Kuhika Gupta; Joseph Ripberger; Andrew Fox; Hank Jenkins-Smith; and Carol Silva

Kuhika Gupta*, University of Oklahoma

Joseph Ripberger, University of Oklahoma

Andrew Fox, University of Oklahoma

Hank Jenkins-Smith, University of Oklahoma

Carol Silva, University of Oklahoma

Abstract

This study combines insight from discourse network analysis (DNA) and the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) to develop a new approach to studying narrative discourse within and across policy coalitions. The approach facilitates examination of narrative cohesion, which may impact the stability of coalitions as well as narrative discourse on policy change. We demonstrate the value of the approach by using it to study meta narratives on Twitter within and across groups of policy actors who support and oppose the expansion of nuclear energy in the United States. The approach reveals a variety of patterns that are unlikely to be seen using more common approaches to narrative policy analysis. Most notably, there were signs of narrative cohesion within both groups, but there were also slight fissures that may indicate strategic efforts to communicate with different constituents or fault lines that threaten group stability. These findings set the stage for future work on the relationship between narrative cohesion and policy outcomes.

*Corresponding author: kuhikagupta@ou.edu

To cite the chapter: Gupta, Kuhika, Joseph Ripberger, Andrew Fox, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Carol Silva. 2022. “Discourse Network Analysis of Nuclear Narratives”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 13-39. DOI: doi.org/10.15788/npf2

Introduction

Stories help people make sense of the world. Policy narratives are stories that advocacy groups tell to influence policy outcomes. The Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) has created a systematic way to analyze the structure of policy narratives and how they inform the policy process (Shanahan et al., 2011). According to the NPF, policy narratives have core elements such as a plot, setting, moral, and characters. Policy actors adopt strategies to strengthen/weaken narrative dissemination and influence public support. A core strength of the NPF is its versatility and productivity across policy settings, levels of analysis, methodologies, and types of data.

Researchers have shown that the NPF “works” and provides significant insight into policy dynamics in many different policy areas and policymaking settings (McBeth et al., 2005; Jones & McBeth, 2010; Jones et al., 2014). Likewise, research shows that the NPF explains policy-relevant actions and relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions by spawning variants of the framework that focus on micro, meso, and macro levels of analysis (Shanahan et al., 2018). This variety in where and how researchers are using the NPF generates significant diversity in the methodologies and types of data that researchers are using to test and refine the framework. NPF studies use everything from qualitative interviews and content analysis to descriptive statistics and multiple regression to explore the stories that advocacy groups use to influence policy outcomes (McBeth et al., 2010; Gottlieb et al., 2018; McBeth & Lybecker, 2018; Merry, 2018; Shanahan et al., 2018). In some studies, these stories come from lengthy policy documents like speeches, platforms, and statements at public meetings; in others, the stories come from bits and pieces of information that advocacy groups release in media interviews (Lawlor & Crow, 2018; Merry, 2018; Shanahan et al., 2013; Weible et al., 2016) and on new media platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter (Shanahan et al., 2013; Merry, 2016; Gupta et al., 2018; Merry, 2020).

This study continues in this tradition of diversity by assessing the utility of discourse network analysis (DNA) for studying intersecting policy narratives among groups of policy actors who share core policy beliefs and goals. DNA is new to the NPF, but network analysis is not. Past research has shown that network maps can assist in illustrating polarization in policy narratives; groups who support and oppose hydraulic fracturing utilize virtually opposite frames and characters in the narratives they use to discuss the issue (Heikkila et al., 2014). Likewise, past work indicates that network analysis can assist in exploring relationships among narrative characters. Weible et al., (2016), for example, use network analysis to show that competing groups often use the same characters, but cast them in completely different roles; one group’s hero is often the opposing group’s villain. Finally, previous research highlights the utility of network analysis for analyzing the micro narratives that structure group discussion about complex policy issues (Smith-Walter et al., 2020).

Although past research provides insight about relationships among narrative actors and elements, it uses relatively simple network visualizations and concentrates on actors rather than the stories that bind them together. The DNA approach we use is motivated by the need to provide a more complex view of the network interdependencies among not only actors but also narrative elements. Adopting DNA as a methodology, we are able to systematically characterize and compare narrative structures within policy groups. Specifically, we use DNA to explore narrative discourse structures in two different ways. First, we construct and analyze networks of policy actors who share common beliefs. This analysis allows us to study the cohesiveness of narrative discourse within policy groups. Are actors contributing to a single overarching narrative that seems to unite the group? Or are actors using multiple, competing narratives that may undermine group unity or speak to different constituencies? Next, we construct and analyze networks of narrative elements that allow us to investigate the structure of narrative discourse. In so doing, we identify clusters or sets of narrative elements that point to underlying themes and possible cleavages in narrative discourse among actors who share core policy beliefs.

In addressing these questions, we contribute to nascent literature on the role of narrative cohesion in the policymaking process. Broadly, narrative cohesion measures the extent to which policy actors who share core beliefs use the same narrative elements and strategies when attempting to influence policy outcomes. In cohesive groups, policy actors are on the same page; they use the same plot lines, settings, and characters when publicly discussing policy problems and solutions. In less cohesive groups, policy actors share core beliefs, but use different storylines and feature different characters in those storylines in public dialogue. Past work on the NPF posits that narrative cohesion plays an important role in the policy process. Shanahan et al. (2011), for example, hypothesize that cohesive groups have more influence on policy outcomes than less cohesive groups. Subsequent work, such as Shanahan et al. (2013), reinforces the importance of narrative cohesion but suggests that incohesive groups who amalgamate a variety of storylines and elements might be more effective than cohesive groups because the narratives they use resonate with different constituencies. Which proposition is correct? Researchers have yet to settle this question because it can be difficult to define and operationalize narrative cohesion. DNA helps to solve this problem by allowing us to systematically analyze relationships among narrative actors and elements within policy groups.

Finally, this study also contributes to diversity within the NPF by expanding the use of social media data in narrative analysis. As with network analysis, social media analysis is increasingly common in NPF research, but its use is inconsistent from study to study and there is relatively little theory to guide the data collection process. We address these issues by providing a transparent and replicable data collection methodology that begins with the identification of policy actors and policy beliefs. From there, we explain how to collect and code data using an NPF codebook that we adapt for DNA.

Past Research and Current Synergies

Theories of policy processes often focus on how groups of actors with like beliefs interact to influence policy outcomes; groups who agree with current policy coordinate to collectively maintain the status quo while groups who disagree conspire to bring about policy change. Given the importance of group interaction, many theories of the policy process argue that relationships, group coordination, and collective information processing are key features of the policy process (Sabatier, 1988; Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Baumgartner & Jones, 1991; Roth & Bourgine, 2005). Policy actors coordinate with like-minded groups in multiple ways. In some cases, they directly coordinate on tangible actions; for example, they might jointly file a lawsuit or cohost a rally. More frequently, they indirectly coordinate by co-contributing to public debate about a policy; for example, actors who share beliefs often comment on proposed rules and regulations and provide testimony at congressional hearings (Weible et al., 2019). In some cases, indirect coordination inspires direct coordination. The public statements that policy actors make can serve as signaling mechanisms to actors who share beliefs and preferences, prompting them to seek one another out and form a coalition to collectively fight for policy outcomes (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith 1993; Weible & Sabatier, 2017; Jenkins-Smith et al., 2017; Weible & Ingold, 2018; Weible et al., 2019). The NPF provides structure and meaning to these statements, arguing that narratives are the primary means through which policy actors organize, process, and communicate information (Berinsky & Kinder, 2006; Gerrig & Egidi, 2003; Klein, 2003; Jones & McBeth, 2010).

Narrative Policy Framework

The NPF theorizes that policy actors use narratives to shape the policymaking process. Narratives provide policy actors with stories that contain plots, characters, settings, and morals that help communicate policy positions (Jones et al., 2014; Shanahan et al., 2011). Among its core assumptions is the assertion that policy narratives are socially constructed and have specific and identifiable structures in the form they take and the content they share. Narrative form and narrative content make up the core components of a policy narrative. Form is illustrated in the policy setting (space and time), characters (heroes, villains, and victims), plot (organizes action), and moral of a story (policy solution). Narrative content is made up of the set of values or beliefs encompassed within the narrative as well as narrative strategies geared towards manipulating or controlling the policy processes (Shanahan et al., 2018). This study focuses on one aspect of narrative form: the characters that policy actors use.

Narrative research can be conducted on three levels of analysis: micro, meso, and macro. At the micro level, the focus is on how individuals form narratives and are in turn influenced by narratives they encounter. The meso scale moves the analysis to how groups, coalitions, and organizations construct and share policy narratives to affect outcomes. Macro-scale analysis is characterized by a focus on narratives that are pervasive throughout society, cultures, and institutions and how these macro narratives influence the policy process (Shanahan et al., 2018). Over the years, NPF researchers have studied narratives and their role in the policy process on all three levels of analysis. In this study, we focus on the meso scale by looking at how policy actors interact in groups to collectively shape narrative discourse.

Discourse Network Analysis (DNA)

DNA is an emerging approach to the study of public policy (Ingold, 2011; Leifeld & Haunss, 2012; Leifeld, 2013; Fisher et al., 2013; Rinscheid, 2015; Leifeld, 2016; Wagner & Payne, 2017; Buckton et al., 2019; Fergie et al., 2019; Nagel & Satoh, 2019; Abzianidze, 2020; Bhattacharya, 2020; Bossner & Nagel, 2020; Leifeld, 2020). The theory underlying DNA is that policy discourse is inherently a group activity, wherein individuals and organizations learn and interact with one another to shape the public policy debate. Competing groups of policy actors engage in an interactive exchange of ideas through public statements in an effort to make their positions known, thereby reducing uncertainty and enabling coordination (Hajer, 1993, 1995, 2002; Leifeld & Haunss, 2012; Leifeld, 2013). Much like the NPF, a core assumption underlying DNA is that policy discourse helps individuals and society make sense of the world around them by providing a lens through which to interpret events, ideas, and risks (Goffman, 1974; Kühberger, 1998; Miller, 2000).

To understand and analyze the structure of policy discourse, DNA makes use of networks. Networks represent collections of relationships, identified using graph theory and data visualization to visualize the nodes and edges that connect policy actors (Borgatti et al., 2013; Kadushin, 2012). Actors are typically the nodes in DNA networks and beliefs, perceptions, and preferences are generally the edges that connect the actors (Leifeld, 2017). DNA provides insight into the policy process by systematically analyzing the patterns of nodes and edges—the relationships—that define policy coalitions. Through these efforts, researchers have been able to track the evolution of policy coalitions over time to explain why policy shifts happen as well as the timing of changes in government pensions (Leifeld, 2013; 2016), software patents (Leifeld & Haunss, 2012), higher education (Naegler, 2015), and consumption taxes (Buckton et al., 2019; Fergie et al., 2019). Researchers have also used DNA to investigate the dynamics of polarization as well as probe the nature of support and opposition to policy change in the context of highly contentious issues, such as climate change (Fisher et al., 2013; Ingold, 2011; Wagner & Payne, 2017), urban development (Nagel & Satoh, 2019), and nuclear energy (Rinscheid, 2015).

In addition to providing insight into the relationship between policy actors within coalitions, DNA integrates network analysis and qualitative content analysis in ways that can help researchers compile and make sense of the information fragments that policy actors share in short public interviews and social media statements (Leifeld, 2017). In isolation, it can be difficult to make sense of each bit of information; when looking at the beliefs, perceptions, and preferences that actors disclose on a tweet-by-tweet basis, it can be difficult to see the forest through the trees.

Though DNA researchers typically focus on the relationship between actors within a network, DNA can also assist in exploring the connection between beliefs, perceptions, and policy preferences in a network (Leifeld, 2013; Rinscheid, 2015; Leifeld, 2016; Buckton, Fergie et al., 2019). In these networks, beliefs, perceptions, and preferences are the nodes and policy actors are the edges that connect them. These networks show us how beliefs, perceptions, and preferences coalesce to form patterns in policy discourse. They show us the beliefs that generate perceptions and the perceptions that stimulate preferences. In other words, they help clarify the system of beliefs that binds policy actors in a network.

In principle, DNA is highly compatible with the NPF. Both approaches embrace the core assumptions of the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). They theorize that policy actors interact in groups to collectively shape policy discourse. Likewise, both approaches suggest that policy discourse can profoundly impact policy outcomes. Finally, both approaches embrace the importance of beliefs, perceptions, and preferences in the policymaking process. The primary distinction between the two approaches is one of focus, not theory. DNA generally focuses on the belief systems that tie policy actors, whereas the NPF focuses on the narratives that unite them. This difference is relatively easy to overcome. With simple modification, DNA can illuminate the study of narratives in the policy process. If we replace beliefs, perceptions, and preferences with narrative elements, we can use DNA to characterize and explore narrative discourse using the two network approaches we describe above.

First, we can construct and analyze narrative networks of policy actors who share narrative content. In these networks, policy actors are the nodes and narrative elements (e.g., characters) define the edges that connect the actors who share commonalities and separate actors who do not. This type of analysis allows us to address core questions about narrative cohesion in policy groups. Are actors with like beliefs contributing to a single overarching narrative that seems to unite the group? Or are they using multiple, competing narratives that may undermine group unity and/or speak to different constituencies in the policy process? Existing hypotheses about narrative cohesion within NPF remain largely untested (Shanahan et al., 2011; Shanahan et al., 2013), and this study could provide a way to measure character prioritization and congruence among a set of policy actors with shared policy beliefs.

Second, we can invert the analysis by constructing and analyzing networks of narrative elements that relate through common actors. In these networks, narrative elements, such as the characters in a story, are the nodes and policy actors are the edges that delineate the relationship between narrative elements. Using this type of network, we can identify clusters or sets of narrative elements that point to underlying themes in narrative discourse. In this chapter, we demonstrate the utility of both approaches, and DNA more generally, by using them to characterize and explore narrative discourse in opposing coalitions that have long been fighting in support and opposition to nuclear energy in the United States. We use nuclear energy policy in the United States to explore the synergies between DNA and the NPF because nuclear energy policymaking offers a clear set of competing groups who have been telling relatively consistent stories about the technology for many years.

Nuclear Energy in the United States

The nuclear energy policy subsystem in the United States currently consists of two competing coalitions: a pro-nuclear coalition and an anti-nuclear coalition. Supporters of nuclear energy generally emphasize the benefits of low-cost electricity from a reliable, secure, and carbon-free source (de Groot & Steg, 2010). Research suggests that public willingness to accept nuclear energy often depends on the perception that the economic benefits outweigh the cost (Kim et al., 2014). Additionally, public support has been found to be closely tied to trust in government officials, agencies, industry representatives, and plant employees, which tend to lower the perceived risks of nuclear energy and expand public support (Poortinga & Pidgeon, 2003; Whitfield et al., 2009; Besley, 2012). As such, the pro-nuclear coalition has frequently argued that nuclear energy presents concentrated costs and diffused benefits in an effort to continue investment in the development of new technology, licensing, and siting nuclear power plants (Gupta et al., 2018).

Opponents of nuclear energy generally focus on the risks associated with accidents, radiation exposure, and hazardous nuclear waste (Keller et al., 2012; Parkhill et al., 2010). The historical legacy of high-profile accidents at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima has helped sustain persistent public opposition and widespread attitudes that reflect a not in my backyard (NIMBY) mindset, bringing the nuclear industry to a standstill (Abdulla et al., 2019; Mazmanian & Morrell, 1994). Informed by this mindset, members of the anti-nuclear coalition frequently argue for the elimination of nuclear energy by phasing out existing nuclear power plants and not constructing new facilities in favor of alternative sources of electricity, such as renewables (Gupta et al., 2018). As a result, the anti-nuclear coalition has often pursued a strategy that seeks to expand the number of people involved in the debate over nuclear energy by focusing on the concentrated benefits and diffused costs posed by the risks associated with nuclear power (Gupta et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2018).

Thus far, work on narratives about nuclear energy, both in the United States and internationally, has focused on how a single group from the pro or anti-nuclear coalition uses narratives to pursue policy goals. This study builds on existing NPF studies on nuclear energy by exploring how multiple policy actors are producing narrative elements in groups and whether groups are using the same elements to engender narrative cohesion.

Data and Methods

Data Collection

Nuclear energy policy is a complex issue that involves many types of policy actors, such as government officials, agencies, non-profit organizations, and issue experts. While this multitude of actors provides a great opportunity to collect a diverse array of data, it also poses challenges. At times, it seems like almost everyone in the policy-making process has something to say about nuclear energy. This can make it difficult to identify relevant policy actors who consistently participate in the policy process and contribute to the policy discourse. Additionally, it can be difficult to identify actors who are members of the pro/anti group among the many isolates who espouse opinions but do not interact with anyone in the group. Finally, it can be difficult to locate a consistent stream of narrative content (data) where actors in groups collectively contribute to narrative discourse.

We attempt to address these challenges by studying narrative discourse on Twitter, a social media platform that policy actors routinely use to shape policy discourse by interacting with fellow policy actors and members of the public. The use of Twitter data to analyze narrative construction and dissemination is not new within the NPF. For example, Merry (2016) examines the debate over gun policy, finding that advocacy groups are able to effectively frame policy issues on Twitter. Taking this line of reasoning even further, Gupta et al. (2018) not only find that policy actors use narratives on Twitter, but they also employ specific strategies on social media that seek to expand or contain the scope of the conflict over nuclear energy policy in the United States. While the use of Twitter data has been increasingly popular among NPF scholars (Gupta et al., 2018; Merry, 2016; Shanahan et al., 2018), its use has been inconsistent from study to study, and there are no systematic guidelines to guide the data collection process. Given the wide array of individuals and organizations that are active on Twitter, as well as the massive amounts of data (tweets) about topics like nuclear energy, a transparent and replicable process for identifying relevant actors and the narrative discourse is imperative.

The process we used involves three steps:

(1) identify relevant policy actors through modes of participation in the policy process;

(2) search Twitter to identify which actors have active accounts and interact with others in the group; and

(3) collect messages and classify narrative discourse.

Beginning with step one, we define policy actors as individuals or organizations that formally and routinely participate in the policy process. While there are many ways to formally participate in the policy process, we followed past research in using two forms of participation to identify policy actors in this study: testimony at congressional hearings and comments on regulatory actions (Weible et al., 2019). From 2014 to 2019, there were 46 hearings about nuclear energy in Congress and 101 regulatory actions by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC); 663 unique individuals or organizations (policy actors) participated in these processes by providing witness testimony or submitting a comment. We reviewed every statement/comment to identify the policy actors that were supportive of nuclear energy and those who were opposed. According to our analysis, 377 were supportive, 238 were opposed, and 48 did not indicate a policy position. Because we are interested in policy narratives (which require a policy stance), we focused on the actors who indicated a clear position.

In step two, we searched for the 615 actors who indicated a clear policy position on Twitter. We found active accounts for 211 (34.31%) of the actors; 120 of the pro-nuclear actors and 91 of the anti-nuclear actors had active Twitter accounts when this analysis began. After identifying these accounts, we analyzed messages from each actor’s account to identify signs of group interaction, which we operationalized as re-tweeting or mentioning a policy actor with a like-policy position. Of the 120 pro-nuclear actors we were able to identify on Twitter, 33 (27.5%) had engaged in some form of interaction with another actor in the pro-nuclear group. Of the 91 anti-nuclear actors, only 15 (16.5%) had engaged in some form of interaction with another actor in the group. Using this list of 48 policy actors with active Twitter accounts, we connected to Twitter’s streaming API to capture messages about nuclear energy from January 2019 to June 2019. Together, the 48 actors we identified published 1,026 tweets during this timeframe; 735 of the messages were from pro-nuclear actors, and 291 were from anti-nuclear actors.

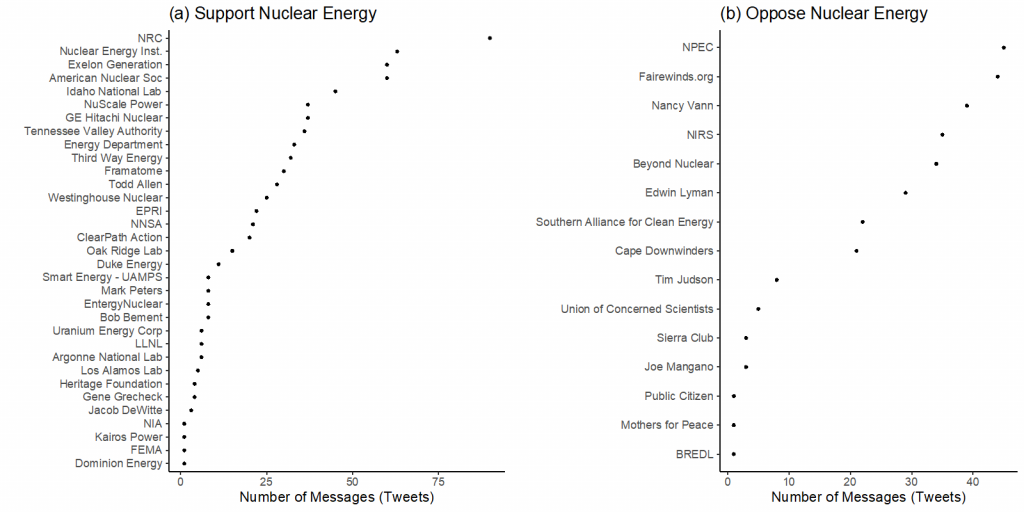

Figure 1 lists the policy actors in each of the groups. Though we believe that the methodology we used to identify these actors and collect their messages is transparent and replicable, it is important to note that the Twitter domain is not necessarily representative of the nuclear energy policy domain as a whole. We know that some actors participate in the policy process but do not have or routinely use Twitter accounts. Likewise, the narratives that policy actors espouse on Twitter are not necessarily the same as the narratives they advocate in other public consumption documents. Finally, the timeframe we chose for this analysis necessarily omits the variety of actors and narratives that were not on Twitter from January 2019 to June 2019. We chose to focus on this timeframe because it captures conversation about nuclear energy in relation to the Green New Deal (GND), a resolution in Congress that was put forth by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Edward Markey on February 7, 2019. Among other things, the GND called for the United States “to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions through a fair and just transition for all communities and workers.” Nuclear energy became a flashpoint in this conversation because proponents of the GND were torn in their views about the role of nuclear energy in transitioning to net-zero emissions; some believed in President Obama’s “all-of-the-above” approach that included nuclear energy; others were explicitly opposed to it.

Figure 1. Policy Actors by Group and Number of Messages

Content Analysis

Given the exploratory nature of this study, we chose to focus on the use of characters (heroes, villains, and victims) as core narrative elements to identify shared narrative discourse. In future research, we intend to expand the analysis to include other narrative elements as well as narrative strategies. Two independent coders manually analyzed each tweet for the presence of characters. Character types were coded according to the NPF codebook, which defines heroes as those who take action to fix a problem, villains as those whose actions harm others, and victims as those being harmed (Jones & McBeth, 2010; Shanahan et al., 2018). Both animate and inanimate objects were considered characters. Moreover, characters were identified if they appeared anywhere in a tweet rather than in conjunction with other elements. In other words, heroes did not have to appear in relation to villains or victims and vice versa.

Coders identified the type of character present (hero, villain, victim), if any, followed by a subtype that fell into one of 35 predefined categories (see Appendix for the codebook). Character subtypes were designed to provide specificity to each character type as it relates to the topic of nuclear energy. Heroes and villains were divided into five subtypes, which were further disaggregated into specific types of characters: business and industry (nuclear energy, nuclear industry representatives, fossil fuels, renewables, technology, advanced nuclear technology, nuclear waste, and business entrepreneurs), environment (carbon emissions, climate change, and physical environmental phenomena), government and public sector (policy and legislation, government officials, and government agencies), cultural and historical (language, events, and historical memories), and other (advocacy organizations, academics, media, general people, and health). Victims were similarly divided into human (humans, children, and communities), wildlife and natural environment (physical environment, animals), economic (jobs, taxpayers, and budgets), cultural and historical (language, events, and historical memories), and other (the state and nuclear energy). While this coding strategy attempts to preserve as much nuance as possible across the characters that actors use, it is important to note that it generates some abstraction for the sake of comparison. This abstraction may cause fuzziness in the analysis of narrative networks. For example, if different actors use “industry representatives” as villains in their narratives, they will be given the same code, even if they are talking about different individuals or organizations. This will make it look like the actors are telling the same story, even if the story features different people and organizations.

As with all NPF coding projects, there was some subjectivity in the decisions that coders made. However, the kappa coefficients shown in Table 1 suggest that the data are fairly reliable. Using Landis and Koch (1977) as a yardstick, all of the coefficients demonstrate “substantial” inter-rater reliability.

Table 1. Cohen’s kappa coefficients (κ)

| Present | Character Subtype | |

|---|---|---|

| Hero | 0.767 | 0.721 |

| Victim | 0.717 | 0.687 |

| Villain | 0.796 | 0.741 |

Discourse Network Analysis

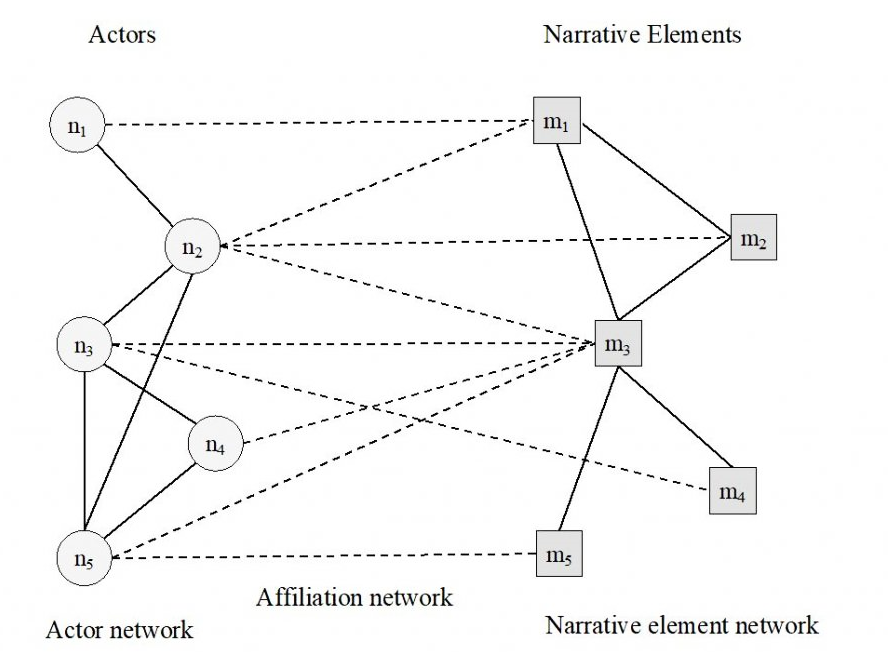

Akin to actor-to-actor and concept-to-concept networks in DNA, we constructed two types of networks to depict and statistically analyze narrative discourse from the pro- and anti-nuclear energy groups: (1) networks of policy actors who share narrative elements and (2) networks of narrative elements that relate through common actors. As shown in Figure 2, the networks use cross-network ties (affiliation) to identify ties between the nodes in each of the networks. To construct the network of policy actors, we defined the relationship (adjacency) between actors (n) by detecting instances in which the actors used the same narrative elements (m). For example, actor n1 (in Figure 2) shares a tie with actor n2 because they use a common narrative element m1. We did the opposite to construct the network of narrative elements. We defined the relationship between narrative elements (m) by detecting instances in which the elements were used by the same policy actors (n). For example, narrative element m1 shares a link with element m2 because they were used by the same policy actor n2.

Figure 2. Discourse Network Analysis of Policy Actors and Narrative Elements

In addition to graphically representing and visually analyzing the topology of these networks, we used two network statistics/methods to analyze narrative discourse from the pro- and anti-nuclear energy groups. First, we calculated degree centrality scores to measure the number of connections that each node (actor/narrative element) in the network had with other nodes (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). We used these scores to identify the actors and narrative elements that played an important role in shaping narrative discourse; they pointed us towards the actors that were most likely to shape a group’s narrative and the characters that were most likely to intersect multiple narratives. Note that by definition, there is a positive correlation (r = 0.75) between message frequency and degree centrality. Actors who contribute many messages to the dataset generally have more connections than actors who contribute few messages. While strong, this relationship is not absolute because some of the actors who contribute many messages utilize multiple narrative elements that connect them with multiple actors, whereas others repeatedly utilize the same elements, limiting their narrative connections with others.

Next, we used the Louvain community detection algorithm to identify subcommunities of actors and narrative elements within the pro-nuclear and anti-nuclear discourse coalitions (Blondel et al., 2008). This allowed us to explore cohesion in the networks of actors and the dominant patterns of narrative discourse in each of the groups. In short, Louvain community detection uses an optimization algorithm to assess modularity (dense connections) in different portions of a network. When the algorithm identifies an especially dense part of the network, it labels the nodes/edges in that part of the network a community. In this study, communities are important because they indicate the underlying structure and cohesion of a network. Networks with many separate communities are less cohesive than networks with relatively few, overlapping communities.

To date, most DNA studies rely on the Discourse Network Analyzer software created by Leifeld (2017; available here: https://www.philipleifeld.com/software/software.html) to qualitatively code statements from actors and extract network data for analysis. In this study, we chose not to use the DNA software because the file structure of Twitter data currently prevents importing the data in an easily useable fashion and our use of the NPF codebook for characters differs from DNA’s focus on beliefs, perceptions, and preferences. To join DNA with the NPF, we manually coded each statement in a spreadsheet, which was then uploaded into R, where we used the igraph package to create the DNA matrices and calculate network statistics. We used Gephi to visualize the networks.

Results

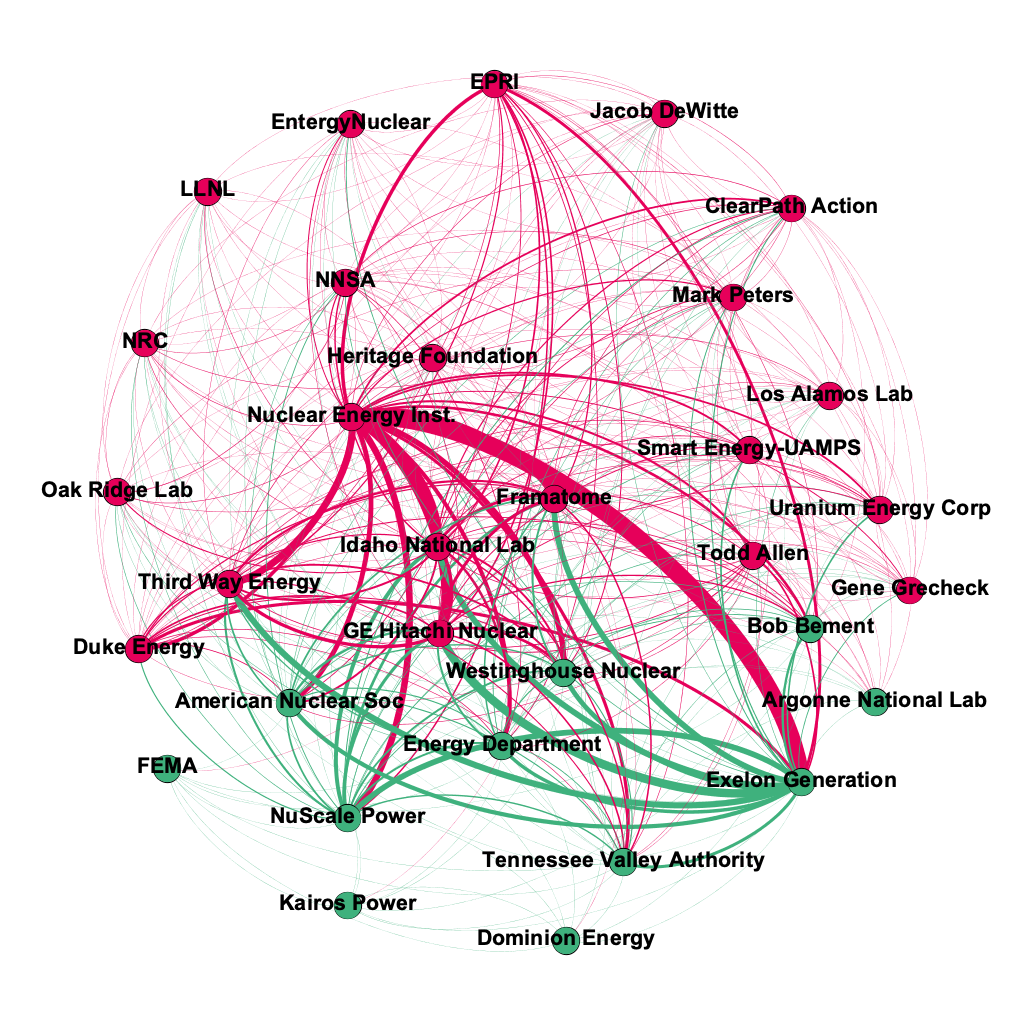

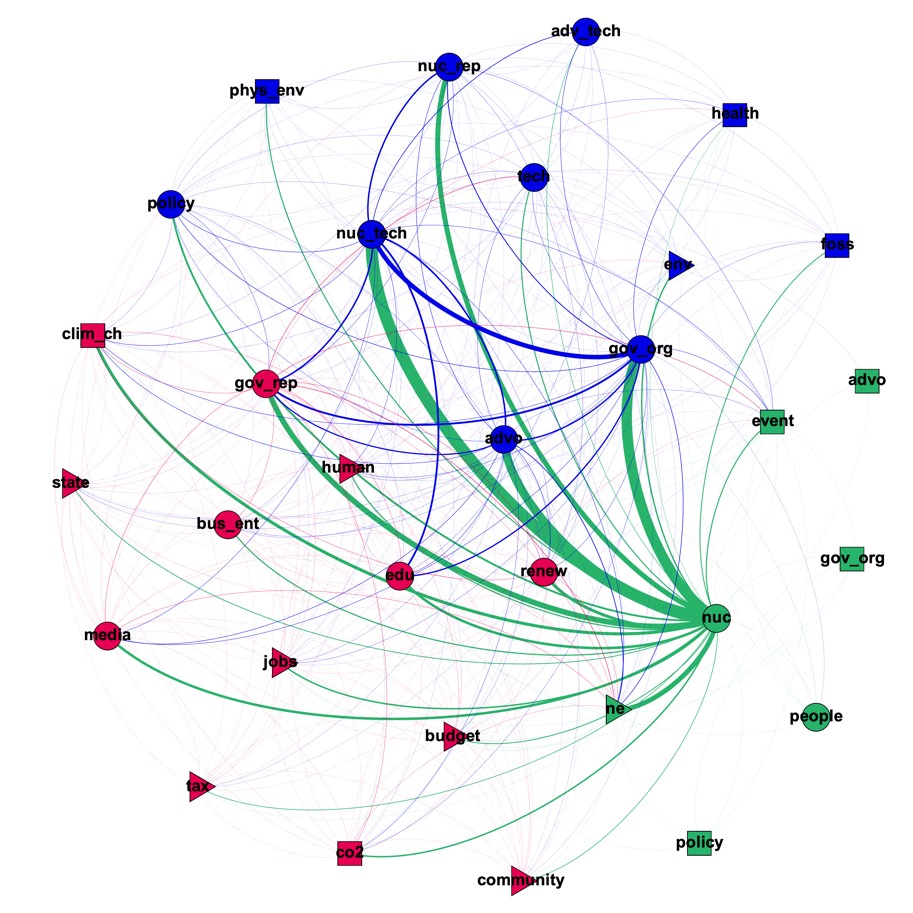

Discourse Networks of Policy Actors

Figure 3 graphically depicts the network of policy actors (nodes) who support nuclear energy. The ties (edges) between actors represent common narrative elements (heroes, villains, and victims). Edge thickness in the networks indicates commonality—actors who frequently use the same narrative elements in public discourse have thick ties; actors who infrequently use the same elements have thin edges. The green and red edge colors represent two distinct subcommunities that emerged from the Louvain community detection algorithm.

Figure 3. Network of Policy Actors who Support Nuclear Energy

Using the network visualization alone, we can begin to identify patterns in the shared narrative discourse. Most notably, for example, we see that the Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) appears to share, if not structure, much of the narrative discourse that comes from actors who support nuclear energy. Likewise, we see a strong tie between NEI and Exelon Generation, emblematic of the strong relationship between trade associations (NEI) and private energy companies (like Exelon). These policy actors frequently contribute to narrative discourse, often using the same heroes, villains, and victims to propagate support for nuclear energy. Despite frequent contributions, NEI and Exelon have relatively low centrality scores in comparison to the American Nuclear Society (ANS) and the Department of Energy (DOE), who have more connections to a wide variety of actors in the group. These connections may reflect a slight distinction between scientific agencies/societies (DOE/ANS) and industry groups/companies (NEI/Exelon). Scientific actors seem to use diffuse narratives with many different elements in place of tight narratives that focus on the same cast of characters; by doing this, they establish narrative connections with more actors in the group, but the ties are relatively weak.

Network statistics allowed us to more fully examine this distinction by identifying clusters in the network—communities that overlap in the narrative they formulate. In highly cohesive discourse networks, where everyone shares an underlying narrative, there might be a single community or a dominant community and a fringe community or two that are relatively distant from the core group. As shown in Figure 3 the bottom (green) community is largely made of actors who produce or advocate for traditional nuclear energy, whereas the top (red) community seems to include actors who focus on the advancement of new nuclear technology. The NEI predominately fits in the new technology community but shares strong ties with the traditional nuclear energy group as well. As noted above, this suggests that the NEI shares (and possibly drives) much of the narrative discourse that comes from both groups in the network.

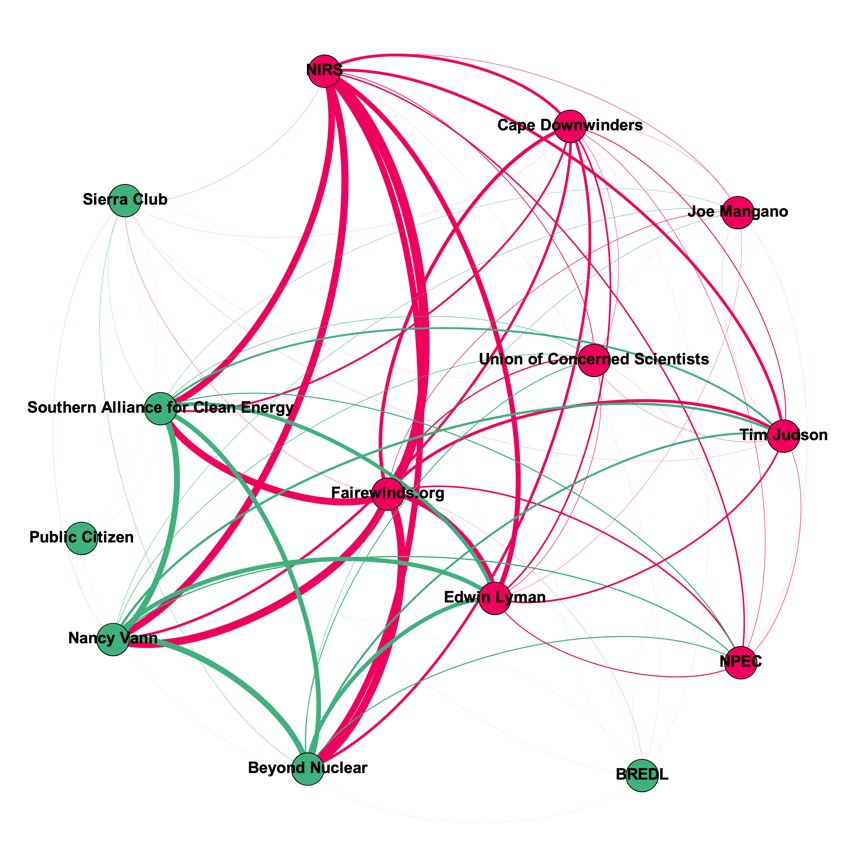

Figure 4. Network of Policy Actors who Oppose Nuclear Energy

The opposition network (Figure 4) is visually sparse in comparison to the support network because there were fewer actors in the group at the time of this analysis. Nevertheless, there are quite a few narrative commonalities that connect the actors in the network. The thickest ties are between the Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS), the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, Nancy Vann, Fairwinds.org, and Beyond Nuclear, though there are many ties in the network that are almost as strong. Like many in the network, most of these actors are non-profit organizations (or individuals who represent non-profit organizations) that stress the risks of nuclear energy and promote renewable alternatives. Fairwinds.org was an important hub in the narrative network, connecting narrative elements from many different organizations. This finding may suggest one of two alternatives: (1) that Fairwinds.org is shaping the narratives that disparate groups subsequently adopt; or (2) that Fairwinds.org is a narrative clearing house, borrowing and sharing elements of stories from many different actors at once.

As in the support network, there are two communities in the opposition network that are roughly even in size. Unlike the support network, where there are relatively obvious differences in the types of actors in each community, there are no obvious differences between the actors in the two communities. Nevertheless, the communities seem to be using slightly different narrative elements when contributing to public discourse.

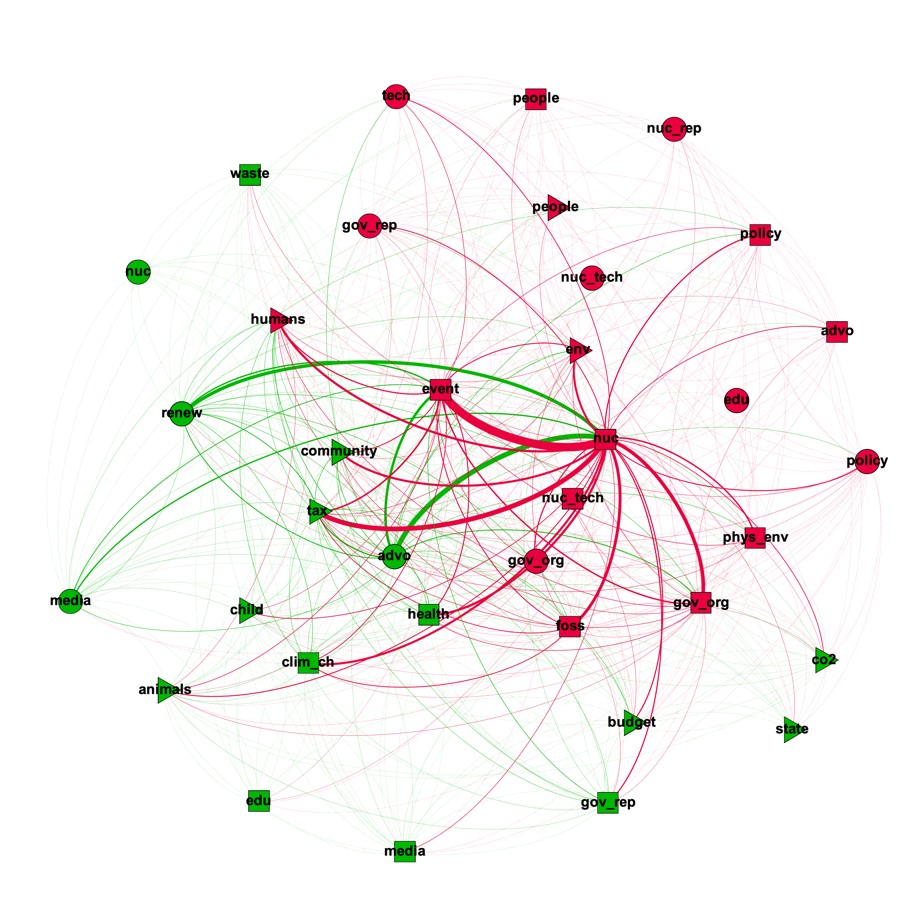

Discourse Networks of Narrative Elements

Figure 5 graphically depicts the network of narrative elements (nodes) that relate through actors who support nuclear energy (edges). The edges between the narrative elements indicate common actors. For example, the edge between climate change (the villain) and nuclear energy (the hero) shows that these elements were brought up by one or more of the group members in the network. Thick edges indicate a strong affinity between the narrative elements that arose because they were jointly brought up by multiple actors. Through a combination of node centrality and edge thickness, we can begin to identify the most important meta or overarching narratives that seem to underlie group discourse, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Network of Narrative Elements in Support of Nuclear Energy

[Circle = Hero, Square = Villain, Triangle = Victim]

Unsurprisingly, nuclear energy (the hero) is the primary protagonist in the network. It has the highest degree of centrality and shares the thickest ties with other core elements in the network, including the heroic government organizations, advocacy groups, renewable energy sources, and new nuclear technologies that collectively fight to save humanity and the environment (the primary victims) from climate change and carbon emissions (the most prominent villains).

Consistent with the network of actors, there are three primary clusters in the network of narrative elements in support of nuclear energy, suggesting slight variation in the overarching narrative that underlies group discourse. The top (blue) narrative highlights the importance of new technology in promoting the next generation of nuclear power in the United States. The middle (green) narrative, focusing on nuclear energy as a whole, emphasizes the general benefits of nuclear energy, including low carbon emissions and economic growth. The bottom (red) narrative is the least pronounced but seems to focus on economic issues such as the loss of jobs, the threat of increased utility costs to household budgets, or taxpayer burdens as a result of prematurely closing nuclear power plants. The fissure between the two dominant clusters (blue and green) is representative of an ongoing debate among pro-nuclear advocates about the future of nuclear energy in the United States. Some groups highlight the emergence and importance of new nuclear technologies like small modular reactors (SMRs) and molten salt reactors (MSRs) that will revolutionize and reinvigorate the nuclear industry, making it a safer, more sustainable, and cost-competitive alternative to fossil fuels. Others emphasize the importance of existing technology in providing baseload electricity, asserting the need to keep existing nuclear plants running.

Figure 6. Network of Narrative Elements in Opposition to Nuclear Energy

[Circle = Hero, Square = Villain, Triangle = Victim]

As illustrated in Figure 6, Nuclear energy is also the primary protagonist in the network of elements in opposition to nuclear energy, but this time it is the villain that joins forces with catastrophic accidents (such as Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima), public health risks, climate change, and fossil fuels to harm humanity, the environment, taxpayers, and communities. Advocacy groups and renewable energy are the heroes that are working to protect the victims. In some narratives, government organizations are heroes that protect the people; in others, government organizations are villains that protect the nuclear industry.

There are two clusters in the opposition network, indicting a slight division in the meta narrative discourse that opposing groups use when fighting against nuclear energy. There is considerable overlap between the clusters, but the left (green) narrative seems to focus more heavily on climate change, renewable energy, and the unnecessary health risks of nuclear energy and nuclear waste. The right (red) narrative focuses a bit more on economic arguments against nuclear energy; it is too expensive and places too much of a burden on taxpayers and communities. This division is common in elite circles—staunch environmentalists oppose nuclear energy because it is dangerous and unnecessary whereas climate change advocates generally reject it because it is increasingly less cost competitive with alternative sources of electricity, such as wind and solar energy.

Discussion and Conclusion

Policy actors and groups tell stories to influence policy support, but their stories do not exist in isolation. The stories constructed by different actors form collective meta narratives that co-emerge and co-exist across groups of actors who share policy beliefs and goals. The primary objective of this study was to assess the utility of DNA for examining the collective nature of these meta narratives and the groups of actors who co-construct them. We used Twitter messages from groups of policy actors who support and oppose nuclear energy to accomplish this objective. On the whole, we believe that the study provides evidence that DNA can reveal things about meta narratives that are unlikely to be seen using more common approaches to narrative policy analysis.

DNA of policy actors reveals information about the cohesion of narrative discourse within the two policy groups. On the whole, the groups were relatively cohesive, but there were slight fractures that may reflect growing discordance in narrative discourse and group unity or efforts to speak to different constituents. Most notably, there were two relatively distinct communities in the network of policy actors who support nuclear energy; one was largely made of actors who produce or advocate for traditional nuclear energy, and the other included scientists and others who advocate for new nuclear technologies. There were also two distinct communities in the network of policy actors who oppose nuclear energy, but—absent information about the narrative structure underlying the cleavage—it was difficult to identify the difference between the two sets of actors.

DNA of narrative elements allowed us to more thoroughly investigate the differences between clusters of actors by detailing the underlying structure and content of narrative discourse that connected actors in the sub-group communities. Consistent with our analysis of the differences between actors, our analysis of communal narrative elements showed that there were two competing meta narratives in the pro-nuclear group. The first narrative community focused on the general benefits of nuclear energy in the fight against fossil fuels and climate change. The second focused on the role of new technologies in modernizing nuclear energy. This fault line reflects an ongoing debate among advocates about the future of nuclear energy in the United States. One side of the debate argues that new technologies are necessary to make nuclear power safer, more sustainable, and cost-competitive. The other side emphasizes the importance of existing technology in providing affordable, baseload electricity, asserting the need to keep existing plants running; in their view, new technologies are an unnecessary or unproven distraction.

Our analysis of the narrative elements used by anti-nuclear groups also indicated two primary meta narratives, though the contrast between the two was a bit less stark than in the pro-nuclear group. The first narrative generally focused on climate change, renewable energy, and the unnecessary health risks of nuclear energy and nuclear waste. The second focused a bit more on the economics of nuclear energy, arguing that nuclear power plants are too expensive and place too much of a burden on taxpayers and communities. This split seems to reflect an ongoing debate between historic “environmentalists” who (above all) worry about the health risks of radiation and relatively recent “climate change realists” who focus on the relative cost of nuclear energy vs. renewable alternatives.

We conjecture that fissures in narrative discourse (as witnessed in these two groups but likely indicative of other policy groups) are important to the NPF because they are likely to indicate one of three things: (1) dissonance in policy groups that may undermine the group’s ability to affect policy outcomes, (2) early signs of change in the meta narratives that policy groups are constructing. or (3) a pluralist narrative strategy whereby policy actors who share core beliefs intentionally or unintentionally construct different narratives that may resonate with different segments of the population. While this study does not provide evidence on which of these explanations is correct, it sets the stage by showing that DNA is compatible with the NPF. It also provides a transparent and replicable template for applying DNA to the NPF using social media or other forms of narrative data. These steps are important because future efforts to assess the relative merit of each explanation will require large volumes of consistent data that allow for the examination of narrative discourse, and the network structures that underlie this discourse, over time. This, we believe, is the next great frontier in DNA and NPF research—investigation of how discourse changes from month-to-month and year-to-year as long-time and new policy actors interact to jointly construct policy narratives and affect policy outcomes.

References

Abdulla, A., Vaishnav, P., Sergi, B., & Victor, D. G. (2019). Limits to deployment of nuclear power for decarbonization: Insights from public opinion. Energy Policy, 129, 1339–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.03.039

Abzianidze, N. (2020). Us vs. Them as Structural Equivalence: Analysing Nationalist Discourse Networks in the Georgian Print Media. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2605

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1991). Agenda Dynamics and Policy Subsystems. The Journal of Politics, 53(4), 1044–1074. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131866

Berinsky, A. J., & Kinder, D. R. (2006). Making Sense of Issues Through Media Frames: Understanding the Kosovo Crisis. The Journal of Politics, 68(3), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00451.x

Besley, J. C. (2012). Does Fairness Matter in the Context of Anger About Nuclear Energy Decision Making?: Anger, Fairness, and Nuclear Power. Risk Analysis, 32(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01664.x

Bhattacharya, C. (2020). Gatekeeping the Plenary Floor: Discourse Network Analysis as a Novel Approach to Party Control. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2611

Blondel, V.D., Guillaume, J., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics, P10008(10), 1-12.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing social networks. SAGE.

Bossner, F., & Nagel, M. (2020). Discourse Networks and Dual Screening: Analyzing Roles, Content and Motivations in Political Twitter Conversations. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2573

Buckton, C. H., Fergie, G., Leifeld, P., & Hilton, S. (2019). A discourse network analysis of UK newspaper coverage of the “sugar tax” debate before and after the announcement of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 490. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6799-9

De Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2010). Morality and Nuclear Energy: Perceptions of Risks and Benefits, Personal Norms, and Willingness to Take Action Related to Nuclear Energy: Morality and Nuclear Energy. Risk Analysis, 30(9), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01419.x

Fergie, G., Leifeld, P., Hawkins, B., & Hilton, S. (2019). Mapping discourse coalitions in the minimum unit pricing for alcohol debate: A discourse network analysis of UK newspaper coverage. Addiction, 114(4), 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14514

Fisher, D. R., Waggle, J., & Leifeld, P. (2013). Where Does Political Polarization Come From? Locating Polarization Within the U.S. Climate Change Debate. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 70–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463360

Gerrig, R. J., & Egidi, G. (2003). Cognitive psychological foundations of narrative experiences. In D. Herman (Ed.), CSLI lecture notes. Narrative theory and the cognitive sciences (p. 33–55). Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Gottlieb, M., Oehninger, E. B., & Arnold, G. (2018). “No Fracking Way” vs. “Drill Baby Drill”: A Restructuring of Who Is Pitted Against Whom in the Narrative Policy Framework. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 798–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12291

Gupta, K., Ripberger, J. T., & Collins, S. (2014). The Strategic Use of Policy Narratives: Jaitapur and the Politics of Siting a Nuclear Power Plant in India. In M. D. Jones, E. A. Shanahan, & M. K. McBeth (Eds.), The Science of Stories (pp. 89–106). Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137485861_5

Gupta, K., Ripberger, J., & Wehde, W. (2018). Advocacy Group Messaging on Social Media: Using the Narrative Policy Framework to Study Twitter Messages about Nuclear Energy Policy in the United States: Advocacy Group Messaging on Social Media. Policy Studies Journal, 46(1), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12176

Hajer, M.A. (1993). Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice: The case of acid rain in Britain. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, edited by F. Fischer and J. Forester, pp. 43-76. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hajer, M. A. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press.

Hajer, M. (2002). Discourse analysis and the study of policy making. European Political Science, 2(1), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2002.49

Heikkila, T., Pierce, J. J., Gallaher, S., Kagan, J., Crow, D. A., & Weible, C. M. (2014). Understanding a Period of Policy Change: The Case of Hydraulic Fracturing Disclosure Policy in Colorado: Understanding a Period of Policy Change. Review of Policy Research, 31(2), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12058

Heikkila, T., Weible, C. M., & Pierce, J. J. (2014). Exploring the policy narratives and politics of hydraulic fracturing in New York. In The science of stories (pp. 185-205). Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Ingold, K. (2011). Network Structures within Policy Processes: Coalitions, Power, and Brokerage in Swiss Climate Policy: Ingold: Network Structures within Policy Processes. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00416.x

Jenkins-Smith, H.J., Nohrstedt, D., Weible, C., & Ingold, K. (2017). The advocacy coalition framework: An overview of the research program. In C. Weible (Ed.), Theories of the Policy Process (pp. 135-171). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2010). A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to Be Wrong?: Jones/McBeth: A Narrative Policy Framework. Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x

Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E. A., & McBeth, M. K. (Eds.). (2014). The science of stories: Applications of the narrative policy framework in public policy analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kadushin, C. (2012). Understanding social networks: Theories, concepts, and findings. Oxford University Press.

Keller, C., Visschers, V., & Siegrist, M. (2012). Affective Imagery and Acceptance of Replacing Nuclear Power Plants: Replacing Nuclear Power Plants. Risk Analysis, 32(3), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01691.x

Kim, Y., Kim, W., & Kim, M. (2014). An international comparative analysis of public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy, 66, 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.11.039

Klein, Kitty. 2003. “Narrative Construction, Cognitive Processing, and Health.” In Narrative Theory and the Cognitive Sciences, ed. David Herman. Stanford: CSLI Publications, 56–84.

Kühberger, A. (1998). The Influence of Framing on Risky Decisions: A Meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75(1), 23–55. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2781

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 363-374.

Lawlor, A., & Crow, D. (2018). Risk-Based Policy Narratives. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 843–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12270

Leifeld, P. (2013). Reconceptualizing Major Policy Change in the Advocacy Coalition Framework: A Discourse Network Analysis of German Pension Politics: Reconceptualizing Major Policy Change in the ACF. Policy Studies Journal, 41(1), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12007

Leifeld, P. (2016). Policy debates as dynamic networks: German pension politics and privatization discourse. Campus Verlag.

Leifeld, Philip (2017): Discourse Network Analysis: Policy Debates as Dynamic Networks. In J. N. Victor, A. H. Montgomery, & M. N. Lubell (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Networks (pp. 301-325). New York: Oxford University Press.

Leifeld, P. (2020). Policy Debates and Discourse Network Analysis: A Research Agenda. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.3249

Leifeld, P., & Haunss, S. (2012). Political discourse networks and the conflict over software patents in Europe: Political discourse networks. European Journal of Political Research, 51(3), 382–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02003.x

Mazmanian, D.A. & Morrell, D. (1994). The NIMBY syndrome: Facility siting and the failure of democratic discourse. In N. J. Vig & M. E. Kraft (Eds.), Environmental Policy in the 1990s: Toward a New Agenda (2nd ed., pp. 233-249). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

McBeth, M. K., Shanahan, E. A., & Jones, M. D. (2005). The Science of Storytelling: Measuring Policy Beliefs in Greater Yellowstone. Society & Natural Resources, 18(5), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920590924765

McBeth, M. K., & Lybecker, D. L. (2018). The Narrative Policy Framework, Agendas, and Sanctuary Cities: The Construction of a Public Problem: The Narrative Policy Framework, Agendas, and Sanctuary Cities. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 868–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12274

McBeth, M. K., Shanahan, E. A., Hathaway, P. L., Tigert, L. E., & Sampson, L. J. (2010). Buffalo tales: interest group policy stories in Greater Yellowstone. Policy Sciences, 43(4), 391-409.

Merry, M. K. (2016). Constructing Policy Narratives in 140 Characters or Less: The Case of Gun Policy Organizations: Policy Narratives on Twitter. Policy Studies Journal, 44(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12142

Merry, M. K. (2018). Narrative Strategies in the Gun Policy Debate: Exploring Proximity and Social Construction. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12255

Merry, M. K. (2020). Warped narratives: Distortion in the framing of gun policy. University of Michigan Press.

Miller, C. A. (2000). The Dynamics of Framing Environmental Values and Policy: Four Models of Societal Processes. Environmental Values, 9(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327100129342047

Naegler, R. (2015). With|out a Partner. The Idea of Cooperation in Higher Education Discourses. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2633108

Nagel, M., & Satoh, K. (2019). Protesting iconic megaprojects. A discourse network analysis of the evolution of the conflict over Stuttgart 21. Urban Studies, 56(8), 1681–1700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018775903

Parkhill, K. A., Pidgeon, N. F., Henwood, K. L., Simmons, P., & Venables, D. (2010). From the familiar to the extraordinary: Local residents’ perceptions of risk when living with nuclear power in the UK: Perceptions of risk when living with nuclear power in the UK. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00364.x

Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2003). Exploring the Dimensionality of Trust in Risk Regulation. Risk Analysis, 23(5), 961–972. https://doi.org/10.1111/1539-6924.00373

Rinscheid, A. (2015). Crisis, Policy Discourse, and Major Policy Change: Exploring the Role of Subsystem Polarization in Nuclear Energy Policymaking. European Policy Analysis, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.18278/epa.1.2.3

Roth, C., & Bourgine, P. (2005). Epistemic Communities: Description and Hierarchic Categorization. Mathematical Population Studies, 12(2), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08898480590931404

Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2–3), 129–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136406

Sabatier, P. A., & Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (Eds.). (1993). Policy change and learning: An advocacy coalition approach. Westview Press.

Shanahan, E. A., McBeth, M. K., Tigert, L. E., & Hathaway, P. L. (2010). From protests to litigation to YouTube: A longitudinal case study of strategic lobby tactic choice for the Buffalo Field Campaign. The Social Science Journal, 47(1), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2009.10.002

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2011). Policy Narratives and Policy Processes. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 535–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00420.x

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., McBeth, M. K., & Lane, R. R. (2013). An Angel on the Wind: How Heroic Policy Narratives Shape Policy Realities: Narrative Policy Framework. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 453–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12025

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2018a). How to conduct a Narrative Policy Framework study. The Social Science Journal, 55(3), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.12.002

Shanahan, E. A., Raile, E. D., French, K. A., & McEvoy, J. (2018b). Bounded Stories. Policy Studies Journal, 46(4), 922–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12269

Smith-Walter, A., Jones, M. D., Shanahan, E. A., & Peterson, H. (2020). The stories groups tell: campaign finance reform and the narrative networks of cultural cognition. Quality & Quantity, 54(2), 645-684

Wagner, P., & Payne, D. (2017). Trends, frames and discourse networks: Analysing the coverage of climate change in Irish newspapers. Irish Journal of Sociology, 25(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.7227/IJS.0011

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Weible, C. M., & Ingold, K. (2018). Why advocacy coalitions matter and practical insights about them. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230061739399

Weible, C. M., Ingold, K., Nohrstedt, D., Henry, A. D., & Jenkins‐Smith, H. C. (2019). Sharpening Advocacy Coalitions. Policy Studies Journal, psj.12360. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12360

Weible, C. M., Olofsson, K. L., Costie, D. P., Katz, J. M., & Heikkila, T. (2016). Enhancing Precision and Clarity in the Study of Policy Narratives: An Analysis of Climate and Air Issues in Delhi, India: Enhancing Precision and Clarity in the Study of Policy Narratives. Review of Policy Research, 33(4), 420–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12181

Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (Eds.). (2017). Theories of the policy process (Fourth edition). Westview Press.

Whitfield, S. C., Rosa, E. A., Dan, A., & Dietz, T. (2009). The Future of Nuclear Power: Value Orientations and Risk Perception. Risk Analysis, 29(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01155.x

Chapter Appendixes

Appendix A. Codebook

Tweets were manually coded by trained human coders to identify the Twitter user (actor) and narrative elements (heroes, villains, and victims). Each of these narrative elements consisted of several subtypes, which are described below.

Heroes: Those who take action with purpose to achieve or oppose a policy solution or are praised in some way.

Type of Heroes

- Business & Industry

nuc: Nuclear energy (nuclear energy, nuclear power plants, producers, operating company)

nuc_rep: Nuclear industry representative (executives, employees, staff, plant operators, i.e. people who work for nuclear power companies)

foss: Fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas)

renew: Renewable energy (wind, solar)

tech: Technology (technology, AI, smart grid, supercomputers, that is not related to nuclear energy)

nuc_tech: Advanced nuclear technology (small modular reactors, microreactors, molten salt reactors, fusion, next generation, GenIV, or technology that helps improve the safety and efficiency of nuclear power)

waste: Waste (nuclear waste)

bus_ent: Business entrepreneur (non-nuclear business)

- Environment

co2: Carbon emissions (carbon emissions, carbon, carbon dioxide, CO2, greenhouse gasses)

clim_ch: Climate change (sea-level rise, temperature change, melting ice)

phys_env: Physical environmental phenomena (earthquake, tsunami, flood, hurricane, tornado, rain, wind, polar vortex, fire)

- Government & Public Sector

policy: Policy and legislation (policy, law, legislation, regulation)

gov_rep: Government official (politician, candidate, agency representative, elected official, party official)

gov_org: Government agency (local, state, and/or federal agency, national laboratories)

- Cultural & Historical

lang: Language (language, dialect)

event: Events (historical events including Fukushima, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, the Oil Crisis)

mem: History and memory (memory, history)

- Other

advo: Advocacy (interest group, lobbyist, activist, think tank)

edu: Academia (professor, scientist, graduate student)

media: Media (newspaper, television network, journalist, anchor, blog, blogger, radio, radio host)

people: People (individuals, people, family, community)

health: Health (disease, cancer, radiation poisoning, radiation sickness)

Villains: Those who create a harm or inflict damage or pain upon a victim or, in other cases, as one who opposes the aims of the hero.

Types of Villains

- Business & Industry

nuc: Nuclear energy (nuclear energy, nuclear power plants, producers, operating company)

nuc_rep: Nuclear industry representative (executives, employees, staff, plant operators, i.e. people who work for nuclear power companies)

foss: Fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas)

renew: Renewable energy (wind, solar)

tech: Technology (technology, AI, smart grid, supercomputers, that is not related to nuclear energy)

nuc_tech: Advanced nuclear technology (small modular reactors, microreactors, molten salt reactors, fusion, next generation, GenIV, or technology that helps improve the safety and efficiency of nuclear power)

waste: Waste (nuclear waste)

bus_ent: Business entrepreneur (non-nuclear business)

- Environment

co2: Carbon emissions (carbon emissions, carbon, carbon dioxide, CO2, greenhouse gasses)

clim_ch: Climate change (sea-level rise, temperature change, melting ice)

phys_env: Physical environmental phenomena (earthquake, tsunami, flood, hurricane, tornado, rain, wind, polar vortex, fire)

- Government & Public Sector

policy: Policy and legislation (policy, law, legislation, regulation)

gov_rep: Government official (politician, candidate, agency representative, elected official, party official)

gov_org: Government agency (local, state, and/or federal agency, national laboratories)

- Cultural & Historical

lang: Language (language, dialect)

event: Events (historical events including Fukushima, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, the Oil Crisis)

mem: History and memory (memory, history)

- Other

advo: Advocacy (interest group, lobbyist, activist, think tank)

edu: Academia (professor, scientist, graduate student)

media: Media (newspaper, television network, journalist, anchor, blog, blogger, radio, radio host)

people: People (individuals, people, family, community)

health: Health (disease, cancer, radiation poisoning, radiation sickness)

Victims: Those who are harmed by a particular action or inaction.

- Human

human: Humans (individual, people, family)

child: Children (human beings under the age of 18)

community: Community (aggregate group of people, town, city)

- Wildlife & Natural Environment

env: Physical environment (soil, water, air, environment in general)

animal: Animals (animals)

- Economic

job: Jobs (jobs, employment)

tax: Taxpayers (taxpayers, citizens)

budget: Budget (household budget, fiscal budget of state)

- Cultural & Historical

lang: Language (language, dialect)

event: Events (historical events including Fukushima, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, the Oil Crisis)

mem: History and memory (memory, history)

- Other

state: The State (state, country, national interest, national security, government)

ne: Nuclear energy (nuclear energy, nuclear power plants, plant operators, industry)