11 Death and Dying

Chapter 11 audio sections 11.1-11.12 and 11.20-11.22 can be accessed on Soundcloud. Instructor resources for those sections are available on Canvas Commons. The audio for sections 11.13-11.19 can be accessed separately on Soundcloud. Instructor resources for those sections are available on Canvas Commons.

Chapter 11 Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Recognize and describe the impact of death in human societies.

- Summarize roles of death rituals across cultures.

- Describe the cultural meaning of cannibalistic practices across cultures.

11.1 Death from an Anthropological Perspective

Though it can be unpleasant to consider, death is a universal part of the human experience. Perhaps for this reason, cultural beliefs about the nature of death can have an important role in shaping our relationships, our ethical beliefs, and our very understanding of what it means to be human. This chapter explores the considerable variation that human cultures exhibit in the ways that we approach death, both in terms of how we understand its meaning, and also in terms of our behaviors and practices: what we do when a death occurs. To put it another way, this chapter does not so much aim to explore death as it aims to explore human life in light of death.

11.2 Holism in the Anthropological Study of Death

As we investigate variation in human cultures’ approaches to death and dying, we use a holistic perspective (see Chapter 1), showing how beliefs and practices concerning death connect to economic, political, and moral life in different cultural settings. Our view as anthropologists, in other words, is that it would be pointless to study funeral practices and beliefs about death without also understanding how they fit into the broader cultural systems in which they exist.

11.3 Cultural Relativism in the Anthropological Study of Death

Death is, in many ways, an observable phenomenon. In contrast, if anything happens to a person after they die, this is not as easy to observe directly. Interpreting what happens to us after death is a cultural task, and cultural views on the relationship between a “person” and that person’s body after they die vary widely. As we will see, even basic definitions of death – “What are its causes?” “In what ways does dying change a person?” “At what point can we even say that death has happened to someone?” – are not consistent from one culture to the next.

Some of the questions listed above might seem to have answers so obvious that just asking them reflects incredible ignorance on the part of the person expressing curiosity. However, part of our task as anthropologists involves stepping outside of our own cultural beliefs and expectations and recognizing that they – like all cultural beliefs and expectations – are just that: cultural. While all cultures provide members with some interpretation of death and dying, cultural relativism dictates that precisely how any given culture interprets these phenomena is appropriate for that group.

In this chapter, we will also encounter functionalist perspectives, which view different cultures’ ideas about death as adaptations that help groups to meet their culturally-specific needs. Meanwhile, Marxist perspectives will explore the ways that beliefs about death affect power relations and the distribution of wealth within societies of all kinds.

11.4 Death, Anxiety, and Religion

Among the anthropologists who study how people in different cultures grapple with the idea of death, some have gone so far as to suggest that our unease about dying may actually have led to the development of the first forms of religion. Religion, by this logic, is not simply a result of a human tendency to wonder about abstract themes like ‘the meaning of life’ or our ‘purpose.’ Instead, we can think of it as a sort of ‘tool’ that human cultures use to cope with a visible reality that has been part of human life in all places and at all times: the phenomenon of death and the anxieties and tough questions it raises for us.

Throughout his career during the early 20th century, Bronislaw Malinowski (1884–1942), a foundational figure in the history of anthropology (see Chapters 1 and 3), outlined an argument that death is one of the universal sources of anxiety for humans, and that religion is a universal human response to this anxiety. For Malinowski, to understand death as the result of unseen supernatural forces was also to portray its causes as comprehensible. When we think we can comprehend or even reason with the supernatural forces that affect the parts of our lives we cannot otherwise explain, we are able to rationalize seemingly unfair and tragic occurrences like death (Malinowski 1955).

In this way, Malinowski argued that belief in the supernatural had a function within human societies.It created (and still creates) a sense of order, an underlying logic in a world that might otherwise seem just a bit scarier, just a bit more random, and maybe just a bit more unfair (note that this is an example of what we have called functionalism in the anthropological study of religion. See Chapter 3).

Malinowski was not alone in his idea that human beliefs in the supernatural result from our fear of death. Sigmund Freud (1859–1939) – a towering figure in the development of the field of psychology – similarly suggested that an awareness of death has always disturbed the human imagination. To Freud, religious belief systems in their simplest form could have served as a means by which people comforted themselves in the face of death’s disturbing inevitability. Freud suggested that by creating concepts of the soul and the afterlife, ancient humans were able to convince themselves that they and their loved ones would not be truly gone after death. In this view, religion allowed ancient humans to comfort themselves with the knowledge that the dead would instead continue to exist, but in a different form, after they were physically gone (Freud 1930).

Exercise 11A

Anthropologists closely examine the death rituals that exist in each society. Mummification is a death ritual that was practiced in Ancient Egypt (and in other societies). Interestingly, humans were not the only ones mummified in Ancient Egypt. Listen to NPR’s story titled, “Archaeologists Discover Dozens Of Cat Mummies, 100 Cat Statues In Ancient Tomb.”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- Based on information from this report, how did people living in Ancient Egypt view their relationship with cats and beetles?

- How did Ancient Egyptians understand divinity? Please discuss both cats and gods/goddesses in your response.

11.5 Gawan Families in the Late 20th Century

In order to illustrate the role that supernatural beliefs can play in helping people to cope with anxiety and grief surrounding death, let’s briefly consider an example. During the 1970s, American anthropologist Nancy Munn conducted ethnographic fieldwork on Gawa, an island located in eastern Papua New Guinea that was inhabited by just over 500 people at the time (Munn 1986). Munn’s research focused on Gawan systems of exchange (their economy), but it also demonstrated the importance of a holistic approach since this topic could not be understood without exploring Gawan beliefs about death, the supernatural, and especially the family.

The Gawan concept of ‘family’ differed significantly from the one that Munn had learned about in her own cultural surroundings while growing up in New York. Gawans identified specifically with their mothers’ families, believing that this is where a person gets their balouma, or spirit. Gawans saw their fathers – as well as their fathers’ brothers, sisters, and parents – as ‘non-relatives.’ In a similar category to fathers, Gawans also viewed a person’s spouse and the family of that person’s spouse as being non-relatives: members of someone else’s family.

This is not to say that a person had no relationship with their father’s family or with their spouse’s family, however. In fact, despite their status as non-relatives, the families of a Gawan’s father and their spouse both held extremely important places in any Gawan person’s life. And as Munn showed, these non-relatives also had unique and very important roles to play in a Gawan’s person’s death.

11.6 The Gawan Mourning Process

When a person died on Gawa, Munn observed that the families of their father and their spouse were expected to fulfill very special responsibilities, despite their status as “non-relatives” of the deceased. The families of a dead person’s spouse and father would gather and mourn loudly and publicly for up to a week before a funeral would eventually be held, all while wearing special clothes. These clothes tended to deteriorate during the mourning process, which Gawans associated with aging, and also with death. Mourners also shaved their heads and colored their bodies black using charred coconut husks, again recalling the process of dying and decomposition in symbols all Gawans understood. They also spent considerable time in the presence of the deceased person’s body, making amulets out of his or her hair and nails. The mourners (again, specifically the families of the dead person’s father and their spouse) would later wear these amulets during the funeral (and sometimes for a long time afterwards). Through these rituals, the families of the spouse and the father of a dead person actually came to represent that person during a funeral (Munn 1986, 164-171).

After a deceased person’s burial was complete, the dead person’s family collected valuable, elaborate, and rare objects that represented the relationships, successes, and deeds of their loved one, and then gave these objects away to the various “non-relatives” who had served as mourners during the funeral. Munn suggested that this act of gift-giving allowed Gawans to process their memories of their dead relative. Interacting with the mourners, who were symbolically performing the role of the deceased person, made it possible for family members to feel less alone. For Gawans, a deceased loved one could even be said to ‘live on’ in the objects that represented their deeds, and also in the people who were part of their life and who were honored in the gift-giving ritual (Munn 1986:170). In this sense, Munn argued that Gawan practices surrounding death and the symbolism involved in those practices both helped Gawan people to process the emotional weight of a loved one’s death by giving them a chance to continue to interact with the deceased person symbolically.

11.7 Death Creates a Social Dilemma

Now that we have considered how cultural beliefs and rituals surrounding death can affect how individuals process grief, let’s consider these themes at a broader scale. You have probably heard the term “social network” used to describe online social media platforms, but this term actually describes something much more fundamental to human lifeways – something that has existed since the birth of our species.

At its core, “social network” refers to a group of individuals who are connected to one another – some directly and some only indirectly – through interpersonal relationships. Most humans participate in social networks that connect us to people outside our immediate families, and that extend beyond the small groups we see on a day-to-day basis. Most of us also participate in social networks that put us into indirect contact with individuals we will never actually meet in person. Although the precise scope of social networks in human societies varies considerably, extended networks have likely always existed in some form or another. They have likely existed in societies of all sorts, even those we might at first glance imagine to be fairly “isolated.”

For example, although they spent most of the year living in small family groups that ranged in size from only six to about forty people, prehistoric and early historic Iñupiat inhabitants of northwest Alaska built social networks that connected them indirectly to people thousands of miles away. To do so, they conducted ritual events, including those known as “trade fairs.” People from all over northwest Alaska – and in some cases from more distant areas as well – came together at these events, where they made new friends, learned valuable information about neighboring groups, and even sought out potential husbands or wives (Burch 2005).

Attendees often left Alaskan trade fairs with new contacts or having rekindled relationships with old friends from neighboring areas. Contacts and friends in neighboring areas each had their own set of relationships with others living in areas near them, and could extend their networks by attending local ritual events and trade fairs elsewhere. As a result, even though an individual Iñupiat person might not directly get to know people all over the Northwest Coast of North America, social networks connected them indirectly.

11.8 Funerals, Mourning, and Connections

As it turns out, funeral rituals can play a particularly important role in creating and maintaining social connections too. In many societies, when a person dies, their extended social network often hangs in the balance, since the chain of relationships that make up that network is now broken. In this sense, death is not onlya source of stress and grief for us as individuals (discussed above). By threatening to unravel or dismantle existing social networks, death also affects relationships among the living. In many societies, funerals present an opportunity for people to repair or reinforce social networks, counteracting the “break in the chain of relationships” someone’s death can cause.

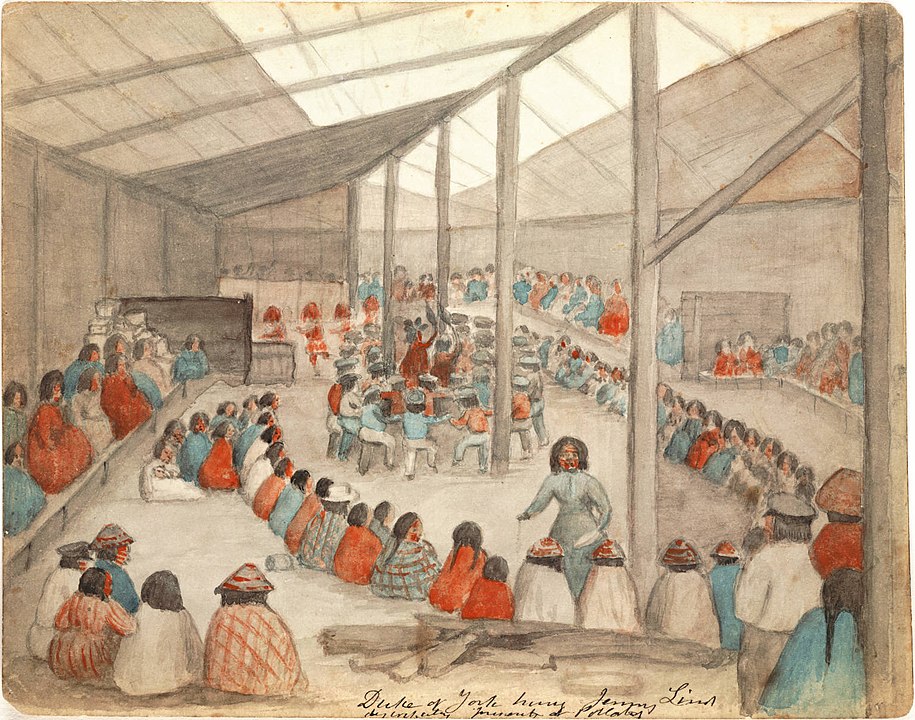

For example, 19th century Tlingit people in Alaska and the Canadian Northwest Coast provide an example of this “function” for funeral rituals. these groups conducted an elaborate series of funeral rituals, the final stage of which was called a ‘memorial potlatch.’ A deceased person’s distant relatives – and the extended families of those relatives as well – attended memorial potlatches and all attendees participated in a symbolic “renewal” of the relationships that existed between the family of the dead person and the funeral’s attendees (Kan 1989, 41-44). Out-of-town guests at these funerals included non-Tlingit people who came from considerable distances, particularly when wealthy or influential people died.

Like the Gawan funerals discussed above, the immediate family of a deceased Tlingit person – the hosts of the memorial potlatch – presented valuable gifts to most of the people in attendance, and in doing so, they recreated the relationships that had existed between the deceased person and the event’s guests, actually taking on the role that their deceased relative had played in these relationships. While Nancy Munn’s work on Gawa focused more on the way that Gawan gifts for mourners helped people to grieve, anthropologist Sergei Kan’s examination of historic Tlingit potlatches emphasized the ways that these events helped to maintain existing social networks in the face of loss and death.

11.9 Death Opens up Political Opportunities

Death also leaves a unique opportunity for ambitious people to pursue wealth and social status, and funerals often serve as the place where this pursuit is most visible. To illustrate this point, it will be useful to think holistically about the connection between religious beliefs, ritual activities, economics, and power in society.

Because rituals tend to bring together large groups of people, they present a unique kind of “stage” that a person can use to “show off” for a large audience, as discussed in Chapter 6. This is no less true of funerals.

Funeral rituals are often expensive in terms of the resources they require, particularly as they often involve large feasts (Hayden 2009). In many societies, getting ahold of enough of the right kind of food to conduct a funeral feast is not as simple as visiting a grocery store, and for this reason, hosting a sufficiently impressive funeral ritual can be challenging. A good host needs strong managerial skills, a network of people who can contribute food, and considerable resources of their own in order to finance the event.

To return to the example of the 19th century Tlingit memorial potlatch discussed above, attendees judged these events by their extravagance; hosts fed guests with huge quantities of meat, fish, and berries, and offered gifts of valuable animal skins (Kan 1989, 232). In fact, hosts tried to show off the wealth of their families by presenting so many skins and so much food that the skins were impossible to transport home and the food caused guests to vomit from overeating. According to Kan’s informants, if nobody vomited, at a funeral potlatch, it spoke badly about the food and reduced the hosts’ prestige (Kan 1989, 233).

Similarly, at funerals in the Trobriand Islands, valuable offerings were buried with the dead (particularly for chiefs and other important people), and hosts distributed yams to the events’ guests. Gathering and distributing yams was not simply a matter of feeding funeral attendees, it was also a way that hosts showed off the strength, cohesion, and organization of their family (Weiner 1987, 46).

In this sense, an impressive funeral feast is more than just a way of renewing the deceased person’s social network or grieving their loss. Throwing a successful feast is also a way for hosts to impress guests, to attract followers who can provide future political support, and to gain social standing.

11.10 Funerals and Wealth: Secondary Burials in Berawan Culture

While beliefs and practices surrounding death are connected to economic and political organization in many human societies, the precise nature of how funerals are conducted differs significantly. Ethnographic research that anthropologist Peter Metcalf conducted during the 1970s among the Berawan people in northern Borneo (an island in Indonesia) provides a particularly interesting example.

The Berawan of the 1970s were a group of roughly 1600 people living in four separate communities. Funerals were the largest and most costly rituals in Berawan culture, requiring enormous amounts of money, labor, and rice so that a host could throw a suitably impressive ceremony, hire entertainment, and construct a structure where the deceased person’s body would ultimately be buried. Berawan people viewed these parts of a funeral as ways to honor the wishes of a dead person’s spirit, and in part for this reason, funerals were critically important to them (Metcalf 1981).

One part of Berawan cultural practices that Metcalf studied intensively was a type of funeral ritual called a “secondary burial.” Secondary burial refers to the practice of disposing of the dead by conducting multiple funeral events so that a person’s body is moved or buried more than once. The Berawan would first hold a relatively small funeral immediately after a person’s death. They would later hold a much larger reburial event, and it was only then that a person’s remains would be deposited in their permanent burial place. These later reburial events sometimes occurred several years after a person died, and often after the body had been treated, processed, or changed in some intentional way.

Secondary burial practices had become less and less common in Berawan culture during the 20th century, and it was widely believed that they were disappearing due to globalization and contact with other cultures. Metcalf would examine the practice in considerable detail before eventually drawing a very different conclusion. Namely, he argued that – given the way the Berawan used funerals to display their wealth – there might be political and economic functions to these rituals (and political or economic explanations for their decline).

By demonstrating that they possessed the ability and the resources to host a truly gigantic ritual feast, Berawan funeral hosts could present themselves to guests as powerful and wealthy, thereby gaining public recognition and future political support. At the same time, conducting a funeral was expensive and time-consuming. By conducting secondary burials, ambitious Berawan individuals were able to save up resources to pay for a ritual event, and also to ‘spread out’ the work of amassing those resources and orchestrating the labor of political followers over a much longer, and therefore more manageable, period of time.

Cultures all over the world conduct burial practices that fit this “secondary burial” pattern, and during the 1970s, when Metcalf conducted his fieldwork, generations of anthropologists had examined them to glimpse the worldviews of the cultures who conducted them. Metcalf, however, observed that funerals were more than mere representations of Berawan beliefs (in this case, of ideas about the soul and the afterlife). Instead, he approached secondary burial rituals as a way Berawan people actively affected social life within their society. People used secondary burial practices to gain political opportunities that would not have been available if they needed to conduct funerals immediately upon the death of a loved one.

Why then were secondary burials disappearing if they were so important for Berawan people to gain recognition, prestige, and political support? Once, it had been necessary for most Berawan people to delay a funeral if they wished to make it sufficiently impressive. However, with the arrival of a credit-based economy in 20th century Borneo, Berawan families could now take out bank loans, and the need to conduct secondary burial rituals was reduced.

11.11 Death Raises “Legal” Issues

Dealing with a person’s stuff might not seem like a religious issue, and the term “legal” might also sound out of place in a chapter on religious approaches to death and dying. In most cultures, people do, however, have expectations about what a dead person is “owed” or what they “want” from the living. Social expectations about the needs of the dead and the debts they are owed can be said to function as laws in the sense that they serve as rules concerning property and ownership. These expectations often govern “inheritance” practices, dictating what the living can take from the dead, who can take it, and what the dead must keep if they are to remain on good terms with the living. Below, let us consider the outsized effect that religion’s “legal” role can play in determining how power is distributed within a society.

Human societies vary considerably in terms of power dynamics. Some societies – many, if you only consider contemporary societies – feature enormous differences between people in terms of wealth, power, and social status. Yet throughout the human past and present, many human societies have instead exhibited what anthropologists refer to as “egalitarian” social organization. In these societies, most adults possess relatively similar social standing within the group; there are no all-powerful emperors, no Silicon Valley tech billionaires, no subjugated masses, and no slaves.

Cultural outsiders often mistakenly interpret these groups as less advanced, lacking the technologies and social institutions that would allow for the accumulation of wealth and the consolidation of power. As it turns out, this view is largely incorrect, and reflects a deeply ethnocentric bias. We may think, “because social inequality exists in my culture, it must reflect ‘progress’ or a more evolved form of social organization.” In fact, egalitarian societies feature elaborate and highly evolved practices that serve as obstacles or “checks” against anyone interested in hoarding wealth or power.

For example, a variety of practices existed in historic and late prehistoric cultures of California that reinforced the relatively equal footing of all group members. When a particularly wealthy Wintu person died, their possessions were burned or buried, which left little or no physical property for offspring to inherit (Chase-Dunn and Hall, 127). Ohlone people of the southern San Francisco Bay area also destroyed or buried a deceased person’s property. According to their beliefs, failure to respect the dead in this way would make a person’s ghost enraged and cause it to enact severe punishments on the living (Margolin 1978, 56). Practices like these, which limit the transmission of wealth from one generation to the next, have been observed in many societies that also feature egalitarian tendencies.

Compare these practices to the ones you are familiar with in your own cultural surroundings that pertain to the transmission of wealth at death. In the United States, for example, the estate tax – a tax on money and other property that is inherited when someone dies – has long been a topic of considerable debate. Proponents of the estate tax argue that it helps to prevent the development of further social inequalities between the wealthy and the rest of American society – precisely the same function as the ritual practices that exist in egalitarian societies, discussed above.

None of this is meant to suggest that the estate tax should necessarily be seen as a “religious” custom, although many have made arguments for or against its implementation on the basis of the will of a supernatural being, a ‘God-given right,’ or a shared value that is greater than the needs of individual American citizens. What is noteworthy here is that religious practices surrounding death and burial serve the same functions or address the same social issues in many societies that legal institutions do in others.

11.12 Death in the Contemporary United States is Just as Strange as Anywhere Else

As we have repeatedly seen in this text, it can be easy to take your own cultural perspectives for granted – to believe that they are not actually “perspectives” at all, but objective truths. For many Americans, widespread practices surrounding death in this country are quite unremarkable; they seem to be based on science, and are unaffected by superstition. However, a brief examination of the ways that modern American (and English) burial customs have changed over several hundred years illuminates strange, irrational, and easily-taken-for-granted elements (Fowler 2004, 82-84).

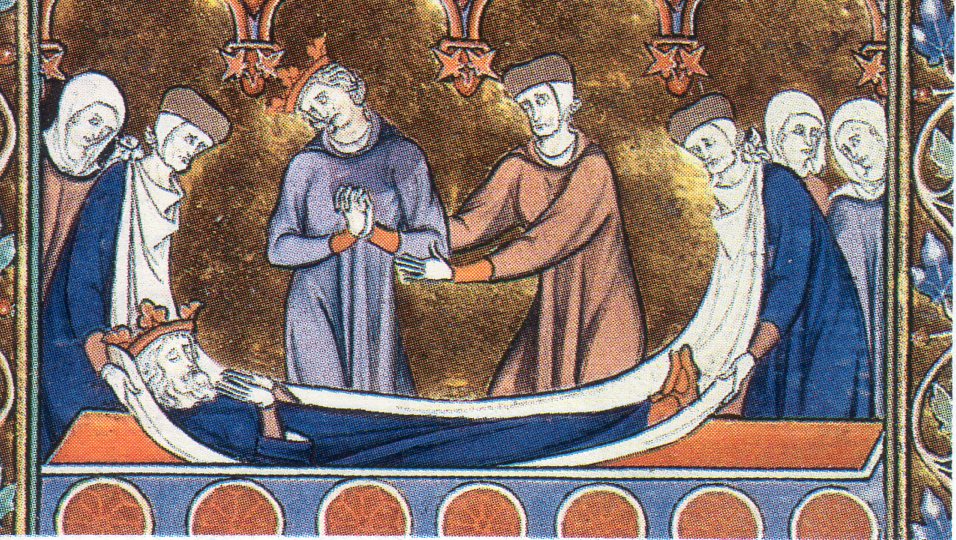

Archaeologist Chris Fowler suggests that during the medieval period (roughly 1000 – 1500 AD), many cultures throughout Europe associated death with bodily decay, and explicitly displayed the process of decay in symbols on tombstones and in other works of art. Decay and decomposition was not viewed as an unsightly or grotesque problem to be solved in this cultural context. Instead, it was a part of what was seen as the “normal” or “ideal” way that death and its aftermath should proceed. Death was generally depicted in texts and artworks as a slow process, and following death, the supernatural component of a person (a spirit or soul) was believed to travel to the afterlife gradually, paralleling the gradual process of natural decay.

In contrast, Fowler describes what he sees as a 20th century obsession in some cultures of Britain and America with a need to control or even to prevent the process of decay, in the bodies of both the dead and even the living (see the case study on the Nacirema in Chapter 6 for related discussion). Fowler lists a variety of ritual practices relating to death that reinforce these values or obsessions in Britain and America. When an individual dies, he notes that specialists usually establish a specific “time of death,” which frames death as an instantaneous event rather than a prolonged process. After this, the body rarely remains with their surviving family members for long, as it does in other cultural settings. Instead, specialists (coroners and morticians) manipulate the body in private, using chemical and surgical techniques, in an attempt to make the deceased appear as healthy, youthful, clean, and as peaceful as possible (rather than leaving it unaltered).

When the living family encounter the body of their loved one again, they usually wish to see it “in one piece,” and treat it as if it remains unaltered, despite the fact that morticians have removed any organs to be donated and have replaced or modified parts of the body during the highly invasive embalming process. According to Peter Metcalf, when he described embalming practices to his Berawan informants, they were disgusted and confused by the strange behaviors of Americans:

“I became aware that a sudden silence had fallen over my audience. They asked a number of hesitant questions just to be sure that they had understood me correctly and drew away from me in disgust when they found that they had. So shocked were they that I had to backtrack rapidly and change my story. The topic was never broached again. (Metcalf 1978:7).”

Clearly, to the Berawan, American funeral practices are not unremarkable. In fact, they reflect specific cultural views and expectations about death and the body; views that have the potential to utterly disgust cultural outsiders with different worldviews!

While burial and cremation, the two most common ritual burial practices in the United States and Britain, differ in several key ways, both achieve the same effect: removing the body from visibility so that the living can continue to remember the deceased as “intact,” well-groomed, and untouched by any hint of natural decay. In contrast, for the Berawan people, decay and decomposition are seen as necessary parts of the process of dying; to prevent these processes from occurring is to fail in one’s moral obligations to the dead and to one’s family. This is because the visible decomposition of the body mirrors the invisible transformation of the person’s soul. The soul separates from a person’s body at death, but it lingers nearby, stuck in a liminal state as the body decomposes. As that decomposition occurs, the soul transforms into a spirit (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of the concept of “liminality”).

This liminal period of decomposition is also dangerous for the living, since evil spirits can reanimate a body and cause harm to the living until that body is fully decomposed. No wonder the Berawan were so horrified by Metcalf’s description of American funerary practices. From a Berawan perspective, they trap the soul in a prolonged state of misery and expose survivors to considerable danger!

Exercise 11B

How have American burial practices changed over time? How have they remained the same? Listen to NPR’s story, “Bones In Church Ruins Likely The Remains Of Early Jamestown’s Elite.”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- In addition to serving the living, what role did early colonial churches play for the dead?

- How was the class system reinforced both in life and in death for early American colonists?

11.13 Mourning, Cannibalism, and Kuru

Remember that the principle of cultural relativism is central to this course (see Chapter 1). Cultural relativism is the principle that we cannot judge or understand another culture’s beliefs or practices based on our own, culturally specific logic. Rather, we must examine other cultures based on their culturally specific logic and understanding of the world. While this isn’t always easy, close, holistic research can lead us to new ways of understanding those who appear to be different from us. Let’s practice this skill with the example of cannibalism.

In 1961, a team of anthropologists traveled to a remote region of Papua New Guinea to investigate the cause of a fatal disease called kuru (Lindenbaum 2015). They were able to connect the illness to the practice of cannibalism, but was cannibalism the cause of kuru? The answer is no. Eating human flesh does not cause disease. Eating diseased flesh does, however.

Kuru spread among the Fore (pronounced “for-ay”) when a member of the community ate the diseased flesh of another member of the community. This disease functions similarly to Mad Cow Disease. Eating cow meat doesn’t automatically give you Mad Cow Disease, but eating the flesh of a cow who had Mad Cow Disease would then also give you the disease. What causes kuru is infectious prions (abnormally-shaped microscopic proteins) found in the brains of infected people. These proteins can infect other proteins they come into contact with, causing damage to the brain and nervous system, and even death. It is therefore those who ate the brains of the dead (usually women and children) who were then debilitated by this neurological disease (Lindenbaum 2015, 109).

Exercise 11C

The specific details of the Fore’s form of cannibalism are essential for anthropologists to understand. Read the article titled, “Mortuary rites of the South Fore and kuru” and take note on the worldview and ritual practices of the Fore.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- How do the Fore view the soul and the afterlife?

- Who performs the rituals necessary in this death ritual? Describe their responsibilities and consider how these duties correspond with their role in society.

11.14 Cannibalism as a Way of Managing Grief

We call the Fore endocannibalistic anthropophagers. This term refers to a community that eats their own dead (Stein and Stein 2017, 9). Please note that endocannibalistic anthropophagers do not kill people to eat and they do not eat the dead of other communities. They do not hunt down humans or farm humans for consumption. This type of cannibalism refers specifically to communities whose members only eat already dead members of their own community.

In another example, we may note that in some Jewish communities, the mourning period is considered to last for a full year, and individuals are expected to avoid certain activities during this time. For example, some Jewish people in mourning will not listen to or play music for the full year after a close family member has died.

The death rituals of our communities may be restricting, they may be empowering, or they may be both at the same time. Consider this example: one of the reasons why the Ebola outbreak of 2013-2016 in West Africa was so difficult to control was because some of the sacred mourning and death rituals in the region allow (or even require) mourners to touch, wash, dress, and cry over the bodies of their lost deceased loved ones (Manguvo and Mafuadze 2015). It is believed that connecting physically to a loved one’s body connects the living to ancestral spirits in the afterlife, and giving up this mourning practice would impact eternal life.

Unfortunately, Ebola is highly contagious immediately after a person has died; the virus is present in the bodily fluids of the corpse. It’s estimated that 60% of infected individuals contracted Ebola during a mourning ritual (ibid). People may resist public health directives that come from people they don’t know or trust (like government health officials), especially when those directives prohibit culturally required practices of mourning, including handling the bodies of loved ones who have passed away. It’s important for health officials to form relationships with local religious leaders in order to mitigate the impact that mourning rituals can have on people’s health. These leaders are in a position to modify cultural practices of mourning to the point that they are still meaningful, but no longer present a risk to the health of the mourners (ibid).

This West African mourning practice is empowering because it allows mourners special rights to express their grief. It is also restrictive because it has the potential to impact the mourners’ own health. As an anthropologist, it’s important to examine these issues through a variety of perspectives in order to understand the complete reality of the cultural practice and its implications.

Exercise 11D

The purpose, power, and value of land are often contested issues within a society. When a community utilizes land for burial, what obligations do other communities have to respect that? Listen to NPR story about burial sites in Arizona and this story about burial sites in Colorado to explore this type of conflict in modern, American society and reflect on the issues at hand.

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- What culture clashes are described in these stories? How do Native Americans and archeologists view the importance of this land and how does the American government view the importance of this land?

- What burial traditions are described? How and why are these sacred traditions?

11.15 Cultural Relativism and Fore Cannibalism

Because we live in a diverse society, we are accustomed to cultural conflict. This conflict usually arises when a group of people expects another group to conform to their own, culturally-specific practices. We can prepare ourselves to examine the plight of the Fore by first examining two popular forms of death ritual embraced by many societies and by asking ourselves why they are preferred in each context. Consider the following:

- Christianity is a diverse religion (like all others) and there is not one universal belief about the appropriate disposal of the dead in that community. But burial is commonly considered to be the best way to dispose of a dead body because, in many Christian communities, the body needs to remain intact in preparation for the Second Coming of Christ. Burying preserves the body and allows the body to be resurrected upon Jesus’ return (Choudry 2018).

- In Hinduism and Buddhism, it’s preferable to cremate a body because it’s believed that cremation allows the soul to be freed from the body (Choudry 2018). In this case, the soul may be reincarnated in a new life or it may be freed from the cycle of birth and death (called samsara) in order to reach liberation from suffering (called moksha).

Both communities are concerned with rebirth and with caring for the eternal soul of their loved ones. Christians want their souls to be reborn by their God upon his return, while Hindus and Buddhists want the soul to have a chance to be reborn in a new life. We can see that these two religions share a core value but that they seek to achieve it in mutually exclusive ways. Asking a Christian to cremate a body would prevent them from achieving salvation and asking a Hindu or Buddhist to bury a body would prevent them from achieving peace. We can practice cultural relativism to see that these cultural practices both make perfect sense in their own, culturally-specific contexts.

Remember that anthropologists take a holistic approach (defined in Chapter 1) when examining a cultural practice. If we don’t examine a community’s “big picture” worldview, we cannot make sense of their cultural practices and beliefs. As a student of anthropology, ask yourself, “what would need to be true for this cultural practice to make sense?” Then earnestly try to discover the answer whenever you encounter a cultural belief or practice that is different from what you expect or are comfortable within your own culture.

Remember that anthropologists practice objectivity, and therefore are:

- not interested in making moral judgments.

- not interested in creating a cultural hierarchy.

Anthropologists understand that moral judgments and cultural hierarchies are subjective concepts. It is not necessary for anthropologists to agree with or adopt a subjects’ mode of behavior or belief system, only to understand and appreciate it.

Cultural anthropologists know that what is “moral” is culturally-specific and that concepts like “better” or “worse” are also culturally-specific. We cannot judge another culture against our own ideas of morality, but we can strive to learn another culture’s idea of morality in order to understand them.

Let’s practice this with the Fore. The Fore believed that eating the body of their loved ones guarantees that the loved one’s soul will travel into the afterlife successfully while blessing the family who consumed their body (Whitfield et al. 2008, 3721). They believe that your body will, ultimately, be eaten by something (worms if you are buried and maggots if you’re not buried; Ibid 3722) and they believe that the best place that your body should ultimately rest is within the bodies of those who loved you. This process is called transumption, and the Fore believe that eating your family moves their soul into the afterlife (Ibid).

In the Fore worldview, your body becomes the fuel that sustains life for your children and then causes you to live on through them. But it’s not just one person who lives on in this way. As each generation has consumed their parents and grandparents, your body contains the entire ancestral line. To the Fore, burying a loved one in the ground would be a cruel fate that would separate the loved one, trap them forever in their dead body, and end the ancestral line.

At this point, you don’t need to morally agree with endocannibalism nor do you have to want to practice it yourself. But, as an anthropologist, you need to stretch your mind to be able to understand this unique cultural practice in its own terms. Soon, after you complete all of the work associated with this topic, you will get to decide how to analyze this cultural ritual using anthropological tools. We will closely examine the Fore’s form of endocannibalism and, at the end, you should develop your own ideas about this practice based on the evidence presented.

There is one final element to address: gender and power. As you read before, in the Fore community, the women and children were more likely to die from kuru because they are more likely to eat diseased flesh. While anthropologists do not like to judge another cultural practice against their own belief systems, we are interested in examining how these cultural practices are experienced differently by the groups with less power. As lower-status members of the community, women and children may not have the ability to protest the cultural practice of eating diseased flesh (this is hard to comment on without a direct study on the matter). According to Whitfield, Pako, Collinge, and Alpers, the women eat the diseased flesh as a sacrifice to the community and are later rewarded for doing this. According to Rebecca and Phillip Stein, women are given undesirable meat because they are less powerful in society. As always, please practice critical thinking and cultural relativism in order to develop your own ideas about this cultural practice.

Exercise 11E

Anthropologist Shirley Lindenbaum was a principal researcher among the Fore and it was her ethnographic work that ultimately brought kuru to an end. Read her article titled, “An Annotated History of Kuru.”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- “Gender Blindness” is the practice of ignoring the contributions and/or lived experiences of one gender (usually women) in fieldwork. How did gender blindness lead to poor medical research in this case?

- What major revelation (previously dismissed by biologists) did Robert Glasse and Shirley Lindenbaum uncover and how did this change the debate surrounding kuru?

- What problem arose when the local Fore people did not receive clear and accurate information about the anthropologists’ intentions for research?

11.16 Cross-Cultural Concepts of Cannibalism: Understanding the continuity of spirit

For many readers of this text, the concept of cannibalism may be seen as aberrant and taboo. For Westerners, the idea of cannibalism conjures up frightening or upsetting images. However, when the consumption of human flesh is part of societal religious practices, what does it really entail and what does it mean? In order to better understand the diversity and meaning behind the practice of cannibalism, we can examine cases of cannibalism as a societal practice – that is a mode of consuming humans that is an accepted practice in society. These practices are seen in many cultures around the world and are associated with ritualistic and religious beliefs that are deeply embedded in society. Please note that, in this course, we are not examining the aberrant forms of cannibalism (i.e., criminal) in Western society.

For cannibalism to be an accepted societal practice, the culture practicing the religion believes that partaking of the body or parts of the deceased ensures that the deceased person’s spirit lives on through them. For ritual cannibalism to be accepted, there has to be:

- A belief in a supernatural human spirit.

- A belief that the spirit can live on after death.

- A cultural acceptance of the cyclical nature of life.

11.17 Cannibalism in Catholicism/Christianity

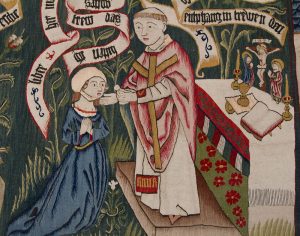

In the New Testament of the Bible, the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke detail what is known as the “Last Supper” of Jesus Christ, which occurs during the Jewish celebration of Passover, before Jesus is sentenced to death and crucified.

During this shared meal, Christ makes various ritualistic gestures as he breaks bread and shares wine with his followers. Specifically, in this story, he states the following as he passes bread to his followers, “Take, eat, this is my body.” Later in the meal Christ takes a cup of wine, and gives it to those present, saying “Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.”

This practice is commemorated today in Christian services around the world. In Catholic traditions, this is known as the Eucharist. This ritual is not symbolic; it is actually literal in its beliefs. The Catholic doctrine of “Real Presence” established the belief that the bread and wine are actually Christ’s flesh and blood, that Christ is literally present in the Holy Eucharist, and the wine is transfigured into the blood of Christ as it is consumed. A full one-third of Catholic Christians worldwide have a firm belief in the Real Presence of the Eucharist.

So, here from an anthropological perspective, we see a few concepts unfolding.

- The firm belief in the practice of cannibalism.

- A person who sacrifices themselves to be consumed as the ultimate sacrifice.

- A belief that the consumption of the sacrificed person unifies the consumer spiritually with the sacrificed person, so that the sacrificed person’s spirit lives on.

11.18 Revenge Cannibalism

The Korowai Tribe of Papua New Guinea practice a type of revenge cannibalism. The Korowai have a strong traditional belief in sorcery, witchcraft, and the belief of curses and revenge. These beliefs permeate the society and act as a sort of social sanction.

Anthropologists use the phrase social sanction to refer to a cultural practice that utilizes positive or negative feedback from others in order to enforce a standard of “proper” behavior. When we deny people access to social life in response to their “bad” actions, we are utilizing social sanctions.

For the Korowai, the belief in magic and sorcery works as a social sanction because “abnormal” behavior can cause one to be accused of being engaged in sorcery. People strive to get along with their community members in order to avoid societal punishment. However, these fears become so heightened that tensions can run high until fights and acts of revenge occur.

The Korowai explain illness and death in their own, culturally-specific way. In fact, until the 1970s when British anthropologists visited them, the Korowai had no idea there were any other people that were unlike themselves. Illness was viewed with suspicion and was explained as the action of an evil sorcerer. Before dying, a victim may state that they had a vision and they know who the sorcerer is that put a curse on them. If a child is dying, a child or an adult relative might name their sorcerer.

After the death, male relatives of the deceased person filled with rage, fear, and sadness, will go and find the named sorcerer, make them stand in a clearing, shoot them with arrows and then cook and eat the sorcerer. The parts and bones of the sorcerer are dismembered and put on branches to warn other would-be sorcerers of retribution.

What religious beliefs would support this action? The Korowai strongly believe that the sorcerers are cannibals. The Korowai believe that illness and death in a loved one is the result of the sorcerer’s magic. The Korowai believe in a practice in which a shaman literally eats the soul of a person from a physical distance; they call this practice remote eating (this results in the death of the victim) (van Enk 1997).

The Korowai claim they do not want to eat sorcerers. The Korowai say that human meat tastes terrible and that ‘normal people should not eat each other’. However, in order to prevent the sorcerer from eating people, the Korowai must eat them in retribution. For more, watch “The Gentle Cannibals” from Oxford Humanities.

Exercise 11F: Journal Reflection

Now that you more intimately understand cannibalism, has your opinion changed on the matter? In what way? What cultural representations of cannibalism are commonly

presented in your culture and how have these impacted your understanding of the practice?

11.19 Relics

In some religious traditions, dead bodies of holy people, parts of dead bodies, and objects associated with the body of a holy person, take on a particular significance. These bodies, body parts, and objects are called relics. We can think of relics as a material aspect of a sacred person or sacred event that has remained on earth. In this sense, certain religious traditions understand relics as blurring the boundaries between life and death; they bring death into the world of the living but may also be believed to assert the continuity of life in death.

Anthropologists Victor Turner and Edith Turner have noted that relics work through the principles of sympathetic and contagious magic (Turner and Turner 2011). Relics involve sympathetic magic, because they can be embedded in a reliquary that resembles the form of the holy person, such as an icon or statue. Also they are often a part of the body, or an object that has been in intimate contact with the body of the holy person. Such an object or fragment of the body is thought to carry as much sacredness as the person from whom it came.

Some scholars argue that the oldest example of relics are those of Pharaohs in ancient Egypt, whose mummified remains were interred in pyramids and venerated. Mummification began as a way to prevent decomposition of the physical body so that when the spiritual element of a person (“ba”) was reunited with the body in the afterlife the body would be complete and functioning. In this section, we will examine relics in two major religious traditions: Catholicism and Buddhism.