idea, how you develop your idea, and how you might recognize appropriate opportunities. At this stage, the crucial activity is defining the opportunity to develop your concept into a realizable business venture with a strong potential for success. In this stage, you work on developing the idea more thoroughly to determine whether it fits your current and future circumstances and goals. You will also work through exercises to distinguish ideas from viable opportunities. Each of these actions is addressed in greater detail in future chapters. The goal of this section is to introduce concepts for a greater understanding of these stages.

Key actions or exercises in this stage include:

- Idea development

- Opportunity recognition

- Identification of a market opportunity

- Research and due diligence, or conducting the necessary research and investigation to make informed decisions that minimize risk, such as ensuring you are not duplicating an idea that already exists

Stage 2: Development

Now that you have confidence in your idea, it is time to develop a structure to determine what type of venture will work best for the idea. In Stage 2, you might select a business model (discussed further in Business Model and Plan) and pull together a team (discussed in Building Networks and Foundations) to make your dream venture a reality. The business model identifies how a business will build revenue, deliver value, and receive compensation for that value. Some examples of business models include monthly subscriptions, pre-sale orders, kiosk sales, and other choices. Entrepreneurial decisions in the development stage include many options to consider, including bootstrapping, starting out with limited funds, receiving venture funding from external sources, licensing to receive royalties on a per-item basis, purchasing another business, inheriting a business, franchising either through the purchase of a franchise or building your company with the goal of eventually creating your own franchise, creating a virtual web-based company, using mobile apps that support your business or connect with other businesses, founding a social venture to support a cause, consulting, or freelancing. Choosing among these options or creating your own unique approach to supporting the success of your business will change your results and success level.

Key activities in this stage include:

- Formulation or refinement of your concept

- Design of business model, plan, goals, launch team, and operational structure

- Creation of prototype product to fit market (sample or model for customer feedback)

- Further research and due diligence, as needed

Stage 3: Resourcing

Using knowledge you gained in the first two stages, in the resource stage, you will evaluate the necessary resources to support your new venture. Resources include financial support; support and selection of a manufacturing location or facility (if you are producing a physical product); personnel talents, knowledge, and skills; possible political and community support; and family support, because the new venture will require time commitments that will cut into time with your family. Fundamentals of Resource Planning discusses obtaining resources in more detail.

The key activities in this stage include:

- Gathering pertinent resources, such human and financial capital, investors, facilities, equipment, and transportation

- Establishing connections, networks, and logistics

- Further research and due diligence, as needed

Stage 4: Market Entry

Market entry—the launch of your venture—is often undertaken in a soft launch, or soft open, within a limited market to minimize exposure to unforeseen challenges. As an entrepreneur, you are presenting your new venture to a specific market to see how well it is received and supported. You might make last-minute adjustments at this stage, but the crucial part is to see how the market reacts to your venture. This is an excellent time to scrutinize all aspects of your business for solutions to unexpected problems and improvements in efficiencies, and to track customer reactions to your venture.

One of your most important responsibilities at this point is managing your cash flow, or the money coming into and going out of a business, as cash is essential for the success of the venture. In the early stages of the venture, you will need large amounts of cash to fund the operational activities, because your sales are not yet guaranteed. Production costs, payroll, supplies, inventory, lease payments, and marketing: All of these expenditures involve cash outflows from your venture as part of the startup costs. A successful business needs available cash as well as customers for its products and services, or it will not survive. Key activities at this stage include:

Assessing management structure and needs, adjusting as necessary

- Managing cash flow

- Launching the entity

- Monitoring progress

- Further research and due diligence, as needed

Stage 5: Growth

The growth stage includes making decisions that support the future growth of your venture. In the growth stage, your decisions reflect the scalability of your venture. There is a big difference between a small-scale venture and a venture that must handle significant levels of sales. At this point, your organizational structure needs an update. You might need new functional levels, such as a finance department, or a human resources department, or perhaps an assistant manager. Other considerations include the size of your facilities. Is the current size, or capacity, appropriate for the growth of the venture? Other questions relate to the appropriateness of your suppliers or inventory providers. Are quality and delivery time meeting your needs? Is the payment system appropriate for your venture? In this stage, you should also monitor the growth of your venture and make appropriate adjustments. For instance, if your venture is not growing as expected, then you might go back to your business plan and see what adjustments you can make. Key actions in this stage include:

- Managing the venture

- Making key adjustments, as needed

- Further research and due diligence, as needed

Stage 6: Maturity

In the maturity stage, your venture has moved into the maintenance phase of the business life cycle. Entrepreneurs monitor how a venture is growing and developing according to the business plan, and its projections and expectations. Is your venture growing faster or slower than you expected? What milestones has it reached? What changes are needed to continue the success of the venture? How can you address those changes? Are you still able to maintain or meet the needs of the venture?

Depending on your situation, you still will need to take action to support the venture. Even if the venture is operating efficiently and in a predictable manner, external changes could compel you to change your venture, for example, by making improvements to the product or service, finding new target markets, adopting new technologies, or bundling features or offerings to add value to the product.

One of the key points to understand at this stage is that ventures can, and often do, fail. Entrepreneurship is about taking calculated risks to achieve a reward. Sometimes your venture may not turn out how you planned. Keeping an open mind and learning from experience presents new opportunities for either changes to the existing venture or even a new venture. Consider these examples of early entrepreneurial failures by people who later went on to achieve great success:

- Bill Gates’s early Traf-O-Data company failed because the product did not work

- Walt Disney was told he lacked creativity and was fired from a newspaper job

- Steve Jobs was once fired by his own company, Apple

- Milton Hershey started three candy companies before he founded the successful Hersey Company

Key actions of this stage include:

- Strengthening market position

- Awareness and willingness to change

- Reaping return on investment (ROI)

Stage 7: Harvest

At some point, your company may outgrow your dreams, ambitions, or interests. At this stage, you are harvesting or collecting the most return on your investment while planning how to retire or make a transition away from this venture. Many entrepreneurs enjoy the excitement of starting and building a venture but are less interested in the routine aspects of managing a company. In the field of entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurial team creates a venture with the goal of harvesting that venture. Harvesting is the stage when all your hard work and ingenuity are rewarded through a sizable return on the invested money, time, and talents of the startup team, including any investors. During this stage, the entrepreneurial team looks for the best buyer for the venture to achieve both a return on investment and a match for the continued success of the venture. Key actions in this stage include:

- Identifying what the entrepreneurial team, and investors, want out of the venture, their ROI

- Planning for your future: What’s next on your entrepreneurial journey?

Stage 8: Exit

The exit stage is the point at which your venture either has fulfilled its purpose as a harvested success that is passed along to the next generation of business owners or has not met your needs and goals. These two situations give rise to vastly different scenarios. In the harvesting of the venture, you might receive a sizable cash payment, or a combination of cash payment and a minority share of stock in the venture’s buyout. In an exit that reflects the closing of the venture, your option is most likely liquidation of assets, which you would sell to pay off any remaining creditors and investors. In both harvesting and liquidation, the challenge for you as an entrepreneur can be to accept the emotional withdrawal from a venture that has consumed your thoughts, time, and energy. The time has come for you to step out of the picture and allow the venture to be cared for by a new “parent” or to close the venture completely. Key actions in this stage include:

- Exit strategy and plan

- Transition to the next generation of owners

Stage 9: Rebirth

For some entrepreneurs, the excitement of creating a new venture supersedes the financial gain from harvesting a successful venture. The thrill of transforming an idea into a realizable opportunity and then creating a thriving venture is difficult to find elsewhere. In the rebirth phase, the entrepreneur decides to seek out another new venture to begin the process all over again. As an experienced entrepreneur, you can create a new type of venture or develop a new spin-off of your original venture idea. At this point, you have become a serial entrepreneur, an entrepreneur who becomes involved in starting multiple entrepreneurial ventures. Key actions in this stage include:

- Redesigning or creating a new venture

- Bringing in a new entrepreneurial team or the team from the previous venture.

Exercise

Visit the Man Crates to learn about this entrepreneurial venture.

- Who is their clientele?

- Does this company sell an experience, a product, or both?

- What life cycle stage is this business in now?

- Applying your assessment of the company’s life cycle stage, pretend that you are the CEO of the company. What recommendations do you have for the company’s continued success and growth?

- I. Mount, “Nature vs. Nurture,” Fortune Small Business 19, no. 10 (2009): 25. ↵

- “Summary of North Dakota History – Fur Trade.” State Historical Society of North Dakota, Red River Fur Traders. n.d. https://www.history.nd.gov/ndhistory/furtrade.html ↵

- “Madam C. J. Walker’s ‘Wonderful Hair Grower.’” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/madam-cj-walker%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%9Cwonderful-hair-grower ↵

- “The Color of Blood.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/color-blood ↵

- Russell S. Sobel. “Entrepreneurship.” Library of Economics and Liberty. 2008. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html ↵

- Tim Hindle. “Entrepreneurship.” The Economist. April 27, 2009. Adapted from Tim Hindle, The Economist Guide to Management Ideas and Gurus, Profile Books. ↵

- J. McAllister. “Colonial America, 1607–1776.” Economic History Review. 42, no. 2 (1989): 245–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2596204?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents ↵

- “About Adam Smith.” Adam Smith Institute. n.d. https://www.adamsmith.org/about-adam-smith/ ↵

- Russel S. Sobel. “Entrepreneurship.” The Library of Economics and Liberty. n.d. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html ↵

- B. Zorina Khan and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. “‘Schemes of Practical Utility’: Entrepreneurship and Innovation among ‘Great Inventors’ in the United States, 1790–1865.” Journal of Economic History. 53, no. 2 (289–307) doi: 10.1017/S0022050700012924 ↵

- Susan Stamberg. “How Andrew Carnegie Turned His Fortune into a Library Legacy.” Morning Edition. August 1, 2013. https://www.npr.org/2013/08/01/207272849/how-andrew-carnegie-turned-his-fortune-into-a-library-legacy ↵

- Shontavia Johnson. “With Patents or Without, Black Inventors Reshaped American History.” Smithsonian. February 16, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/with-patents-or-without-black-inventors-reshaped-american-industry-180962201/ ↵

- U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. “First U.S. Patent Issued Today in 1790.” USPTO Press Release #01-33. July 31, 2001. https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/first-us-patent-issued-today-1790 ↵

- “Sybilla Righton Masters.” New Jersey Women’s History. http://www.njwomenshistory.org/discover/biographies/sybilla-righton-masters/ ↵

- Shontavia Johnson. “With Patents or Without, Black Inventors Reshaped American History.” Smithsonian. February 16, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/with-patents-or-without-black-inventors-reshaped-american-industry-180962201/ ↵

- US Patent and Trademark Office. “USPTO Recognizes Inventive Women during Women’s History Month.” USPTO Press Release #02-16. March 1, 2002. https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/uspto-recognizes-inventive-women-during-womens-history-month ↵

- Shontavia Johnson. “With Patents or Without, Black Inventors Reshaped American History.” Smithsonian. February 16, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/with-patents-or-without-black-inventors-reshaped-american-industry-180962201/ ↵

- Alex Camarota. “National Inventors Hall of Fame Inducts Next Class of Innovators.” Inventors Eye. US Patent and Trademark Office. May 2015. https://www.uspto.gov/inventors/independent/eye/201506/index.jsp ↵

- Joel Mokyr. “The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870–1914.” Semantic Scholar. 1998. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/769c/a06c2ea1ab122e0e2a37099be00e3c11dd52.pdf ↵

- Russell S. Sobel. “Entrepreneurship.” The Library of Economics and Liberty. n.d. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html ↵

- Russell S. Sobel. “Entrepreneurship.” The Library of Economics and Liberty. n.d. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html ↵

- Carlos Lozada. “The Economics of World War I.” National Bureau of Economics Digest. January 2005. https://www.nber.org/digest/jan05/w10580.html ↵

- “Joseph Schumpeter.” New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph_Schumpeter ↵

- “Joseph Schumpeter.” New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph_Schumpeter ↵

- “Joseph Schumpeter.” New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph_Schumpeter ↵

- William Whyte. The Organization Man. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956. ↵

- William D. Bygrave, Pamela Lopez-Garcia, and Paul D. Reynolds. “The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Model for Economic Growth: A Study of Venture Capital in 19 Nations.” 2001. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242407165_THE_GLOBAL_ENTREPRENEURSHIP_MONITOR_GEM_MODEL_FOR_ECONOMIC_GROWTH_A_STUDY_OF_VENTURE_CAPITAL_IN_19_NATIONS ↵