7 Plot

“Narrative is chronology: This happens, that happens, the other thing happens, and then something else happens. [….] Story is something else: taking select parts of a narrative, separating them from everything else, and arranging them so they have meaning. Meaning is intrinsic to storytelling.”

– Jon Franklin

Learning Objectives

The learning objectives for this chapter are as follows:

- To explore the relationship between the element of plot and the concept of “narrative design.”

- To better understand how genre impacts plot and structure and how narrative journalists can leverage this element of fiction across genres.

While plot is a very instructive and accessible term as far as literary elements are concerned, I prefer the term narrative design for narrative journalism, as it prioritizes craft over storyline. And, as mentioned in Chapter 3, we cannot manipulate the storyline when writing nonfiction. We cannot invent events and we cannot delete events. We cannot rearrange how events occurred in a piece of nonfiction (as this creates monumental ethical violations). We can, however, play around with how the story is revealed to our reader, and this is why the element of plot is such a crucial and effective tool in narrative journalism.

Often considered to be the “quintessential” text of narrative journalism, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood catalogs the murders of the Clutter family, a wealthy farming family located in a small town in Holcomb, Kansas, and while these stories of unnecessary violence were not new, the storytelling techniques Capote incorporated were rarely seen before in nonfiction. From dozens of hours of primary research, mainly interviews with the convicted murderers, Capote recreated the days leading up to, the night of the murders, and the weeks and months and years that followed including the manhunt, arrest, conviction, and eventual execution of the two convicted. Capote moves around in time, from before the murders, chronicling the movements of the Clutter family and the two would-be murderers, and then brings the stories together in a way that reads like fiction. The story is in and of itself “stranger than fiction,” but Capote manages something far greater than a front page news story with his mastery of narrative design.

Narrative Design:

Narrative design has everything to do with the structure of a story. Yes, plot is involved with what happens first, second, third, etc., and how all of the events impact and influence one another, but narrative design takes a step back from the story in order to fully consider the reader experience (and not just what the characters are doing). What arrangement of the narrative will most powerfully impact the audience, and how best can we communicate our angle? For the most effective narrative design, full consideration must be given to the reader and the reading experience. Let’s take a look at a student example to analyze just how narrative design can be used to affect that reader experience:

Example

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vy4NlpaH4KM

By: Jenna Elder

Jenna begins this mini-documentary focusing in on her protagonist as she completes a Covid check-in before attending practice. This is an expert narrative device, as we are immediately immersed. The next sequence in the film provides national context for the covid pandemic. Then the focus returns to the protagonist and her experience and perseverance through the pandemic. The design choices to include multiple interviews that contrast the protagonist’s experience only further emphasize the angle of the story.

Narrative Design and Genre:

In order to highlight the power of narrative design and the opportunities we have as journalists, let’s compare and contrast a few different genres: narrative journalism, news journalism, and scriptwriting/graphica. Each require a specific design or structure in order to adhere to the conventions of the genre. Because of these differences, it is important to dissect the design to see how each genre works on a structural level.

- Narrative Journalism relies heavily on the elements of fiction, and so, there is added attention to character, setting, plot, point of view, and of course, theme. See how these elements play out in the following example:

Example

By: Autumn Tashman

Autumn begins by with a short personal narrative, which engages us through the elements of character and point of view, as this piece is driven by first person narration. Autumn also explores this “alternate reality” of social media and the impact this “place” has on people who visit. The mix of personal narrative and interviews, complemented by important secondary research, creates for a thorough and compelling expose about the effects of social media.

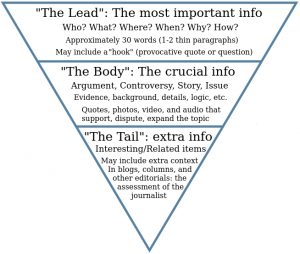

- Traditional Journalism conversely, follows a very specific form. The structure must follow the inverted pyramid, which provides the entire story in the headline and lede of the article.

The inverted pyramid structure typical of news journalism. The lede should answer the who, what, where, when, how, and why. This plot structure relies on revealing the most information possible in the least amount of time, prioritizing the information rather than the story. Narrative journalism, conversely, does almost the exact opposite: story over information. See this student example by Autumn Tashman, one that focuses on the same content matter as the previous example, but look at how formulaic the structure is, from the headline, to the subheadline, to the lede (all telling the full story), then into the body of detail within the story, and finally the tail:

Example

The Effect Upward Comparisons Have on Social Media Users

Comparisons amongst users on social media who display the highlights of their lives creates damaging effects on users.

(Image would usually be featured in this location with caption)

Autumn Tashman

When users log onto their social media platforms, they face comparing themselvesーbased on human nature for self-evaluationーwith people who showcase the highlights of their lives. This poses risk for users to feel worse about themselves and lead to depression, low self-esteem, and anxiety.

The Theory of Social Comparison that has been proposed by psychologist Leon Festinger states that it is “the proposition that people evaluate their abilities and attitudes in relation to those of others in a process that plays a significant role in self-image and subjective well-being” according to the APA Dictionary. It is also said that the three types of comparisons are upward, downward, and lateral, where upward comparisons are often seen in social media when people compare themselves with someone perceived to be better than him or her based on what this person showcases on their pages.

According to a study published in 2016 where 881 female college students were evaluated, it was found that “the more time teens spent on social media, the more they compared their bodies with those of their friends. Consequently, they felt more negative about their bodies.” Similarly, a study published in 2019 that investigated the effect “Instagram vs Reality” images had on 305 women found that body dissatisfaction increased when looking at the “ideal” images. While social media may not be to blame for human nature and their unavoidable nature to compare oneself with others for self-evaluation, what social media does is exacerbate this dilemma and create expectations for themselves where the baseline of these expectations is skewed to attract others.

The apps TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook are recommended for people ages 12 and up. For young adolescents, the ages of 12 to 13 are the years where body dysmorphia is first detected, according to a Help Guide article. It’s also said in this article that a symptom for body dysmorphia is comparing oneself negatively to others, and by the Theory of Social Comparison, humans have this sort of inevitability to take part in evaluating their own worth by comparing themselves with others, and social media platforms are just one place where this can be achieved. More specifically, well over the majority of people who act as the basis of comparison have been edited in a way that would make themselves look better online, through the photoshop app Facetune (71% of people say they won’t post a picture online without somehow touching it up). These 12-13 year old children have access to these types of photos that are intended to be appealing, which can lead to upward comparisons which in turn lead to low self-esteem and even symptoms of depression.

In a TedTalk, Bea Arthur, founder and CEO of The Difference, a company that provides on-demand access to therapy, addressed the possible effects that Facebook has on people. She says, “Facebook started out as a way to keep up with people that you like, but it’s slowly turned into a way to keep up with people that you now kind of resent.” Because people have a tendency to compare themselves to whom they are seeing online (that this friend just got married, or that friend just landed a new job at a Fortune 500 company for example), it creates this negative space where people begin to downplay their own successes based on the ones people choose to showcase online.

Anthropologist Bob Deutsch believes that “The very nature of [social media] causes all of us to be fake,” and he supports this claim by saying “…With the right filter and snappy status update can project an image of a life far better than the one we authentically experience.” Jessica Stillman agrees with Deutsch’s verdict, and backs up her claim that “The more miserable you are, the happier your social media posts” by using a Twitter thread showing that social media harbors people’s dark sides in life. For example, one woman posted a joyful-looking picture of her holding her smiling baby with the caption, “This photo is of me and my daughter (now almost 9) as a baby. I hadn’t slept in months and had RAGING postpartum anxiety. I loved her but mostly wanted to run away. I was tired and angry and scared all the time.” What’s seen on social media is only what people want others to see, and in reality, viewers are missing out on half, if not more, of the full story.

Doctor Steve Rose reported that “social media use activates the same reward centers in the brain triggered by addictions to chemical compounds.” Every “like” that a person gets triggers the brain’s reward center, creating this addictive effect to receive likes, and as a result, people will do what it takes to feel the reward of earning more likes on their posts. For many, this involves using photoshop, retaking a selfie dozens of times, finding the perfect lighting and angle for a pose, and more. While it’s essentially impossible to prevent comparisons among users, understanding that what is advertised on social media most likely isn’t the real-deal is a first step in canceling out the negative effects that may come with self-evaluation through others.

Sources:

How social media is increasing a person’s exposure to body shaming and body image (indiatimes.com)

Rising dysmorphia among adolescents : A cause for concern (nih.gov)

Statistics — Megan Meier Foundation

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) – HelpGuide.org

Comparison culture: impact of Instagram on our self-esteem (stylist.co.uk)

Social Comparison Therapy in Social Media | Newport Academy

‘I Was Obsessed With Facetune’: 71% Of People Won’t Post A Picture Online Without Photoshopping It – That Needs To Change | Grazia (graziadaily.co.uk)

Gender differences in Mental Health – RAMH

Why Everyone and Everything on Social Media Is Fake (entrepreneur.com)

The More Miserable You Are, the Happier Your Social Media Posts, and This Twitter Thread Proves It | Inc.com

Why We Are Addicted To Social Media: The Psychology of Likes | Steve Rose, PhD social comparison theory – APA Dictionary of Psychology

- Scriptwriting and Graphica doesn’t technically fall within the genre of narrative journalism, but it can be extremely insightful in how we negotiate our narrative design. Both forms are very character and scene driven, and so we can learn more about narrative design through exploring this unique format. This format is also more directly connected to fiction than are some of the other formats, and that liberty in craft can also be instructive. When compared to documentary, which is a classic form of narrative journalism, scriptwriting and graphica are more impressionistic, and by this I mean scriptwriters take an event that has happened (rather than while it is happening) and present a version of the event or issue with some form of hindsight. This taps into our sense of meaning, and so as writers, we have to think more deeply about how scene and character can convey meaning outside of a strict chronology of events. Let’s take a look at the following example by Autumn Tashman to see how she tackles the same subject matter (effects of social media) through this new format:

Student Example

Autumn Tashman

Scene 1:

Three best friends, Alyssa, Jasmine, and Alex are hanging out at a sleepover get-together, scrolling through their TikTok feeds before getting ready for bed. Alyssa stumbles across a trending TikTok dance that she’s been wanting to do for several days.

Alyssa: You guys have to do this TikTok dance with me! We could totally become famous off of this! We literally just have to stand in one spot and jump around a bit. Then BOOM! People will love us!

Jasmine: Eh, I’ll pass on this one. You two go ahead.

Jasmine gives a smile of encouragement to her friends, Alyssa and Alex.

Alex: All right, fine. But Alyssa, if this blows up, I’ll hate you forever; you know how bad I am at dancing!

Alyssa: Yeah yeah yeah. Come on!

Alyssa teaches Alex the dance, and they take a couple of tries to perfect it to the best of their abilities. Once they are satisfied, Alyssa uploads it onto her page.

Jasmine: You guys look great in this! You know Alyssa, even though you only have 200 followers, I think this video could be a real hit.

Alyssa: Thanks Jasmine! I hope you’re right!

Scene 2:

The next morning, the three girls are asleep, but Alex is rudely awakened by the sound of someone’s phone constantly buzzing. She comes to realize that Alyssa’s is the one that is making all the rukkus.

Alex: Hey, hey, Alyssa, wake up!

Alyssa: Why, what’s wrong?

Alex: Your phone has been dinging for the past 30 minutes, it’s driving me crazy!

Alyssa: What?! No way, it must be the video we uploaded, let’s check it out.

Alyssa checks her phone to realize that the video of Alex and her dancing has 400k views and 30k likes. Alex pulls out her own phone to look at the uploaded video alongside Alyssa.

Jasmine: Wow, the video actually blew up! I was kinda half-joking when I said that your video would get famous cause I feel like that never happens, but look at that, you go girls! What are the comments saying about it?

Alex: Ummmm… You might not want to look at them Alyssa.

Alyssa: (Beginning to tear up) Oh my god. These comments are awful. How could anybody even think to say something so rude?

Jasmine: What are they saying?

Alex: I mean, a lot of them are positive, but there are a good amount of them that are comparing the two of us. Also, take a look at this one.

Alex hands Jasmine her phone, and Jasmine begins to read one of the comments.

Jasmine: “Why is the girl on the right shaped like that? I don’t know what I’d do if I looked like her”… Alyssa, I’m so so sorry. The people commenting these things are so insecure about themselves that they find other people to hate on to make themselves feel better.

Alyssa: Maybe, but that comment alone had over 400 likes. At this point, I don’t even know if people are caught up in their own insecurities, or if they genuinely think I’m unattractive. I never should have posted this stupid video.

Alex: Alyssa, don’t think like that! You look amazing in the video, and people just live for drama online. I know it’s easier said than done, but try not to take these comments to heart.

Alyssa: Yeah… right.

Scene 3:

2 MONTHS LATER

The three best friends facetime each other for Christmas day. While they spend time apart, they are all curious to know what they all got under their trees.

Alex: Merry Christmas girlies! What did you all end up getting under your trees?

Jasmine: Just the usual! some clothes, makeup, and nail polish. But I also got this super cute new pair of shoes! What about you, Alyssa?

Alyssa: Nice! I’ve been wanting this new pair of shoes, but I didn’t have room to ask for them on my list. I ended up getting this super cool high-end jump rope, some protein powder, a set of weights, and some other little things. I’m so excited to try them out.

Alex: That all sounds great, but Alyssa, it never seemed like you were into the whole sporty-exercise kinda thing. Are you doing this because of what people said on that one video from a while back?

Alyssa: Honestly, that has a lot to do with it. I think it’s easier said than done, trying to ignore the hate, and a lot of those comments really got to me. But man, do I hate today’s standards.

Jasmine: You could say that again. People expect so much from us, and when we don’t fit what people like to see, we get hate. UGH! What a twisted reality.

Alyssa: Yeah, tell me about it.

Media Attributions

- Inverted-pyramid-in-comprehensive-form © Christopher Schwartz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Genre is a term used to define a category or type of creative expression sharing similar style, form, or subject matter.

Stage direction refers to the descriptive content that helps the audience (and performers) visualize the stage setting and arrangement of characters.