10 Comparative Religion

Chapter 10 audio be accessed on Soundcloud. Instructor resources are available on Canvas Commons.

Chapter 10 Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Compare and contrast the beliefs of the world’s major religions.

- Connect modern religious beliefs with historical and political changes throughout human history.

- Distinguish the terms “religion” and “cult” and critique widespread uses of the “cult” concept.

10.1 Cross-cultural Examination of Religion

A tool that anthropologists use to closely examine cultural adaptations, cultural evolution, and the migration of culture, is the cross-cultural approach. The cross-cultural approach compares more than one cultural belief, tradition, or practice in order to identify differences and similarities that exist across groups. As we have seen in this course, anthropologists place no more importance on the major religions of the world today than we do on the ones practiced by small or isolated or even ancient groups. Because we set out to document and understand religious variation among humans, it only makes sense that we would want to examine the full range of that variation, not just a few of the most widespread examples. However, we also recognize that there is some value to singling out the major world religions in order to identify traits they have in common while similarly recognizing the major differences that arose due to environmental factors, historical events, etc. The following chapter will compare and contrast the beliefs, myths, and traditions of the world’s major religions in an attempt to offer a holistic picture of the world’s dominating belief systems.

Throughout this chapter it’s important to be able to separate your own, particularly religious beliefs from the chapter content and to look at religions objectively. Do not apply your own, culturally-specific idea of ultimate “truth” to the other religious belief systems that we will examine here; strive to think like an anthropologist and employ cultural relativism.

10.2 Religions Change Over Time

In “The Essentials of Hinduism,” Swami Bhaskarananda writes,

“Any ancient religion can be compared to the attic of an old home. Unless the attic is regularly cleaned, it gathers dust and cobwebs and eventually becomes unusable. Similarly, if a religion cannot be updated or cleaned from time to time, it loses its usefulness and cannot relate anymore to changed times and people.”

Here, Swami Bhaskarananda is making an important point: religions must adapt to changing times, environments, political events, and social contexts in order to remain relevant in the minds of adherents. This is precisely what we will examine together throughout this chapter. In the case of each major world religion, we will examine the cultural events that shaped the religion as we know it today and we will identify the cultural context that allows the religion to maintain relevance.

Remember that anthropologists embrace two prevailing theoretical approaches towards the development of world religions over time:

- The evolutionary approach argues that world religions evolved over time to meet culturally different needs and historical changing needs. The evolutionary approach comes initially from Edward Burnett Tylor, who argued that religions evolve in a linear manner in one inevitable direction. Of course, we know that religions don’t actually evolve in a linear manner, but religions do change and adapt over time.

- The other major approach is the diffusionist approach. Diffusionists argue that religions spread, or diffuse, across the globe because people spread them. We do so by sharing our beliefs and practices with others, who sometimes adopt those beliefs and practices as their own. We also bring our beliefs and practices with us when we move to new places. Today, diffusion is always happening, and with globalization and mass migration, world religions are spreading more than ever. With technology, we are able to share our religious and spiritual world views more than ever. The diffusionist approach is often criticized because it over-simplifies the way that religions spread. In its extreme form, diffusionism implies that spiritual innovation never happens. Rather, one or two civilizations came up with religious ideas and spread these ideas to everyone else. However, innovation does happen.

Both approaches are true to an extent; religion is ever-changing and is always diffusing across the globe.

10.3 The First Religion

Students often ask, “Who were the first humans to have religion?” But, in fact, religion may predate humanity as we know it. How do we know this? Human ancestors are called hominins. Two species, dating back 500,000-30,000 years ago show evidence of intentional burial.

Homo heidelbergensis buried their dead in manually-dug pits with symbolic items such as a pink handaxe that would shatter if used. Neanderthals also buried their dead in specific body positions with symbolic artwork and grave goods. Since these hominins had brains the size of ours (or in some cases, even larger) and the capacity for language and dreams, it is proposed that they also could have had the first ideas of spiritualism or an afterlife. This leads anthropologists to ask: was this burial ritual an early form of religion?

This practice may signify a form of appreciation of their loved ones, or perhaps it reflects an idea that the dead might need items in the afterlife. As you already understand, burial rituals (death rituals) are central to religion and symbolic gestures are a key component of culture. In this way, the argument can be made that religion existed on Earth before the evolution of modern humans.

Exercise 10A

For more on the fascinating burial practices of our human ancestors, read “Who First Buried the Dead?” by Paige Madison.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- Why is it important to understand how human ancestors treated the dead? What does this say about our evolution?

- What signs do archeologists look for when determining how the dead were treated?

10.4 Animism

In Chapter 3, we learned that Sir Edward Burnett Tylor used the term “animism” to describe what he viewed as a fundamental attribute of all religious belief systems. Tylor adapted the term from the latin word anima, meaning spirit. Broadly speaking, his animism concept refers to a belief in “souls and other spiritual beings” (Tylor 1889). However, we may actually be able to add a little more detail to that rather broad definition.

To animists, people are more than just our bodies: more than bone, muscle, bacteria, and organic tissue. And to be clear, contemporary scientific perspectives define an individual human being in exactly this way; we are a collection of physical structures connected together to produce our consciousness and to store the information, memories, physical tendencies, tastes, and instincts that make us each who we are. For animists, however, there is a supernatural, immaterial (non-physical) thing that defines each of us.

And just as importantly, for animists, it’s not necessarily just humans who possess souls or spirits. Animals, plants and other parts of our environment like rocks, trees, lakes, pieces of art, cars, and places might also contain souls or spirits, in which case they are treated not as inanimate things, but as persons. Another way to say this is that animists see personhood – the condition of being a person – as something that certain non-human organisms and objects can also have.

To be an animist, then, is to live in a world where not only humans, but other things like animals, trees, rivers, and mountains are also conscious of their surroundings. In this worldview, anything with a soul or spirit can also possess a consciousness, opinions, desires, and even the ability to act according to its own will.

In her discussion of animism in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Katherine Swancutt (2019) provides an example of animist beliefs among Yup’ik groups in the Russian Far East and Alaska:

“Yup’ik residents of the Bering Sea coast consider that the ocean has eyes, sees everything, and does not like it when persons fail to follow the traditional abstinence practice of avoiding the waterfront after a birth, death, illness, miscarriage, or first menstruation (Fienup-Riordan & Carmack 2011, 269). Since the ocean brings disasters on people when it is upset, Yup’ik consider that it is best to wait until early spring before visiting it after one of these events. Spring is the season when grebes arrive and defecate in the water; it is also when ringed seals come and their blood soaks the ocean as predators attack. According to Yup’ik hunters, these events make ‘the makuat [ocean’s eyes] close and become blind’ so that the hunters can safely approach the waterfront again (Fienup-Riordan & Carmack 2011, 270).”

It is clear from this example that there are important implications of animist beliefs. Yup’ik people do believe that the Bering Sea has a soul, but this also means they view it as able to perceive when they break certain rules. Moreover, it dislikes when people do so, and it has the ability to act if it is offended.

Importantly, animism is not one specific religion. Rather, the term refers to an attribute that many religious traditions share. That being said, animism will manifest in unique ways within the diverse belief systems studied by anthropologists. Ethnographic study has revealed that groups may not agree on exactly what types of entities possess souls or on the specific details of what a soul entails , where it originates , and what it can do within the spirit realm or in reality.

10.5 Mesopotamian Religion and Judaism

When we try to identify the “first” religion, it can be quite challenging since each element of our modern definition of “religion” has evolved differently across cultures and throughout human and pre-human history. For this reason, it makes sense to next focus on the first written religion. With the emergence of the first written language, humans began to record their religious stories and ritual guidelines; this written form of religion offers anthropologists and archeologists clear evidence to examine.

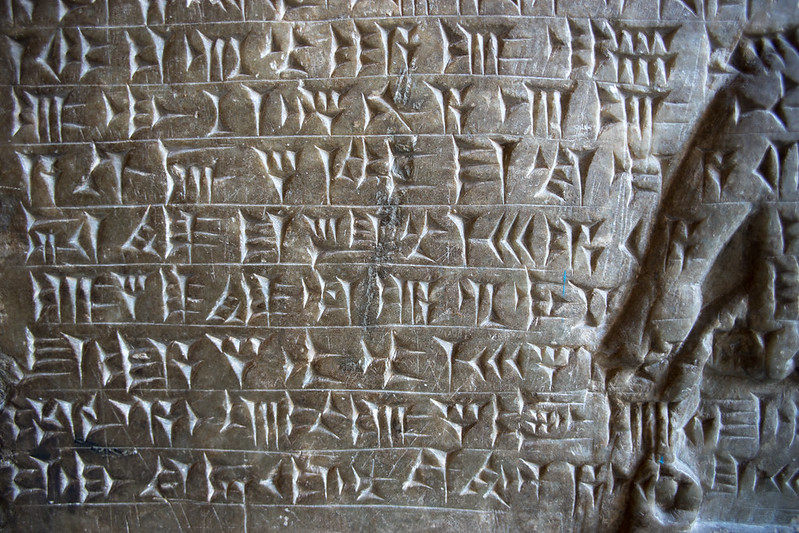

The Mesopotamians – a civilization that existed within the borders of modern day Iraq – were the first human civilization to develop a written language. It is called “cuneiform”, and it was developed about 3200 BCE. The clay tablets which contained cuneiform writing are well preserved and are continuously being discovered. Anthropologists and archeologists can read what the ancient Mesopotamians wrote about their spiritual worldviews which offers a helpful insight into the first forms of human religion (Cole 2012, 8).

A major religious text of the ancient Mesopotamians was called the Enuma Elish. The Enuma Elish is the creation story of ancient Mesopotamian society and it tells a story about a supreme god who created humans in order to serve the divine (Lambert 2013). Mesopotamian religion was polythesitic (the belief in multiple divine beings); the Mesopotamians believed their gods physically lived in ziggurats, or large temples that were built by communities. For this reason ziggurats were built to be huge and ornate. See Western Civilizations Vol. 1 pg 14 for more information on Mesopotamian religion (Cole 2012, 14).

Anthropologists closely examine myths in order to better understand a people’s worldview, and we compare and contrast myths in order to identify similarities and differences across cultures. Arguably, the most well-known Mesopotamian myth is “ The Epic of Gilgamesh”, which was written in 2100 BCE. “The Epic of Gilgamesh” tells many stories about a demigod on great journeys. However, of particular interest, is the great flood story within the epic. The great flood story told in Gilgamesh is nearly identical to the story of Noah’s Ark from the ancient Hebrew texts that are now embraced by modern Jews, Muslims, and Christians. Assyriologist Andrew George translated the epic to English and argues that the Mesopotamian flood story is so identical to the Biblical story of Noah that we must conclude that the two stories are related.

So, how could these two different religious traditions have the exact same myth? The answer is: both religious traditions emerged from the same part of the world at the same time. Let’s closely examine this.

We call three of world’s major religions – Judaism, Islam, and Christianity – the “Abrahamic religions” because they each identify as originating from Abraham (a foundational figure from the ancient texts of these religions).

Abraham is believed to have initially founded Judaism by entering his people into a covenant with God. He is believed to have actually existed by some scholars while others believe that he was written as a character to reflect the lives of many people who had lived during his time (Segal 2002). In either case, Abraham’s story tells us that he was born in the capital of Mesopotamia in 1700 BCE. So, based on the location and time of his birth, upbringing, and emergence as a religious leader, we can already understand that Abraham’s religious ideals were largely shaped by the Ancient Mesopotamian culture within which he was originally from (or, if he is a character written by a group of people, those writers were living near Ancient Mesopotamia at the time of the writing). Whether Abraham was actually one person or if he was written by a collection of people living in the region – the writers of early Hebrew texts would have been upper-class citizens, which means that they would have been well-educated in traditional Mesopotamian stories (Boadt 1984).

This is why Mesopotamian stories are largely identical to the Old Testament of the Bible, the Tanakh, or the Torah (Boadt 1984). There are a lot of similarities when comparing the two religions. Consider that both of these religions each:

- Discuss a “primeval sea” that existed before creation

- Believe that humans were fashioned from clay

- Tell flood story in which the earth and most of humanity is consumed by water

- Tell a plague story

The Judeo-Christain story about the creation of different languages is the “Tower of Babel”. The “Tower of Babel” is based on Mesopotamian ziggurats (citation needed). In the story, people built a tower to reach God in order to complain about the challenges of life. God gets angry at their hubris and destroys the tower . The people fall down from the tower and suddenly speak different languages. This way, they could no longer communicate among themselves to build another tower that would reach God. Mesopotamian scholars think that this was written by the Jews during a time when they were oppressed by Mesopotamian society. At the time, the Jews were a minority religion. They suffered by being marginalized, and their religion was viewed as a cult. The Jews saw the Mesopotamians using money on what they believed to be false gods and false prophets. They wrote the “Tower of Babel” as a form of political commentary of how Ziggurats were an overuse of funds and labor.

Exercise 10B

You can practice cuneiform in the kitchen. View The Getty’s page on cuneiform cookies for step-by-step instructions.

10.6 Hinduism

Hinduism is the only major world religion with no known founder and with no single holy text (Matthews 2007). Unlike Catholicism which has a singular authority (the Vatican) Hinduism is not defined by one ruling organization that defines the religion. In this way, Hinduism is considered to be a particularly adaptable religion whereby different regions of India will recognize, celebrate, and worship the divine in regionally specific ways. Hinduism is the most ancient major religion of the world and is the third largest, today.

Hindus believe in reincarnation (the idea that a soul is reborn into a new life after death) and in samsara (the cycle of life, death, and rebirth). During the cycle of life, karma determines a person’s next incarnation (this can be a human life or animal life). One’s actions and decisions in their current and even previous lives determines how one will be reborn in the next life. The goal of Hinduism is to free oneself from the cycle of death and rebirth in order to be free from the suffering of life; this goal is called “moksha.”

In Hinduism, religious followers strive to behave in an ethical way throughout their lifetimes and each individual follows the dharma, or ultimate cosmic truth. In this religion, different types of people have different types of responsibilities that they must meet in order to be in line with the dharma.

While Hinduism has many religious texts to refer to, the first emerged in 1500 BCE and is called the Rig Veda. The Rig Veda is one of the four traditions of Vedas and consists of mantras and myths about devas (gods). It provides information on ritual procedure by outlining hymns to praise the divine (Sarma 2008).

Another commonly referenced story of Hinduism is called the “Bhagavad Gita”. The “Bhagavad Gita”, is part of the epic Mahabharata and is told as a discourse between prince Arjuna and god Krishna. The story takes place during a war between the Pandava brothers and Kaurava brothers. It begins with Arjuna, one of the Pandava brothers, dropping his weapon and refusing to fight with his blood relatives (Sarma 2008).

As Arjuna approaches the conflict in his chariot, a major Hindu God, Krishna, appears to him disguised as the charioteer and explains the dharma to Arjuna , presenting the argument to engage in battle. While Arjuna expresses that he does not want to kill or hurt anyone, Krishna explains that the balance of the universe requires his action so that it can remain aligned. Krishna goes on to comfort Arjuna by assuring him that all souls live on after death, and that everyone’s fate is the result of their karma. Ultimately, the “Bhagavad Gita” is a spiritual dialogue and a conversation between the divine and humanity. Throughout the epic, Krishna tells Arjuna that humans were created to help the gods and that human life is eternal. This is why Krishna tells Arjuna to go to war in order to serve the divine.This story is also told as a lesson to the devotee for the need to uphold the societal structures, despite the personal reservations one may have, since these structures are part of the dharma.

Hindus believe in multiple gods and goddesses and these gods and goddesses can appear in different forms. Since Hindus believe that the divine is not limited to one form, Hinduism has been able to show a particular tolerance to other religious deities including the Buddha from Buddhism and Jesus from Christianity.

10.7 Ancient Egypt’s Brief Monotheism

The Ancient Egyptians were ruled by pharaohs who were viewed as divine, and therefore served as both political and religious leaders. Ancient Egyptian religion was, traditionally, polytheistic, meaning that they believed in multiple divine beings. However, the most interesting case to examine anthropologically is the case of the pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV) who temporarily forced Ancient Egypt to become monotheisticduring his reign. And, interestingly enough, some anthropologists and archeologists point to this historical occurrence as the beginning of permanent monotheism in other major world religions.

Akhenaten became a pharaoh at a young age after his father died. Before his death, Akhenaten’s father led his people in polytheistic worship but held the sun god, Aten, as his patron (favorite) deity. This sun god is also known as “Re” and was found in the Old Kingdom in cults that worshipped Amen-Re, long before Akhenaten rose to power. After Akhenaten ascended into his role as pharaoh, he outlawed the worship of any deities that were not Aten. Akhenaten destroyed temples and fired priests who served any deity that was not Aten. This is an early example of large-scale monotheism in the Ancient world. This revolution was not met with support from most of Akhenaten’s subjects, since it radically affected peasants’ and everyday people’s culture, religion, customs and wealth. Akhenaten was regarded as a heretic after his death, and under the pharaoh Tutankhamun polytheism and the traditional religious practices were restored.

Interestingly enough, Akhenaten’s monotheism may have had an influence upon the monotheism of modern Judaism (and, subsequently, modern Christianity and Islam). Moses, a central Biblical figure (important today to the Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) is believed to have lived in Egypt during or shortly after the reign of Akhenaten. As is true with many religious figures, we are not sure if Moses historically existed as one man or if he was written as a compilation reflecting many who lived at the same time. In either case, the ideologies that were developed during this time were influenced by Egyptian events.

It’s believed that Moses established the 10 Commandments (a set of rules defining ethics and worship in the Abhrahamic religions). It’s interesting to note that the first commandment tells followers that there is only one god. As the first commandment, this monotheistic statement largely defined the structure and values of the Abrahamic religions moving forward. The fact that one of the commandments states that “thou shall worship no other gods before me” points to a shift from polytheism to monotheism, suggesting that Moses and the ancient Hebrews accepted polyteistic traditions before this rule was put into place. Scholars have found connections between Egyptian wisdom instructions and the biblical books of Proverbs (from the Instruction of Ptah-hotep), Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Psalms, and Job. For example, there are strong parallels between the Hymn to the Aten and the Psalm 104 in the Bible.

Primary Reading: Psalm 104

He set the earth on its foundations;

it can never be moved.

6 You covered it with the watery depths as with a garment;

the waters stood above the mountains.

7 But at your rebuke the waters fled,

at the sound of your thunder they took to flight;

8 they flowed over the mountains,

they went down into the valleys,

to the place you assigned for them.

9 You set a boundary they cannot cross;

never again will they cover the earth.

10 He makes springs pour water into the ravines;

it flows between the mountains.

11 They give water to all the beasts of the field;

the wild donkeys quench their thirst.

12 The birds of the sky nest by the waters;

they sing among the branches.

13 He waters the mountains from his upper chambers;

the land is satisfied by the fruit of his work.

14 He makes grass grow for the cattle,

and plants for people to cultivate—

bringing forth food from the earth:

15 wine that gladdens human hearts,

oil to make their faces shine,

and bread that sustains their hearts.

16 The trees of the Lord are well watered,

the cedars of Lebanon that he planted.

17 There the birds make their nests;

the stork has its home in the junipers.

18 The high mountains belong to the wild goats;

the crags are a refuge for the hyrax.

Primary Reading: Hymn to the Aten

How manifold it is, what thou hast made!

They are hidden from the face (of man).

O sole god, like whom there is no other!

Thou didst create the world according to thy desire,

Whilst thou wert alone: All men, cattle, and wild beasts,

Whatever is on Earth, going upon (its) feet,

And what is on high, flying with its wings.

The countries of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt,

Thou settest every man in his place,

Thou suppliest their necessities:

Everyone has his food, and his time of life is reckoned.

Their tongues are separate in speech,

And their natures as well;

Their skins are distinguished,

As thou distinguishest the foreign peoples.

Thou makest a Nile in the underworld,

Thou bringest forth as thou desirest

To maintain the people (of Egypt)

According as thou madest them for thyself,

The lord of all of them, wearying (himself) with them,

The lord of every land, rising for them,

The Aton of the day, great of majesty.[7]

10.8 The Influence of Zoroastrianism

Ancient Persian civilization traded extensively with Ancient Hindu civilizations and, as a result, the two cultures influenced each other to adopt certain practices from the other. Interestingly enough, the philosophies of Ancient Persian society similarly spread across the globe to heavily influence the Abrahamic religions, as well.

In Ancient Persia, around 2000 BCE, a prophet named Zoroaster is believed to have been born. The stories surrounding Zoroaster tell us that he was highly critical of inequality in his society and that he advocated for a more egalitarian society (Cole 2012, 50).

Today, Zoroastrianism is a religion that is still practiced; the largest percentage of Zoroastrians live in Iran while the second largest group live and practice in Los Angeles, California. Members of the religion describe the faith as monotheistic because they only worship one divine being: a perfectly good and all-knowing god. However, Zoroastrianism also believes in a very powerful, evil being who is in battle with the all-good divine being. Anthropologists and scholars of religion call this phenomenon dualism: a religious tradition that believes in two opposing forces, often cosmic and eternal (Oxtoby 2002).

Zoroastrianism was the first religion to establish the idea of an all-good god and an all-evil being with which the all-good being is at war with. This worldview establishes the idea that human beings are engaged in a cosmic battle between good and evil and that human beings have the responsibility to choose sides.

Religious scholars largely agree that the concept of “Satan” evolved from this Zoroastrian concept (Oxtoby 2002). Biblical texts do not initially mention a devil figure and the idea of a purely evil being who is external from God. Instead, this idea first emerged during a period when Ancient Persian civilizations were influencing Hebrew and Judaic Biblical writings (Cole 2012, 51-3).

Interestingly, Zoroastrians believe in the concept of “dharma” similar to the Hindu idea. At the same time, Zoroastrianism calls for morality through action, which is uniquely different from Hinduism.

10.9 Buddhism

It’s believed that the story of the Buddha begins in the year 560 BCE in a region that is now called Nepal, a region that was part of an ancient Hindu society at the time. A figure called Queen Maya was believed to have had a dream of a white elephant informing her that she was pregnant. Upon calling a diviner to interpret the dream, the diviner told her that she would have a son who would either become a great spiritual leader or a great king. As the child’s father was already a King, the couple expressed a preference for their child to become a great king. In response, the diviner told the couple that they needed to shield their son from all suffering in order to prevent him from taking the path of spiritual leadership.

Queen Maya gave birth to her son Siddhartha, and shortly after giving birth she died. The king and Siddhartha’s adoptive mother raised him to be completely shielded from all types of suffering throughout his young life until, one day, the young boy asked to leave the palace and see the world. His parents allowed him to briefly leave the palace; during this time he witnessed 4 sights:

- Siddhartha saw a sick person who was suffering. Before this moment, Siddhartha did not know about illness.

- Siddhartha then saw an old person and was shocked because he had never before realized that people grow weaker as they age.

- Then, Siddhartha saw a dead body and was horrified because he had not previously been made aware of death.

- Finally, amidst all of this shock and suffering, Siddhartha witnessed a monk peacefully meditating. Siddhartha resolved to enter a journey of spirituality like this monk in order to find a solution to stop the suffering of people.

So, the story goes, that Siddhartha left the palace and studied a variety of spiritual movements. He first lived the ascetic life as a beggar (a strict life with no pleasures or indulgence) and did not reach enlightenment. He then lived a life of extreme indulgence but also could not reach enlightenment. Finally, Siddhartha sat below a Bodhi tree and realized that neither full sacrifice nor full indulgence is the key to enlightenment. Rather, Siddhartha realized “The Middle Way” is the path to becoming free from suffering. In this moment, Siddhartha became The Buddha, the Enlightened one. Over the course of centuries, followers of the Buddha developed core beliefs for how to achieve Enlightenment along the Middle Way.

The core beliefs of Buddhism include the Four Noble Truths, which are:

- All of life is suffering

- We suffer because we desire and cling to ideas, people, things, etc.

- Only by extinguishing desire can we stop suffering

- There are eight ways to end desire, called The Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path encourages:

- Right understanding

- Right thought

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right mindfulness

- Right concentration

Please note that The Buddha, if he existed as the story is told, never wrote anything down. He similarly never claimed to be a God or divine being. The Buddha’s religion, Buddhism, is closely related to Hinduism as Siddhartha was born and raised in the Hindu tradition. Prince Siddhartha was a member of the Kshatriya caste and until leaving the palace he fulfilled his duties according to the Brahmanic custom by being a devout student, then marrying a neighboring princess and having a son (Matthews 2007).

10.10 Christianity

Roughly 560 years after the Buddha is believed to have been born in India, a new religious figure named Jesus is believed to have been born in the year 4 CE in Bethlehem (a city in modern-day Palestine). It’s interesting to note that the stories surrounding both Jesus and Buddha originated along the Silk Road (a trade route that connects all of Eurasia and played a role in the spread of culture and ideas across cultures).

The story of Jesus tells us that he was born and raised in Palestine under occupation by the Roman Empire. Roman-ruled-Palestine was a territorial society where people often suffered under strict military rule and were stratified into strict class groups. As many suffered under Roman oppression, Jesus advocated for a more egalitarian society and was executed for undermining the powerful Roman rule.

One of the radical ideas developed during this time was that humans could have a personal relationship with God, and they no longer had to go through temples to reach God. This belief is a defining characteristic of Christianity and was innovated during the time of Jesus. Similarly, believers of this era established the central Christian value of forgiveness: the idea that Jesus died to forgive humanity of their sins and that, therefore, humans should emulate the divine and forgive one another.

In Christianity, the firm belief in maintaining monotheism necessitates that God and Jesus must be the same entity, thus allowing Christians to continue to worship Jesus while still only honoring one divine being.

Exercise 10C

For a deeper historical understanding of the culture that developed Christianity, read Bart Erhman’s interview that addresses: “If Jesus Never Called Himself God, How Did He Become One?”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- How did the legacy of Jesus change throughout human history? What does this tell us about changing cultural needs?

- What political and cultural events impacted the evolution of this religion?

10.11 Weber and the Protestant Work Ethic

Religion impacts many facets of a culture and society. Since Anthropology employs a holistic approach to understanding culture, this approach can be used to examine the way that Christianity has impacted other elements of modern Western culture. German Sociologist and economist Max Weber (1864 – 1920) argued in 1904 that Protestantism (a mainstream form of Christianity) and capitalism are such uniquely compatible worldviews that each augmented the other’s influence upon Euro-American civilization and led to the establishment of each as the dominating characteristics of much of the “western” world (Weber 2001). These arguments are outlined in his work, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” and we refer to the idea as the Protestant Work Ethic.

Before we can work through Weber’s arguments, we need to briefly clarify the different sects of Christianity. While the terms “Catholic” and “Christian” are often colloquially used to refer to different religions, Catholics are, actually, a form of Christianity. And, typically, when people use the term “Christian” in a colloquial sense in the United States, they are usually referring to “Protestants.”

Christianity is a major world religion that has three major subgroups: Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox. While Christianity has undergone a variety of transformations throughout history, it’s arguable that the greatest transformation followed Martin Luther’s 1517 “Ninety-Five Theses.” Luther composed his “Ninety-Five Theses” to critique the Catholic Church (the only official form of Christianity at the time). While the Catholic Church has changed a great deal since 1517, Luther’s public criticisms at the time centered around:

- The practice of buying divine forgiveness by giving money to the church

- The church’s celibacy requirements

- The worshiping of saints as near-gods

- The powerful position held by the Pope

As a result of Luther’s popularized demand for change, the 16th century subsequently witnessed a massive Protestant Reformation whereby new sects of Christianity emerged in opposition to Papal authority and the misguided beliefs and practices of the Catholic Church. The Protestant Reformation directly influenced the continual fracturing of Protestant Christian sects that still exist today, such as: Evangelical Christianity, Baptists, Lutherans, Quakers, Methodists, Anglicans, Non-Denominational Christians, Pentecostal, etc.

In Weber’s view, religious life before the Protestant Reformation saw poverty as a moral value. This is true in most religious traditions; Seeking wealth is frequently seen as a form of greed. Since most religions including Christianity discourage greed along a similar system of moral values, greed is viewed as sinful.

But, as Weber explains, the Protestant Reformation to a certain extent democratized how one can experience and connect with God, glorifying all forms of labor as a “calling” from God. In other words, before the Protestant Reformation, only those working in religious roles (priests) were viewed as doing “God’s work” but when Christianity started to view faith as more accessible to all types of people, anyone who worked hard was viewed as utilizing their gifts and talents given from God. As a result, making money was increasingly viewed as receiving God’s favor. The logic was: if you make a lot of money, then it must be because God favors your hard work.

This worldview became compatible with capitalism which is centered around the idea that, through market competition, the best ideas will always succeed. Capitalism tells workers that hard work will always be rewarded with wealth. Protestant Capitalism therefore asserted that accumulated wealth is a sign of how hardworking a person is, as well as how favored by God they are.

In Weber’s view, the cultural transformations within Christianity and the establishment of capitalism as the dominant economic system took a strong hold over Euro-American societies because they were compatible in their common idea that hard work leads to wealth and that wealth is a reflection of goodness. This becomes an incentive for Protestants to work as much as possible to earn as much capital as possible, proving their moral success and God’s favor for them.

Sociologist and philosopher Karl Marx argued that religion, as an ideology, maintains this system of inequality. It is here that Marx’s ideas are compatible with the arguments of Max Weber. As you already know, Weber argued that Protestantism and capitalism are two compatible ideologies because both view working-for-profit to be an inherent, moral value. In Marx’s view, those without wealth or power continue to work for low wages because they have internalized the idea that any type of work is, itself, an inherent moral value. Within a religious, capitalist culture, people work to benefit the rich because they believe that we will be rewarded in the afterlife. To summarize, Weber’s argument follows the following steps:

- Religious devotion usually leads people to reject worldly affairs (wealth, possessions).

- The Protestant Reformation (16th century, Martin Luther) led to many Christians glorifying their work and their wealth . This social schism rejected traditional ideas surrounding knowledge, power, and spirituality.

- Hard work was now viewed as “sacred”, a divine calling by God for people to fulfill their purpose.

- Work was also now a dutiful service to society, and anyone not working was not obeying God’s will for them.

- This new attitude allowed a desire for wealth.

- This idea overcomes previous issues regarding wage and time

- Pre-capitalist workers were unwilling to work more hours after reaching their desired income.

- Capitalist workers are willing to work more hours if they are paid a high wage

- In Weber’s view, this was not a uniquely “Western” trend – but the two cultural forces are so compatible that both Protestantism and capitalism flourish. The two established themselves as the dominating forces in both the United States and in Europe.

Christianity is a diverse religion with an enormous global following and there is no singular way to define that religion, much like all other faiths which cannot be simplified. We can, however, point to the rising popularity of “prosperity preachers” in Christian spheres to illustrate Weber’s points. Prosperity preachers are religious leaders who are, typically, wealthy and who believe that God makes good and pious people wealthy and successful. Within this religious worldview, sick or poor people can overcome their disease and poverty by increasing their faith and that, in exchange, their god will reward them financially and heal them. In some of these movements, followers are told that, if they donate money to the preacher or to the church, then they will be rewarded with more wealth.

10.12 Islam

In Islam, followers believe that God sends signs to humanity intended to remind us of our obligations to live a good and pious life. In this religious tradition, God commanded a series of prophets starting with Abraham to help guide humanity in a righteous path. It is believed that since we continuously forget our obligations to each other, the planet, and to God, God continued to command multiple people to help get humanity back on the right track.

Islam in Arabic means “to submit” to God and Muslims are “those who submit” to God. Followers of Islam, believe that Adam was the first prophet, followed by Noah, and later Abraham who submitted to the One God and engaged in a covenental relationship with Him to lead his people towards God. Abraham was followed by many other prophets including Moses (a shared prophet among Jewish people) and Jesus (a shared figure among Christians). In addition, Muslims also believe that God’s final prophet named Muhammad gave humanity a clear and final set of guiding principles intended to glorify God (Ayoub 2002).

Muhammad was born in the year 571 CE in Saudi Arabia. It’s believed that he was an illiterate man who entered a cave to pray and that, suddenly, the Angel Gabriel appeared to him and told him to “recite!” Over the subsequent 23 years, Muhammad wrote the words of the Qur’an, the holy text of Islam. It’s believed that, because Muhammad wrote the Qur’an in Arabic, that reading the text in Arabic is akin to literally reading the word of God (this is unlike most other world religious texts which have been translated into multiple languages over time).

There are 5 pillars of Islam:

- Faith, the monotheistic idea that there is no God but one God and that Muhammad is God’s favored and final prophet.

- Prayer, which requires followers to pray 3 or 5 times a day depending on whether one is Sunni or Shia.

- Alms-giving, where all Muslims donate a portion of their income to charity.

- Fasting, when Muslims do not eat or drink from sun up to sun down during the month of Ramadan.

- Pilgrimage, where Muslims are required to visit the holy site of Mecca once in their lives, which is called the Hajj.

As is commonly discussed, it’s forbidden to depict Muhammad in the Muslim tradition. This rule is held in Islamic culture as an attempt to prevent the idolization or mischaracterization of their holy person. Similarly, drawing or making statues of Jesus, Mary, or Moses, etc. are also forbidden and considered to be idolatry in the Muslim tradition.

10.13 “Cults”

Although this chapter mainly focuses on religious groups who present themselves as inheritors of ancient traditions and have followers numbering in the millions, we should also stop to consider a type of religion that tends to be smaller and younger. The groups in question – those known in public discourse as “cults”– are of considerable importance for how we think about religious variation today.

10.14 What’s in a name?

Like the terms “religion” or “culture,” “cult” is a difficult concept to pin down. You may feel that you simply know one when you see it, but we will need a better definition than that to have a productive discussion. After all, it seems unlikely that every other student in your class understands the term in exactly the same way as you. Because a “cult” is such a difficult thing to define, it can be difficult to distinguish these groups from “conventional” religions. Groups identified as religions or cults both use rituals, sacred spaces, and symbols to create a strong sense of common identity and shared belief among their members. Both also involve beliefs in the supernatural (although they do not always acknowledge the supernatural nature of their beliefs).

One factor that separates “cults” from “religions” is how people perceive them within cultural settings where they exist (Melton 2004). Consider the term religion; everyone within a particular society might not share the beliefs and practices of religions practiced within their cultural surroundings, but they likely don’t view the groups they call “religions” to be transgressive, dangerous, or threatening to the social order. In contrast, if your peers and family see that you are joining a group they consider a cult, they are likely to be worried, sad, confused, or even angry about your decision. They may even determine that you have been forced to join the so-called cult by means of manipulation and threats.

This is not dissimilar from the “witchcraft accusation” as described in Chapter 5: the term “cult” can be used as an accusation intended to discredit the spiritual movement/beliefs of a group. That being said, anthropologists, psychologists, and all social scientists do recognize that some religious movements are harmful or abusive. The distinction between a genuinely dangerous spiritual movement and an unpopular spiritual movement is an important distinction to make when analyzing modern religious trends.

While cultural insiders understand “religions” to be harmless and non-threatening, they usually view the groups they label as “cults” to be “abnormal” within their cultural surroundings. The term “cult” has taken on a negative connotation in the public eye for describing extremist religious sects that often separate themselves from the rest of society, sometimes with harmful or deadly consequences.

Exercise 10D

A cultural movement called “Cargo Cults” offers anthropology students an opportunity to practice cultural relativism. Read Cargo Cults to better understand the worldview associated with this religion.

Then, see if you can answer the following question:

How are symbols used in the European culture referenced in the reading? How are these symbols repurposed in this New Religious Movement?

10.15 Cargo Cults

While not a major world religion, Cargo Cults are another wonderful example to include in our chapter on comparative religion. As a more modern movement, Cargo Cults reflect the migration of people and how competing cultural interpretations can exist alongside one another.

The word “cargo” has Latin origins and refers to items being loaded onto a ship. In our own culturally-specific context, we define the word “cargo” to mean, “the goods or merchandise conveyed in a ship, airplane, or vehicle.” In other words, “cargo” is anything that we import or export with the intention of buying and selling.

In one community of Papua New Guinea, the European word “cargo” has evolved to carry another layer of local meaning that reflects many issues attached to the colonial encounter; it combines the local beliefs with the culture of more-powerful outsiders. In this local language, the term “cargo” refers to “trade goods” or anything brought over to Papua New Guinea by the people coming into their region from abroad (Stein and Stein 2017, 237). In other words, they use the word “cargo” to refer to the myriad of things that outsiders ship into their region including: money, weapons, clothing, technology, religious paraphernalia, etc.

Before the era of colonialism, the people of this region approached relationships as reciprocal. By trading goods and services equally between people, social relationships were maintained. Before colonialism, striving to make a profit off of others was not an acceptable practice. Anthropologists refer to this as balanced reciprocity and these societies largely maintain social ties through equal exchanges of goods or services. In this society, a traditional trade route exists called The Kula Ring. Within the Kula Ring, the people equally share time with a collection of sacred items that rotate between different communities. No group keeps the sacred items and all are expected to continue trading the items forward.

With the arrival of European colonial governments and missionaries, the people of this region started to witness a high volume of cargo arriving on ships and, later, on planes (Stein 2017). The wealth disparity between the local people and arriving Europeans was glaring and caused some locals to start to interpret the wealth gap using their own, culturally-specific terms (Stein 2017). This is a fascinating case to examine because, although the subsequent religion – called Cargo Cults – is often perceived as superstitious and absurd to the Western mind, their interpretations are actually exceptionally astute and correct. If we can examine the issues at hand using their own, culturally-specific context, we can actually understand more about ourselves.

Members of the Cargo Cult religion believe that Europeans accumulated a high volume of manufactured goods through ritual. The local people of Papua New Guinea watched the colonial officers dress in elaborate European clothing that served no apparent function, march about the island in striking uniformity, conduct meetings in a prescribed manner, and participate in other practices that are specific to the European culture. For example, a necktie is a fashion item that otherwise serves no function which caused the local people to struggle to understand why a person would wear a necktie. In response to this cultural clash, the religious belief of Cargo Cults emerged and believed that, if the natives of Papua New Guinea started to engage in the same rituals practices as the Europeans, they would start to accumulate as much wealth and “cargo” as the Europeans had.

The religion evolved to explain the wealth disparity and to explain the bizarre behavior of the outsiders. The native people saw the European behaviors as supernatural rituals that allowed them to access cargo magically. As a result, followers of the Cargo Cult religion started to develop rituals that copied the European behaviors. They march in lines with wooden “guns” over their shoulders, they stand at attention and raise “flags” up flag poles. On another occasion, they would place bark that resembles bullets in a sacred room and take hallucinogens in order to make actual bullets appear. In other words, they take these symbolic, culturally-specific practices and re-enact them within a different cultural context.

Another example focuses on fashion. Cargo Cult members design and wear their own form of necktie and understand neckties to be powerful amulets that allow access to cargo, wealth, and technology. We can practice cultural relativism and explore the mundane imponderabilia to understand how this makes sense. In their culture, only people wearing neckties had access to cargo and the European colonizers were actively seeking to convert the native people into a European way of life. So, the native people would give in to the European’s pressure to act more European and would start to dress like them.

Consider this: In our culture, a necktie symbolizes professionalism (among other things). This symbol is traditionally reserved for one gender (although more genders are increasingly wearing neckties, too). If a person who we expect to wear a tie failed to wear a tie to a job interview, then we likely wouldn’t think that person was fit for the job they interviewed for. As a result, that person wouldn’t gain the income of the new job and wouldn’t have access to wealth or to the technology and items that they hoped to purchase. Members of the Cargo Cult are not wrong in connecting European rituals – such as wearing a tie – to success. This is because the European culture has dominated wealth and global culture since the beginning of colonialism.

This new religion developed a new myth (please note: in anthropology we define a “myth” as “a sacred story that shapes a people’s worldview”. We don’t use this term in the dismissive manner that it’s used in common language). The sacred myth of Cargo Cults taught the people that their ancestors resided in another realm and that wealth, prosperity, and cargo could only be acquired from that realm through supernatural means (usually involving pleasing the ancestors). In their view, their ancestors intended for the people of the island to have the technology and goods (which were stored in the Land of the Dead) but, in their view, the Europeans stole the goods from the natives. In the Cargo Cults tradition, practicing magic will return the technology, wealth, and goods to the native people.

Remember that the European colonizers exploited native resources and people in order to amass their own wealth. The colonial governments did, indeed, steal natural resources and exploit native labor in order to profit, advance technology, and amass goods. In a real sense, the wealthy were stealing from the Cargo Cult followers and the colonial governments and missionaries were supposedly offering access to the wealth if the local people could become a part of European expansion.

Furthermore, a reason this interpretation emerged was due to the European’s cultural preference for what anthropologists call negative reciprocity. “Negative reciprocity” occurs when parties seek to gain more than they give. If, for example, the shirt you are wearing was made in a factory for $1 but you paid $25 at the store, then the company selling the shirt made more than they gave to you (this is considered negative reciprocity). While living near the people of Papua New Guinea, the Europeans asked for labor, land, and resources but never offered cargo to the native people (Stein 237-238). Anthropologist Shirley Lindenbaum writes,

“From [their] point of view…they had provided whites with territory, food, and services, and they expected a reciprocal endowment of valuables…In return they expected knowledge they could use to induce the gods to favor them as they had favored the whites.” (Lindenbaum 2013, 111).

The missionaries worked to convert the native people to Christianity during this same time. In the Christian worldview, prosperity is a sign of divine favor (Weber 2001). So, in the Christian worldview, the natives of Papua New Guinea would, in fact, be favored with economic development if they converted to Christianity. So, as a result, much of the Cargo Cult religion evolved to include Christianity. Rebecca and Phillip Stein’s book on the matter explains, “Much of the interest in the newly introduced Christianity was an interest in discovering the ritual secrets that the missionaries used to bring the cargo over from over the sea from the Land of the Dead.”

Wikipedia’s somewhat problematic explanation defines Cargo Cults as, “A belief system in a relatively undeveloped society in which adherents practice superstitious (magical) rituals hoping to bring modern goods supplied by a more technologically advanced society.” This common misunderstanding of Cargo Cults is simply not sufficient and requires a more advanced anthropological analysis. Anthropologists define “magic” as “any practice that is intended to change the fate of the people, usually through supernatural means” (Kuper 79). In this way, both the Europeans and native islanders were engaging in symbolic superstitious rituals (marches, meetings, flag raisings) in order to change their fates, and both believed that Christianity would lead to prosperity. Each unveils some truth about the other.

By examining the beliefs and rituals of the followers of Cargo Cults, we are presented with an opportunity to examine ourselves. Their etic perspective on our culture highlights what is socially-constructed, culturally-specific, symbolic, and superstitious. When these people interpret our cultural practices, they are doing the work of anthropologists and developing an understanding of our practices that makes sense in their own context.

10.16 Comparing and Contrasting Religious Influences

Let’s wrap up by comparing and contrasting the beliefs of the religions that we have discussed in this chapter.

Jesus and Buddha’s stories emerged within 500 years of each other, and their similarities reveal a great deal about what societies needed at the time. You may recall that the hero archetype is a common story-telling structure that exists across cultures and, of course, the stories of Jesus and Buddha follow that structure as well.

- Their philosophies and stories are very similar; for example, when Jesus gives the “Sermon on the Mount”, the first thing that he teaches is the “Golden Rule”. The Golden Rule says, “do not do anything to others that you would not want others to do to you”. On the other hand, Buddha gives his first lessons beneath the Bodhi tree and his first lesson is: treat others as you would like to be treated.

- Both Buddhism and Christianity preached nonviolence while living in violent societies, and it was a radical idea at the time.

- Both Buddhism and Christianity rejected material wealth and undermined the ruling powers of their society.

- Both Buddha and Jesus are believed to have had prostitutes as friends which reveals a common cultural oppression of women and a revolutionary new idea to overcome oppressive class structures.

- Both religious figures started their spiritual journey at age 30.

Jesus and Buddha’s origin stories are also quite similar:

- Jesus’ and Buddha’s legends are similar, as both of their mothers’ pregnancies were announced by angels: an elephant in Buddhism and Angel Gabriel in Christianity.

- Both mothers gave birth during a journey, with Mary traveling to Jerusalem, and Buddha’s mother returning to her hometown.

While the stories of Jesus and Buddha are generally quite similar, they end in very different ways. Consider each:

- It’s believed that Jesus was crucified by at age 32.

- It’s believed that Buddha died at age 90 from food poisoning. In the story, one of Buddha’s followers accidentally undercooked a fish and served it to him. Rather than dying dramatically, it’s believed that Buddha calmly explained to his distraught followers the lesson: everything eventually dies.

Of course, because Buddhism and Hinduism emerged from the same origins, both religions believe in reincarnation, karma, and samsara, both seek liberation from suffering through inward reflection and selfless service.

Zoroastrianism heavily influenced the development of the Abrahamic religions. Christianity embraces the originally-Zoroastrian idea of “good versus evil”, the idea that humans are engaged in a cosmic battle. Similarly, Zoroastrianism influenced the development of Hinduism as both religions share the ideas of spiritual responsibility (dharma).

Exercise 10E: Journal Reflection

How has your religious community been influenced by the practices and beliefs of other groups?

Exercise 10F: Study Guide

Define the following terms in your own words:

- The cross-cultural approach

- The evolutionary approach

- The diffusionist approach

- Personhood

- Mesopotamians

- Cuneiform

- Enuma Elish

- Polythsistic

- Monotheistic

- Ziggurats

- Reincarnation

- Samsara

- Karma

- Moksha

- Dharma

- Bhagavad Gita

- Akhenatan

- Aten

- Moses

- Zoroaster

- Dualistic

- Ascetic

- The Middle Way

- The Buddha

- The Four Noble Truths

- The Eightfold Path

- The Silk Road

- The Protestant Work Ethic

- Catholic

- Christian

- Protestant

- Protestant Reformation

- Prosperity Preachers

- Cult

- New Religious Movements

Briefly summarize the cultural contributions of the following figures:

- Akhenaten

- Prophet Zoroaster

- Siddhartha

- Jesus

- Moses

- Abraham

- The Prophet Mohammad

Chapter 10 Works Cited

- Ayoub, Mahmoud M. 2002. “The Islamic Tradition.” In World Religions: Western Traditions. edited by Willard G. Oxtoby. Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Boadt, Lawrence. 1984. Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction. New York: The Missionary Society of St. Paul the Apostle in the State of New York

- Cole, Joshua. Symes, Carol. Coffllin, Judith. Stacey, Robert. 2012. Western Civilizations Vol. 1. W. W. Norton and Company.

- Fagan, Brian. 2015. Did Akhenaten’s Monotheism Influence Moses? Biblical Archaeology Review 41:4 (July/August).

- Lambert, W. G. 2013. Babylonian Creation Myths Winona Lake. Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- Matthews, Warren. 2007. “Hinduism.” In World Religions. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Oxtoby, Willard G. 2002. “The Zoroastrian Tradition.” In World Religions: Western Traditions, edited by Willard G. Oxtoby. Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Sarma, Deepak. 2008. Hinduism: A Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Segal, Alan F. 2002. “The Jewish Tradition.” In World Religions: Western Traditions. edited by Willard G. Oxtoby. Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Stein, R.L. and Stein, P.L., 2017. The anthropology of religion, magic, and witchcraft. Routledge.

- Swancutt, Katherine. 2019. Animism. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology.

- Winthrop, R.H. 1991. Dictionary of Concepts in Cultural Anthropology. New York: Greenwood Press.

Chapter 10 Suggestions for further readings:

- Ehrman, Bart. 2014. “If Jesus Never Called Himself God, How Did He Become One?” Interview by Terry Gross. Fresh Air, NPR, April 7, 2014. Audio, 38. https://www.npr.org/2014/04/07/300246095/if-jesus-never-called-himself-god-how-did-he-become-one#:~:text=God.%20…-,During%20his%20lifetime%2C%20Jesus%20himself%20didn’t%20call%20himself%20God,all%20that%20he%20was%20God.&text=You%20do%20find%20Jesus%20calling,John%2C%20or%20the%20last%20Gospel.

- Henninger-Rener, Sashur. 2020. “Religion.” In Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition, edited by Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González. The American Anthropological Association. https://perspectives.pressbooks.com.

- Redford, Donald. 1987. The Monotheism of the Heretic Pharaoh. Biblical Archaeology Review 13:3 (May/June).

Written by Amanda Zunner-Keating, except for section 10.4 (“Animism”), which was written by Ben Shepard. Edited by Oscar Hernandez, Brian Pierson, Madlen Avetyan, and Tad Mcilwraith. Special thanks to student researchers/reviewers Phillip Te, Ethan Yu, Jared Montaug, and Ahmet Dikyurt. Thanks to Jennifer Campbell for curating photos; and to Melody Yeager-Struthers for organizing our resources. Textbook layout by Amanda Zunner-Keating and Madlen Avetyan. Audio recorded by Amanda Zunner-Keating.

NPR links on this are linked NPR’s website with permission from NPR. All NPR content (audio, text, photographs, graphics, videos) is protected by copyright in the U.S. and other countries. For more, visit NPR’s Rights and Permissions website.