1 Welcome to The Anthropology of Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion

Chapter 1 audio can be accessed on Soundcloud. Instructor resources are available on Canvas Commons.

Chapter 1 Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Explain and distinguish the complex definitions of “magic,” “witchcraft,” and “religion.”

- Summarize and discuss the goals and research methods of cultural anthropologists.

- Critique the work and motivations of colonial anthropologists.

- Apply the principle of cultural relativism.

- Apply an intersectional and holistic approach toward the analysis of cultural beliefs and practices.

1.1 Welcome to The Anthropology of Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion

“The Anthropology of Magic, Witchcraft, and Religion” is a classic course in departments of anthropology all over the world. In part, this is because every culture engages with these three topics. Their universal presence across cultures provides lessons about our shared nature as humans. At the same time, every culture engages with these topics in its own way. Their diverse expression across cultures also warrants explanation.

What exactly do we mean by the terms “magic,” “witchcraft,” and “religion?” And why should we care – either about the terms themselves, or about the anthropological study of magic, witchcraft, and religion more broadly? In this chapter, we provide detailed answers to the first set of questions: questions about terms, definitions, and their implications for how we might organize our thoughts and think more critically about humanity and about the world.

Throughout this text, we also present a response to the second question (“Why should we care?”). That response involves explicit statements about the value of anthropological perspectives on magic, witchcraft, and religion (don’t worry if you’re not sure what anthropology is yet – this will be defined soon enough!). We will also explore case studies that illustrate anthropology’s direct impacts on the world around us, in the past, present, and hopefully in the future as well.

We encourage you to reflect on the impacts that the anthropological study of magic, witchcraft, and religion have in the present day while you are reading this text or taking the course it’s assigned for. If you have questions or comments as you reflect, share them with your instructors and classmates, or you can even reach out to us (the authors of this textbook).

1.2 What is Anthropology?

Before we can begin our exploration into the anthropological study of witchcraft, magic, and religion, one key term first requires discussion. That term is anthropology. Anthropology is the study of humanity. Anthropologists – the scientists, scholars, activists, and other cross-cultural and data-driven critical thinkers who do anthropology – are interested in all elements of human life. There are four major fields of anthropology:

- Anthropological archaeology: the study of human behavior using objects people have left behind.

- Linguistics: the study of the human experience through language.

- Biological anthropology: the study of human biological diversity and evolution.

- Cultural anthropology: the study of human cultural variation, as well as its causes and its impacts.

Although we will encounter elements of all four fields of anthropology, the contents of this course most often fall under the category of cultural anthropology (but see below for more on this). Cultural anthropologists are interested in every part of human culture, including religious beliefs and practices, but also political structure, family organization (kinship systems), economies, and much more. This is in part because, as you can imagine, the term culture is hard to define. We may use it to refer to a group’s beliefs or practices or sense of identity, to symbols and objects, or to shared knowledge. In this text, we will often approach culture simply as “the way human beings create meaning in their lives.” Again, this is only one of many possible definitions, but it is one that we will ask you to keep in mind and to reflect on throughout the text. The anthropological study of meaning-making, otherwise known as semiotics, is a central focus in our class. Taking a semiotic approach toward culture means that while we examine our own cultures and the cultures of others, we will not just strive to understand what different cultural groups believe or how they express those beliefs. We will also consider how humans actually produce (and reproduce) beliefs, meaning, and culture itself.

Exercise 1A

Anthropology is the study of humanity and modern anthropologists use unique research strategies to

better understand the complex human experience. Listen to this 4-minute radio story that explores the work of anthropologist Jason De León to better understand how anthropological research can be used to address modern problems.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- How does De León use physical objects to better understand human experience and human culture? What does his research reveal about the material needs of humans?

- How is meaning created in human life? Consider concepts like nationality, migration status, and employment opportunity in your response.

1.3 What is the Supernatural?

As discussed above, anthropologists study humanity and seek to gain a better understanding of the human condition and the human experience. To do so, we need terms that allow us to study human cultures in an unbiased and comparative way. Nowhere is this more true than in discussions of scientifically-unverifiable beliefs like many of the topics covered in a course on magic, witchcraft, and religion. To describe these kinds of beliefs, we use the term supernatural, which refers to anything that people might believe exists, but that falls outside the laws of science or the natural world. Even though supernatural beliefs cannot be proven or disproven by the scientific method, they still maintain a central role in the cultural identities of human groups throughout the past and present.

Three major concepts we explore throughout this text that each engage with the supernatural are “magic, witchcraft, and religion.” Anthropologists define these concepts in a manner that may not be in line with the way you have heard them used colloquially, or even with the ways you tend to use them yourself. For the purpose of clarity in the rest of this text, we will define each term below.

1.4 What is Religion?

We use the term religion to refer to a system of beliefs, symbols, and practices that have at least some supernatural elements. These systems often impact the way members of a culture understand reality and shape people’s lived experiences, behaviors, and attitudes. Of course, there are also many non-religious areas of culture – those that do not engage with the human soul, the afterlife, the divine, and with other supernatural elements – that influence people’s lived experiences as well (e.g., politics, science, beliefs and expectations about gender norms).

Critically, the “supernatural elements” that make up a religion vary enormously in their specific details. Some religions believe in one god, some believe in multiple gods, some believe in spirits, and others don’t believe in or explicitly identify any gods or spirits at all. What is important is that religions are faith-based; because they involve the supernatural, they cannot be proven through science. If a religious belief could be proven by using the scientific method, it would by definition cease to involve the supernatural. And yet, although its beliefs cannot be scientifically proven “true,” we certainly know that religion is “real” because of the impact that it has on people’s lives.

All this being said, the term religion is nonetheless exceptionally hard to define in a satisfactory way because so much variation exists in the range of ideas, behaviors, and associations that the term conjures up. We want to be able to discuss religion in a universal way: one that includes all belief systems and practices that we intuitively associate with the term. This way, or cross-cultural exploration might actually hope to glimpse the full range of variation in human beliefs and practices relating to the supernatural. At the same time, students may be tempted to object to a definition of religion so broad that it starts to include belief systems that don’t intuitively seem like religions to them. Compromises will have to be made in our course, and along the way, we might just realize that many seemingly “non-religious” beliefs and practices we take for granted as part of human cultural life in the past and present do in fact fall into the category of “religious beliefs and practices.” Another way to say this is that if we define the phenomenon clearly, we may be able to identify supernatural thinking in places we didn’t already realize that it operates.

1.5 What is Magic?

We use the term magic to refer to a person’s efforts to change their life through supernatural means. Magical rituals differ from religious ones because the latter involve whole communities. In contrast, magic addresses individual needs. If “a farmer wants rain, a young man wants a wife, a woman needs a cure for her illness [they might use magic to fulfill their desires… Magic] is directed at very practical ends as articulated by an individual” (Frankle 2005, 137). Put differently, magic has a definite beginning and end; it involves someone who desires something and the specific outcome they desire (Graeber 2001, 245-246).

Consider an example. If you are unable to pay your rent this month and you decide to sell your bike to make ends meet, you aren’t engaging in magic because the steps you are taking are not supernatural. However, if you are unable to pay rent this month and decide to take action by following the principles of Feng Shui, you might place a money plant in your living room facing south. This would be considered a magical action because your efforts are engaging with supernatural forces that cannot be directly observed or explained by scientific means.

Other examples of magic use would include instances when people pray to supernatural beings to grant them specific outcomes. Sunday prayers to the Christian deity Jesus Christ may fall under the heading of “magic” if the person or people praying are praying for something specific. Since engagement with this deity is not scientifically or naturally observable, they are “supernatural,” for the purposes of our analysis as anthropologists. In general, by praying to any divine beings with specific goals in mind, you are conducting magic: engaging with supernatural forces in an attempt to change your circumstances.

1.6 What is Witchcraft?

- First, we use the term to refer to the many different religious communities who refer to themselves as witches. Although this form of witchcraft actually exists in many forms, it is often the case that witches believe in the supernatural powers of the “natural” world (parts of the world that are not human-made).

- At the same time, many societies also use the term “witch” as an accusation intended to punish people who don’t conform to society’s standards.

We will explore the very different lessons, histories, and belief systems associated with these two uses of “witchcraft” (witchcraft as a description of one’s own spirituality and witchcraft as an accusation against others) at length in this course.

1.7 A Word about Our Goals as Cultural Anthropologists

Anthropologists are not interested in determining which religions or belief systems are “better” or “worse,” or are we interested in deciding which religions or belief systems are “true” or “false.” In fact, decisions about what is “true,” “false,” “better,” or “worse” are not universal (they are culturally specific) and are therefore impossible to make with any kind of scientific or unbiased certainty. In this text, you will be challenged to engage with concepts that may be different from your personal understanding of reality, and we urge you to stretch your mind to understand the beliefs of people who think differently about the world than you do. To enter the study of magic, witchcraft, and religion without an open mind will hinder your ability to understand the course material.

Remember that your goal this semester is to understand the beliefs and practices of others – and of your culture too – while also developing your own unique perspective. You are not expected to like or to agree with everything that we discuss in this course, but you are expected to work hard to understand how anthropologists and other scholars study the topics of magic, witchcraft, and religion, and why other people’s religions and spiritual beliefs are as valid as your own.

1.8 Anthropology and Holism

While this course specifically focuses on magic, witchcraft, and religion using perspectives drawn from cultural anthropology, we also incorporate ideas from linguistic anthropology, anthropological archaeology, and biological anthropology. Anthropologists call this a four-field approach toward the study of humanity, and we use it because we acknowledge that there are connections between the cultural, biological, linguistic, and material aspects of human life. In fact, these connections are quite common; no part of a culture exists in total isolation.

For example, think of all the ways that religion can be affected by “other parts of culture”:

- Economic forces might favor the development or disappearance of specific types of religious practices over time, affecting the way that a religion changes.

- There are laws in most countries that govern how religious institutions can operate. These laws can affect whether and where a religion spreads and might even lead to conflicts between religious institutions and governments.

- Cultural norms and beliefs about what constitutes acceptable behavior likely also affect elements of a religion. For example, consider ideas about what forms of dress are appropriate; what defines masculinity, femininity, or even “success”; what a “normal” family should look like. All of these cultural expectations might shape how the beliefs, behaviors, and symbols that are part of a given religion develop or how people might receive (or reject or transform) them.

In this sense, religion is always connected to other parts of culture, both impacted by and impacting culture in various ways. Clearly, religion cannot be understood effectively if we fail to take its cultural surroundings into account.

In fact, any part of a culture is similar in that it is connected to other cultural institutions. For this reason, anthropologists use what we call a holistic perspective to study culture. Rather than using a naive approach that expects to simply and easily delineate a single part of culture in which we are interested, we instead seek out the connections between cultural institutions like religious beliefs, kinship systems (family structure), economies, gender ideology, political life, cultural understandings of health, and much more.

Anthropologists know that we have to consider the whole cultural situation – using a perspective we call holism – if we want to understand the reality of a person’s cultural experience. Holism refers to the idea that no “part” of a culture exists by itself. Later on in this course, you will be asked to examine the cultural practice of cannibalism holistically in order to understand how spirituality, gender roles, and language all play a role in one anthropologists’ examination of the practice (see Chapter 11).

For now, consider these examples of how anthropologists use holism. The perspective will come up frequently throughout our course:

- Medical anthropologists worked in West Africa throughout the Ebola epidemic. Simply examining the genetic material of the Ebola virus was not sufficient to understand why and how the disease spread so rapidly. Anthropologists therefore looked to religious beliefs and practices and observed that some West African communities touch and hold the bodies of their deceased loved ones as part of religious and cultural rituals. A holistic approach to the Ebola epidemic acknowledged the impact of religious practices on health-related issues, and ultimately enabled more effective medical intervention (Wilkinson et al. 2017).

- Marriage is practiced in a variety of ways across cultures, and in some rural Tibetan communities, women marry multiple men at the same time. Most commonly, a woman will marry all of the brothers from one family. We call this practice fraternal polyandry. Anthropologists have examined this practice at length, and by examining the culture holistically, we understand that a variety of factors have led to its development (Starkweather and Hames 2012). In traditional Tibetan society, families prefer to keep their farms intact without splitting the land between children, and fraternal polyandry keeps the entire farm intact within the same family (Goldstein 1987). Here, our holistic approach has revealed connections between Tibetan ideas about families and wider economic and social practices.

Exercise 1B

Watch Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Ted Talk titled “The Urgency of Intersectionality” to better understand her groundbreaking framework.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- What does Crenshaw mean when she speaks about “frames”? How do these frames tangibly impact our cultural lives?

- What is the “problem” that Crenshaw proposes? How can a new concept (intersectionality) help us understand the reality of this problem?

1.9 Intersectionality and Holism

We can look at the work of UCLA Professor Kimberle Crenshaw to better understand certain aspects of the holistic approach as it relates to contemporary discussions surrounding race and racism in the United States. Crenshaw argues that while some American media narratives do bring the murders of unarmed Black men to light, American media and American society at large more often ignore or downplay the murders of unarmed Black women (the same is true of other injustices and mistreatment faced by Black American women). By examining this phenomenon holistically, anthropologists and social scientists understand that forms of adversity these women face are harder to address because both their race and gender intersect to create a type of marginalization that is unique. Black women in America are marginalized differently than Black men are and we cannot study the two trends in the same way; we must consider the way that beliefs about race and gender interact together in parts of American culture. Crenshaw calls this intersectionality whereby all of our different identities (our race, gender, class, nationality, ability, sexuality, etc.) intersect with one another in order to create unique lived experiences.

1.10 Worldview and Enculturation

When we take a holistic approach, we are examining the “whole” of something. The whole of our culture influences our worldview. Anthropologists are very interested in examining and understanding different people’s worldviews. Your worldview is the way that you view the world, including:

- Your understanding of “good” and “bad.”

- Your ideas of how people should behave.

- Your idea of what gender roles are.

- Your idea of what is “just” (“what constitutes justice”).

- Your understanding of history.

It is important to note that no two people possess perfectly identical worldviews, not even two members of the same culture. However, anthropologists know that worldviews are culturally specific; they are shaped by our cultural surroundings to a large extent. By holistically examining all of the elements that tie into a person’s life or into a cultural setting, we can better understand how different worldviews emerge. In this text, we’ll be examining a wide variety of different worldviews.

The process through which you learn your culture and worldview is called enculturation. You were likely enculturated through media such as TV and movies, as well as by a family, who taught you what “proper” behavior was, and by friends, who rewarded or “positively reinforced” some behaviors while discouraging or “negatively reinforcing” other ones. Your view of the world was likely also developed by medical experts who told you what was mentally and/or physically healthy and by religious leaders who made similar pronouncements.

Consider the following examples of the enculturation process:

- Human bodies are very diverse. Weight, skin tone, hair color, length, and texture all vary widely. From a medical standpoint, different heights and weights can all be equally healthy and normal. However, our ideas of what is “beautiful” and “attractive” are largely defined by powerful cultural trends that typically only promote one type of body as the “ideal” type. When we grow up in a society that consistently puts one form of beauty on magazine covers, in TV shows, and on children’s toys, then we are enculturated to value only one very small sampling of human bodies.

- People are not born with a preconceived notion of what “success” or “power” looks like. In fact, these concepts vary from generation to generation and from society to society. We learn culturally-specific ideas of success and power throughout our lives, as teachers, parents, religious leaders, media, mythology, and other widespread narratives define and reinforce these concepts.

With many of the key terms now clearly defined, we can turn our attention to a few major shifts and developments in the way anthropologists study magic, witchcraft, and religion that will inform the rest of this course.

1.11 Shifting Gears: Anthropology, History, and Colonialism

The actual “beginning” of anthropology is hard to identify because human beings have, to some extent, always been interested in studying each other. Long before anthropology was officially recognized as a field of study, early travel writers and philosophers from ancient societies all over the world studied and wrote about the diversity of human culture. (Guest 2020, 68). The value of anthropology became more pronounced during the era of European expansion from the 16th-20th centuries, as European countries strove to expand their political influence and control areas across the entire globe. In many cases however, European-run colonial governments struggled to control local populations (Wolf 1982). During this time, early anthropologists produced works that often assisted colonial governments in their missions (Kuper 2006).

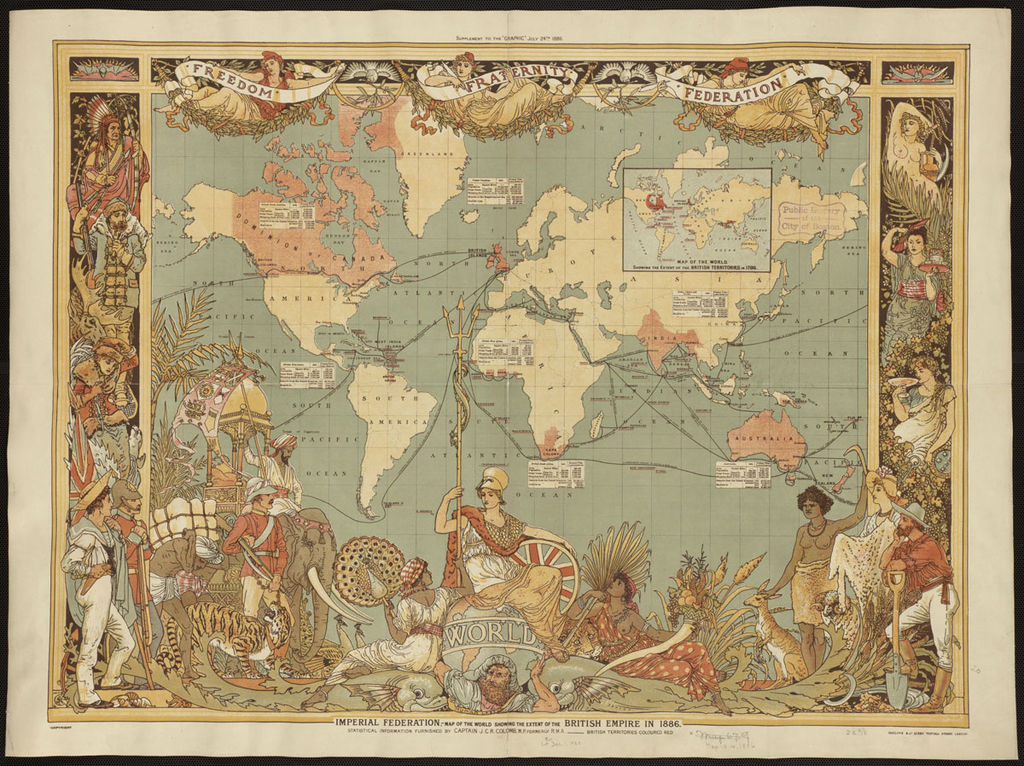

We use the word colonialism to refer to the control of people and their land by a foreign power. Colonialism has existed throughout the past and present to varying extents and in different forms. During the 16th-20th centuries, European powers sought to expand their political and economic control of various resources throughout the world: commodities like foodstuffs and other more exotic materials, strategic waterways and valuable trade routes, and in many cases, people. Often, colonial invaders, administrators, and rulers viewed native peoples, their practices, and even their basic human needs, as an obstacle to the success of the colonial undertaking. In many cases, these groups treated native people and their cultures as little more than resources to be enslaved, without equal standing or claim to human rights.

At this point, it may be useful to take a look at a world map and identify parts of the world that were colonized during the era of European expansion. Nearly the entire African continent was colonized, as was all of South America and the Pacific Islands. More than half of the Middle East and Asia was colonized by European countries during this time as well. As discussed above, early anthropologists and their “scientific studies” of human culture were involved at least indirectly in colonization efforts and in perpetuating uneven power dynamics during this period. The role of anthropology has certainly shifted since that time, but the colonial era is a critical part of the history of ideas we will encounter later in the text.

1.12 What Did Colonial Anthropologists Actually Do?

During this period, European anthropologists wrote and shared “scholarly works” they wrote about other cultures. These works may have assisted colonial governments in their efforts by:

- Serving as propaganda that presented native peoples as “savage” or less-than-human, while simultaneously serving as propaganda that held Europeans up to be fundamentally different (“civilized”). When these early anthropologists were viewed as “experts,” they were taken at their word by European audiences. When anthropologists produced accounts that were steeped in racism, these accounts served to justify the abusive control that European powers sought to keep over the rest of the world (Crewe and Axelby 2014, 28-31; Kuper 2006, 111).

- Developing a hierarchy of cultural value. European anthropologists believed that their culture was, inherently, the “best” culture. They then strove to compare all other cultures against that standard in order to determine which people were more advanced than the rest. This logic is inherently flawed because the European standard of greatness is not a universal standard and these cultural hierarchies were not objective.

- Collecting census data. By surveying the number and types of people in each community, the colonial governments could better exercise control.

- Studying and learning the local culture and languages. It was easier to control a population if you could understand how they spoke to each other and about themselves.

- Studying and learning about local judicial systems so that the foreign governments could use them to better control the local population.

We call anthropologists of this era armchair anthropologists because they did not spend a great deal of time among the people whose cultures they studied (Guest 2020, 69). In fact, some never visited the people they wrote about at all. Armchair anthropologists would rely on information provided by missionaries, government officials, merchants, and travelers in the field; they would then combine these disparate observations to write articles and books about human cultural variation. As you can probably imagine, this type of research is often unreliable and did not actually reflect the real practices of the cultures it investigated. Similarly, cross-cultural patterns that these early anthropologists observed were often inaccurate.

Early anthropologists’ impact on the cultures they studied is hotly debated. While we know that anthropologists were offered funding and access to native lands during the era of European expansion (Guest 2020, 69; Crewe and Axelby 2014, 28-31; Kuper 2006, 113), and that many of these anthropologists marketed themselves as helpful to colonial governments in order to gain funding and other support (Kuper 2006, 94-114), the actual contribution that anthropology made to colonial rule is widely contested (Asad 1991). For example, anthropologist Adam Kuper argues that anthropologists were in fact mostly ignored by government officials as eccentrics while anthropologist Talal Asad argues that the contributions of early anthropologists were too specific to be helpful to colonial administrators.

Did anthropologists directly help colonial governments? This is unclear. But what is clear is that early anthropology was steeped in a worldview of white, European supremacy during its early development (Wolf 1982; Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva 2008, 18-19). Whether each individual anthropologist was assisting or resisting the colonial effort, they were working within a framework that constructed the world in terms of European whiteness (Said 2004, 1).

1.13 Cultural Relativism

Anthropologist Franz Boas developed the concept of cultural relativism in direct response to this kind of ethnocentric thinking. Cultural relativism is the principle that all cultural beliefs and practices are equally valid in their own context. In other words, to judge a culture other than your own based on the standards that you learned within your cultural setting is always a pointless exercise that is biased by ethnocentrism. Instead of judging from the perspective of an outsider, as early anthropologists did, we now strive to understand cultures on their own terms: through their own, culturally-specific logics.

To that end, throughout this text, we will present diverse cultural beliefs and practices, some of which are likely to be quite different from your own (including, for example, cannibalism and polygamy). You never have to agree with or even like these cultural practices, but you must strive to understand how they make sense to cultural insiders, in their own cultural context.

1.14 Engaging with Cultural Relativism: What is a “Liberated Woman?”

We can look at the example of a liberated woman to better understand how cultural relativism works. Many women’s liberation movements in the United States are of the view that a woman’s body is natural, not inherently sinful, and that the amount of clothing a woman wears should not determine whether she can be safe in public (Mascia-Lees 2010, 33-58).

This worldview makes sense in its own, culturally-specific context. However, there are many other forms of women’s liberation in the US and across the world that incorporate a different form of logic and, ultimately, arrive at a different conclusion. In some religious communities – including some Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities – a liberated woman is a woman who is freed from the male gaze. In this context, a woman who covers most of her body is not pressured to be judged by society or to look attractive to men. By this cultural perspective, true freedom is the freedom from showing one’s body (Abu-Lughod 2002, 787; Mascias-Lees 2010, 63-65).

While these two value systems seem contradictory, they both make equal sense in their own context and are both designed to achieve the same outcome. By practicing cultural relativism, we can move past the idea that these two cultural practices are mutually exclusive. Both cultural views address similar goals; they simply express the same cultural value in different ways.

In each case, deeply ingrained cultural preferences can limit a woman’s freedom of expression and nonconformity can even threaten her safety. A community – like many in the United States – that expects women to uncover may react with hostility toward a woman who fully covers. On the other hand, a community that expects women to cover – like parts of Indonesia or the United Arab Emirates – may be hostile toward a woman in a bikini. In both cases, women are expected to internalize a specific value system that makes sense in context and anthropologists can examine both to better understand the larger human experience.

Now, you’ll read the work of feminist anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod titled, “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?” Abu-Lughod addresses controversial issues surrounding the US invasion of the Middle East after 9/11. She also argues that different groups of women empower themselves in different ways and that when some American audiences judge other groups’ “liberation” through an ethnocentric lens, serious misunderstanding and conflict can result.

Exercise IC

Using your college library’s login, read Lila Abu-Lughod’s piece titled, “Do Muslim Women Need Saving?”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- Using specific examples from the text, how have the narratives about Muslim women been written without their consent or participation?

- What does Abu-Lughod mean when she calls the burqa a liberating invention?

- Do people in your community have free choice over what they wear in every situation? What parts of the body are expected to be covered? What parts of the body are expected to be revealed? Consider more than one gender in your response.

1.15 Participant Observation

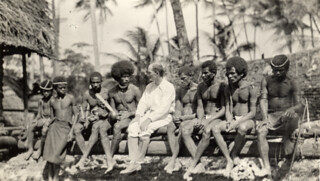

In 1914, an anthropologist named Bronislaw Malinowski was offered a position to briefly visit New Guinea (a British colony at the time). Malinowski was a citizen of Austria-Hungary and was studying in the UK. He planned to do the minimal amount of research that the dominant approach to anthropology that was required at the time (the armchair approach, discussed above).

Upon arrival in New Guinea, Malinowski learned that the First World War had broken out and that he was, essentially, “behind enemy lines.” Malinowski was required to stay in British territory as an “enemy of the state,” but he was hired to complete fieldwork while he lived among the Trobriand Islanders. Malinowski transformed fieldwork by intimately getting to know the community he studied in a manner that previous anthropologists had not.

After the end of the war, Malinowski returned to the UK with a powerful book about the cultural lives of people he had actually observed first-hand. He had also lived among them and known them as a participant in their daily lives and activities. Malinowski’s experiences led him to develop the fieldwork strategy known as participant observation that is critical to most anthropological research today.

The four steps of participant observation are:

- Stay for an extended period of time: This may seem obvious to us now, but it was groundbreaking at the time. Malinowski wanted to make sure that anthropologists spent years living among the people they were studying in order to have enough time to fully understand all elements of the culture.

- Learn the local language: If you are multilingual then you know that different languages lead to different ways of thinking. Malinowski realized that you can’t understand a community if you can’t learn how they speak about themselves and about the world.

- Explore the mundane imponderabilia: in other words, “make the strange familiar and make the familiar strange.” Anthropologists strive to make sense of cultural practices that seem “strange” while equally trying to identify what might be unique or “strange” from an outsider’s perspective in order to highlight what, exactly, is a social construct in our own cultures.

- “Get off the veranda:” Malinowski wanted anthropologists to leave their homes and actively participate in the cultural practices of the people they were studying (DeWalt 2011, 1-17). It is only by getting off the veranda and participating, while also observing, that we can ever fully know the people that we are studying.

Exercise ID

Anthropologists are required to learn the local language when engaging in fieldwork. Listen to NPR’s story titled, “A Man Finds An Explosive Emotion Locked In A Word” to understand how our languages shape our reality.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- How did language shape Rosaldo’s reality? How did the expansion of language help to transform his emotional state?

- How is grieving allowed in your own culture? How is it limited? Consider the range of allowed

emotional expression, length of mourning time, required activities, and restricted activities in your response.

1.16 Ethnography

Anthropologists produce ethnographies (written descriptions of a community or cultural practice). In order to produce a good ethnography, we need to be able to conduct participant observation while practicing cultural relativism. An anthropologist in the field will face a variety of challenges that will inhibit good ethnography, including:

- Understanding culturally-specific logic.

- Removing power for people to speak for themselves.

- Instinctual desire to measure the culture against your own.

The term “ethnography” is not only a term for the written work that an anthropologist produces after observing and participating in a culture. It is also a shorthand term used to describe the method of participant observation that Malinowski pioneered. Throughout this course, you will encounter the term “ethnography” as a way of describing both the product of an anthropologist’s fieldwork and the fieldwork method itself.

1.17 Emic and Etic Perspectives

A written ethnography presents a way of understanding a culture based on an anthropologist’s insights and experiences as a participant observer. However, as it turns out, there is more than one way to “understand” a culture. We will sometimes find it useful to distinguish two separate perspectives we use when studying cultures, each highlighting a fundamentally different way of viewing cultural beliefs and behaviors. Each of these perspectives has an important place in the anthropologist’s toolkit.

As you have learned, anthropological fieldwork involves immersing oneself in a group’s day-to-day activities, participating in their rituals, attending social gatherings, and conversing with cultural insiders. All of this is done with the goal of understanding the culture from the perspective of its actual members. To learn how cultural insiders see the world is to gain what we call an emic perspective. Another way to say this is that when we take an emic perspective, we are looking at the world around us through the eyes of a member of a particular culture, interpreting it in terms of their beliefs, preconceptions, and categories.

In contrast, another approach that anthropologists use when trying to gain an understanding of a culture is what we call an etic perspective. This term refers to a way of observing a culture without the preconceptions, attitudes, or cultural knowledge of its members. In other words, an etic perspective is supposed to be free of any cultural biases, even cultural insiders’ perspectives about their own reasons for doing what they do.

1.18 An Example of the Emic and Etic Perspectives: a Morning Meal

Kenneth Pike, a scholar who coined the terms “emic” and “etic” in the 1950s, provided an example of a group of biologically-related individuals gathered together, eating toasted bread and butter, scrambled eggs, and orange juice, shortly after sunrise (Mostowlansky and Rota 2020, 5-6). An anthropologist using an etic perspective to interpret this event might choose to focus on the quantity of calories, cholesterol, and carbohydrates each individual ingests during this event. An anthropologist using this (etic) perspective might also emphasize the way that daily feeding events like this one allow the members of a household to share information about their schedules over the next day and coordinate with one another before they separate to fulfill their economic, social, political, and familial responsibilities.

In other words, an etic perspective focuses on the observable functions of a practice – even one as simple as “breakfast.” It does not focus on what cultural insiders think of, what they care about, or how they describe this event when they reflect on it. When early anthropologists wrote about cultural practices among groups all over the world who they viewed as “primitive,” they tended to use an etic approach. Members of the cultures that these anthropologists wrote about would likely have explained their own beliefs in very different terms than armchair anthropologists did.

Looking at the same event described above from an emic perspective, by contrast would frame it as cultural insiders see it. To cultural insiders, this event is a type of event that is both familiar and meaningful, and even carries its own symbolic importance due to the specific cultural information they have come to possess through the process of enculturation. This event is breakfast – “the most important meal of the day!”

Of course, from an objective and unbiased standpoint, cultural insiders may be correct or incorrect in their attitude or their belief about breakfast and its importance. Most likely, they have plenty of other ideas or expectations or associations relating to breakfast that are unique to their specific culture. In fact, the very concept of breakfast may be unique to their culture, such that outsiders observing them eating might not have any preconceived notions or even a word for this particular behavior.

In short, when we discuss an emic perspective, we are referring to cultural insiders’ unique understanding of their own practices. Throughout this course, we will encounter instances where cultural insiders’ (emic) perspectives are critically important for us in order to understand why people make the choices they make.

1.19 Why Emic and Etic Perspectives Matter

Anthropological research conducted over centuries teaches us that an enormous and diverse range of worldviews have always existed, and continue to exist across human cultures. We should expect that not all cultures use similar categories, and what members of one culture see as beautiful, ethical, or valuable might differ significantly from how people in another culture assign these attributes to objects, actions, and ideas they encounter.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, one of the central goals of anthropology involves documenting and understanding these different cultural perspectives. To do so, we will often need to wear the lens of a cultural insider, taking on the emic perspective to the best of our ability. At the same time, there will also be instances where cultural insiders understand their behaviors in ways that do not fully capture what we are really interested in. In these instances, it may not be enough to know how insiders explain or justify their own cultural practices. Instead, we may also want to consider factors that aren’t obvious or don’t seem important to cultural insiders. Such cases require us to use the etic perspective.

Again, neither one of these perspectives should be treated as superior; in fact, most of the situations we consider will require us to understand both emic and etic perspectives.

1.20 Remembering Emic and Etic

If you’re looking for a trick to remember the difference between emic and etic perspectives, consider the way that the word emic has the letters “m” and “e” in the word spelling the word, “me” and then you can remember the emic perspective is your own perspective. What this means is that when you grow up in your own culture, you, likely, understand why you practice certain holidays, why you dress a certain way, why you divide labor in a family differently than another culture might do it, and you can explain these things to outsiders if they’re visiting your culture and looking to learn about it. However, because everything in your culture might feel so normal and natural and obvious to you, you may not know what is unique or interesting about your culture. This is why we need outsiders to visit our cultures and observe them with an etic perspective. The etic perspective, or, the outsider’s perspective, can highlight what is unique about a culture from a new, alternative viewpoint.

1.21 A Final Note on Critical Thinking and Studying Anthropology

Education, including this class, is a part of the enculturation process (discussed above). Concepts are presented to us as facts in the classroom and we are expected to understand the material in the same way that our instructors understand the material. If you’ve ever felt frustrated by a teacher’s bias, then you know that there can be an inherent power imbalance in the education system: teachers have a great deal of power to influence their students’ understanding of the world around them (Freire 1972).

Educators have the power to:

- Identify and present information in a manner that we see fit

- Interpret the information in a way that is in line with our own worldview

- Encourage the reflection of our own worldviews in the grading process

Your instructors have culturally specific worldviews that can never fully be removed from the classroom. Your anthropology instructors strive to equalize this power imbalance as much as we possibly can by being transparent about our personal biases and by asking you, the student, to speak up and share your personal knowledge and experience (especially when it differs from our own).

The college classroom is the best place to learn how to think critically and you can achieve this by learning how to critically engage with academic arguments. Critical thinking is an essential skill that we work to help you develop. Critical thinking is the practice of examining evidence and using what you learn from it to reach a conclusion. By advancing your critical thinking skills, you’ll be able to better separate fact from fiction when watching, listening to, or reading news stories or arguments from politicians or from other powerful sources that wish to maintain power over you. When thinking critically, it’s essential to:

- Consider the speaker: What is their agenda? What are they trying to achieve? Do they want something from you?

- Consider the evidence presented: Is it reliable? How do you know?

- Consider your own knowledge: What has your experience been? What unique information do you possess about the issue at hand?

Then, finally, make up your own mind about the information presented. In your personal life, you should be able to do this with your teachers, news media, politicians, medical and religious experts. In this course we will work with you to help you critically examine the arguments presented by anthropologists so that you can decide, for yourself, which arguments are most valid and valuable.

The first step in understanding how to think critically is to remember that your instructors are also human beings with specific worldviews, and that Anthropology, like all of the social sciences, is based on debate and dialogue between social scientists’ different theories. It’s important that you understand that nothing we learn here is absolute, objective fact but, rather, our subject is made up of well-researched and developed arguments that rely on the arguments of social scientists who came before us. We will also be incorporating evidence from our own research and our own lived experiences in the material. Please consider all of this when critically engaging in the course material.

At the end of the semester, you should be able to:

- Critically examine the arguments of the social scientists we learn this semester

- Remember who made each argument because they are arguments and not absolute, objective fact (this is usually the hardest part of course, but we’ll support you to make it easier)

- Critically examine our arguments, consider our perspective as authors and anthropologists

- Listen to the contributions of your classmates who have equally valid knowledge and experiences to share

- Contribute to the dialogue yourself by offering “I statements” (please do not make claims in the classroom that you cannot, personally verify to be true)

- Come to your own conclusions based on all of these considerations

Exercise 1E: Journal Reflection

Reflect on the principle of cultural relativism and identify an occasion in your life where cultural relativism might have helped overcome a conflict. Explain how understanding another person’s worldview using their own, culturally specific logic can lead to a better understanding of the human experience.

Exercise 1F: Study Guide

Before moving on, ensure that you can define the following terms in your own words:

- Supernatural:

- Magic:

- Religion:

- Witchcraft:

- Anthropology

- Archaeology:

- Linguistics:

- Biological Anthropology:

- Cultural Anthropology:

- Semiotics

- Holism:

- Intersectionality:

- Worldview:

- Culturally-specific

- Enculturation:

- Critical Thinking:

- Ethnography:

- Etic:

- Emic:

- Colonialism

- Participant Observation :

- “Mundane Imponderabilia:”

- Cultural Relativism:

- Ethnocentrism:

- Culture:

- Armchair Anthropology:

What are the 4 steps of participant observation?

Ensure that you can briefly summarize the arguments of these social scientists:

- Franz Boas

- Kimberlé Crenshaw

- Lila Abu-Lughod

- Bronislaw Malinowski

- Kenneth Pike

- Jason De León

- Renato Rosaldo

Chapter 1 Works Cited

- Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2002. Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others. American Anthropologist 104(3), pp. 783-790.

- Asad, Talal. 1991. “From the History of Colonial Anthropology to the Anthropology of Western Hegemony.” Colonial Situations: Essays on the Contextualization of Ethnographic Knowledge. Ed. George Stocking. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, pp 314-324.

- Boas, Franz. The Mind of Primitive Man. Forgotten Books, 2015.

- Crewe, Emma and Richard Axelby. 2014. “Anthropologists Engaged.” Anthropology and Development: Culture, Morality and Politics in a Globalised World, by Emma Crewe and Richard Axelby. Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 28–31.

- Dewalt, Billie R., and Kathleen M. Dewalt. Participant Observation: a Guide for Fieldworkers. Md., 2011.

- Frankle, R. L. (2005). Anthropology of Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft. Retrieved 2020.

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Education, 1972.

- Goldstein, Melvyn. “Fraternal Polyandry: When Brothers Share a Wife.” Natural History, 1987, pp. 39–48.

- Graeber, David. Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: the False Coin of Our Own Dreams. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

- Guest, Kenneth J. 2020. Anthropology for the 21st Century.” Essentials of Cultural Anthropology: a Toolkit for a Global Age. W. W. Norton and Company, pp. 9–69.

- Kuper, Adam. Anthropology and Anthropologists: the Modern British School. Routledge, 2006.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw, et al. A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term. Stanford University Press, 1989.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: an Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978.

- Mascia-Lees, Frances E. 2010. “The Politics of Anthropology.” Gender and Difference in a Globalizing World: Twenty-First-Century Anthropology, by Frances E. Mascia-Lees, Waveland Press Inc, pp. 69–70-212.

- Mostowlansky, T. & A. Rota. 2020. Emic and etic. In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology (eds) F. Stein, S. Lazar, M. Candea, H. Diemberger, J. Robbins, A. Sanchez & R. Stasch. http://doi.org/10.29164/20emicetic

- Said, Edward W. 2004. “Imaginative Geography and Its Representations.” Orientalism, Vintage Books, pp. 49–72.

- Slocum, Sally. “Woman the Gatherer: Male Bias in Anthropology.” Toward an Anthropology of Women, 1975.

- Starkweather, K.E., Hames, R. A Survey of Non-Classical Polyandry. Hum Nat 23, 149–172 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-012-9144-x

- Wilkinson, A., Parker, M., Martineau, F., & Leach, M. (2017). Engaging ‘communities’: anthropological insights from the West African Ebola epidemic. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 372(1721), 20160305. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0305

- Wolf, E. Europe and the People without History. University of California Press, 1982.

- Zuberi, Tukufu and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. 2008. “Toward A Definition of White Logic and White Methods .” White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 18–19.

Chapter 1 Suggestions for further reading:

- “Chapter 4.” We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda, by Philip Gourevitch, Picador/Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2004.

- Earle, T. 1997. How Chiefs Come to Power: the Political Economy in Prehistory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Lindenbaum, Shirley. “An Annotated History of Kuru.” Medicine Anthropology Theory | An Open-Access Journal in the Anthropology of Health, Illness, and Medicine, vol. 2, no. 1, 2015, p. 95., doi:10.17157/mat.2.1.217.

- “The Notion of Witchcraft Explains Unfortunate Events.” Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande, by E. E. Evans-Pritchard and Eva Gillies, Clarendon Press, 2014.

- “Production.” Sweetness and Power: the Place of Sugar in Modern History, by Sidney Winfried Mintz, Penguin Books, 2018, pp. 20–73.

- “Toward and Interpretive Theory of Culture.” The Interpretation of Cultures, by Clifford Geertz, Basic Books, 1972.

Written by Amanda Zunner-Keating and Ben Shepard. Edited by Oscar Hernández, Ben Shepard, Laurie Solis, Brian Pierson, Madlen Avetyan, and Amanda Zunner-Keating. Special thanks to Jennifer Campbell for curating photos; and to Melody Yeager-Struthers for organizing our resources. Student editing by Renee Rubanowitz and Alexa Zysman. Layout by Amanda Zunner-Keating and Madlen Avetyan. Audio recording by Amanda Zunner-Keating.

NPR links on this are linked NPR’s website with permission from NPR. All NPR content (audio, text, photographs, graphics, videos) is protected by copyright in the U.S. and other countries. For more, visit NPR’s Rights and Permissions website.