3 The Five Elements of Fiction

“We are all born storytellers.”

– Fernanda Santos

Learning Objectives

The learning objectives for this chapter are as follows:

- To develop a basic understanding of the five elements of fiction.

- To foster a deeper appreciation for literary techniques applied to nonfiction work.

I often begin a course of Narrative Journalism with the question: What “elements” must all stories have for them to be ’stories’? What follows is a cascade of student responses that touch on character, setting, meaning and theme, conflict and events and terms used to describe the plot or story arc. And indeed, all stories must be about someone or something, and this someone or something will exist in some sort of environment, whether that be a concrete or abstract place. And yes, all stories should have meaning, and meaning that we can connect with as human beings. Even with characters situated in a place, there must also be things happening (or deliberately not happening) to someone or something for any story to progress. The fifth element of fiction is more related to craft and technique rather than content, and while it is celebrated in fiction writing, it is equally useful in creative nonfiction—that element is point of view.

While Creative Writing scholars are not always in agreement about the elements of fiction, general consensus outlines five essential elements that feature in all stories: they are 1.) Theme, 2.) Character, 3.) Setting, 4.) Plot, and 5.) Point of View.

Theme:

As described at the beginning of this chapter, we read stories to see ourselves revealed in them, to find meaning in them through a character’s trials and tribulations. While much depends on the individual reader, a writer creates characters, places them in particular places, chooses a point of view (or more), and organizes events in a certain way in order to teach us something or show us something that means something. While theme often describes broad concepts like love or honor or vengeance or solidarity, most stories also carry with them a message, a more specific statement about the theme or themes. Without meaning, stories are forgettable. Meaning gives stories true life.

Character:

Character is perhaps the most important element of fiction, as things must happen to someone or something in order for a story to progress. Not only is this crucial for story development, but as human beings, we read stories and enjoy stories because we can see ourselves in them, often through the characters. In order to understand this element of “character,” and how we as narrative journalists can more deliberately craft our stories, there are a few keywords that should be defined further:

Protagonist:

The protagonist is your main character, your lead, the character the story revolves around. Think Harry Potter or Anne of Green Gables or Pee Wee Herman or the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Antagonist:

The antagonist is your ‘villain,’ the character who often creates the most strife and struggle for the protagonist. While nonfiction doesn’t always include characters that fulfill certain ‘roles,’ it is important to think about relationships between characters, particularly relationships between your story subject (your protagonist) and others, whether they be central or peripheral characters.

Round vs. Flat Characters

Round versus Flat are terms used to describe character development. Round characters are fully developed, ‘human’ characters, full of complexity and nuance. They have the capacity for the full range of human emotion, and they are capable of both right and wrong. Think Ted Lasso or Cersei Lannister from Game of Thrones. Flat characters are typically one-dimensional. They are stereotypes, essentially. Think Voldemort from Harry Potter, or Mr. Belding from Saved by the Bell.

Static vs. Dynamic Characters

Static versus Dynamic are also terms used to describe character development. Static characters are characters who do not experience any sort of change throughout the story. Dynamic characters do experience change, often profound change, and this can be physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual. While there is space for both static and dynamic characters in stories (based on what the characters represent within the story), readers connect better with dynamic characters.

Setting:

As important as characters are, characters are both influenced by and hold influence over the places they inhabit and visit. In addition, the sequence of events (discussed in the next element below) are inextricably linked to “place.” All that being said, “place” and “setting” deserve further description and definition:

Place:

When setting is concerned, there is a spectrum of both place and time. Place encompasses geographical location, of course, but also everything that plays a part of that mosaic. The people, the culture, the community, the politics, the weather, the physical landscape, the weather, the flora and fauna, all of it contributes to what a place is and how the characters interact with it. Think about a story taking place in the Arctic Circle versus a story on a remote desert island. Think about your hometown versus New York City or a small town out in rural Tennessee. Place matters for more reasons than simple geography.

Time:

Likewise, time must be defined on a spectrum. Time can mean literal time of day, the season, the era, and all of these deviations of time will impact the characters and the story monumentally. Think about stories set at night versus in the day, summertime stories versus other seasons, stories that take place during WWII versus science fiction stories of the future.

Plot:

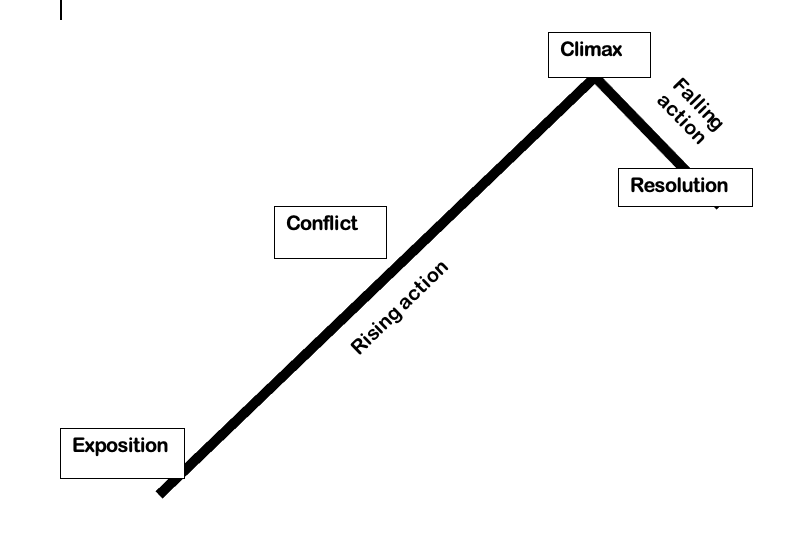

Plot (what I often refer to as narrative design) can be defined as the sequence of events in which the story plays out, but on a fundamental level, it encompasses much more than that, and in order to fully embrace the power of plot from the perspective of “craft”, we must explore those elements. The traditional western plot structure follows what is called the inverted checkmark.

The inverted pyramid plot structure follows the classic “hero quest,” where the protagonist experiences struggle and conflict as the action rises, then the story reaches its tipping point, or climax, and in the falling action the protagonist experiences some sort of change, whether physical, mental, spiritual, etc. Some of the key terms to be aware of are the following:

Exposition:

Exposition is all the stuff included at the beginning of a story to provide context. Characters might be introduced. The setting might be described. Some sort of tension might appear. There isn’t a lot of action in the exposition, but it sets everything up so that action can begin.

Rising Action:

The rising action is everything that happens leading up to the climax, including the conflict. This is when all of the tension builds, conflict rages, and we reach a breaking point in the story.

Conflict:

The conflict is often defined as the main struggle that the protagonist experiences. This could be physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, or a combination of these.

Climax:

The climax of the story is the turning point. This is when the conflict and tension reach their crescendo and typically the most important scene or event takes place. Typically, the story begins to conclude after the climax.

Falling Action:

The falling action is everything that occurs following the climax. It takes us out of the story and winds everything down.

Resolution:

The resolution is the conclusion of a story, typically focusing on some change that the protagonist has experienced.

While we can not invent events or plot points in a piece of nonfiction, we are in complete control of the narrative design and how those events are revealed to the audience. Techniques such as flashback, flash forward, and suspense are all extremely effective in narrative journalism.

Point of View:

Point of view is perhaps the unsung hero of literary devices. This element is inherent in any form of storytelling, and while it doesn’t shout out to us and demand our attention as an aspect of craft because of how natural it is, it impacts everything in terms of how we experience a story. Below are the different types of point of view and the impact they can have in a story:

First Person:

First person point of view takes the form of the first person pronoun “I,” “me,” “we.” This point of view is very compelling as it brings us intimately close to the narrator, and while there is often a question of the narrator’s reliability, first person is very engaging through its use of tone and voice.

Second Person:

Second person point of view takes the form of the second person pronoun “you.” This is the least commonly used point of view, though it has its use in “choose your own adventure” style stories. This point of view puts the reader directly into the story, but it can often feel inauthentic and contrived.

Third Person:

Third person point of view takes the form of the third person pronouns, “he,” “she,” “they.” This point of view is one of the most common, particularly in nonfiction, but it can be broken down further according to psychic distance from the characters (listed in order from most psychic distance to least).

- Objective: Objective 3rd person POV is fully removed from the thoughts and feelings of the characters. With 3rd person objective, we only hear words and see actions. This the traditional point of view for stage plays.

- Limited (Omniscient): Limited omniscient 3rd person POV delves into the thoughts and feelings of one character, often the protagonist. With this point of view, we get into the psyche of the character.

- Omniscient: Omniscient 3rd person POV delves into the thoughts and feelings of all of the characters. There is no psychic distance between the reader and the characters, and this point of view can be used to set up dramatic irony, where the characters don’t understand one another, while the reader has insight into what motivates and frustrates each character.

Media Attributions

- Inverted Checkmark Graphic © Ben Wielechowski is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

Flashback is a technique used in storytelling to leap back in time from the chronological progression of the story.

Flash forward is a technique used in storytelling to leap forward in time from the chronological progression of the story.

A literary technique used to create tension in a story by withholding crucial information or playing around with mood, setting, etc.

Psychic distance refers to the proximity the reader is to the characters’ psyches. The closer the psychic distance, the more the reader knows about internal thoughts, emotions, etc.