Michael D. Jones; Mark K. McBeth; and Elizabeth A Shanahan

Michael D. Jones*, University of Tennessee

Mark K. McBeth, Idaho State University

Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Montana State University

*Corresponding author: mjone239@utk.edu

To cite chapter: Jones, Michael D., Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2022. “A Brief Introduction to the Narrative Policy Framework”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 1-12. DOI: 10.15788/npf1

A long history of literature describes how stories are central to how humans understand and communicate about the world around them (e.g., Polkinghorne, 1988). The NPF applies these discoveries to the policy process, whereby narratives are meaning-making tools used to capture attention and influence policy outcomes (Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2015). Conceived at the Portneuf School of Narrative (McBeth, 2014) in the early part of the century (e.g., McBeth and Shanahan, 2004) and formally named in 2010 (Jones & McBeth, 2010), the Narrative Policy Framework’s (NPF) initial purpose was to scientifically understand the relationship between narratives and the policy process (Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2011). Since its seminal naming, the NPF’s charter has expanded to non-scientific approaches (Gray & Jones, 2015; Jones and Radaelli, 2015), to science and policy communication (Crow and Jones, 2018; Guenther and Shanahan, 2020; Jones & Crow, 2017; Lybecker, McBeth, Kusko, 2013; Raile et al., 2022), as well as proclaiming normative commitments to both science and democracy (Jones & McBeth, 2020; Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2015). Recently, guideline publications have also been produced that provide detailed instructions about how to conduct NPF research (Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2018; Jones, McBeth, Shanahan, Smith-Walter, and Song, 2022). Along the way several summary pieces have chronicled the NPF’s development (Jones, Shanahan, and McBeth, 2014; Jones, 2018; McBeth, Jones, and Shanahan, 2014; Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2015; Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Radaelli, 2018). Two of these NPF assessments were part of larger collections of NPF studies, including the 2014 edited volume The Science of Stories (Jones, Shanahan, and McBeth, 2014) and a special NPF symposium issue featured in the Policy Studies Journal (Jones, 2018). On par with NPF collections emerging every four years, here we offer a third collection of NPF studies that represent some of the best NPF studies to date. This introductory chapter provides a brief overview of the NPF and is followed by a short introduction to the contents of this volume.

The Narrative Policy Framework

Heuristically drawing on the model, theory, and framework distinctions of Elinor Ostrom (e.g., 2011; Schlager, 1999; 2007), we describe the NPF as a framework because the NPF is a way to identify, organize, and understand concepts and their relationships to other concepts within the policy process. For example, an obvious concept with which the NPF is concerned is policy narratives; in turn, an obvious relationship of interest for the NPF is that between policy narratives and public policy. Of course, there are many other policy relevant concepts that the NPF incorporates (e.g., focusing events, coalitions, and institutions), but the gist of the NPF as a policy process framework is that it organizes the relationships among those theoretical concepts toward the goal of helping researchers and policymakers develop expectations about public policy. Working from the framework heuristic, we further draw on Imre Lakatos’ (1970) understanding of scientific research programs, which are understood to be founded upon unstated assumptions that are rarely tested. From said assumptions, researchers are able to derive testable hypotheses. Like Lakatos suggests, NPF assumptions are usually untested1; unlike most policy process approaches, the NPF explicitly identifies her assumptions. The following is a summary of NPF assumptions (see also Jones, 2018; Shanahan et at., 2018).

Assumptions

- Social construction of policy realities. There is a reality independent of our ability to perceive it. However, the NPF assumes that it is the perceptions and interpretations of that reality (i.e., social construction) that matters for public policy.

- Bounded relativity. As people interpret the world around them, the meanings with which they imbue various objects, concepts, and relationships can vary to create different policy realities. However, the possible interpretations are not limitless, nor are they random. The NPF assumes that the relativity of meaning-making is bound by the systematized ways people regularly use to make sense of the world around them, such as their identities and belief systems or the strategies they use to organize concepts, objects and relationships to instrumentally engage the world.

- Narrative generalizability. In contrast to narrative literature in public policy that precedes the NPF (e.g., Fischer, 2003), the NPF adopts a structuralist approach to narrative (e.g., Shenhav, 2015), where narratives contain identifiable and measurable elements (e.g., characters, setting). As such, it is appropriate to categorize, count, and perform statistical operations on policy narratives across policy contexts.

- Three levels of analysis. The NPF identifies three levels of analysis. The micro-level focuses on the narratives of individuals. The meso-level captures group and coalition level narratives.The macro-level focuses on the broad narratives of cultures and institutions that provide ideational boundaries for micro- and meso-level narratives. While often examined as discrete levels, the NPF assumes interaction between levels of analysis.

- Homo narrans. From an amalgamation of theorizing and research findings across diverse academic fields, the NPF identifies ten postulates (Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Radaelli, 2018, p.180-183) that culminate in the homo narrans assumption, which states that narrative is the primary means by which people process information, communicate, and reason.

Policy Narrative Components and Elements

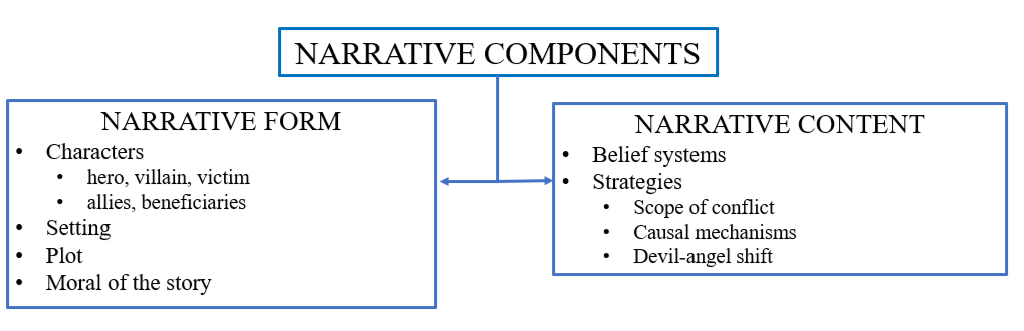

To elucidate narrative generalizability (assumption three above), the NPF draws on a distinction often drawn by narratologists (see Jones and McBeth, 2010 pp. 331-339) to disaggregate narratives into two component categories: narrative form and narrative content. Narrative form captures the concepts that are theorized to be generalizable across time and space. That is, these concepts can be found within policy narratives, regardless of context. Narrative content refers to more specific—but potentially generalizable—concepts and relationships found within policy narratives, specifically belief systems and narrative strategies.

Figure 1. Narrative Components

Narrative Form

The NPF assumes that policy narratives are objects in the world that can be further disaggregated into constituent concepts, termed narrative elements. Although not strictly limited to four, the NPF’s most common elements are as follows:

- The setting is where the action takes place. It is the narrated context of the policy narrative and contains policy consequential information that the narrator determines to be relevant. Such information includes but is not limited to geography, demographics, legal rules and structures, evidence, and any other policy consequential information deemed relevant by the narrator. Facets of the setting can be either taken-for-granted or contested. In all settings, some information will be foregrounded, other information will be backgrounded, and some information will be left out altogether.

- Characters are the actors portrayed in a policy narrative. Typically, the NPF has defined these characters as victims who are harmed or potentially harmed, villains responsible for the harm, and heroes who bring promise of ending the harm. Other characters (e.g., beneficiaries, allies, and others), though less common in NPF research, are also possible to operationalize.

- Plots situate the characters within the setting and establish relationships between different characters, as well as facets of the setting.

- The moral is the point of the narrative. Typically, in a policy narrative the moral is either a policy solution or a call to action.

Narrative Content

While NPF theorizing holds that elements of narrative form are more easily replicated and generalized, narrative content has been notoriously difficult to generalize. It has been convincingly argued2 that the interactions between the narrator, the narrative, the context in which it is delivered, and the individual receiving the narrative leads to a sui generis experience—a one of a kind instance that defies replicability. In simpler terms, a narrative about Swiss Child and Adult Protection Authorities (Kuenzler, 2021) is different than COVID-19 policy response narratives (Mintrom, Rublee, and Bonotti, 2021), and when, where, and how the story is told changes its meaning, even if only ever so slightly. Within the NPF, we refer to this phenomenon as the problem of narrative relativity (Jones, McBeth, and Shanahan, 2014). While the NPF recognizes that narrative content and the experience of it has considerable variation, we reject that this variation is random (which a sui generis position on narrative would have to argue). This is the NPF’s second assumption of bounded relativity; anyone who has dealt with actual human beings would quickly recognize that people have very entrenched ways of making sense of the world around them. Thus, to generalize narrative content means identifying those systems, as they occur across populations of interest, within specific contexts. The NPF does not claim to eradicate this formidable problem of narrative relativity, but it does offer two approaches that moderate the problem by capturing the systematic boundedness of human rationality.

Belief systems are the NPF’s first approach to moderating the problem of narrative relativity that allow for reliably generalizing the meanings of specific narrative content. When people come into contact with a narrative (or, any information for that matter), they do so with the baggage of their experiences and the systemized ways that they already possess for making sense of those experiences. Many of these systemized ways of meaning-making are derivative of the various groups with which individuals identify. Thankfully, researchers from many academic disciplines have devoted considerable attention to figuring out what these belief systems are and how they work. An obvious choice within the United States (US) context is political ideology. Due to the two-party system within the US many policy issues, once popularized, flatten out into a single dimension of left-right, with liberals and conservatives occupying their side of the respective dimension. So, for example, if conservatives and liberals are presented with an intendedly “neutral” policy narrative about the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations in late 2020, we would find that conservatives view the vaccines negatively, while liberals view them positively (Jiang et al, 2021). Ideology works similarly for many issues and the concepts, objects, and relationships related to those issues. However, not every issue is a US-based ideological issue, and finding the appropriate and theoretically-based belief system for the issue and its context is key. To that end, NPF researchers have found many belief systems useful within varied contexts, including cultural theory (Jorgensen, Song, and Jones, 2018) and Lakoff’s moral politics theory (Knackmuhs, Farmer, and Knapp, 2020), among others.

Strategies are the second way to moderate the problem of narrative relativity. Similar to belief systems, people regularly manipulate narratives to suit their needs. That is, we strategically construct narrative to persuade, to elicit sympathy, to entertain, and so on. Within these broader narrative goals are systematized permutations that are deployed by narrators, despite narrative contexts, thereby allowing NPF researchers to generalize. Common strategies examined within the NPF include scope of conflict (e.g., Stephan, 2020), the devil/angel shift (e.g., Merry, 2019), and causal mechanisms (Shanahan, Adams, Jones, and McBeth, 2014).

Narrative Form and Content

Existing NPF orthodoxy defines policy narratives as minimally consisting of at least one character and some reference to the policy or issue (Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Lane, 2013). Above and beyond this minimal definition, NPF researchers frequently assess policy narratives in terms of their narrativity (McBeth, Shanahan, Anderson, and Rose, 2012), where the total number of elements (characters, plot, beliefs, etc.) are summed to determine how “much” narrative is actually present in a given text (e.g., Boscarino, 2020; Huda, 2018).

It is from the above concepts and their posited relationships with other concepts within the framework, that NPF hypotheses and propositions are derived and tested. It is beyond the scope of this introductory overview chapter to cover these hypotheses and propositions in depth. However, interested readers can find collections of NPF hypotheses and discussions of relevant findings within many of the overviews of the framework (Jones, Shanahan, and McBeth, 2014; Jones, 2018; McBeth, Jones, and Shanahan, 2014; Shanahan, Jones, and McBeth, 2015; Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, and Radaelli, 2018).

The Contents of this Volume

Now that you are familiar with the basics of the NPF, the following discussion provides a brief summary of each of the contributions to the edited volume. Chapters 2 and 3 (Gupta et al., 2022; Wolton, Crow, and Heikkila, 2022) represent advanced methods used in the application of the NPF. Chapters 4 and 5 (Lybecker, McBeth, and Sargent, 2022; Peterson, Zanocco, and Smith-Walter, 2022) are micro-level NPF studies, and chapters 6 and 7 (Colville and Merry, 2022; Smith-Walter, Fritz, and O’Doherty, 2022) are more focused on the meso-level. Finally, chapters 8 and 9 (Baldoli and Radaelli, 2022; Wolters, Jones, and Duvall, 2022) represent unorthodox approaches using the NPF. Below is a brief summary of each chapter.

Chapter 2, “Discourse Network Analysis of Nuclear Narratives”, authored by Kuhika Gupta, Joseph Ripberger, Andrew Fox, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Carol Silva, (Gupta et al., 2022) combines the NPF with Discourse Network Analysis (DNA) (Leifeld, 2020) to examine nuclear narratives. In doing so the authors seek to merge the two approaches toward the end of producing a general approach to studying policy coalitions. Their study examines the policy narratives of support and opposition to the use of nuclear energy across Twitter, arguing that the NPF and DNA combined provide unique observations that would not be visible to other types of narrative analysis, specifically the potential fissures within coalitions that could threaten coalition stability.

“Stepping Forward: Towards a More Systematic NPF with Automation”, Chapter 3 by Laura P. Wolton, Deserai A. Crow, and Tanya Heikkila (Wolton et al, 2022) advances the NPF toward the goal of automated coding. The research presented in this chapter uses semi-automated text analysis to examine the relationship between narrative structural elements and the broader frames that encase them. Over 5,000 state and local news articles related to hydraulic fracturing of oil and gas are examined. Their findings show that, depending on the frame, there is substantial variation in how characters and policy solutions are portrayed.

Chapter 4, “ Agreement and Trust: In Narratives or Narrators?”, Donna L. Lybecker, Mark K. McBeth, and Jessica M. Sargent (2022), use an online experimental design to examine the role of narrators in shaping respondent trust related to climate change. Leveraging two narratives, one pro and the other anti-climate change, where the narrators are designed to pre-appeal to respondents based on associations with key cultural indicators, this research finds that who is narrating and how that narrator aligns with the priors of individuals plays a substantial role in how persuasive narratives are. The study contributes to the NPF by providing data on the role of the narrator versus the role of narratives in contentious policy issues like climate change.

The fifth chapter of this edited volume, “Lost in Translation: Narrative Salience of Fear > Hope in Prevention of COVID-19”, is written by Holly L. Peterson, Chad Zanocco, and Aaron Smith-Walter (Peterson et al, 2022). Leveraging a survey experiment, the research presented in this chapter deploys short policy-image-like narratives to test the salience of problem and solution COVID-19 narratives. Their findings show that fear is more salient than hope and that neither narrative impacted the likelihood that respondents would abide by CDC COVID-19 guidelines. Consistent with past research (Peterson, 2012), their findings also show that Democrats are more likely to show preferences for fear stories. This study points to potential limitations of narrative persuasion.

“Speaking from Experience: Medicaid Consumers as Policy Storytellers”, Chapter 6, by Kathleen Colville and Melissa K. Merry examines policy narratives associated with the USA state of Kentucky’s proposed 2016 Medicaid reforms that were eventually blocked in federal court (Colville and Merry, 2022). Analyzing the policy narratives contained within a random sample of 1100 public comments submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, this research finds that most of the comments qualified as narratives (vs. non-narratives) and that they formed distinct storylines. One of the contributions of this chapter for NPF research is that it focuses on bottom-up narrative construction and also illuminates the potential importance of public comments as sources of policy narrative data.

Chapter 7, “Sanctuary Cities, Focusing Events, and the Solidarity Shift: A Standard Measurement of the Prevalence of Victims for the Narrative Policy Framework,” by Aaron Smith-Walter, Emily Fritz, and Shannon O’Doherty, examines the phenomenon where cities actively pushed back against US deportation policies (Smith-Walter et al., 2022). Termed “Sanctuary Cities”, this research uses NPF guided content analysis to analyze 164 public consumption documents deployed by interest groups involved in the sanctuary city policy debate occurring between 2010 and 2017 within the United States. Findings in this chapter show significant differences in advocate and opponent policy narratives and also reveal a new NPF theoretical concept, termed the solidarity shift. The authors argue that the solidarity shift contributes to the NPF by allowing researchers to better capture the prevalence of victims within policy narratives.

The eighth chapter of this second collection of NPF studies, titled “A Nonviolent Narrative for European Integration”, by Roberto Baldoli and Claudio M. Radaelli (Baldoli and Radaelli, 2022), takes the NPF to rarely traversed territory by applying the framework toward an explicitly normative goal. The authors of this chapter ask the question of whether or not the NPF can be used to craft a narrative of European integration to counter populist narratives. To that end, Baldoli and Radaelli explore the foundations of existing populist narratives, present a possible alternative of European integration, and then compare NPF structural elements of each. They answer yes. The NPF can be usefully applied to these kinds of normative goals, which is to our understanding a novel use of the NPF.

Chapter nine, “A Narrative Policy Framework Solution to Understanding Climate Change Framing Research” by Erika Wolters, Michael D. Jones, and Kathryn Duvall (Wolters et al., 2022) also applies the NPF in a novel way. Rather than a traditional NPF study describing individual, group, or institutional policy narratives, or how they are deployed , this chapter leverages the NPF to heuristically organize climate change framing literature and research. Focusing on climate change mitigation and adaptation framing research, the authors argue that climate change framing findings are both incredibly large in number and also incredibly disorganized, to the point of being unmanageable. They then proceed to organize climate change research findings along NPF structural dimensions–or, rather, in story form. The authors argue that by reorganizing the literature in this way, the NPF improves the likelihood that climate change framing research will be used by fellow researchers and also makes it easier to communicate scientific findings to the public and important decision makers.

Chapter 10, “Innovations and Future Directions for the Narrative Policy Framework” (Shanahan, McBeth, and Jones, 2022) highlights the innovations found in these chapters. This chapter highlights this volume’s new applications of traditional NPF concepts, introduction of new NPF concepts, new methods used in the NPF context, and new applications of the NPF. We reflect on how the compilation of these works in this volume is a step toward representing the complexities of narrative and policy processes as well as the normative dimensions of these inquiries.

Conclusion

In a period of history where public policy making increasingly revolves around competing narratives, the NPF will no doubt play a crucial role in helping us understand how and why narratives are produced and how and why certain narratives are preferred over others and by whom. Thus, we believe that independent of the specific policy issues covered in this volume, the NPF’s relevance is tied specifically to its theoretical utility. This volume demonstrates and showcases that utility. The chapters cover a host of issues (climate change, medical coverage, European integration, hydraulic fracturing, nuclear energy, COVID-19, and sanctuary cities) and policy narrative concepts (e.g., characters, narrator, solidarity shift). Given the breadth of topics and the various theoretical aspects of the NPF that are covered in each of the chapters, we expect most policy scholars will find something of value within the volume, whether you are a long-time reader of the NPF or someone just becoming acquainted with the framework. But you need not take our word for it. The volume is open access and free to all. All that is required is your time.

References

Baldoli, Roberto and Claudio M. Radaelli. 2022. “A Nonviolent Narrative for European Integration”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 197-221. doi.org/10.15788/npf8

Boscarino, Jessica E. 2020. “Constructing Visual Policy Narratives in New Media: The Case of the Dakota Access Pipeline”. Information, Communication & Society, 1– 17.

Colville, Kathleen and Melissa K. Merry. 2022. “Speaking from Experience: Medicaid Consumers as Policy Storytellers”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 138-165. doi.org/10.15788/npf6

Crow, Deserai and Michael D. Jones. 2018. “Narratives as Tools for Influencing Policy Change,” Policy and Politics 46(2), 217-234.

Fischer, Frank. 2003. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gray, Gary and Michael D. Jones. 2016. “A Qualitative Narrative Policy Framework?: Examining the Policy Narratives of US Campaign Finance Reform.” Public Policy and Administration 31(3), 193-220: DOI: doi.org/10.1177/0952076715623356

Guenther, Sara K., and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2020. “Communicating Risk in Human-Wildlife Interactions: How Stories and Images Move Minds.” PLoS one 15(12): e0244440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244440

Gupta, Kuhika, Joseph Ripberger, Andrew Fox, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Carol Silva. 2022. “Discourse Network Analysis of Nuclear Narratives”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 13-39. doi.org/10.15788/npf2

Huda, Juhi. 2018. “An Examination of Policy Narratives in Agricultural Biotechnology Policy in India”. World Affairs 181(1): doi.org/10.1177/ 0043820018783046

Jiang, Xiaoya, Min-Hsin Su, Juwon Hwang, Ruixue Lian, Markus Brauer, Sunghak Kim, and Dhavan Shah. 2021. “Polarization Over Vaccination: Ideological Differences in Twitter Expression About COVID-19 Vaccine Favorability and Specific Hesitancy Concerns.” Social Media+Society 7(3): 20563051211048413.

Jones, Michael D. 2018. “Advances in the Narrative Policy Framework?: Insights from a Potentially Unreliable Narrator.” Policy Studies Journal 46(4), 724-746.

Jones, Michael D., and Deserai Crow. 2017. “How Can We Use the ‘Science of Stories’ to Produce Persuasive Scientific Stories?” Palgrave Communications. 3(1), 1-9.

Jones, Michael D. and Mark K. McBeth. 2010. “A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to Be Wrong?” Policy Studies Journal 38 (2), 329-353. DOI: doi.org.10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x

Jones, Michael D., and Mark K. McBeth. 2020. “Narrative in the Time of Trump: Is the Narrative Policy Framework Good Enough to be Relevant?” Administrative Theory & Praxis 42(2), 91-110.

Jones, Michael D. and Claudio M. Radaelli. 2015. “The Narrative Policy Framework: Child or Monster?” Critical Policy Studies 9 (3), 339-355. DOI: 10.1080/19460171.2015.1053959

Jones, Michael D., Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2014. “Introducing the Narrative Policy Framework.” In The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, edited by Michael D. Jones, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, and Mark K. McBeth. New York: Palgrave, 1-25.

Jones, Michael D., Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth Shanahan, Aaron Smith-Walter, and Geoboo Song. 2022. “Conducting Narrative Policy Framework Research: From Theory to Methods” in Methods of the Policy Process, Christopher M. Weible and Samuel Workman (eds), Routledge, 137-180.

Jorgensen, Paul D., Geoboo Song, and Michael D. Jones. 2018. “Public Support for Campaign Finance Reform: The Role of Policy Narratives, Cultural Predispositions, and Political Knowledge in Collective Policy Preference Formation. Social Science Quarterly 99(1), 216– 230: DOI:10.1111/ ssqu.12357

Knackmuhs, Eric, James Farmer, and Doug Knapp. 2020.” The Interaction of Policy Narratives, Moral Politics, and Criminal Justice Policy Beliefs”. Politics & Policy 48(2), 288– 313. DOI:10.1111/ polp.12343

Kuenzler, Johanna. 2021. “From Zero to Villain: Applying Narrative Analysis in Research on Organizational Reputation.” European Policy Analysis 7(S2), 405-424.

Lakatos, Imre. 1970. “Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes.” In Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, ed. Imre Lakatos, and Alan Musgrave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 170–96.

Leifeld, Philip. 2020. “Policy Debates and Discourse Network Analysis: A Research Agenda”. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.3249

Lybecker, Donna L., Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth Kusko. 2013. “Trash or Treasure: Recycling Narratives and Reducing Political Polarization.” Environmental Politics 22(2), 312-332. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2012.692935

Lybecker, Donna L., Mark K. McBeth, and Jessica M. Sargent. 2022. “Agreement and Trust: In Narratives or Narrators?”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 91-115. doi.org/10.15788/npf4

McBeth, Mark .K, Michael .D Jones, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan, 2014. ‘Preface: The Portneuf school of narrative. The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework in Public Policy Analysis.In The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, edited by Michael D. Jones, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, and Mark K. McBeth. New York: Palgrave, xiii-xviii.

McBeth, Mark K., Michael D. Jones, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2014. “The Narrative Policy Framework.” In The Theories of the Policy Process, 3rd Ed., edited by Paul A. Sabatier and Christopher M. Weible. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 225-266.

McBeth, Mark K. and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2004. “Public Opinion for Sale: The Role of Policy Marketers in Greater Yellowstone Policy Conflict.” Policy Sciences 37(3): 319-338. DOI: 10.1007/s11077-005-8876-4

Merry, Melissa .2019. “Angels Versus Devils: The Portrayal of Characters in the Gun Policy Debate”. Policy Studies Journal 47(4), 882– 904.

Mintrom, Michael, Maria Rost Rublee, Matteo Bonotti, and Steven T. Zech. 2021. “Policy Narratives, Localisation, and Public Justification: Responses to COVID-19.” Journal of European Public Policy 28(8), 1219-1237.

Ostrom, Elinor. 2011. “Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 39(1), 7-27.

Peterson, Holly L. 2021. “Narrative Policy Images: Intersecting Narrative & Attention in Presidential Stories about the Environment.” Policy Studies Journal, earlyview: https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12447.

Peterson, Holly L., Chad Zanocco, and Aaron Smith-Walter. 2022. “Lost in Translation: Narrative Salience of Fear>Hope in Prevention of COVID-19”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 116-137. doi.org/10.15788/npf5

Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1988. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: Suny Press.

Raile, Eric D., Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Richard C. Ready, Jamie McEvoy, Clemente Izurieta, Ann Marie Reinhold, Geoffrey C. Poole, Nicolas T. Bergmann & Henry King. 2022, “Narrative Risk Communication as a LinguaFranca for Environmental Hazard Preparation”, Environmental Communication 16:1, 108-124, DOI: 10.1080/17524032.2021.1966818

Schlager, Edella. 1999. “A Comparison of Frameworks, Theories, and Models of Policy Processes.”In Theories of the Policy Process, ed. Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 233–60.

Schlager, Edella 2007. “A Comparison of Frameworks, Theories, and Models of Policy Processes.” In Theories of the Policy Process, ed. Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 293–320.

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Mark K. McBeth, and Michael D. Jones. 2022. “Innovations and Future Directions for the Narrative Policy Framework”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 243-249; doi.org/10.15788/npf10

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. 2011. “Policy Narratives and Policy Processes.” Policy Studies Journal 39(3), 535-561. DOI: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00420.x

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Ross Lane. 2013. “An Angel on the Wind: How Heroic Policy Narrative Shape Policy Realities.” Policy Studies Journal 41(3), 453-483: https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12025

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Stephanie M. Adams, Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. 2014. “The Blame Game: Narrative Persuasiveness of the Intentional Causal Mechanism.” Michael D. Jones, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, and Mark K. McBeth, eds. The Science of Stories: Applications of Narrative Policy Framework: New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 69-88.

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. 2015. “Narrative Policy Framework.” Melvin Dubnick and Domonic Bearfield, eds. The Encyclopedia of Public Administration and Public Policy, 3rd Edition. New York, New York: Taylor and Francis. :http://www.crcnetbase.com/doi/10.1081/E-EPAP3-120053656

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. 2018. “How to Conduct a Narrative Policy Framework Study.” Social Science Journal 55(3): 332-345: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.12.002

Shanahan, Elizabeth, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth and Claudio M. Radaelli, 2017. “The Narrative Policy Framework”, in Theories of the Policy Process, 4th Edition, Chris Weible & Paul Sabatier (ed). Westview Press, 173-213.

Shenhav, Shaul R. 2015. Analyzing Social Narratives. New York, New York: Routledge.

Smith-Walter, Aaron, Emily Fritz, and Shannon O’Doherty. 2022. “Sanctuary Cities, Focusing Events, and the Solidarity Shift: A Standard Measurement of the Prevalence of Victims in the Narrative Policy Framework”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 166-196. doi.org/10.15788/npf7

Stephan, Hanes R. 2020. Shaping the Scope of Conflict in Scotland’s Fracking Debate: Conflict Management and the Narrative Policy Framework. Review of Policy Research 37(1), 64- 9: DOI:10.1111/ ropr.12365

Wolters, Erika Allen, Michael D. Jones, and Kathryn Duvall. 2022. “A Narrative Policy Framework Solution to Understanding Climate Change Framing Research”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 222-242. doi.org/10.15788/npf9

Wolton, Laura P., Deserai A. Crow, and Tanya Heikkila. 2022. “Stepping Forward: Toward a More Systematic NPF with Automation”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 40-90. doi.org/10.15788/npf3