16 The Middle East and the Impact of Imperialism

Camron Michael Amin; Alam Payind; and Melissa McClimans

Visual Aids for Chapter 3. Imperialism

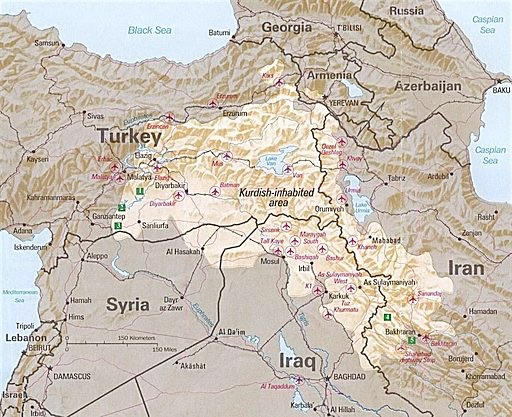

Map: Kurdish Territory

Key Figure: Mossadegh

Key Figure: Ayatollah Khomeini

Images: Modernizing Leaders (Atatürk, Reza Shah and Amanullah Khan)

Key Figure: Gamal ‘Abdul Nasser

Maps: NATO and other Alliances/Treaty Orgs

Before Western Imperialism: A Overview

One way to conceptualize the history of the Middle East from the early 7th Century CE until about the year 750 CE is as the center of religious and political authority for an expanding political order dominated by elites that were mostly-Muslim and mostly Arab. By the year 1000 CE, the political order in the Middle East was more fragmented among differing factions and political elites of a number of ethnic backgrounds. And while many areas in the Middle East were becoming “Muslim majority” societies, sectarian differences among Muslims reinforced some of the political divisions. Furthermore, Islam – in all its forms – was spreading as much my trade and migrating as by conquest. By 1500 CE, it was no longer the case that the majority of the world’s Muslims lived in the Middle East. By 1600, of the capitals of the largest Muslim empires – the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals – only Safavid Empire’s capital, Isfahan, was located in the lands of first caliphal empires.

By 1800, only the Ottoman Empire was still standing as an independent state still controlling vast amounts of territory on three continents. The Safavids had been displaced by an Afghan invasion and decades of civil war that culminated in the rise of the Qajar Dynasty (1796-1925) in Iran. The Mughals had suffered from an invasion by a post-Safavid warlord, Nader Shah Afshar, and then been reduced to a dependency of a corporation – the British East India Company – as a prelude to being formally incorporated into the British Empire in the 19th Century. Again, the Ottomans were battered by global forces and internal divisions in 1800, but the governing institutions and practices they had inherited in the 13th Century (and had steadily reformed after that) served them well. What political legacies did the Ottomans claim as part of their own legitimacy? That is a not simple question, but we can begun with a simple, pre-Ottoman political timeline:

Life and Career of the Prophet Muhammad, 570-632

The “Rightly Guided” Caliphs, 632-661

Abu Bakr, 632-634

ʿUmar, 634-644

ʿUthmān, 644-656

ʿAlī, 656-661

The Umayyad Caliphate, 661-750

The Abbasid Caliphate, 750-1256

The Ottoman Empire, ca. 1280-1924

Although the Ottomans governed a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional empire, they firmly tied their legitimacy to being just Islamic rulers (interchangeably using the Arabic term ṣulṭān and the Persian term padeshah/padişah) and the true heirs of the first Muslim caliphs. The term caliph (khalīfa) was claimed by successors to the Muhammad, and implied a blend of religious and temporal leadership. Caliphs, however, were theoretically constrained by the precedents of the prophet’s teachings and the Koran. But, the earliest caliphs all had both familial ties with Muhammad and had been early followers before his political control of Arabia was secured in 630 CE. They were sources for reports on Muhammad’s actions and teaching; they were recognized as caliphs after a period of consultation with other elites of the Muslim community and after receiving oaths of allegiance from the Muslim community as a whole. From the selection of the very first caliph, Abu Bakr in 633 CE, there was a measure of dissent that broke into the open following the assassination of the the third Caliph, ʿUthmān, in 656 CE. The fourth Caliph, Alī (who was both the cousin and son-in-law to Muhammad) immediately faced a challenged from Uthman’s Umayyad relatives, led by Mu’awiyya. The term shia derives from the phrase, shiʿat Alī (“faction of Alī,” to contrast with Mu’wiyya’s faction) and eventually came to refer to a sect of Muslims that believed not only that Ali’s caliphate was legitimate, but also that Alīshould have been the first caliph all along owing both to his specific designation as caliph by Muhammad and his marriage to Muhammad’s daughter. For the Shiʿa, the fourth caliph was the first rightful Imām, “leader.” For Shiʿa all legitimate Imams we’re both designated by a predecessor and descendants of Alī and Muhammad’s daughter, Fatima. The term imam is used widely to designate various kinds of leadership, but it has a more reserved meaning in what eventually becomes Shia theology.

The dispute in 656 was resolved neither by war or negotiation and, in fact, led to the formation of a third group of dissenters, known to history as the Kharijites (for “those who left” Ali’s camp), who rejected ʿAli’s efforts to reconcile with the Umayyads because they believed Uthman’s death had been just. It was a Kharijite assassin who ended Ali’s caliphate and life in 661 CE. Mu’awiyya took advantage of the ensuing chaos and established himself as caliph. More than that, Mu’awiyya and his successors were able to establish a de facto dynasty. Yes, the rituals of selecting a caliph observed by the first four caliphs were observed, but the outcome was rarely in doubt. And, when it was, it was settled through war. Aside from their own internal disputes, the Umayyads presided over an expanding empire. They crushed or contained dissent from the Shia (notably at Karbala in 680 CE, which resulted in the death of Alī’s son Husayn – the third commonly recognized Shia Imam) and the Kharijites (who over the centuries persisted in North Africa and, eventually, Oman as the Ibadi sect of Islam). They also began to establish traditions of governance that blended Byzantine precedent, Arab tribal coalition politics, Sassanian traditions of kingship and evolving traditions of Islamic law. It is under the Umayyads, for example, that Arabic became the uniform language of governance.

Dissent from Umayyad rule took many forms, but one common growing grievance was among non-Arab converts to Islam, who wanted their second-class status in the taxation of property (which dated to terms of surrender during the Arab Muslim conquests) and among provincial Arab elites who wanted more autonomy from Umayyad oversight. Beginning ca. 750 CE, one family descended from an uncle of Muhammad, al-ʿAbbās, was able to harness a coalition of the disaffected and overthrow (and massacre most of) the Umayyad elite. The Abbasid Caliphate, established their capital in Baghdad and proceeded to consolidate their power at the expense of many of their allies, especially the Shia, whose doctrinal claims to the Imamate they could not abide. Because it was the longest lived caliphal dynasty, the Abbasids are most closely associated with Islam’s classical age, establishing precedents of governance that persisted in modified form in the Middle East right through the onset of Western imperialism in the 19th Century.

Though the Abbasids persisted until the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1256 CE, it is important to recognize that their rule was heavily contested. There were rival caliphates. There was an Umayyad one in Spain in the early 10th Century CE established by descendants of those who survived the Abbasid massacre in the 8th Century and kept Spain independent of Abbasid rule even before declaring their caliphate. Indeed, the Umayyad Caliphate in Spain have felt pressure to claim caliphal legitimacy not so much from the Abbasids, but from a Shiʿa Caliphate in North Africa: The Fatimids. The Fatimids were a distinct sect of Shiʿism That split off from the rest of the movement in the late 8th century. They are known as the Seveners or Ismaili because they followed a different seventh Imam (Ism āʿīl ibn Jaʿfar) than other Shia at the time (who followed Mūsā ibn Jaʿfar). The Fatimids claimed to be representatives, then manifestations, of Ismail, imbued with his charisma and authority pending Ismail’s return from occultation. They named their dynasty after Muhammad’s daughter, Fatima, and established the city of Cairo as their capital in the early 10th Century. When the Sunni Abbasids targeted Shia opponents after the 10th Century, they were most concerned about Ismaili Shiites, both the Fatimid Dynasty in North Africa and Syria, and Ismaili enclaves established in Syria and the Iranian Plateau with direct ties to the Fatimids.

Within territories directly controlled by the Abbasid, there were two sources of opposition. First, there were provincial elites that sought de facto autonomy under the auspices of nominal loyalty to the Abbasids. Their power in the Iranian Plateau increased over the course of a long civil war between rival Abbasid Caliphs al-Amīn and Al-Mamūn in the 9th Century. With aid from provincial elites in Khorasan, Al Mamūn prevailed in 813 CE. For this aid, the elites in Khorasan and the southern Caspian Sea coast wanted and received hereditary governorships which morphed to local kingdoms that vied with each other for both territory in the provinces and influence in the Abbasid Court. Second, there were growing numbers of slave troops of Central Asian Turkish origin pressed into the service of both the Abbasids and provincial rulers. Eventually, a coalition of Islamized tribes known as the Saljuqs swept into the Iranian Plateau in the 11th Century. In exchange for delivering the Abbasids from the control of the Twelver Buyid Dynasty and Fatimid influence from 1055-57 CE, the Saljuq leader Tughril (d. 1063) obtained the title ṣulṭān (the one who rules – on behalf of the caliph by implication).

And so, Islamic caliphal legitimacy came to coexist uneasily with Islamized traditions of monarchical legitimacy. Maps of the later Abbasid Empire and Saljuq Empire overlap because the Saljuqs were ostensibly champions of the Abbasids, Hanifi Sunni Islam and a Turkish confederation that inherited Persian traditions of sacral kingship from the autonomous provincial dynasties they displaced. To complicate political matters further, the Saljuq Confederation split into several rival states over the course of the 12th and 13th Centuries. One of these states based in Anatolia, the Saljuqs of Rum, were the sultans to which the Ottomans were vassals in the wake of the Mongol invasions in the 13th Century, It is when the Ottomans make their own bid from autonomous rule in NW Anatolia in ca.1280, that they claimed the titles of first prince (amīr) and then sultan, which in the absence of Abbasid legitimacy was effectively synonymous with kingship. Their claim to Islamic legitimacy was bolstered by their conquests in the majority-Christian Balkans and Central Europe starting in the 14th Century and the conquest Istanbul in 1452, from which the Byzantine Empire had stubbornly resisted Umayyad, Abbasid, Saljuq (and even Western European Crusader) attempts.

So,where did the Ottoman claim to caliphal authority come from? As was the case with the Umayyads centuries earlier, a member of the Abbasid elite survived massacre and wound up in the protection of the Mamluk Dynasty in Egypt, The Mamluks were a coalition of slave commanders who has displaced the Ayyubid Dynasty in Egypt (which had displaced the Fatimids) while gradually whittling down Western European Crusader kingdoms that that persisted in Levant since the first Crusader conquests in 1099. Having an Abbasid “shadow Caliph” under their protection as they both expelled the last Crusaders and resisted Mongol incursions into Syria bolstered Mamluk assertions of sultanuc legitimacy. When the Ottomans conquered the Mamluks in 1517, and began to consolidate their control over Syria, the Arabian Peninsula (including Mecca and Medina) and North Africa, they also began to link the Abbasid line with their own imperial line.

Aside from these traditional claims to political authority, the Ottomans innovated systems of governance based on classical Abbasid-Saljuq models. For example, from the classical practice of designating funds from state land to compensate loyal local administrators and military officials (known as iqtāʿ land, which may be considered analogous to a fief in the European context), the Ottomans created an elaborate military patronage system that endured formally until the 19th Century (thought it had ceased to function effectively in the 18th). Ottoman practices of limited autonomy for some religious minorities endured until the 19th Century also. At the same time, the Ottoman practice of forced military conscription among Christians in the European provinces both bolstered the power of Ottoman Sultans and created a military institution (the Janissary Corps) which became an independent faction at court, the murderous suppression of which troubled the reigns of Selim III (1789-1807) and Mahmud II (1808 -1839). The rise of European maritime trading empires, fueled both by industrialization and a global competition for markets, raw materials and “prestige” to maintain its own balance of power on the European continent with colonial expansion around the world, put additional pressures on the Ottoman administrative traditions. The Ottomans were largely unsuccessful in fending off encouragement on their territory or separatist tendencies despite costly top-down reform efforts that bankrupted the Ottoman Empire by the 1880s, putting a portion of its state revenues in the hands of European creditors until the outbreak of World War I. The Ottoman Empire on the eve of World War I was smaller but also contained many of the most modernized parts of the Middle East. The characterization of the Middle East as having “fallen behind” economically (in tandem with its political woes) is only true in comparison with Western Europe and the United States. By certain measures – population and economic productivity – the Middle East was growing, including in parts still controlled by the Ottoman Empire.

The Middle East Map of Today

After the First World War, the contours of the major nation-states of today’s Middle East were delineated. It is important to note, however, that WWI did not create the nationalist impulses that sometimes resulted in the formation of nation-states. National ideologies formed in the 19th Century in response to the emergence of nationalist ideologies in Europe (beginning with the French Revolution), in reaction to Ottoman efforts to thwart separartist movements (first those of Christian majority territories like Greece and Serbia and later among Arab and Kurds and Armeians) and in resistance to European imperialism (in North Africa and Egypt and eventually in the parts of the longest-held parts of the Ottoman Empire). Going into WWI, there were multiple models of how the Ottoman Empire might persist through its modern challenges, including notions of decentralization and reorganization with consideration for Arab-majority parts of the empire. But, World War I disrupted whatever trends were developing and replaced them with a new dynamic in which the Ottoman Empire was a territorial shell of its former self, and proved quite susceptible to replacement by a republic organized around the idea of a Turkish nation. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 solidified the political boundaries that later became the countries of the Middle East. At the same time a movement to recognize the sovereignty of colonized countries led to the creation of mandates based on the territories ruled by European countries, with the idea that they would develop toward independent status.

Many promises were left unfulfilled, however, as cultural communities such as the Kurds were left with no territory of their own. To this day, the Kurds are a “stateless nation”, with their territory spanning across 4 nation-states: Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran (see map, below). We cover the concept of a stateless nation and provide other examples in this chapter as part of a discussion on the national identities of the Middle East of today.