3 Linguistic Groups

Camron Michael Amin; Alam Payind; and Melissa McClimans

This chapter is an overview of the diversity of the region in regard to linguistic groups. Local language is a key to mapping the diversity of Middle Eastern identities. While linguistic boundaries do not always obey national boundaries (in the Middle East, more often, they do not), they provide a picture of the diversity of the cultural landscape. Cultural identity and the communities that shape how individuals are seen in greater society go beyond static definitions of culture, ethnicity or nationality, and can easily be oversimplified in an introductory text, such as this one. Focusing on the “cultures” of the Middle East can be quite problematic because boundaries can be hard to define. Further, the notion of a static “culture” notion of culture can lead to categorizations of communities according to “characteristics” that can be misleading (Rogoff,2003). The focus on history is not to relegate these communities to the past, but to incorporate the element of time and to explore an important aspect of culture, language, which exhibits stability and change. Languages convey information about long histories more than national borders do.

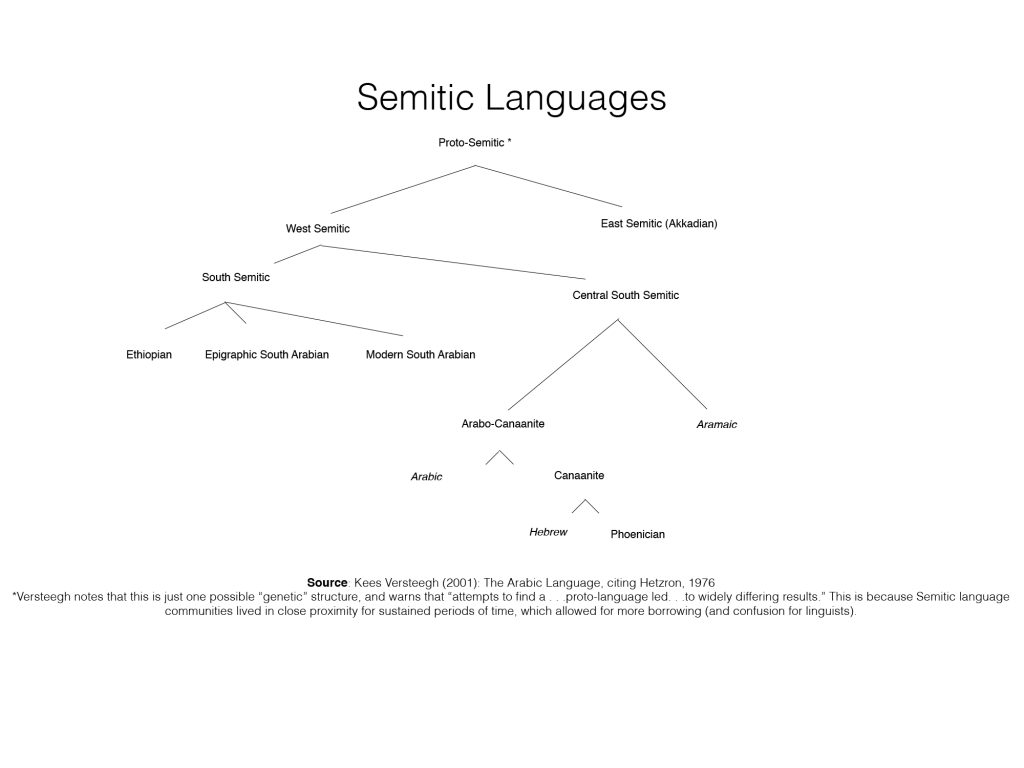

Constructed over time, languages continually change while retaining stable patterns of meaning. Through this process, some communities eventually develop their own versions of these patterns, and lose the ability to communicate with their previous communities, and a dialect is formed. Deep historical connections and divides between cultural/linguistic groups are revealed through evidence found in patterns of speech. Divides occur when two ways of speaking lose their mutual intelligibility, or the ability of one speaker to make him or herself understood to the other and vice versa, they become separate dialects or languages. Languages branch off of the main group, then split again within themselves. When visually rendered, this forms a sort of language family tree (see Middle East language “family trees” below). The issue of when a new form of speech constitutes a new dialect or a full-fledged language is often highly contentious. Many of the Middle Eastern languages we touch on in this chapter consist of numerous sub-dialects, which are mutually intelligible, semi-intelligible or barely at all. It is a spectrum, rather than a definite line. According linguist P.H. Matthews:

“what count as separate ‘languages’ for specialists in one part of the world are often much more like each other than the ‘dialects’ of a single language as described in others.” (2003,p.77)

When such differences are used as grounds for discrimination, or become politicized, it can be challenging to get a straight answer from anyone about the status of a language. Language is profoundly and universally tied to cultural identity and social experience. Be cognizant of this factor as you continue to learn about the languages of the Middle East, and their connections (and dissonances) with national identity; particularly when a language is overtly tied to citizenship and cultural loyalty in the popular culture.

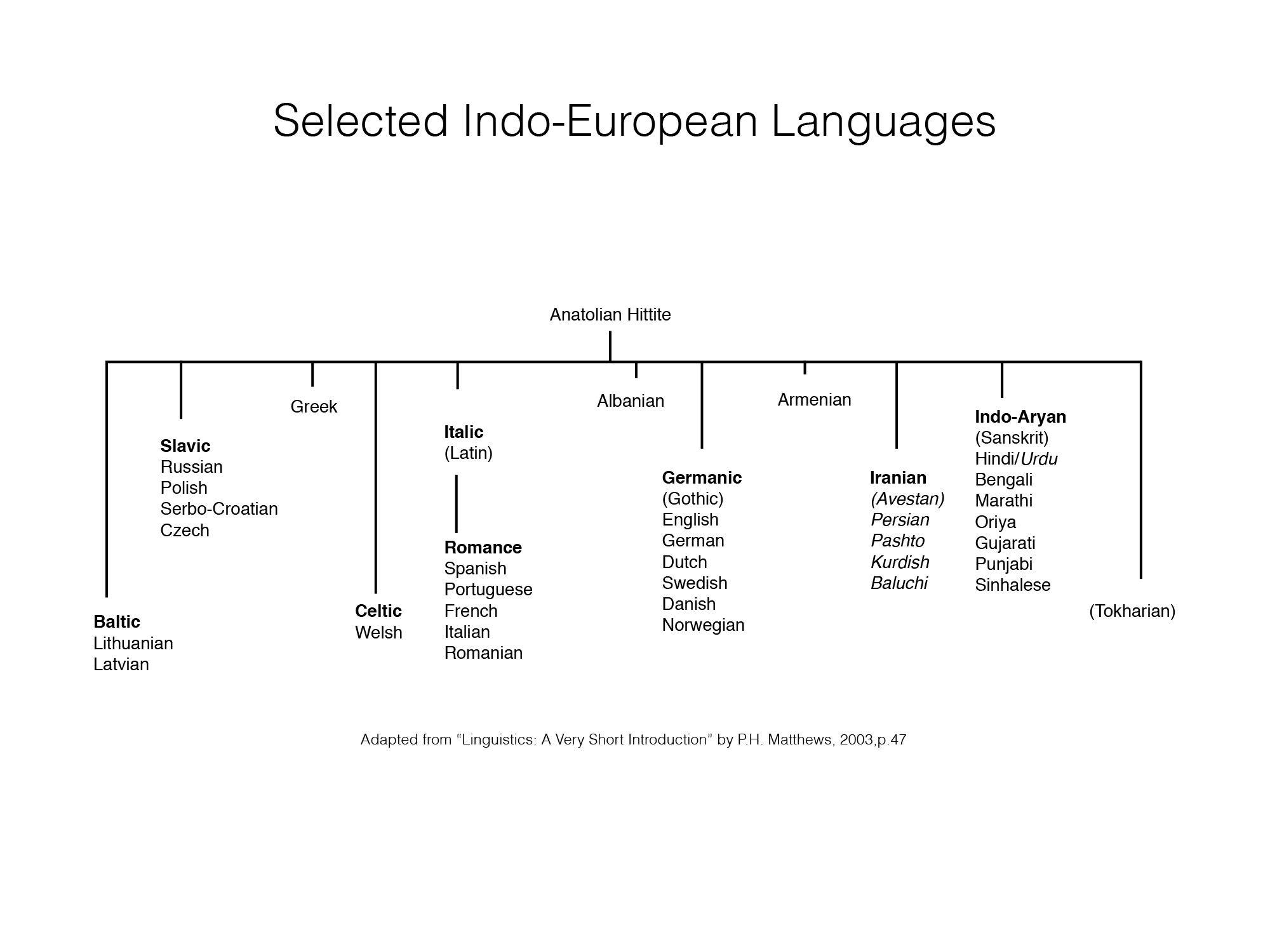

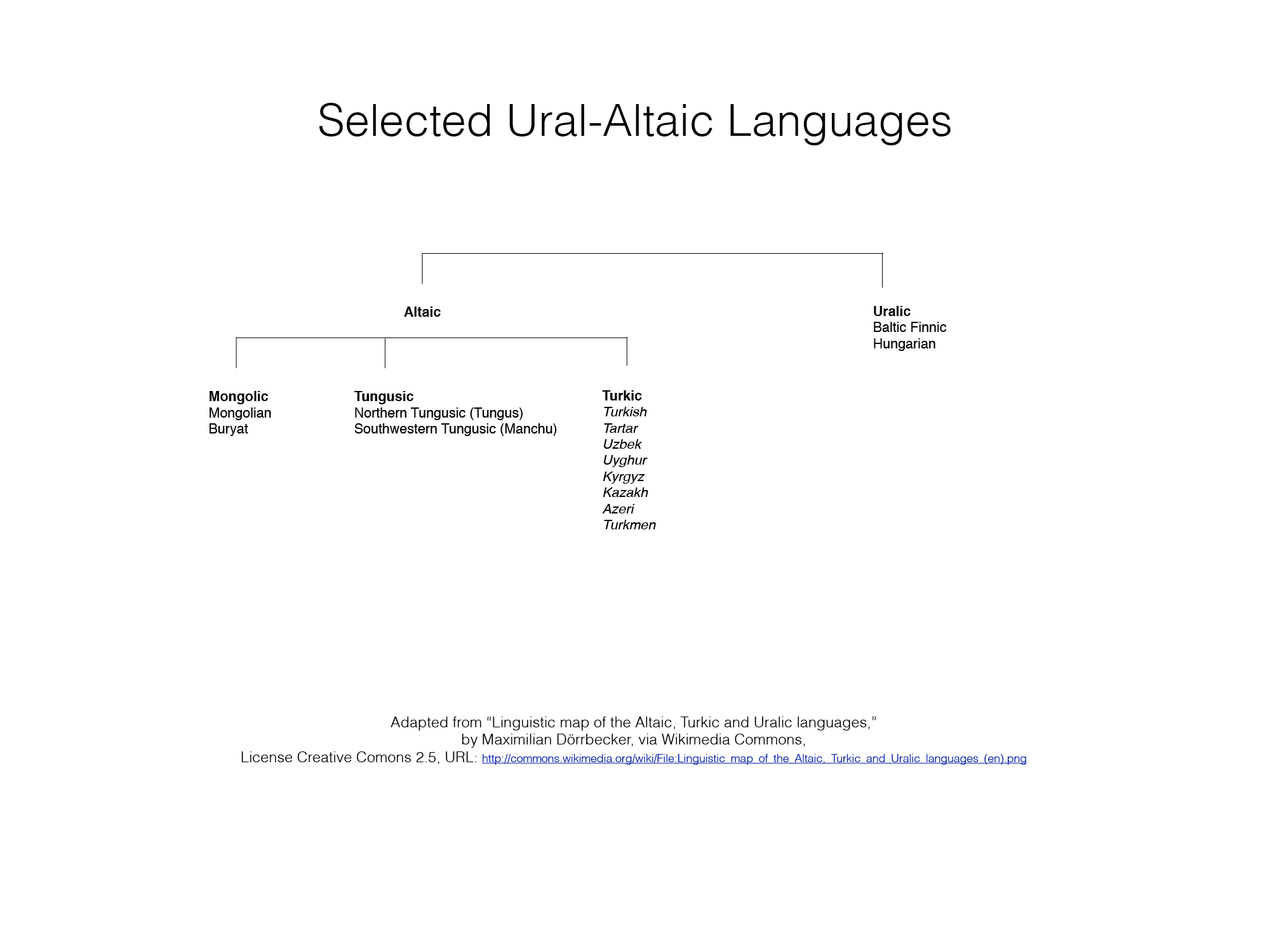

The many languages that exist in the region can be grouped into three large linguistic categories. They are listed below, and we have provided them in chart form below.

- Semitic Languages (Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic/Syriac and others)

- Iranian Languages (Pashto, Persian (Dari, Tajik), Baluchi, Kurdish and others)

- Ural-Altaic Languages (Turkish and other Turkic languages, such as Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Azeri/Azerbaijani).

Semitic languages are important due to the histories of the Ancient Semitic civilizations, such as Sumeria, the Hebrew communities, Arab communities and Aramaic-speaking communities of today. Abraham was an Akkadian speaker, and Jesus’s native tongue was Aramaic. Aramaic is also one of the important languages of the Talmud, or the scriptural exegesis made by prominent Jewish scholars regarding the Torah. Hebrew is the traditional language of the Jewish people, and has become a living language again in Israel, since the late 19th century. It is the language of the central Jewish scripture, the Torah. Arabic is another other majorly influential Semitic language which we will cover in the next section.

Persian is the main language spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. Being an Indo-Iranian language, and part of the Indo-European family of languages, it is much closer to English in structure than the Semitic or Turkic languages. Thus, it takes less time for a native English speaker to learn Persian than to learn Arabic, Hebrew or Turkish. Persian/Iranian words continue to play a major role in the languages of the Middle East and beyond.

In order to put the language “families” in context, consider Persian in relation to European languages – they are both part of the same linguistic “family tree” (see chart, below). It is not hard to deduce that English and Persian have a common ancestor. One of the ways linguists determine a language’s origins is by looking at “old words”; that is, words which represent concepts with a long history in the community. The words for family members are analyzed in this regard, as family experience is a fundamental human experience. The word “daughter” in English reveals through its spelling a previous pronunciation in which the “gh” was pronounced something like the “ch” in German. German retains this pronunciation in its word for daughter: tochter. The Dutch word is dokhter. The word in Persian is also dokhtar. Mother is mādar in Persian, Father is pedar, Brother is barādar. These are pieces of evidence that English, German, Dutch and Persian share a common ancestor, and thus, common cultural community from the distant past.

place holder

Semitic Languages:

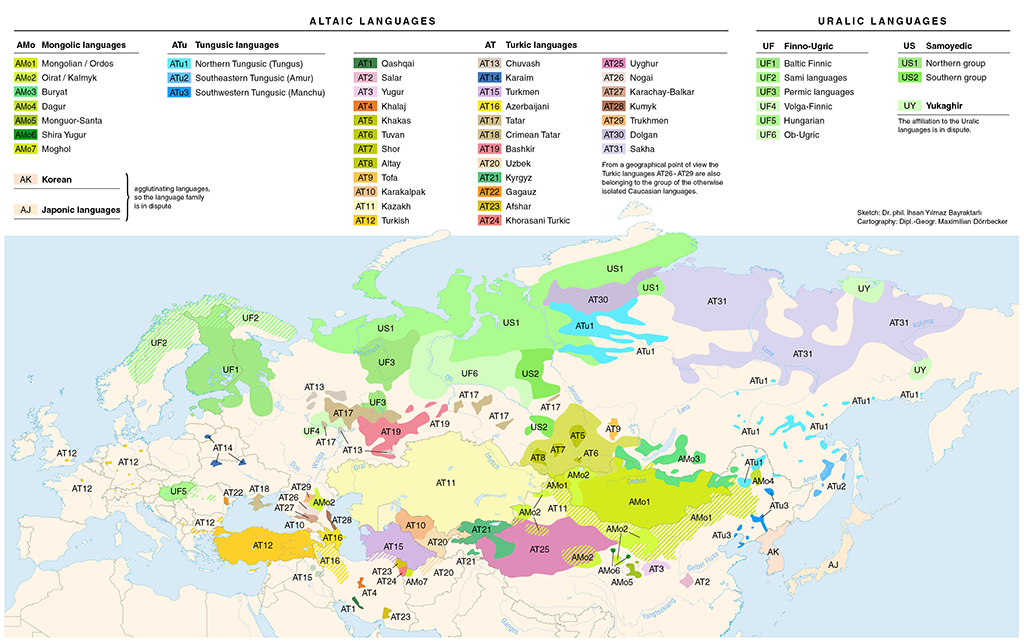

Turkic languages include modern Turkish, and are an additional highly influential group in the region. Rooted in nomadic cultures, Turkic-language-speaking communities migrated westward in waves from Central Asia, over the centuries. These groups made an impact in world history in numerous ways. Mamluks, Seljuks and later Ottoman civilizations enjoyed some of the highest levels of culture, medicine and science in the Middle East region and perhaps the world. These and other Turkic communities took on the leadership of Islamic expansion after the Arabs, eventually taking Constantinople. They made numerous significant contributions to the past and current cultural landscape of the region. The expanse over which Turkic languages spread is remarkable (see map, below), reflecting the nomadic migrations of these communities throughout history.

Map of Uralic, Turkic and Altaic Languages:

Imperial and Administrative Languages in the Middle East

While the movement of people across the Middle East was necessary to the spread of the languages discussed above, it was clearly not sufficient. For a language to become widespread and persist in some standardized form resources are required. Those resources tend to come reliably only from a combination of state and religious institutions. The impact of Arabic was so great on the Middle East not only because of the spread of Islam (conversion of populations took centuries) but because the Arab-Muslim imperial caliphates – fist the Ummayads and then the Abbasids – made Arabic the primary administatrive language of their states and supported institutions of religious and other learning in which Arabic was essential for the training of a whole host of religious officials and functionaries. Before the spread of European Imperialism in the 19th Century, only two other languages gained a comparable level of cultural salience beyond the ethnic groups and locales in which they resided: Persian and Ottoman Turkish. And both these languages were heavily influenced by Arabic in terms of loan words and their orthography, which are based on a modified Arabic script. The difference between Middle Persian and Modern Pesian is, to a large extent, Arabic. The revival of Persian as an administrative and cultural language had a lot to do with the revival of the political fortunes of ethnic Persian elites starting in the 9th Century. The rulers of the Samanid Dynasty were nominally loyal to the Abbasid Caliphate, but in fact, expanded their autonomous control over much of the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia at the expense of the Abbasids. They restored Persian as an administrative language and patronized the cultural revival of Persian in literature, philosophy (broadly defined) and history. This was so much the case that even Turksih ethnic elites like the Saljuq Dynasty which displaced the Samanids maintained Persian alongside Arabic as an administrative and diplomatic language. But, it was the one-time vassals of the Saljuqs, the Ottomans who eventually added Turkish to the short list of administratie languages, with all the other cultural implications that flowed from that. The sheer extent of the Ottoman territory by the Sixteenth Century meant that Ottoman Turkish spread widely even if it did not take deep root locally in much of the majority of the Ottoman Empire in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East that was not ethnically Turkish.

The Relationship Between European Imperialism, Nationalism and Transliteration

Starting in the 19th Century, communities in North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia began to encounter new imperial administrative languages: French, English, Russian. As European (and later American) scholars and journalists, their study of local languages in the Middle East produced competing conventions of romanization/transliteration. In one system, the Arabic word قرآن could be rendered as ḳorʾān in one system and qurʾān in another system, and those got simplified to the two versions of the English word (Koran, Quran) for the Muslim holy book. Some systems of romanization attempt to account for different pronunciations. Persian-speaking Iranians will use the Arabic word for book, کتاب, but pronounce it differently, with the first vowel arguably being better approximated in English with an “e.” So, ketāb, rather than kitāb. But, if you consider the second vowel that leads to another issue with pronunciation. In Arabic, there are simply long and short versions of the same vowel: i/ī, u/ū, a/ā (see A Note on Language). In Persian those vowels sound different. For example, the Arabic long a is rendered in Persian as “aw” – both for words of Persian origin and for Arabic loan-worlds in Persian. For just Persian (and all its versions), there are multiple transliteration schemes available. But, the linguistic differences – as standardized in formal versions of the languages or represented Western scholarship – are not the only complicating factor in how these words can appear in modern Western texts. There are also regional dialects and, in the modern period, nationalist political agendas to consider.

Arabic has more consonants than either Turkish or Persian (though it lacks a couple they possess, like “p”). That has implications for how Arabic loan words were pronounced and spelled when systems of writing were reformed or replaced in some countries, often with nationalist priorities in mind. When Ottoman Turkish was replaced by Modern Turkish in the Republic of Turkey in the 1920s, the “purge” of many (but not all) Arabic or Perian loan words from Turkish was accompanied by a new system of writing: a modified Latin script which prioritizes phonics replaced the modified Arabic script used for Ottoman Turkish. So, the word for “book” in Modern Turkish became “kitap,” with that terminal “p” morphing into a “b” for certain grammatical constructions in Turkish (For example, “my book” is kitabım – and, yes, the undotted “ı” follows in how the phrase would be by pronounced in Modern Turkish. A dotted Turkish “i” sounds like “ee” in English). What this means is that many words from Middle East-based languages that become English words or that are represented in English works of scholarship or journalism can be rendered differently even though they are, in the end, the same word. This issue can be complicated further with names, where regional pronunciations and official romanizations can compete for priority. In Egyptian Arabic, “j” is pronounced as “g.” So, Gamāl ʿAbd al-Nāṣir (sometimes rendered as El-Nasser), not Jamāl ʿAbd al-Nāṣir is often how we see that famous person’s name in textbooks and old press coverage, even though the first name in Arabic print/script is always rendered as جمال.