1 Curriculum Integration of Simulations

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this learning module, the learner will:

- Discuss the elements of systematic/purposeful integration of simulations in curriculum

- Analyze enhancers/barriers to successful integration of simulations in curriculum

- Create a plan for systematic integration of simulations in nursing curriculum

Introduction:

Simulation is an integral component of nursing education because it allows for a safe, timely, and prescriptive approach to meet learning objectives at the levels of simulations, courses and academic programs (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021). There is currently an extensive amount of literature supporting the ability of simulations to provide rich learning experiences, especially clinical situations that they might not have had access to as students/learners. However, isolated simulation encounters that are not carefully integrated into an organized curriculum can result in ineffective and inefficient use of time for both educators and learners (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021; Herrington & Schneiderith, 2017; Howard et al, 2019; Thomas et al, 2016). It is, therefore, imperative that nurse educators and simulationists exert efforts to ensure the systematic integration of simulations in curricula in academic, and even in practice settings. Simulation-based education is a costly educational modality, and the maximum benefits can be achieved, when simulations are well integrated in the curriculum to meet not just individual simulation objectives, but course and program objectives as well (Masters, 2014). Like any novel undertaking in educational programs, a curricular integration framework must be used, and a curricular plan made available for implementation and evaluation. This learning module unfolds to discuss the concept of curricular integration, theoretical and empirical bases for simulation-based education in nursing curriculum, and essential steps and elements of curricular integration. Exercises to check knowledge and apply learned concepts are included along with video resources to further highlight concepts of curricular simulation integration.

Knowledge Check:

I. Integration of Simulations in Nursing Curricula

Curriculum simulation integration, among other definitions, is the coordinated and purposeful use of simulation-based learning methods to meet predetermined learning goals within an approved curriculum (Franklin & Blodgett, 2021). Simulations are incorporated in each course or level to promote psychomotor, cognitive and affective domains of learning (Schram & Aschenbenner, 2014). Simulations are used in different settings in nursing education; from simulated clinical situations to replace part (or all) of clinical experiences that traditionally happen in real patient care situations, to simulations used to illustrate clinical experiences in the classroom. The National League of Nursing (NLN) Vision Series (National League for Nursing, 2015) articulates the vision of using simulations across the curriculum: simulation pedagogy transcending the simulation laboratory and viewed as an innovative way, a break from the long held nursing education traditions.

II: Theoretical and Empirical Support for Simulation-Based Education in Nursing

Empirical Bases

Aul et al. (2021) found systematic curricular integration of simulations in a nursing program curriculum enhanced teaching and learning needs of faculty. The authors research is not an isolated study. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) National Simulation Study generated support of simulations replacing 25%-50% of traditional clinical experiences (Hayden et al, 2014). Unlike traditional clinical education, empirical support of the use of simulations in clinical education has advanced and has been used to support standards of best healthcare simulations (INACSL, 201) and guidelines for using simulations in nursing education (NCSBN, 2016). The NLN (2015) advocates for debriefing across the curriculum; and NCSBN (2016) Simulation Guidelines for prelicensure nursing programs cite several systematic reviews and the National Simulation Study to support the use of simulations in nursing curriculum:

- Lapkin et al. (2010) conducted a systematic review of eight studies that met their inclusion criteria. They found that simulation improved critical thinking, performance of skills, knowledge of the subject matter and an increase in clinical reasoning in certain areas. Two integrative reviews of undergraduate nursing’s use of simulation focused on patient safety.

- Berndt (2014) reviewed seventeen studies, including 3 systematic reviews. Their findings support the use of simulation as an educational intervention to teach patient safety in nursing, particularly when other clinical experiences aren’t available.

- Fisher & King (2013) conducted an integrative review related to patient safety in that they examined 18 studies preparing students, through simulation, to respond to deteriorating patients. They found that, in general, confidence, clinical judgment, knowledge and competence increased through the use of simulation.

- The largest and most comprehensive study to date examining student outcomes when simulation was substituted for up to and including 50% simulation was NCSBN’s National Simulation Study (Hayden et al., 2014). This longitudinal, randomized, controlled study replaced clinical hours with simulation in prelicensure nursing education. In ten nursing programs from across the country (five BSN and five ADN), students were followed through all clinical courses in their nursing programs as well as through their first six months of practice. The study provided evidence that when substituting clinical experiences with up to 50% simulation, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups using 10% or less of simulation (control), 25% simulation or 50% simulation with regard to knowledge acquisition and clinical performance. In conclusion, the literature provides evidence that simulation is a pedagogy that may be integrated across the prelicensure curriculum, provided that faculty are adequately trained, committed and in sufficient numbers; when there is a dedicated simulation lab which has appropriate resources; when the vignettes are realistically and appropriately designed; and when debriefing is based on a theoretical model.

Simulation research has advanced to what it is today, establishing its relevance and necessity in nursing education. It is important for nurse educators, as they attempt to integrate simulations in the nursing curriculum to be cognizant of current empirical evidences and guidelines for using simulations in nursing education.

Theoretical Bases

The theoretical bases of simulation are sound learning theories, and are frequently used in simulation education and research:

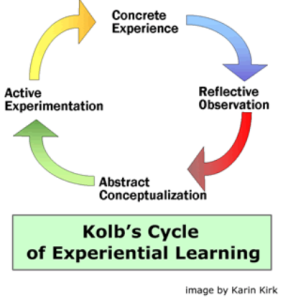

- Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory:

Kolb describes a cognitive learning process where individuals have concrete experiences, followed by reflection, generation of abstract conceptualizations and application of new knowledge to future practice (Franklin & Blodgett, 2020, citing Kolb, 1984) (See image above). Kolb’s theory resonates with modern nursing simulation: active participation in a simulation experience (concrete experience), followed by reflective observation and abstract conceptualization occur in debriefing of simulations. The cycle is completed through learners active experimentation of learned practice in another simulation or in actual patient care.

Reflection Question

How can nurse educators use Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory in planning for real and simulated students’ clinical learning experiences?

2. Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive Load Theory in a nutshell:

The application of Cognitive Load Theory is discussed in the following video. Cognitive load theory underpins simulation scenario design.

Key Takeaways

As nurse educators, how do we take into account intrinsic load, germane load and extraneous load of our learners in the design and facilitation of simulations? What are the implications in curricular integration?

- What are your prebriefing plans?

- How simple or complex are the simulations in each course? Are they appropriate for the learner’s level in the program?

- Reflect on other ways to use this frame (Cognitive Load Theory) in your curriculum.

3. NLN Jeffries Simulation Theory

The following are notable points of the theory based on NLN Jeffries Simulation Theory: Brief Narrative Description (Jeffries et al., 2015).

- Context refers to contextual factors that need to be taken into consideration when designing and evaluating simulations such as setting and overarching purpose of simulation.

- Background refers to the theoretical perspective for the specific simulation experience and how the simulation fits into the larger curriculum.

- Design includes specific learning objectives that guide the development or selection of activities and scenarios with appropriate content and problem-solving complexity (physical and conceptual fidelity, roles, scenario progression, and prebriefing and debriefing strategies)

- Simulation Experience is characterized by an environment that is experiential, collaborative and learner-centered (psychological safety, suspension of disbelief)

- Facilitator and Educational Strategies in the context of the simulation experience is a dynamic interaction between facilitator and participant. Some of the important facilitator attributes include skill, educational techniques and preparation. For example: “The facilitator responds to emerging participant needs during the simulation experience by adjusting educational strategies such as altering the planned progression and timing of activities and providing appropriate feedback in the form of cues (during) and debriefing (toward the end) of the simulation experience.”

- Participant innate attributes include age, gender, level of anxiety and self-confidence, whereas preparedness for simulation is modifiable.

- Outcomes: a) Participant outcomes include reaction, learning, behavior; b) Patient and c) System

Key Takeaways

In planning for Curriculum Integration:

- Our plans to integrate simulations in existing simulation must be based in sound educational theories

- The planning, design, implementation and evaluation of simulations must be planned in curricular integration using the NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory.

III. Curriculum Integration Framework

This video provides an outline of curriculum integration and important concepts will be highlighted in the text below (GWU School of Nursing open educational resource):

A. Needs Assessment

(Kern’s Steps 1 and 2)

Understanding the following required elements is necessary to determine the need to integrate simulations in the curriculum:

- Underlying cause of concern

- Organizational analysis

- Stakeholders’ survey

- Program outcome data

- Self-study comparing current practices to INACSL standards of healthcare simulations

- Accreditation reports

- Standardized test results

- Didactic Examinations

- Feedback from clinical partners

- QSEN competencies

- Learners Needs and learning style preferences

Highlighting the need for Inter-professional Education (IPE) and Simulation Enhanced IPE (SIM-IPE)

Key Takeaways

A statement indicating the desired state, compared to current state, supported by objective data and standards of best practice, is needed to propose a curricular integration of simulations in the curriculum.

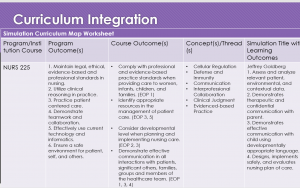

B. Goals and Objectives- Curricular mapping

(Kern’s step 3)

The learning goals and objectives of simulations must be linked to content, courses, and the overarching program outcomes. A curricular map will allow faculty to scaffold simulation experiences and build and content and complexity from previous courses. Scaffolding allows learners to demonstrate knowledge, skills and attitudes, add new knowledge, and apply new material. Scaffolding promotes learning efficiency (Franklin & Blodgett, 2020). Curricular mapping requires input from faculty across the curriculum along with simulation faculty. Simulations objectives must be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time bound (SMART), and must be linked to unit objectives, course objectives and end of program student learning outcomes.

- Determine how content can be thoughtfully linked to context

- Lay out a curricular map to explore areas needing improvement

- Match simulation to didactic content for each course

Curricular alignment is a linear configuration between program outcomes, course outcomes, and simulation outcomes. If program outcomes drive course outcomes, then course outcomes should drive simulation outcomes. If we design simulations that adhere to the Standards, then all simulations should clearly map back to program outcomes. Simulations are no longer run to compensate for clinical time or replace hours lost to other activities, but instead are designed to address specific course outcomes (Schneidereith & Beroz, 2017).

Examples

This is an example of a Curriculum Map Worksheet: MCSRC Simulation Curriculum Map Worksheet

C. Educational Strategies

(Kern’s Step 4)

- Simulation is an educational strategy that is framed by educational theories, including constructivism, experiential learning, and andragogy. Current standards of healthcare simulations provide guidance to educators on design, implementation, and evaluation of this teaching-learning modality. See HEALTHCARE SIMULATION STANDARDS OF BEST PRACTICE™

- Planning and Sequencing Simulation Experiences: Thoughtful curricular integration reduces the variability brought about by different clinical experiences; nurse educators will need to plan to include simulations that allow students to safely practice frequently required competencies along with the ability to practice clinical situations that students are not otherwise able to practice independently because of safety and legal considerations. Nurse Educators will need to plan and make decisions on writing simulation scenarios or utilize peer reviewed scenarios. Both will require alignment with course and program learning objectives.

- Simulations are a powerful teaching and learning modality beyond the simulation laboratory. An example is illustrated in the resources below:

D. Implementation

( Kern’s Step 5)

- The simulation experience should have maximum realism so that students do not spend cognitive energy understanding what is real and what must be imagined (Franklin & Blodgett, 2020; Screws & Cason, 2019). This has huge implications on budgeting operations; faculty must present a strong business case on the maximum return or gains in the integration of simulations in the curriculum.

- Utilizing Simulation Education Resources: Although simulations can curricular needs and gaps, available and potential resources must be taken into consideration such as: faculty and administrative support, size of student population/cohorts, clinical hours, clinical to simulation hours ratio, faculty competencies, simulation space and set up, and debriefing space.

- It is crucial to match the level of fidelity and the level of learners’ level of experience; it is important that the level of fidelity matches both scenario objectives and learners’ needs. Simulation modalities and their availability are important factors to consider in the implementation of simulations. Various modalities include low to high fidelity manikins, standardized patients (actors), tasks trainers, virtual simulation modalities, visual aids and computer systems and competent staff. These are elements that will enhance implementation of simulation-based curriculum.

Highlight on Standards of Best Practice in Simulations and Standardized Patients/Human Players

The Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE) Standards of Best Practice (SOBP)

Podcast: Learning From Our Failures: SPs from Center for Medical Simulation

Reflection: What special considerations do we consider as nurse educators in using Standardized Patients in the Curriculum?

VIRTUAL SIMULATION

Tolarba (2021) states virtual simulation (VS) is more effective than simulation in a nursing lab; VS improves affective and cognitive domains of learning, increases students’ clinical skills, technology skills, confidence, and enjoyment.

What is VS and how can it be integrated into curriculum? How can you evaluate it’s effectiveness? Click here to find out: Virtual Simulations SEL II_2023.pptx

This is a comprehensive educator’s toolkit on the use of virtual simulations in healthcare

F. Evaluation of Simulations

(Kern’s Step 6)

- Well-defined learning outcomes are critical to the success of a simulation activity. Yet outcomes, in turn, should get educators to consider how they’re going to evaluate their simulations, similar to how educators should “begin with the end in mind” when

programming simulation activities. Tagliareni and Forneris (2016) believe there should also be a focus on evaluation of the simulation activities overall. To that end, they recommend faculty and curriculum developers build in evaluations that evaluate:- 1. total number of anticipated simulations

- 2. student learning

- 3. students’ simulation experience (whether or not the experience is being implemented consistently across classes and courses, for example)

- 4. the simulation program as a whole (how effective it is at positively impacting outcomes, for example)

- 5. faculty development including roles and responsibilities and best practices in using simulation

- 6. evaluation of faculty facilitation (how does it compare to the facilitation conducted in the classroom?) (Tagliareni & Forneris, 2017).

- Evaluation results data for each individual simulation encounter should be analyzed and incorporated back into the course. Analysis should address whether the activity met the learning outcome for the course, using quantitative data (which many of the instruments referenced above are designed to measure) so that faculty can quantify learning and thus, more easily map the data to student, course, and curriculum outcomes (Tagliareni & Forneris, 2016).

- The NLN/Jeffries Simulation Theory frames the needs and elements of evaluation of simulations (Jeffries, et al., 2016). A repository of instruments is found in INACSL Repository of Instruments used in Simulation Research and the standards are written in Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM Evaluation of Learning and Performance

Exercises

Question: What lessons can we take from the article that will lead our programs to successful integration of simulations?

VI Additional Resources:

2. MCSRC Summer 2020 Speaker Series: Curricular Integration by Tonya Scheneiderith

3. Video Series: Debriefing in the Classroom and beyond:

- Debriefing in the classroom

2. Debriefing Post-Clinical Day:

3. Debriefing a critical incident in clinicals:

References:

Aul, K., Bagnall, L., Bumbach, M. D., Gannon, J., Shipman, S., McDaniel, A., & Keenan, G. (2021). A key to transforming a nursing curriculum: Integrating a continuous improvement simulation expansion strategy. SAGE Open Nursing, 7, 2377960821998524. https://doi.org/10.1177/2377960821998524

Franklin, A. E., & Blodgett, N. P. (2020). Simulation in undergraduate education. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 39(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.39.3

Jeffries, P. R., Rodgers, B., & Adamson, K. (2015). NLN Jeffries simulation theory: Brief narrative description. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(5), 292–293. https://doi.org/10.5480/1536-5026-36.5.292

Masters K. (2014). Journey toward integration of simulation in a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. The Journal of Nursing Education, 53(2), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20131209-03.

National League for Nursing (2015). NLN vision series: A vision for teaching with simulation. https://www.nln.org/docs/default-source/uploadedfiles/about/nln-vision-series-position-statements/vision-statement-a-vision-for-teaching-with-simulation.pdf?sfvrsn=e847da0d_0

Tagliareni, E & Forneris, Susan (2016). Curriculum and simulation: Are they related? Wolters Kluwer/National League for Nursing. White Paper.