8 Religion and Syncretism

Written by Amanda Zunner-Keating, Madlen Avetyan, and Brian Pierson.

Chapter 8 audio can be accessed on Soundcloud. Instructor resources are available on Canvas Commons.

Chapter 8 Learning Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Define and describe examples of “syncretism,” “domination,” “acculturation” and “assimilation.”

- Explain the cultural, religious, and historical influences that fused together to create modern Voodoo.

- Explain the cultural, religious, and historical influences that fused together to create the modern Rastafarian movement.

- Explain the cultural, religious, and historical that fused together to create the Celtic cross.

8.1 Syncretism

When cultural trends and traditions spread or change, they do so within the context of particular power dynamics, and anthropologists strive to understand how these power dynamics impact the evolution, maintenance, or loss of cultural beliefs. Different groups of people bring their own cultural beliefs and practices into an inter-cultural interaction, and the culture of more powerful groups is usually the culture that survives the interaction. The negotiation of power and culture falls upon a spectrum of outcomes that anthropologists examine and, using four different terms to refer to different scenarios, we can more easily discuss how culture and power influence each other.

We use the term “syncretism” to refer to an occasion where more than one cultural force fuses together to create something new that still includes elements from the old cultural forces. Syncretism falls on the middle of the spectrum of power negotiation because both cultural forces maintain some power and cultural identity in the interaction. Then, moving out from each side of the spectrum, one of the groups will lose more and more ability to maintain their cultural identity in the face of the more powerful group’s influence.

We can look at Halloween as an example of syncretism. In the United States, people celebrate Halloween at the end of October because it is based loosely on the Christian holiday (All Saints Day/All Souls Day) that celebrates souls that have passed on to the afterlife. Many of the actual traditions come from various Pagan influences. And, at the same time, the holiday is largely defined by the American companies that seek to sell costumes, decorations, and candy.This holiday fuses together multiple cultural influences that then create something unique while still representing the diverse cultural forces that are at play.

On the far other end of the spectrum is “domination.” We use the term domination to refer to an occasion where one group’s culture is entirely wiped out in the face of a more powerful cultural group. For example, throughout the colonization of North America, the world witnessed rapid and complete loss of many Native American cultures that were systematically wiped out entirely. As a consequence of domination, some of Franz Boas’ and A.L. Kroeber’s work focused on the rapid collection of artifacts, language recordings, and notes about religious and cultural rituals of some of these Native American communities. Their hope was to preserve some knowledge of these people to survive their tragic elimination from the planet. This type of work is called “salvage anthropology” or “salvage ethnography.”

Some salvage anthropology was a success. Today, the handful of fluent Passamaquoddy-speakers of Maine are transcribing the recordings of their native language taken by anthropologist Walter Jesse Fewkes in 1890. The youngest living speaker of the language and Passamaquoddy community leader, Dwayne Tomah explained in a 2019 interview that they are using the recordings to, “be able to revitalize our language and bring it back to life again” (Feinberg 2019).

Along both directions of the spectrum, and with varying degrees of power struggles, are “acculturation” and “assimilation.” We use the term assimilation to refer to the event of a less powerful community being forced, through coercion, to entirely lose their cultural identity in the face of a more powerful cultural force. When people are pressured to assimilate, they are typically expected to lose their accent, their native language, their native religion, to cease celebrating their holidays entirely, etc. Although similar to domination, assimilation differs from domination because assimilated people do still exist (but they have undergone intense transformation). Dominated cultures are, tragically, completely lost. A concept that lies between syncretism and assimilation is acculturation. Whereas syncretism equally fuses together multiple influences so that each influence can be adapted to meet ever-changing cultural needs, acculturation reflects more of a power imbalance where the less powerful community quickly integrates the more powerful community’s cultural forms without a great deal of context. Research on acculturation typically focuses on the myriad of ways that non-European cultures were forced to quickly adopt European cultural traditions in the face of colonization. European-style dress, marriage traditions, and currency are examples of rapid cultural adoption faced by non-European peoples during early colonial processes.

The reason why we situate syncretism in the center of the spectrum and not on one end as an extreme is because all cultural exchanges happen in both directions, with both parties containing the potential to influence the other. As we move forward through our examination of the development of Haitian Voodoo, we will see examples of syncretism, acculturation, assimilation, and domination, so please keep these terms in mind.

Need help understanding these concepts? Read “Hypothetical Power Scenarios” for more clarification.

Exercise 8A

Salvage Anthropologists worked to collect cultural recordings and materials from communities that are disappearing from the planet. Listen to NPR’s, “Historic Recordings Revitalize Language For Passamaquoddy Tribal Members.” This story reflects an occasion where salvage anthropology assisted in the preservation of a Native American language.

Then see if you can answer the following questions:

- How many fluent speakers exist of the Passamaquoddy language? What does this tell you about the tribe’s colonial history?

- How are these recordings being used now?

8.2 A Close Examination of Syncretism: Haitian Voodoo

The following pages will work through the syncretism of multiple cultural factors that resulted in Haitian Voodoo as we know it today. To begin, we’ll discuss the history of Haiti to better understand the myriad of cultural influences and events that have shaped the nation’s identity. Then, we’ll discuss the main characteristics of Haitian Voodoo as it is practiced today to offer students an opportunity to apply anthropological tools.

To begin, let’s define “Voodoo.” The word “Voodoo” (or, “Voodoo”) means “spirit” and a vodouisant is a person who “serves the spirits” (Desmangles 1992). While predominantly practiced in Haiti, Voodoo is also commonly practiced in other parts of the world.

8.3 A Brief Background on Haiti

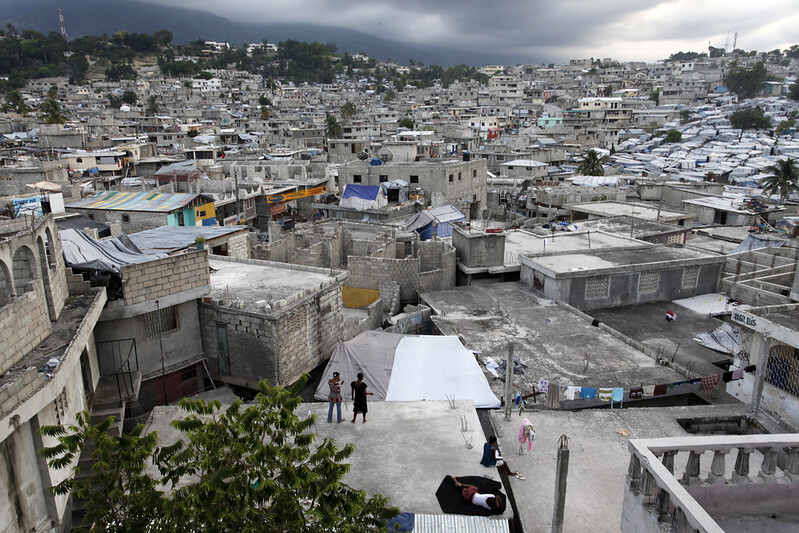

Haiti is a country in the Caribbean. You can reach Haiti in about 40 minutes after taking off in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Haiti is located on the Western half of the island of Hispaniola and is next to the Dominican Republic. Haiti’s history is incredibly fascinating, and the culture is rich with community strength, resilience, music, spirituality, and great dignity.

While there is much to know about Haiti, it is important to note that Haiti’s existence is the result of a slave rebellion. During the colonial era, Haiti was a highly profitable sugar cane producing colony that enslaved human beings in order to turn a high profit. In the face of extreme brutality, the enslaved people revolted, killed the slave owners, and directly established a country for themselves. This inspiring story is central to their national identity and to the evolution of the local culture.

Currently, Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas. As a result, many countries around the world are interested in becoming involved in Haiti’s affairs. The following will examine Haiti’s international relations, religious diversity, economic status, and colonial legacy in order to paint a complete picture of the meaning behind Haiti Voodoo. Through the examination of history and international power relations, we can better practice cultural relativism and we can achieve an intimate knowledge of a religion that is mystifying to the world at large.

8.4 History Shapes Culture

What comes to mind when you think of Voodoo? While we typically discourage our students from focusing on stereotypes, in this particular case, they are interesting and appropriate to examine. The word “Voodoo” conjures up images of skulls, blood, animal sacrifice, dark magic, and all of these are, actually, quite reasonable representations of the religion. It is true that Haitian Voodoo incorporates animal sacrifices, utilizes human skulls in some rituals, and – most importantly – it’s true that Haitian Voodoo is feared by most. As Haitian community leader, Willio Deseme, explains,

“Most people in Haiti fear Voodoo, but most Haitians believe in it. Most Haitians know that Voodoo is not something to mess around – it’s not a game and it’s dangerous.”

It admittedly sounds contradictory to state that Voodoo is central to Haitian culture while also being feared by the majority of people. While many people outside of Haiti fear Voodoo in a frightened or confused way, the Hatian people fear the power of Voodoo out of respect. As Willio further explains, “Haitian people know that in Voodoo there are two faces: a good and a bad. It depends on how you use it and which Spirit you invoke.”

It is actually quite easy for Americans to understand how Haitians perceive Voodoo because most Americans understand Voodoo in a similar fashion. Most Americans and most Haitians believe that Voodoo contains some kind of formidable power in which one should not trifle. If you ask the average American to participate in a Voodoo ritual, they will look at you in horror, and refuse (Haitian people express a similar horror, but it is based on your utter lack of understanding inherent in your request).

Consider the following example from Amanda Zunner-Keating,

“I spent my years in Haiti working with a dozen local organizations including a handful of orphanages. Most orphanages are religiously affiliated and three that I worked with were strictly Protestant. One, the most welcoming and generous, was both Protestant and Voodoo. Although this orphanage had the best facilities and supplies, the children from the three strictly Protestant orphanages refused to attend events at the orphanage that embraced both Protestantism and Voodoo. They were not prejudicial to the children or adults at the organization, but they were afraid to step foot on the premises for fear of engaging with spirits that they did not intend to engage with.”

The popular adage goes that “70% of Haitians are Protestant, 30% are Catholic, and 100% are Voodoo.” This is an important point to highlight. Haiti is a vehemently Christian country: buses and buildings have Bible quotes painted across them and many attend church multiple times each week. It’s not difficult to find two churches on each side of a street that compete with each other to hold the loudest – and earliest – church services each weekday. Haiti firmly loves the Bible and worships Christ; but most also believe that spirits surround their everyday lives. These two religions are not mutually exclusive because Voodoo arose from Christianity and each developed within the context of Haiti’s self-liberation from colonial powers.

Haiti’s history is an incredible story of resilience. The island has witnessed generations of brutality, genocide, and various abuses and yet the people continue to live on with strength and fervor. Haitian Voodoo contains fear,and some violence, not because the people are inherently fearful or violent but, rather, because they have endured and survived generations upon generations of both. This spirituality reflects the world that its adherents have survived.

Cultural anthropologists study religion without any interest in the “truth” or falsity behind the followers’ religious beliefs. Instead, we study religion because the endless diversity of ways that spiritual beliefs present themselves are an indicator of what the people’s lived experience is, and has been. Structures, traditions, and the moral fabric of our religions directly reflect who we are, and what we have gone through, as people. Haitian Voodoo does include violence and fear, and it does not include any guarantee of fairness or justice. Knowing this, we should not conclude that the hearts of this religion’s followers are, themselves, inherently more fearful or violent. But, rather, we must understand that the elements of this religion reflect the generations of brutality that people living on this island have experienced since the 1400’s.

8.5 What Happened to the Taino?

When we hear the words, “In 1492…” our brains quickly complete the phrase, “…Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” Please pause and remind yourself that Christopher Columbus never reached the shores of the United States. Why, then, is he integral to the US’s cultural identity?

Any student educated in the American school system can quickly name the three ships sailed by Columbus: the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa María. In 1492, on Christmas Eve, the Santa María crashed off of the Northern coast of the island that we now call Haiti (Girard 2010, 18). As Columbus and his men offloaded toward land, they were approached by the native Taíno people, who were wearing gold jewelry (Rouse 1992, 143). Columbus and his men were deeply interested in stealing gold for the Spanish Crown, and subsequently left a group of Spaniards on the island to establish a settlement (Ibid). Using the remains of the destroyed Santa María, the small group proceeded to build a settlement named Fort Navidad (in honor of the date of the crash). Columbus left the island with plans to return. At some point, the Taíno people became privy to the European’s intention to rob their lands of natural resources and promptly killed all of the Spanish settlers. They are described by Irving Rouse as, “adventurers who caused their own demise.”

Only moments into the history of the island, we are seeing an attempt to exploit and brutalize a native people and the native people’s violent resistance. This is the first event that shaped the tone of this island’s interaction with European and other global powers.

The Taíno were a native, Arawak people of the Caribbean who numbered around half-a-million (Girard 19). The Taíno called the island, “Hayiti” which is where we get the creole name “Ayiti” today. But, Columbus named the island “Hispaniola” in honor of the country which sponsored him. When Columbus and his men returned to the island, they enslaved the Taíno to mine the gold out of their land (Mintz 1985, 33). But the Taíno did not only face slavery, they faced brutality in all areas of their lives.

While colonialism was widely practiced by the majority of the European powers, each European country had their own particular style of colonizing native peoples. The French, for example, were particularly interested in turning their colonized subjects into “French” subjects by spreading their language, culture, and religion. The French colonial law afforded a few more dignities than some of the other colonial powers offered.

On the other hand, the British tended to view native peoples as objects to be utilized or to be overcome. Unlike the French who wanted to spread their culture, the British were known to focus on claiming land and resources to benefit the British crown.

The Spanish, however, were notoriously the most brutal in their colonization techniques. As “conquistadors” they sought to pillage the lands, rape, and eliminate the people in order to fully conquer the parts of the world that they were colonizing. This is why much of the Spanish-speaking world outside of Europe is genetically related to the Spanish in Spain. The Spanish brutalized the people they colonized, and this included the Taíno.

Historian Philippe Girard offers us two stories to illustrate how the Taíno suffered under Spanish colonization. He writes,

“Columbus and later Spanish colonists were not settlers in the traditional sense of the term. They did not intend to acquire land, build a log cabin, and become farmers. They were conquistadors: they were ambitious nobles and merchants who looked down on manual labor and dreamed of conquering a strange civilization, killing its leaders, enslaving its natives, and exploiting a quick windfall of gold and spices. Killing the Taíno leaders…they did: The tragic story of Anacaona Illustrates this well. Anacaona Was a Taíno Haitian princess whom the Spaniards asked to organize a big feast for Governor Nicholas Ovando. When she and the other [leaders] gathered for the festivities, Spanish soldiers set the meeting on fire and wiped out Hispaniola‘s leadership; Anacaona survived the fire, only to be put on trial and hanged. Taíno commoners were subsequently forced to work on gold mines and plantations.

Hatuey, another Taíno leader, was so revolted by the Spaniards mistreatment of his people that he fled Haiti for Cuba. Led by Diego Velazquez de Cuellar, the persistent Spaniards landed in Cuba to pursue him. And 1512, after years of guerrilla warfare, Hatuey was captured and sentenced to be burned alive. The Franciscan friar suggested that, should he repent and convert to Catholicism, his captors might show mercy and substitute garroting for the agony of death by fire. Plus, the Franciscan added, Hatuey would spend eternity in Heaven. When questioned by Hatuey if Spaniards also went to Paradise, the Franciscan responded that the best Spaniards did. “The best are good for nothing”, Hatuey snapped back, “And I will not go to where there is a chance of meeting one of them” (Girard 2010, 20).

Archeologist Irving Rouse points out that not only was Hatuey burned at the stake, but also his followers were burned (Rouse 1992, 156).

Nicholas Ovando, mentioned above, was notorious for his brutality on the island. In 1502, the Spanish unleashed an attack dog to kill a Taíno chief in the southwestern part of the island. The Taíno protested this killing and, in response, Ovando kidnapped seven hundred Taíno and knifed them to death in a hut. He then displayed their bodies publicly as a warning to other Taíno seeking freedom (Rouse 1992, 154).

While working to mine the gold out of their native land, the Taíno were physically brutalized and exposed to diseases (Mintz 2010; 138-139; Rouse 1992, 155). Any Taíno who resisted slavery was killed (Rouse 1992, 151). When the gold mines were not offering enough gold to please the Spanish king and queen, Columbus and his men kidnapped enough Taíno to fill an entire ship. They sold them into slavery for profit. Some Taíno were shipped directly to Spain to serve Spanish households where they died.

The rest of the population was killed, causing the Taíno people to be completely wiped out. No Taíno survived their encounter with the Spanish and we will never again be able to meet a member of this culture. This is an example of domination. While some people in the Caribbean do have partial Taíno heritage, the society – and specifically the traditions on the island of Haiti – was completely eliminated from the face of the earth as a result of colonization (Farmer 2012, 123-124; Girard 2010, 20). The Spanish even burned sacred items from the Taíno religion under the belief that it was a devil-worshipping religion, and very few Taíno artifacts have been found (Rouse 1992).

This was a successful genocide against the Taíno, and the Spanish subsequently drained the island of gold. Throughout the enslavement and killing of Taíno people, more and more Spanish families moved onto the island to continue their colonizing efforts.. Some of these Spanish families brought kidnapped and enslaved Black Africans with them to the island. The Spanish established a hierarchy of enslaved peoples where the Taíno were expected to work in the gold mines, but the Africans were expected to serve the Spanish families. The numbers of kidnapped and enslaved Africans rose rapidly: in 1540, the Taíno were outnumbered by the people brought to and enslaved on the island. In time, when all of the Taíno people were lost, and the island was fully mined of its gold, it was time for European colonial governments to establish a new endeavor on the island. It was around this time that sugar emerged as a popular item for consumption across Europe, and colonial powers sought new climates within which to establish sugar plantations. But, without any Taíno to force into unpaid labor, Europe looked to the African continent for human beings to force into slavery.

In 1697, Spain handed over the western half of the island to France who renamed it Saint-Domingue. During this time, sugar production was an incredibly valuable industry and the climates in the Caribbean and the American south were conducive to growing sugar. Haiti, as anthropologist Sidney Mintz explains, “was rapidly transformed into the most profitable colony in the history of the New World” (2010: 89). Again, when we examine colonial history, we must examine the process through which Europe was developed at the expense of the colonized lands and people. Through the process of eliminating an entire native people, stripping the island of its natural resources, then enslaving hundreds of thousands of people, France and Spain were able to amass wealth in the form of gold, sugar, and huge profits while the Taíno and enslaved West African communities were torn apart.

8.6 Outcomes From Slavery

There is some debate among historians about which slave-holding colony was the cruelest. As slavery, in all its forms, strives to dehumanize and brutalize human beings, it seems impossible to decide which form of slavery was the most horrible. For example: those who strove to own slaves in the United States were known to separate families and sell children; they even forced reproduction in order to profit more. This is an extremely cruel and brutal way to treat humans: particularly cruel and brutal to the women and children.

Whereas people who were enslaved in colonial Haiti typically did not survive long enough to have children at all (Girard 2010, 26). The violence upon their bodies, diseases in which they were exposed, and extremely difficult climate caused most to die in a short period. As anthropologist Wade Davis writes,

“Bloated by wealth unlike anything seen since the early days of the conquest, the colonial planter of [Haiti] made an institution of cruelty. Field hands caught eating cane were forced to wear tin muzzles while they worked. Runaways had their hamstrings sliced. Brandings, indiscriminate floggings, rape, and killings were a matter of course, and for the slightest infraction a man was hung from a nail driven through his ear (Davis 2008, 191)”.

It may be impossible to decide which form of slavery is crueler, but we do know that the two different manifestations of cruelty led to different cultural adaptations among the people who were captured, moved across the world, and enslaved in each location. Over time, the enslaved people living in the United States’ culture became more and more “Americanized” as new generations were born, forced into slavery, and each new generation was more familiar with American culture than the African cultures of their parents and grandparents.

In Haiti, because enslaved people died more quickly, the French replenished the population by capturing and bringing in more and more people from the African continent. France focused primarily on bringing over people from the West. Because people from West Africa were continuously arriving, the enslaved population in Haiti maintained a stronger connection to their African religion, language, and culture more than those living in the United States. Here is where we can start to track syncretism on the island. French law required that enslaved people be baptized and introduced to Christianity while, at the same time, more and more believers in Yoruban religion were arriving. These two cultural forces fused together – along with a few other cultural influences which we will soon discuss – to start to develop the Voodoo religion that we know today.

8.7 Enslaved Populations on The Island

Capturing and enslaving human beings to grow sugar in this region of the world was so profitable that the numbers of people forced into slavery grew rapidly. Historian Phillipe Girard writes, “In 1700, there were…9,000 slaves on [the island]. But, in 1790, at the height of the island’s prosperity, the colony imported 48,000 slaves that year alone, and the total slave population topped 500,000″ (Girard 2010, 24). To put this number into perspective, please pause and look up the population of the town where you live. Try to compare the amount of women, children, and men who were forced into brutal slavery during this time to the number of people in your own community.

While there were 500,000 enslaved people on the island, there were only 30,000 free whites. You may now be wondering, if the West African people on the island outnumbered the Europeans, why didn’t the enslaved people didn’t rebel against slavery? The answer is: they did. They successfully revolted against slavery. And, Voodoo was central to their liberation.

Over time, enslaved people on the island escaped from plantations and established free communities. Called “maroons”, they would retaliate against plantations in order to liberate other enslaved people and to get supplies (Davis 2008, 192; Girard 2010, 28). It was within these maroon communities that the origin story of modern Haiti took place.

8.8 The Syncretization of Voodoo

Remember, “syncretism” is defined as the event where 2 or more cultural forces fuse together to create a new cultural force that still retains elements of the original cultural influences. Haitian Voodoo is most commonly considered to be a fusion between Christianity and West African religion but, in reality, there were more religious influences at play during the development of Haitian Voodoo. Let’s examine each influence:

First, the people who were captured and enslaved on the island came, primarily, from West Africa. We call the religion “West African Spirit Worship”, which is a polytheistic religion (a belief in multiple divine beings) that believes in the power of nature. West African Spirit Worship holds an enchanted worldview that believes that divine spirits interact with humans and flow through the natural world.

The following facts are taken from Rebecca and Phillip Stein’s book on the anthropology of magic, witchcraft, and religion: West African Spirit Worship is a term that we use to refer to the religions of the Yoruba, Fon, and Ewe people who lives in the southwestern region of Nigeria and the Republic of Benin (Stein and Stein 2017). The Yoruba:

- Have an ancient culture

- Believe in two sets of divine beings: a major God who exists but is not involved in human affairs and the spirits who are reachable by humans called “orisha”

- The orisha are human like in form and in emotional range

- The orisha are not inherently good or evil, but are complex like humans

As stated earlier, French law required that enslaved people be baptized in the Catholic tradition, which caused them to be introduced to Christianity (Stein and Stein 232). So, we know that Christianity is central to the development of Haitian culture and religion. However, the priests who led the communities in the colony were not typically the leaders who had excelled in France. Rather, they were members of the clergy who, often, had an ethical or academic lapse in their training. Historian Philippe Girard calls them “renegade priests” and argues that they were a central force in the unique type of Christianity that was presented to enslaved people across the colonies (Girard 2010, 30 and 37).

During this time, West African people living in the French colony were forbidden from practicing the religion of their homeland. As West African Spirit Worship was forbidden, the enslaved people were able to combine the religion with Christianity in order to participate in both religions at the same time. For example,an individual could pray to a Catholic Saint in public and, in their hearts, intend for the prayer to be heard by a West African orisha. Please keep this example in your mind as we will return to it later.

During the time when sugar was rising in demand and France was becoming exceedingly rich, witchcraft, the occult, and sorcery were increasingly popular in Paris. We use the term occult to refer to any kind of mysterious and supernatural belief system or practice. Throughout human history and across cultures, we see occultism rising and falling in popularity in a cyclical manner whereby people are sometimes very interested in, for example, astrology, psychics, or tarot card readings. You only need to visit Urban Outfitters to see how trendy the occult is today, and, during Haiti’s colonization, the occult was similarly in vogue for the wealthy and powerful of Paris. Naturally, the less powerful colonial French people living in Haiti wanted to emulate the trends of Paris and, as a consequence, they engaged in occultism. They would, for example, perform a spell to ensure a good crop and, as you can imagine, they would require an enslaved person to assist in this magical ritual (Girard 2010, 30). When we examine Voodoo rituals, we can see the presence of magical rituals in the religion.

Before West African people were captured and transported across the globe to work for European colonies, communities were heavily influenced – and many converted to – Islam. In West Africa at the time, it was common to combine the Islamic traditions with West African Spirit Worship, and some leaders of the Haitian Revolution identified as Muslim throughout the revolution. Islam held a unique view toward racism and slavery at the time ;in his final speech, Islam’s Prophet Muhammad stated, “There is no superiority of an Arab over a non-Arab, or of a non-Arab over an Arab, and no superiority of a white person over a black person or of a black person over a white person, except on the basis of personal piety and righteousness (Afsaruddin 2020). Islamic tradition tells the story of “Bilal” a Black enslaved African who was freed by the prophet Muhammad’s friend Abu Bakr and then offered a position of prestige within the new Muslim community (Afsaruddin 2020). It’s reasonable to assume that such stories pushing for racial equality were well known to many toiling under a race-based system of slavery in the European colonies.

So, at this point, it’s important to understand that multiple spiritual beliefs were present in the colony: Christianity, West African Spirit Worship, Occultism, and Islam.

8.9 The Loas of Voodoo

Remember that religion reflects the lived experiences of a people; religion evolves to meet the specific needs of each community. Reflecting briefly on the violent and brutal nature of Haiti’s colonization, you can clearly understand how the religion has earned a bloody, mysterious, and powerful reputation. Voodoo was born as resistance to oppression and reflects the reality endured by its followers.

Let’s briefly pause the telling of Haiti’s history to look over the basic structure of Haitian Voodoo. Voodoo believes in a major god or “Bon Dieu” who is not particularly involved in human affairs (Girard 2010, 31). Rather, the followers direct their prayers to the loas (spelled “lwa” in Haitian Creole) who are divine spirits and are much more human-like and who are interested in human affairs. Loas often have very human tendencies: many like to curse, make dirty jokes, and may be alcoholics.

As mentioned earlier, under colonial rule, practitioners of Voodoo were not allowed to worship the Gods from West Africa and, rather, would combine their faith with Christianity. Over time, each West African Spirit was syncretized with a Catholic saint in the belief that they were one in the same (Stein and Stein 2017, 233-234). Here are some examples of loas in Voodoo and their corresponding Catholic saints:

- Papa Legba is believed to be the keeper of the underworld. He stands at the crossroads of this world and the next and must first be addressed before one can attempt any Voodoo ceremony (Stein and Stein 2017, 234). Papa Legba is believed to speak all of the world’s languages so that he can understand the prayers of all people. Papa Legba is associated with Saint Peter because, in Catholicism, Saint Peter is believed to stand at the gates of heaven.

- Ogun is believed to be a loa whose job it is to make the world a nice place for humans to live but that he is still working on this project. He is the loa of war, iron and metallurgy and, because he’s often depicted with a sword, he’s associated with Saint James.

- Damballah is a serpent loa who is believed to have created the Earth by using his coils to shape it and by shedding his skin to create rivers and oceans. Voodoo ceremonies are often performed around a pole that will have Damballah painted or carved onto it. Damballah is associated with Saint Patrick who is frequently drawn with snakes in Catholicism.

- Erzulie Danto is the spirit of fertility and motherhood. She’s specifically seen as the saint of single mothers, working mothers, and battered women (she’s usually shown as having a wound on her face). Erzulie Danto is associated with Mary.

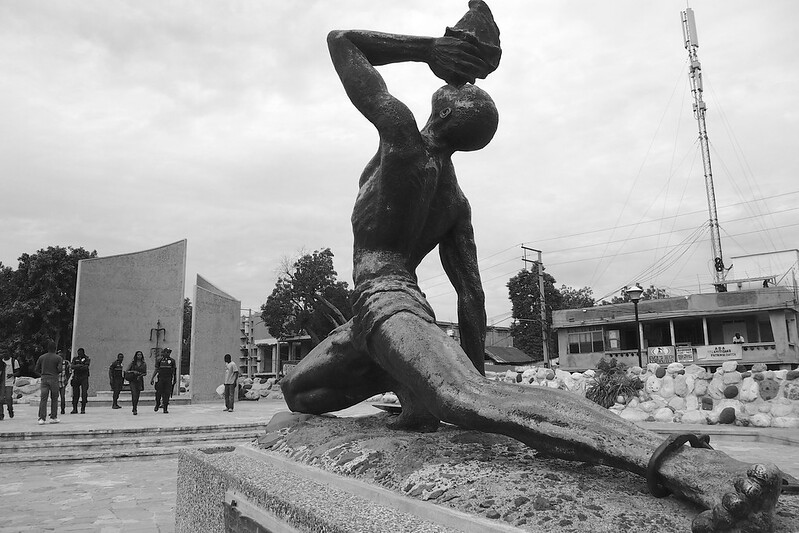

8.10 The Haitian Revolution

All nations tell an epic origin story and Haiti’s Revolution is a story that intertwines the work of maroons, Islam, the emergence of Voodoo, and the fight against colonialism. The story begins in a Haitian forest called “Bwa Kayiman” which translates to “forest near the Imam’s house.” It was named this because it was a location where Muslim prayers and preaching regularly took place. According to legend, a group of leaders met and held a Voodoo ritual that asked Ogun if they should rebel against the white slaveowners. The ritual led to a positive sign from the divine powers and, therefore, the Haitian people revolted against slavery.

The whites on the island were outnumbered twenty to one (Girard 2010, 41). After a long struggle for freedom, the rebellion burned plantations and killed all the white people who enslaved them (Mintz 2010, 91). This revolution is the only instance in human history where enslaved people rebelled and directly caused their own emancipation and Voodoo was a formative cultural force in this success.

8.11 The Haitian Origin of Zombies

It may surprise you to learn that Haitian culture invented the zombie (Davis 1985). While the zombies in American popular culture are re-animated corpses seeking to sustain themselves on living flesh, the Haitian concept of the zombie manifests in a very different, and much more terrifying, way.

In the Haitian Voodoo tradition, a zombie (spelled “Zombi” in Haitian Creole) is a person who has been fed a potion from a Voodoo priest-for-hire (or a “Bòkò”) that makes the victim’s heart appear to stop beating and causes them to present as dead (Davis 1985). After being buried, the person wakes up from their death-like sleep and they are suddenly mindless, compliant, and will do whatever they are told to do (Davis 1985). If you are turned into a zombie, you are essentially enslaved by the person who hired the Bòkò and you will spend the rest of your days doing whatever they tell you to do (Girard 32; W. Deseme, personal communication, July 2020).

Becoming a zombie is the greatest horror in Haitian culture. An interview with Haitian community leader, Willio Deseme explains,

“The real death is when you die and your body and soul are free. But, when you are a zombie you are not alive, but you are not dead. It’s bad because you’ll become a slave and they will sell you. You will be forced to work for the rest of your time until the Bòkò who zombified you is dead. So, you could be a zombie for more than 20 years, and they will use you for a variety of things.”

Zombification in Haiti is often described in the following way, “Slavery is a fate worse than death.” From this belief in and fear of zombification, we can understand that the Haitian people see the human spirit as inherently free and the greatest tragedy is to be enslaved. They would, understandably, rather be dead than a slave.

The fear of zombification is ever-present for two reasons. First, as any fan of Haitian culture knows, there are two documented cases of Haitian people being zombified. The first was Clairvius Narcisse who was pronounced dead by two doctors (including an American doctor) and was buried after multiple days. Eighteen years later (1980), Narcisse returned home and explained to his family that he had been living under the spell of zombification (Davis 1985). Second, a similar event took place in 1979 when Francina Illeus was found alive in a marketplace after having been pronounced dead and buried 3 years earlier (Ibid).

Those two extreme cases aside, the Haitian person similarly lives under constant threat of exploitation from the global economy and international development sector which seeks to mold and “improve” them (or, in other words, to make them do whatever you say).

Exercise 8B

Learn more about the origin of zombies with this episode of Throughline. For more details, read NPR’s article titled, “Tracing The History Of ‘Zombie’ From Haiti To The CDC.”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- What, in your view, is the function of the belief in zombies? What mysteries are solved by believing in and talking about zombies?

- How has the concept of the zombie changed over time? What does this tell you about our ever-changing changing societal, economic, and political climate?

8.12 Ghosts versus Zombies

If, as anthropologists, we ask the question, “what is a ghost?” we will discover that there is no one, singular definition of “ghost” that is common across all cultures. In the United States, a common definition of “ghost” is “a disembodied soul”. But, even that particular definition of ghost is not universal when we start to ask clarifying questions such as, “Where does the soul reside?”, or “How big is the soul?”, or, even “How many souls do we have?” In the U.S. we don’t often talk about death, dying, or the soul. Most Americans have an idea, but these ideas are usually personal and not universal. For many, we form an idea that makes sense to us but we rarely discuss or even reflect on further. For instance, consider the belief that your soul is the size of your entire body and resides in all the tissues. If this is the case, if you cut your hair or nails, does part of your soul go away? What about as you grow, do you somehow have more soul than an infant? What about if you donate an organ to another, does part of your soul go with it? These are all subjective questions to which one is likely to get as many answers as there are people answering them.

In the United States, ghosts and zombies are usually considered to be souls without bodies and bodies without souls, respectively. Thus, they are essentially opposites. For many, ghosts are more fear inducing than the shambling hordes of zombies portrayed on movies and TV (more on that below). But, why are ghosts so frightening? Consider the earlier point that ghosts are defined in unclear terms. If ghosts do not follow clear, universal rules then we feel that we are facing an unknown threat whenever we perceive of ghosts! The old adage, “we fear what we do not understand” is precisely what is at play with this particular fear . Consider the following unknown rules surrounding ghosts: Can ghosts move objects as well as move through objects? Are they tied to a certain place, or can they move around freely? Are they trapped or are they angry? Why are they in a certain place and not others? Where is a safe place? Can they hurt us? Obviously, we have more questions than answers (assuming ghosts exist at all). Furthermore, there is not much agreement on what ghosts can do because whatever “evidence” of ghosts exists are usually a singular, eyewitness accounts that may be are inaccurate at best or completely fabricated at worst. There is no way to scientifically examine the existence of ghosts because there is no objective, measurable evidence available.

On the other hand, zombies are believed to follow a more clear cut, universal, and reliable set of rules. . The word “zombie” derives from Central or West African and Haitian culture and refers to the concept of a human body acting outside of it’s normal, biological control. Haiti, in particular, has a very complex history involving slavery, revolution, and a cruel cash crop industry of sugar cane. The harvesting of which was very difficult and deadly work in the hot, humid, and malaria ridden tropics. It was here that the concept evolved into the Voudou version we associate it with today. What many don’t realize is just how much of American zombie lore directly stems from mass media and in particular George Romero and his modern reinvention of what a zombie is. Prior to the “Night of the Living Dead” (an independent film that burst on the scene in 1968, just in time for Halloween) the predominant ideas of a zombie were much more in line with the traditional sense of the word. A zombie was essentially a mindless worker, created through the magic of Voudou, who would slave away at the behest of the controller/ creator (a sorcerer called a Bokor), with an overt master/ slave association, to work their “lives” away in the sugar fields. To get a much better idea of the more traditional use of the term see “The Serpent in the Rainbow” or even “White Zombie”. In these instances, the zombie itself was not the scary part, becoming a victim of a Bokor and being turned into a zombie was the most terrifying aspect!

In the post-Romero sense of the zombie, we now see the shuffling hordes of the virus induced dead bodies that slowly ramble around looking for brains of living beings to feed on. The emphasis has shifted from an evil sorcerer to a scientific/ governmental mistake becoming the creator and the zombies themselves becoming the villains. These slow-moving, dim-witted, and easy to evade predators are given the quite impossible task of somehow biting through the skull to consume brains as their primary mission. They can only be stopped by severing the brain, which has ostensibly been “hijacked” and is mechanically controlling the movements of these creatures (supposedly a more believable scenario to modern audiences than one involving magic). These still retain a hint of the traditional fear in that, if bitten, one becomes infected and thus becomes a zombie themselves; however, this aspect has been usurped in a large part by the more mundane fear of being eaten alive. All of this is eclipsed by the idea that anyone can survive an encounter through quick thinking and action. This is probably one of the most comfortable apocalyptic scenarios for most people (which likely explains its popularity) because most of us assume that we could survive it. The “Romero zombies” have shifted the monster away from the creator/ controller of the zombies, to the zombies themselves.

In conclusion, the unknown nature of “ghosts” sets them apart as a unique belief system that is not as universally defined as the concept of the “zombie” which has been more clearly defined by Hollywood influences. While some might believe in the existence of both ghosts and zombies, the more predictable nature of zombies allows individuals to feel a sense of control and – therefore – survivability when encountering a zombie.

Exercise 8C

Ghost stories reflect a great deal about our worldview. Listen to NPR’s story titled, “The Truth That Creeps Beneath Our Spooky Ghost Stories.”

Then, see if you can answer the following questions:

- Which senses are discussed in these stories? (Smell, sight, touch, taste, sound)

- Are the spirits in these stories considered to be malevolent? Or benevolent? In which circumstances? How do you know?

- In your view, do the tellers of these stories believe in souls? Why or why not?

8.13 Voodoo in the United States

The Haitian slave revolt in the late 18th and early 19th centuries had created fears in the United States, where slavery was still practiced, so the goal was to politically isolate Haiti. During the slave revolt, the U.S. government, under the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, provided aid to the French colonists fighting against the slaves to suppress the revolt and reinstate slavery in Haiti. Jefferson was a supporter of the French Revolution and its ideals, but opposed the freedom of slaves in Haiti since he and many of his supporters were slave owners. Despite the success of the slave revolt overthrowing the French colonial rule and creating an independent state, Haiti was not recognized by US as an independent country until 1865, 61 years after its independence. The thirteen-year slave revolution in Haiti led to large numbers of Haitians migrating to the United States, due to turmoil on the island. Many of the refugees arrived in Louisiana, bringing along their culture and religion. This was the first exposure Americans had to Voodoo.

8.14 The History of Rastafarianism

An important syncretic revivalist movement that occurred in the Caribbean was the Jamaican Rastafari movement. Revivalist movements are attempts to revive a past golden age, with the belief that ancient customs represent the noble features and legitimacy of the repressed culture. The movement was in response to slavery that existed on the island. Very early history of Jamaican slavery is similar to Haiti. Enslaved people were transported to the island by Spanish colonizers from West Africa. Under Spanish rule, enslaved people were forced to learn and convert to Christianity. During this period there were indigenous populations on the island, who were almost completely wiped out by disease and violence from contact with the Europeans shortly after the transport of enslaved people from West Africa. As a result, the transported enslaved West African people did not have much contact with the indigenous population. The transport of enslaved people to the island coincided with European Jews travelling to Jamaica around this time to work in sugar production as indentured servants, who later became owners of sugar plantations. Many fled Spain during early expeditions as a result of the Spanish Inquisition. This resulted in increasing contact between European Jews and enslaved West African people, which played a role in the development of the Rastafari movement later in history.

English forces took over the island in 1655. The English plantation owners prevented enslaved people from learning Christianity, because they feared that Christian teachings would encourage the slaves to revolt. This means that enslaved people and formerly enslaved people continued practicing African religions, because they were not forced to convert to Christianity. Slavery was abolished in 1838 in Jamaica. This was followed by the Christian evangelical movement of the Great Awakening, which swept through North America during the 1860s. This movement led to black churches being formed in Jamaica, where thousands of ex-slaves converted to Protestant Christianity.

Jamaica remained under British colonial rule until 1962. During this period a small white elite population ruled the island, with a small black elite community and a large impoverished black population. The socio-economic conditions of the island resulted in the development of Rasta ideology among the working class and poor black population.

Marcus Garvey (1887 – 1940) was an important figure among the working-class black people of Jamaica. He was a political activist, journalist and publisher. Garvey was born in Jamaica to a working-class family. His family was considered to be on the lowest end of Jamaican social hierarchy, which was based on skin color. In 1914, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). His goal was to create a worldwide fraternity of Black people and promote race pride to restore their lost dignity. Garvey believed that Africa was a place for repatriation for black people and predicted that a “black king” would one day be crowned in Africa. This prediction was followed by an event in Ethiopia that confirmed Garvey’s argument for many of his followers.

In 1930 Prince Ras Tafari was crowned as the king of Ethiopia. Upon his crowning Ras Tafari claimed himself as Emperor Haile Selassie, which means “Mighty of the Trinity”. Haile Selassie’s crowning as emperor was seen as fulfillment of Marcus Garvey’s prophecy in the Americas, especially in Jamaica.

During this period the Rastafarian movement begins and gains followers. Haile Selassie gives himself the titles of King of Juda and the King of Kings of Ethiopia and Elect of God, linking his lineage to Solomon and Sheba. These events and titles are perceived by the Rastas as confirmation of Selassie being the messiah prophesized in the Old Testament.

Leonard Howell (1898 – 1981) aka The Gong was one of the first Jamaican preachers of the Rastafarian movement. In the 1930s, shortly after Ras Tafari became the emperor of Ethiopia, Howell preached that Haile Selassie was “the Messiah returned to earth” and Ethiopia was the promised and idealized land. Howell was arrested and jailed for two years for expressing hatred and contempt for the Jamaican government in his preaching. Upon Howell’s arrest his Rastafari followers withdrew to rural Jamaica and formed the Pinnacle Commune.

8.15 Examining the sociocultural context as a revivalist movement through symbols

Modern Jamaican society was borne out of slavery. Jamaican Black people lived in the periphery of the colonial world. They were economically depressed, dominated by a small elite white population and a British colony until 1962. Starting in the 1930s and intensifying in the 1960s there was a rise of Black nationalism in Jamaica in response to these conditions. The rising Black nationalism was a resistance to globalization and British Protestant rule. The resistance to British Protestant rule is apparent in many of the important Rasta symbols.

- The “Lion of Judah” is one of the most important Rasta symbols, which represents the maleness of the movement. Rastafari is a male dominant movement and women are typically in the periphery.

- History plays an important role in the Rastafari movement, making it another important symbol. African history is considered to be deeper than Christianity and older than Judaism. This revivalist movement connected itself to African history, which predated the history of slavery and domination by Europeans, as a response to European colonialism.

- Sins of Babylon – Babylon is considered to be the place of bondage, which represents the white imperialistic political power structure exploiting and holding people, especially Black people, back for centuries.

- Zion is the counter to Babylon in Rastafari, a utopian place where there is unity, peace and freedom. Ethiopia is considered to be the Zion for the Rastafari movement, believed to be the original birthplace of humanity. The only path to redemption from Babylon is repatriation to Ethiopia.

- Jah is the Rastafarian name for God and is the symbol of triumph over tribulations of everyday life.

- The Holy Herb – Ganja – is not smoked recreationally in Rastafari, contrary to popular belief. It is ritually smoked for spiritual reasons and medicinal purposes. Use of Ganja is based on several passages from the Bible that are embraced by Rastas as reasons for use of the herb. These include: “…thou shall eat the herb of the field.” (Genesis 3:18), “He causeth the grass for the cattle, and herb for the service of man.” (Psalms 104:14)

- Dreadlocks are another important symbol of the Rastafari. This is a type of hairstyle where hair is twisted into locs or braided. Dreadlocks symbolize Rasta roots and are a symbol of the Lion of Judah, because their form resembles a lion’s mane. This hairstyle is a rebellion of the system and the “proper” way to wear hair according to the white elites of the society, so they are a sign of resistance and outsider status.

8.16 Exodus and Jamaican Rasta Captivity

Early Jewish and West African people’s interaction during the early history of Jamaica has had an important influence on the beliefs and symbols of Rastafarians. Exodus is one of the most prominent beliefs that illustrates Jewish influence. Rastafarians in Jamaica identified with the captivity of Jewish slaves in Egypt and Babylon due to their history of slavery, bondage and domination by European colonialists. As a result, Exodus has become a central Biblical myth for Rastafarians with a call for freedom from oppression in Jamaica. Popular Jamaican reggae artist Bob Marley’s song Exodus revolves around this Biblical story.

When tracing the history and rise of Rastafari as a revivalist movement we understand how it has become a religion of resistance to domination and slavery, similar to several other syncretic Afro-Caribbean religions in neighboring islands. However, its form is different from the other syncretic religions and this is due to the British colonial rule in Jamaica. Many syncretic Afro-Caribbean religions incorporate numerous elements of Christian symbols and beliefs. These groups were originally ruled by Catholic colonial powers, whether it was Spanish, Portuguese or French. Catholicism is more fluid and accepting of modifications of symbols, allowing different cultures to adopt many of its elements and adjust them to their indigenous religious beliefs and practices. Jamaica, however, was dominated by Protestant British rule that prevented the slave population from learning Christian teachings. Conversion to Christianity happened much later and they were through Evangelical Christian teachings. Unlike Catholicism, Protestant and Evangelical Christianity do not allow for modifications, not leaving much room for fusion of old religious symbols and traditions with the new religion.

The revivalist movement of Rastafari that developed later directly challenged Protestant and Evangelical Christian religious ideals. This was done to restore the lost racial dignity of the black population that according to Rasta beliefs was lost during European domination.

8.17 Syncretism in the Celtic World

Why does a Celtic cross (found in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales) look different from a traditional Christian cross that we see elsewhere in the world? The people of the United Kingdom are primarily Christian, so why are their symbols of worship different? Christianity in the British Isles is usually attributed to Saint Patrick who ostensibly introduced it to the Celts in the 4th or 5th century (Flechner 2019). The Celtic cross (along with many other symbols) is a classic example of syncretism of the Christian and Celtic faiths. As we have seen, syncretism is the blending of separate belief systems in an effort to assimilate a group of people into a different religion.

The Celtic cross is one of the most obvious symbols of the syncretism between the druidic Celts and the incoming Christians. First, it’s important to realize that the Celts didn’t have a single, unified culture. They were a diverse group with similar but varied beliefs. The Druids were akin to a priesthood from different sects. Furthermore, they were not writing things down so observations (and assumptions) by the incoming colonists are all that modern historians have to go on. What we do know is that the Celts were primarily an agricultural culture thus their beliefs were closely tied in with natural phenomena (such as weather and seasons) as well as death, birth, prosperity and fertility. The Celtic cross is the merging of a Christian symbol (the Cross) and a Celtic one (the Sun Disc) which we see often in Pre-Christian art (Timberlake 2006).

Some of the other, less prominent syncretic symbols from the Celtic world include: the Shamrock (cloverleaf), the Gaelic Festival Knot (St. Brigid’s Cross) and the Carolingian or Maltese Cross. Let’s take a closer look at some of these.

First, the cloverleaf (suggested by St. Patrick to be a symbol of the holy trinity) is associated with two Celtic symbols and likely at least one Norse one (the Triquetra, the Triskele and the Norse Valknut). All of these symbols are essentially a triangle representing three of a kind. The meanings shift from culture to culture but fundamentally the meanings are associated with fertility; life changes (e.g.; the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone); the elements (e.g.; earth, fire, water), life, death, rebirth, etc. Since this is a generalized “rule of threes” it was not a big leap for the missionaries to associate it with their Holy Trinity.

Next, the Gaelic Festival Knot / St. Brigid’s Cross is depicted as a square, woven from natural sticks or reeds with arms protruding from the four corners. In Christian doctrine, it is a cross used to bless a person or place from evil. The Celtic dogma associates this symbol with the four major festivals marking different seasons (Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine and Lughnasadh).

Finally, the Maltese or Carolingian Cross, not surprisingly the Christians consider this to be yet another crucifix (they are fairly open with the acceptable shape), but to the Celts this is one of their most ancient symbols. While the original Gaelic name of this is lost, most call this the Eternity Knot or the Quaternary Knot representing eternity or everlasting love.

This is not an exhaustive list of all of the syncretic symbols, festivals or even gods shared between these distinct cultures. When people move around the world and meet others, they often try to find common ground and syncretism is often a major aspect of that. Here is a final thought: the Celtic goddess of fertility is Ēostre (Sumerian: Ishtar), her symbols include the rabbit and eggs (both of which symbolize fertility) and her festival is in the Spring, sound familiar? Here’s a hint: Easter isn’t exclusively about the resurrection of Jesus!

Exercise 8D: Journal Reflection

Closely examine your cultural and religious identities and try to trace the global influences (migration, colonialism, power dynamics) that have shaped how you engage with your cultural identity and religious practices. Recall the concepts “syncretism,” “domination,” “assimilation,” and “acculturation” and try to use at least one of these terms in your response.

Exercise 8E: Study Guide

Before moving on, ensure that you can define the following terms in your own words:

- Syncretism

- Domination

- Salvage Anthropology

- Assimilation

- Acculturation

- Voodoo

- Vodouisant

- Taíno

- West African Spirit Worship

- Orisha

- Loas

- Papa Legba

- Ogun

- Damballah

- Erzulie Danto

- Revivalist movements

- Lion of Judah

- Sins of Babylon

- Zion

- Jah

- The Holy Herb/Ganja

- Dreadlocks

- Exodus

- The Celtic cross

Chapter 8 Works Cited

- “Haiti: Travels in a Land Where Black Rules White”. The New York Times (March 9, 1901). ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times.

- Davis, Wade. 2008. The Serpent and the Rainbow. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

- Desmangles, Leslie. 1992. The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Farmer, Paul, et al. 2012. Haiti after the Earthquake. PublicAffairs.

- Girard, Philippe R. 2010. Haiti: the Tumultuous History–from Pearl of the Caribbean to Broken Nation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Long, Carolyn Morrow. 2015. “Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment, and Religion”. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 6, no. 1: 86-101.

- “Look to the East – Haile Selassie and the Rastafari Movement.” 2018. AllAfrica.Com, Nov 05.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1985. Sweetness and Power. Viking.

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred. 2012. Three Ancient Colonies: Caribbean Themes and Variations. Harvard Univ. Press.

- Osbey, Brenda Marie. 2011. “Why We Can’t Talk to You about Voodoo”. The Southern Literary Journal 43, no. 2 (2011): 1-11.

- Rouse, Irving. 1992. The Tainos: rise and decline of the people who greeted Columbus. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Stein, R.L. and Stein, P.L., 2017. The anthropology of religion, magic, and witchcraft. Routledge.

- Zunner-Keating, Amanda. “Interview with Willio Deseme.” 5 July 2020.

Chapter 8 Suggestions for further reading:

- Brown, Karen McCarthy. 2010. Mama Lola: a Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. University of California Press.

- Buck-Morss, Susan. 2009. Hegel, Haiti, ; and Universal History. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Dolin, Kasey Qynn. 2001. “Words, sounds, and power in Jamaican Rastafari.” MACLAS Latin American Essays(2001): 55+.

- Dubois, Laurent. 2013. Haiti: the Aftershocks of History. Picador.

- Huffman, Robin. “New Religious Movements & Rastafarianism” Creative Commons licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- Hurston, Zora Neale. 2009. Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. Harper.

- Jacobs, Francine, and Patrick Collins. 1992. The Tainos: the People Who Welcomed Columbus. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Kendi, Ibram X. 2017. Stamped from the Beginning the Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. The Bodley Head.

- Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel. 2010. Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions. Temple University Press.

- Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hafustot “The Jewish Community of Jamaica” https://dbs.anumuseum.org.il/skn/en/c6/e227517/Place/JamaicaSchuller, Mark, and Pablo

- Morales. 2012. Tectonic Shifts Haiti since the Earthquake. Kumarian Press.

- Schwartz, Timothy T. 2010. Travesty in Haiti: a True Account of Christian Missions, Orphanages, Fraud, Food Aid, and Drug Trafficking. BookSurge Publishing.

- Triplett, Mike. 2019. “That time the Saints used a Voodoo priestess to end Superdome curse”. Accessed October 3, 2020.

Written by Amanda Zunner-Keating, Madlen Avetyan, and Brian Pierson. Edited by Jennifer Faux-Campbell and Ben Shepard. Special thanks to Jennifer Campbell for curating photos; Melody Yeager-Struthers for organizing our resources. Student research/editing by Phillip Te. Layout by Amanda Zunner-Keating and Madlen Avetyan. Audio recording by Amanda Zunner-Keating.

NPR links on this are linked NPR’s website with permission from NPR. All NPR content (audio, text, photographs, graphics, videos) is protected by copyright in the U.S. and other countries. For more, visit NPR’s Rights and Permissions website.