1

Consider the pangolin. These oddly adorable, scale-covered mammals poke around among the leaves to find termites, ants and other insects to eat. They look like armadillos, or brown artichokes with feet. There are eight species of Pangolins, living in tropical forests of southern Asia and Africa, and they use their long, sticky tongue to eat ants and termites. When they are bothered by a potential predator, they roll into a ball, relying on their tough scales to protect them. But this doesn’t stop humans from picking them right up and carrying them off, to be diced and sliced and served as food or sold as “medicine”. In some Asian cultures, the scales are thought to have healing properties (although even the Chinese Traditional Medicine institute contends that there is no treatment effect from pangolin scales). The animals themselves are eaten as a delicacy in China and Viet Nam, and have been made into shoes, handbags and belts sold all over the world. All eight species of pangolins are the most trafficked wildlife species in the world; it is estimated that one million individual pangolins were killed between 2010-2020, close to 200,000 were killed in 2019 alone. On top of that, their habitats are being destroyed at an alarming rate.

Another fascinating and imperiled species is the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus). This apparent mish-mash of creatures – a furry, egg-laying aquatic mammal, with flippers, a beaver-tail and duck-bill – is found only in the streams of Australia. Once widespread, the platypus was known from an 1800 mile range in freshwater rivers embedded in tropical, temperate, dry and alpine habitats. It needs natural riverbanks to rest and nest, and it needs clean, free-flowing water. Unfortunately, people have built along the riverbanks, and the rivers are increasingly polluted and dammed. Now climate change is drying up the rivers as well. House cats that have gone wild, an example of an invasive species, prey upon the platypus, further contributing to its decline.

Another fascinating and imperiled species is the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus). This apparent mish-mash of creatures – a furry, egg-laying aquatic mammal, with flippers, a beaver-tail and duck-bill – is found only in the streams of Australia. Once widespread, the platypus was known from an 1800 mile range in freshwater rivers embedded in tropical, temperate, dry and alpine habitats. It needs natural riverbanks to rest and nest, and it needs clean, free-flowing water. Unfortunately, people have built along the riverbanks, and the rivers are increasingly polluted and dammed. Now climate change is drying up the rivers as well. House cats that have gone wild, an example of an invasive species, prey upon the platypus, further contributing to its decline.

But it’s not just the unusual species that are becoming rare. Humans have driven at least 680 species of vertebrates, the best studied taxonomic group, to extinction. Since 1900, 543 terrestrial vertebrate species have gone extinct; this extinction rate is more than 1000 times faster than would naturally have occurred without human overpopulation.

Birds: Forty percent of bird populations, are decreasing around the world. In North America, 389 of 604 bird species are now vulnerable to extinction, with more than half of their current range becoming uninhabitable dur to climate change. In 2021, 23 bird species in the US were declared extinct, including the “Lord God Bird” – the ivory-billed woodpecker, an elusive bird long thought to still be hiding in the swamps of Southeastern US. Birds that nest in the Arctic, where conditions are changing rapidly because of climate change, are particularly vulnerable. As the oceans warm, fish are migrating north, leaving birds that eat those fish, such as the Atlantic puffin, without enough food to feed their young.

Birds: Forty percent of bird populations, are decreasing around the world. In North America, 389 of 604 bird species are now vulnerable to extinction, with more than half of their current range becoming uninhabitable dur to climate change. In 2021, 23 bird species in the US were declared extinct, including the “Lord God Bird” – the ivory-billed woodpecker, an elusive bird long thought to still be hiding in the swamps of Southeastern US. Birds that nest in the Arctic, where conditions are changing rapidly because of climate change, are particularly vulnerable. As the oceans warm, fish are migrating north, leaving birds that eat those fish, such as the Atlantic puffin, without enough food to feed their young.

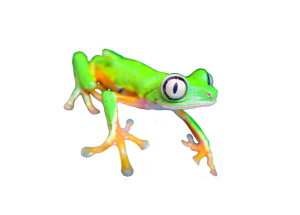

Seventy percent of amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, are declining across the globe. Nearly 168 amphibian species are believed to have gone extinct. Several different causes are interacting to lead to a decrease in reproduction and direct death. Their aquatic habitats have been destroyed at an alarming rate. On top of that, industrial pollutants and pesticides are affecting the gender expression of wild frogs and causing hormonal changes and decreased reproduction and survival. An invasive, foreign fungus is reaching mountain tops and valleys, killing many frogs and salamanders. Amphibians need water to breed, and climate change is drying up their pools and wetlands.

Seventy percent of amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, are declining across the globe. Nearly 168 amphibian species are believed to have gone extinct. Several different causes are interacting to lead to a decrease in reproduction and direct death. Their aquatic habitats have been destroyed at an alarming rate. On top of that, industrial pollutants and pesticides are affecting the gender expression of wild frogs and causing hormonal changes and decreased reproduction and survival. An invasive, foreign fungus is reaching mountain tops and valleys, killing many frogs and salamanders. Amphibians need water to breed, and climate change is drying up their pools and wetlands.

Reptiles: Turtles, snakes, lizards and other reptiles also are imperiled. At least 21% of the world’s reptiles are close to extinction. These wonderful animals are plucked out of the wild and taken home as pets, they are trapped and made into soup, snacks, belts, boots, buttons, cures and combs; they are run over as they bask in the sun or try to cross the road; their habitats are cut and paved and turned into cropfields; and as the climate changes, the genders of their temperature-sensitive eggs are altered in some species.

Even insects are in trouble. Because of pesticides, habitat loss, climate change and other factors, 40% of insect species are declining, and about one-third of insect species are going extinct; one study found an 80% decrease in beetles since the 1970s. Insects are critical to our native ecosystems, providing pollination for plants that produce fruits and other foods for humans and the many other species. Insects are also an important part of the foot web, including decomposing waste and recycling nutrients which improve soil health. Other invertebrates, including species of crabs, shrimp, spiders, jellyfish and octopus, are also endangered.

Even insects are in trouble. Because of pesticides, habitat loss, climate change and other factors, 40% of insect species are declining, and about one-third of insect species are going extinct; one study found an 80% decrease in beetles since the 1970s. Insects are critical to our native ecosystems, providing pollination for plants that produce fruits and other foods for humans and the many other species. Insects are also an important part of the foot web, including decomposing waste and recycling nutrients which improve soil health. Other invertebrates, including species of crabs, shrimp, spiders, jellyfish and octopus, are also endangered.

Supporting the ecosystems that these rare animals occupy are plants, fungi, and microbes, many of which are declining as well. Most people don’t think about plants when they think about endangered species, but 40% of the world’s plant species are declining. About one in five of plant species are threatened with extinction, most of them in the tropics. A lot of plants are killed when people need the plant’s habitat for farms, mining, buildings and roads. Plants also become endangered when they are outcompeted by introduced, aggressive plant species, or are eaten by non-native herbivores. Some plant populations decline because collectors dig them up out of the wild to eat them, make them into medicines or sell them to horticulturists.

Supporting the ecosystems that these rare animals occupy are plants, fungi, and microbes, many of which are declining as well. Most people don’t think about plants when they think about endangered species, but 40% of the world’s plant species are declining. About one in five of plant species are threatened with extinction, most of them in the tropics. A lot of plants are killed when people need the plant’s habitat for farms, mining, buildings and roads. Plants also become endangered when they are outcompeted by introduced, aggressive plant species, or are eaten by non-native herbivores. Some plant populations decline because collectors dig them up out of the wild to eat them, make them into medicines or sell them to horticulturists.

All in all, more than 40,000 species are threatened with extinction, 28% of all assessed species. A compilation of research by the World Wildlife Fund, one of the top organizations devoted to species conservation, found that, from 1970-2016, populations of wild species have declined an average of 68%. This was based on data from 20,811 populations of 4,392 species. And that’s just the species we know about – new species are being discovered every day, and unknown species are being lost every day as well.

Animals, plants, fungi and all manner of living creatures all around the world are disappearing, as people kill them directly for food and other uses, and as our activities destroy and degrade their habitat. succumbing to the “four horsemen of the Apocalypse”: Habitat destruction, invasive species (including new predators, competitors and diseases), pollution, and overharvesting. This is not news. But now, on top of those forces of destruction, we have added climate change.

Climate change means warmer global temperatures, more frequent and more severe droughts, more rain and floods in some places, more wildfires, higher sea levels, more acidic oceans. Species that can move easily will move to the right kind of habitat, if it exists and they can get there. Cooler mountaintops, deeper cooler waters. Some species may be able to adapt, through the process of natural selection. But many species will not be able to do either. Even without all of the other problems they were already facing, climate change alone would push over 60% of tropical terrestrial species towards extinction, much higher than other species. Most species have a 12% risk of going extinct due to climate change; species that live on islands and mountain tops have an estimated 84-100% risk of extinction due to climate change, because they have nowhere to go. Marine species are more mobile, and thus their extinction risk is lower, thus “only” 54% of marine species are expected to go extinct due just to climate change.

And, although the focus of this book is on non-human life forms, climate change is already having horrendous effects on people, too. In Pakistan, Kuwait, Iran, India and other areas, the temperatures have hit over 127° F in 2021. In July of 2022, Europe, North America, the middle East and Asia all experienced heat waves with temperatures over 104° F (40° C), causing many deaths. In Senegal, a normally dry area, a massive rain storm brought more rain than they usually get in three months – all in one day, leading to flooded streets and washed out fields. In the US, water levels in the Colorado River are lower than they have ever been. Arizona, California and New Mexico are fighting over the dwindling water needed for drinking, washing, irrigating crops and other important uses. Two destructive hurricanes hit Honduras within the same week, causing 94 deaths. Low-lying islands and coasts are being drowned by rising sea levels.

But there is some hope. All 200 countries in the world recently signed the Paris Climate Agreement. And 187 nations of the world are now signatories to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, introduced in 1992 at the Rio ‘Earth Summit’. Through this agreement, the world has made important, science-based decisions and gained financial support to put together serious, sustainable projects on the ground. The convention on Biological Diversity, “offers hope for the future by forging a new deal between governments, economic interests, environmentalists, indigenous peoples and local communities, and the concerned citizen.”

As an example, going back to our pangolin friends, all eight pangolin species are protected under national and international laws, including a Chinese law enacted in 2020 that made it illegal to kill or eat any pangolin, or use pangolin scale sin medicine. However, the laws need to be enforced in order to be effective, and the needs of the people must be addressed; if people don’t find a way to survive without killing pangolins, these laws won’t work.

This book takes a “big picture” approach to understanding and saving biodiversity, by focusing on ecosystems. First, we explain the important principles of ecology and sustainability. Then, each chapter explains how the major ecosystems of the world work, why they are important, and what threats they face. Each chapter ends with a “sustainability story”, chosen from the many, many examples of how people are responding to the challenges of saving biodiversity. If we are to keep these marvelous creatures alive on this planet, we need to make sure that the solutions we implement consider the needs of the ecosystem and its inhabitants, including people.

We hope every reader of this book will be inspired to take action to save the biodiversity of our beautiful planet.

References

Ennen, J. E. et al. 2018. Where Have All the Turtles Gone, and Why Does It Matter? BioScience, 00063568, Oct2018, Vol. 68, Issue 10

Hayes, T. B., Falso, P., Gallipeau, S., & Stice, M. (2010). The cause of global amphibian declines: a developmental endocrinologist’s perspective. The Journal of experimental biology, 213(6), 921–933. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.040865

Kew Gardens. 2020. 2020 State of the World’s Plants and Fungi Report. https://www.kew.org/science/state-of-the-worlds-plants-and-fungi

New York Times. 2020. Postcards from a World on Fire. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/12/13/opinion/climate-change-effects-countries.html

Readfearn, Graham. 2021. Glum future for the platypus. The Guardian, Jan. 8, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jan/09/glum-future-for-the-platypus-why-the-elusive-mammal-is-disappearing-under-our-noses?fbclid=IwAR3YJeSeZHxROc1MDbhg2x_2UsADHu9RaR3KmPPp6xZ57hdMPEw5ZWvWbb4

Sánchez-Bayo, Francisco, and Kris A.G. Wyckhuys. 2019. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biological Conservation. 232: 8-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Platypus. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/40488/21964009

United Nations. 2022. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/convention/guide/?id=next

World Wildlife Fund (WWF). 2021. The Fight to Stop Pangolin Extinction. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-fight-to-stop-pangolin-extinction

Photo credits:

Pangolin: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Platypus. Cabrera, Angel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Box turtle: I, Jonathan Zander, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Lemur leaf frog. Frogmana, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Dragonfly. Sven Damerow, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Puffin: Richard Bartz, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Monkeyflower: Steve Schoenig, CC BY-SA, personal communication with the author.