Donna L. Lybecker; Mark K. McBeth; and Jessica M. Sargent

Donna L. Lybecker*, Idaho State University

Mark K. McBeth, Idaho State University

Jessica M. Sargent, Idaho State University

Abstract

Narratives concerning the working class and their relationship to climate change are important. In particular, how the narrative constructs the relationship and, within this, who communicates a narrative (the narrator) is key. That said, this is a less studied element; the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) has limited research on narrators. Subsequently, this work examines individuals’ support of narratives and narrators using an Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) survey of 435 participants. After pretesting for climate change views, the subjects chose which narrator they expected to agree with: Mechanic Pat or Organic Farmer Chris. Through randomization, subjects joined either a congruent treatment group (Mechanic Pat tells the anti-climate change narrative and Organic Farmer Chris tells the pro-climate change narrative) or an incongruent treatment group (Mechanic Pat tells the pro-climate change narrative and Organic Farmer Pat tells the anti-climate change narrative). Results indicate that before reading the narratives, climate change “devotees” (those who agree that climate change is occurring and is human-caused) thought they would agree with Organic Farmer Chris over Mechanic Pat. Whereas there was division in the climate change “skeptics” (those who disagree that climate change is real and human-caused) on the question of what narrator they thought they would agree with. Devotees significantly supported the pro-climate change working-class narrative when told by Organic Farmer Chris as compared to when Mechanic Pat told the same narrative. Further showing the power of a narrator, devotees supported the anti-working class climate change narrative more when told by Organic Farmer Chris rather than when Mechanic Pat told the same narrative. Our findings demonstrate that narrators matter and suggest that the NPF needs to consider narrators as a narrative element worthy of further study.

*Corresponding author: donnalybecker@isu.edu

To cite the chapter:

Lybecker, Donna L., Mark K. McBeth, and Jessica M. Sargent. 2022. “Agreement and Trust: In Narratives or Narrators?”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan (eds.), Montana State University Library, 91-115. doi.org/10.15788/npf4

Introduction

Support for climate change policy is building in our current world, where paralyzing political polarization is on the rise and democracy appears in decline. Worldwide, authoritarian populist agendas are succeeding and, for the past 15 years, freedoms throughout the world have declined (Freedom House, 2019, 2021). In the United States, political institutions ranging from the US Congress and Executive Branch, to the media are under attack or polarized by partisanship (Andris et al., 2015). While some contend a political middle still exists in the US population (Fiorina et al., 2010; Harrison, 2020), other data show that polarization is increasing at the individual level and political moderates are disappearing (Abramowitz, 2010; Chinni et al., 2019). Furthermore, evidence shows that individuals increasingly choose to live in communities with people who share their political views (Pew Research Center, 2014; Badger et al., 2021), see those with opposite political views as a “threat to the nation’s well-being” (Pew Research Center, 2014), and don’t want their children marry someone with opposing political views (Vavreck, 2017; Luscombe, 2020).

It is within this contentious milieu that efforts to garner wider public support for climate change policy must proceed. We are particularly interested in working-class views of climate change and climate change policy. Research shows that the impacts of climate change will disproportionately affect the working class (Islam & Winkel, 2017). Thus, understanding their perspective is vital. Scholars have found that former President Trump used fear of climate change legislation to solidify part of his working-class base. In particular, former President Trump shaped his narrative toward coal miners and in support of carbon (Meyer 2019). This, added to the fact that it is the more educated individuals who see climate change as a threat (Ballew et al., 2020; Fagan & Huang, 2019), and since the working class is less likely to hold a college degree than the middle or upper classes, this further points to the need to understand the view of the working class. In the coming years, pro-climate change groups will have to court the working class to their side. As such, we contend that understanding climate change narratives that target different groups within the working class along with who tells the story (the narrator) is crucial.

Individuals’ policy support (or lack thereof) stems in part from the narratives heard and narrators telling the story (e.g., Knackmuhs et al., 2019). When studying an issue such as climate change, undoubtedly a policy issue that will dominate the next 50 years of study among policy process theorists, it is key to examine the role of narrative and narrators. One way to achieve this is to utilize the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), an empirical and systematic approach to examining the role of narratives in the public policy process (Shanahan et al., 2018). The NPF, which is increasingly concerned about the scientific study of narrative and the role of narrative in democracy (Jones & McBeth, 2020; McBeth & Lybecker, 2018), can identify narrative polarization.

The policy narrative has become a frequently studied concept where policy often reflects competition between contending narratives (Knüpfer 2018; Foroughi et al., 2019). Previous studies show that we too often view narratives as full of emotion, bias, and belief. In this manner, narrative contrasts with scientific, rational, and evidence-based statements. For example, a climate change narrative could assert, “human caused climate change is a hoax perpetuated by liberal groups who want to end capitalism in favor of a top down and planned economy.” This narrative’s approach starkly contrasts with the evidence-based fact that 97% of scientists agree that climate change is both real and human-caused (Cook et al., 2016). The reality, however, is that even this latter proclamation frequently takes the form of a narrative with heroes (perhaps scientists), villains (perhaps powerful politicians who deny climate change), and victims (those ultimately harmed by denying climate change). Thus, the counter to the story of climate change denial often goes something like this: “Conservatives are intentionally misrepresenting the work of scientists around climate change in order to protect big businesses and this is harming current and future generations.” This style of communication clearly sets up competing narratives. Even those who use scientific facts are going to rely on narrative for their understanding. Most individuals are not able to scientifically describe and explain climate change and thus, they instead rely on narratives (with science sometimes being part of the narrative). Even scientists might use (Dahlstrom, 2014) and do use (Padian, 2018) political narratives when articulating science. Political leaders are typically not experts in the fields for which they create policy (i.e., politicians with a background in law trying to create climate change policy). Thus policy leaders, as well as laypeople, use narrative. Who these leaders are, at times, is just as important as what their stories say.

Some political scientists (Putnam, 2000) suggest that the survival of democracy in the United States depends upon reciprocal relationships gained through bridging social capital found in interactions in groups such as civic associations. Unfortunately, today much of US politics focus is on divisive online political marketing narratives rather than on bridging differences through various groups. Thus, US politics thrive not on bridged relationships but on sound bites, slogans, and narratives. In our post-fact, post-truth world, citizens are not engaging in practices that lead to bridging social capital, but instead, cling to their political identities or political tribes. In essence, citizens have become consumers who maintain brand loyalty and buy into the marketing narratives of their favorite political party or politician (McBeth & Shanahan, 2004). In such a world, as consumers, we are concerned about our lifestyle, others’ perceptions, and our identity; thus, we seek out and believe narratives that reflect our identity (Kahan et al., 2011). Furthermore, we suggest that in this polarized, marketed world, individuals are increasingly reliant upon not only the stories they hear but also the mental image they hold of the narrator. Although narratives and narrators influence an individual’s agreement or disagreement with a policy, we suggest narrators can be key to understanding policy support. As such, we suggest those influenced by the narrator mentally construct an image of this person by focusing on certain characteristics (education level, occupation, gender, religion). In addition, agreement with a narrator does not always equate to trust in the narrator. During the US presidency of Donald Trump, some of Trump’s political base argued that while they agreed with Trump’s policies, they did not necessarily trust him. White Evangelicals, for example, believed that Trump helped Evangelicals, that he shared their interests, and that they agreed with him on nearly all issues. At the same time, this very group did not find him honest or morally outstanding nor did they agree with his conduct (Pew Research Center 2020).

While we do not fully understand why some individuals place more importance on the narrator than the narrative, we know that both the constructor and construction of the narrative matters in today’s political world. Relatedly, agreement or trust in the narrator also matters, even if the narrator has no practical knowledge of the topic at hand.

Thus, we ask the following research questions:

1: Do the beliefs of respondents about human-caused climate change (devotees or skeptics) influence their preference for climate change narrators?

2a: Congruent narrator: Do respondents agree more with congruent narrators who espouse narratives congruent to their belief systems?

2b: Incongruent N=narrator: Do individuals agree more with narratives congruent with their belief systems when told by an incongruent narrator?

3a: Narrator trust and congruent narratives: Do respondents trust a congruent narrator who espouses a narrative congruent to their belief systems more than they trust an incongruent narrator who espouses a narrative congruent to their belief systems?

3b: Narrator trust and incongruent narratives: Do respondents trust a congruent narrator who espouses a narrative incongruent to their belief systems more than they trust an incongruent narrator who espouses a narrative incongruent to their belief systems?

In asking these questions, we test the NPF micro-level hypothesis of congruency/ incongruency and reexamine the NPF micro-level hypothesis of narrator trust. Following Ertas (2015), we use the NPF to explore the power of the narrator and to suggest how narratives and narrators might interact with each other. In short, we explore the power of the narrator, the identity of the narrator, and congruent and incongruent narratives in the hope of better understanding the narrative dynamics of individual support for climate change policies.

In our study, we first review the literature on emotion, beliefs, confirmation bias, and narrative, along with a review of how individuals might choose a narrator simply based on the narrator’s demographic characteristics, personal story, or political identity. We then discuss our policy issue, detail our methodology, present our results, and discuss findings.

The NPF and Theoretical Background

At the heart of the power of narrative, as asserted by the NPF, is the fundamental assumption that individual decisions rest in emotions, beliefs, and identity (Shanahan et al., 2018). Kahneman (2011), for example, refers to an individual’s quick and emotional responses as System I thinking. Instead of being rational maximizers of information, individuals seek out information that confirms their bias (Taber & Lodge, 2006). When confronted with information that contradicts their identity and beliefs, individuals experience cognitive dissonance and they seek to rationalize away their discomfort by finding information that reaffirms their identity, or better yet, they avoid cognitive dissonance causing information (Jost et al., 2013).

Defined in the NPF (Shanahan et al., 2018, p. 176) as having a plot, characters, a moral to the story, and a policy stance, the narrative serves as a heuristic, reducing complexity and reinforcing an individual’s beliefs and political identity. These characteristics (particularly reinforcing beliefs) reveal why the use of narrative is popular in today’s political arena. While fact-based, logical thinking (System II in Kahneman 2011) remains, today’s political world focuses on competing narratives with less attention paid to fact. In other words, the political arena is more likely to rely on competing narratives. With that said, many individuals do not necessarily think they are using a narrative. Instead, as Kahan et al.’s work (2012) suggests, individuals often believe they bring facts and evidence to back up their narrative while their political opponents use emotional narratives.

None of this, of course, is new. Rahn (1993) and Ahler and Sood (2018) trace the tendency of individuals to generalize about others who have different political views when making decisions to Walter Lippman who viewed this tendency as part of human cognition and a way that humans simplify the world and “see pictures in our head” (Lippman, 1922). Today, it is easy to view this generalization about those who share and do not share our political identity in the context of sociopolitical brands (Ahler & Sood, 2018). Political campaigners even use information about the shopping habits of individuals to target voters. Simmons Research (Politico Magazine, 2018), for example, provides data on the shopping habits of Republicans and Democrats showing distinctive differences between partisans in everything from automobile choice to food and media choices. These generalizations create neat packages for us to simplify reality and categorize others as either outsiders or insiders. However, as Ahler and Sood (2018) show, our generalizations are often wildly wrong. Republicans tend to overestimate the number of Democrats who are union members, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, black, atheist, or agnostic. Similarly, Democrats tend to overestimate the number of Republicans who are older than 65 or who make more than $250,000 a year. These misperceptions have consequences as partisans view the other party negatively based on these generalizations. When individuals know that the two parties are actually not that far apart on demographics, their feeling of animosity may diminish (Ahler & Sood, 2018).

The NPF does not list the narrator as an element of a policy narrative, though it is easy to conclude that who tells a story matters. In narrative terms, the narrator of a story might serve as a heuristic, used by individuals to determine their support for a narrative. The NPF has not fully ignored the power of the narrator as it offers one micro-level hypothesis (Shanahan et al., 2018, p. 235) that examines “narrator trust.” This micro-level hypothesis (tested only once) reads, “As narrator trust increases, an individual is more likely to be persuaded by the narrative” (Shanahan, 2018, p. 234). Specifically, Erstas (2015) found that individuals trusted narrators that were congruent with the individual’s pre-existing beliefs about charter schools.

The NPF hypothesis concerning congruence and incongruence, is more frequently tested and states, “As perception of congruence increases, an individual is more likely to be persuaded by the narrative” (Shanahan et al., 2018). The basic idea of this hypothesis is that individuals look for narratives that are culturally congruent with their prior cultural beliefs. Jones and Song (2014) found this empirically in their study of climate change, as did Husmann (2015) in her study of obesity. These NPF studies and others (Lybecker et al., 2013; McBeth et al., 2010; McBeth et al., 2014; McBeth et al., 2016; Lybecker et al., 2016; Clemons et al., 2012) suggest that individuals look for a narrative that fits their cultural values. In a series of studies on recycling (e.g., Lybecker et al., 2013) and support for river restoration (e.g., Lybecker et al., 2016), the authors found that a duty-based narrative (grounded in individual responsibility, business efficiency, and local empowerment) appealed to liberals and made conservatives significantly supportive of recycling and river restoration. One goal of the NPF is to help policymakers make better use of narrative (Shanahan et al., 2019; Crow & Jones, 2018). These aforementioned studies suggest that articulating narratives dealing with issues like recycling and river restoration can make these issues more congruent to conservatives. None of these studies, however, had an identified narrator. Additionally, a study involving views toward Islam and narrative congruency found that a narrative did not make those with the most entrenched political views less negative toward Islam (Clemons et al., 2020). Thus, there may well be issues where beliefs are so entrenched or sticky that congruent narratives lack power.

We contend again that narrators also matter and that an individual likely looks for a narrator he/she trusts and believes will spin a tale that is consistent with what the individual wants to hear. Building upon work by Druckman (2001), Oxley, et al. (2014) show that an individual’s evaluation of the credibility of a source is part of how a message leads to problem definition. Oxley, et al. (2014) also demonstrates there are political ideology dimensions to how individuals evaluate the credibility of a source. Furthermore, Kahan, et al.’s (2011) work on expertise suggests that individuals seek out “experts,” and “experts” are those who share similar cultural beliefs with the individual. For example, concerning climate change, someone who supports anthropocentric climate change will likely seek out the narrative of an activist or elected official who tells the scientists’ point of view, whereas a climate change skeptic might seek out an activist or politician who engages in climate change skepticism. In this regard, the individual does not have to understand climate change in either situation; instead, the individual trusts that the narrator’s narrative will be culturally consistent with their prior beliefs. Finally, the individual will likely have empathy with the narrator because the narrator is part of the individual’s in-group (Bloom, 2018).

All this suggests that individuals look for narrators to tell narratives that fit their values. Imagine an individual in the United States, who believes climate change is a hoax and that it harms working-class individuals, is watching TV when a person identified as part of the populist wing of the Republican Party responds to a question about climate change policy and its impact on the working class. This individual will likely trust the narrator and pay attention to the narrative because they want their bias confirmed. Conversely, someone who believes the opposite (that the effects of climate change harm working-class individuals and that climate change policy can help working-class individuals) will reject the narrative and narrator and may not even listen to the narrative.

Although this is today’s norm, democracies, such as the United States, assert that individuals must hear different views of political issues and must try to understand how others view the world. Thus, individuals must be able to hear divergent views from divergent narrators. Taking the given situation, a populist Republican supporter should be able to listen to the view that climate change policy can help working-class individuals. Further, the Trump supporter should listen to this view from narrators that they likely do not identify with because the individual does not fit the narrator image that the Trump supporter typically seeks out. Likewise, the Trump resistant individual should listen to the view that climate change policy can harm working-class individuals and, further, the Trump resistant should listen to this from narrators that they likely do not identify with because the person does not fit the narrator image. Unfortunately, the reality in today’s world of high political polarization is that a Trump supporter and a former member of the Trump resistance are both unlikely to listen to someone with a differing view. Perhaps the weight of hearing different views and understanding how others view the world rests on the shoulders of narrators in the form of a consensus narrative.

Policy Issue: The Working Class and Climate Change

Climate change is a commonly discussed scientific and public policy issue today. Climate change contributes to an increasing number of natural disasters (Banholzer et al., 2014; Kaplan, 2020), including more powerful hurricanes, lengthening wildfire seasons, extensive droughts, and rising numbers of refugees (Lister, 2014). The question of what causes these changes (is climate change human-caused or natural?) is at the forefront in today’s political discussions. Thus, despite many recognizing the changes, there is disagreement on causes, and thus on the best steps to address climate change.

No matter one’s perspective, moving forward necessitates understanding the divergent views and shaping inclusive discussion and action. Nowhere is this need for inclusion more evident than in the attitudes of working-class individuals. As with all groups within the United States, there is diversity within the working class. However, this group is more likely than other groups to have negative attitudes toward climate change policy (Bohr, 2014). In the United States, the former Trump Administration effectively painted climate change legislation and even scientific agreement on anthropocentric climate change as opposed to working-class interests. Former President Trump’s appeal to “Make America Great Again” partially rested on reversing climate change legislation advanced by former President Obama (Guillen & Wolff, 2017). Trump worked to deregulate industries and sell his deregulation as part of returning jobs to the working class (the beneficiaries of his policies). In particular, Trump presented the fossil fuel and coal industries as job providers to the working class (heroes), and he attested that deregulation would spur more jobs in these sectors. For example, in promoting environmental deregulation at the end of his first year in office, former President Trump declared, “For many decades, an ever-growing maze of regulations, rules, restrictions has (sic) cost our country trillions and trillions of dollars, millions of jobs, countless American factories, and devastated many industries” (Trump 2017).

The 2019 rollout of the “Green New Deal” (Friedman, 2019) by some Democrats in the US House and US Senate demonstrated the power of the Trump narrative in pushing back on other definitions of the working class and climate change. While the Green New Deal promised to link climate change policy to working-class jobs and to help specific communities harmed by the phasing out of carbon dioxide emissions, conservatives quickly pushed back accusing the plan as leading to devastating consequences for the working class (Weichert, 2019).

Nevertheless, there are other possible views of climate change policy and the working class. The working class, for instance, will likely be the most harmed by climate change, as compared to higher-income individuals, because they have fewer resources to adapt to needed changes or to move away from problems caused by climate change. In this narrative, the working class falls victim to those who deny climate change and climate change policy (Zehner, 2018). Furthermore, investments in new energy infrastructure and new technologies could well lead to significant numbers of jobs for the working class, making those who advocate such policies heroes. Finally, in this narrative, corporations who are resisting climate change policies are the villains who are harming the interests of the working class.

Research Design and Methods

We conducted this study using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (henceforth MTurk). Four hundred and thirty-five (435) participants took part in the study and received a small cash payment. MTurk is increasingly popular in social science research. Although there are worries about the generalizability of MTurk, various studies demonstrate how it is an improvement over student and convenience sampling (Buhmeister, et al. 2011). In comparing MTurk samples to student and adult convenience samples and a randomized national sample (the 2008-9 ANES Panel Survey), Berinsky and colleagues note: “MTurk samples will often be more diverse than convenience samples and will always be more diverse than student samples” (p. 12). This makes them advantageous when compared to the long lamented “college sophomore in the laboratory” (Berinsky et al., 2012, p. 12). Other concerns over MTurk include worries over data integrity (Chandler et al., 2014). Yet, studies using MTurk samples have also been able to replicate studies such as the classic Asian Disease framing experiment and others based upon more representative samples (Casler et al., 2013; Goodman et al., 2013; Holden et al., 2013).

Based on Rahn (1993) and Ahler and Sood (2018), we contend that in a polarized society, individuals increasingly identify with others they see as similar based on what Lippman (1922) again termed the “pictures in their head.” We also know that individuals are likely to empathize with another individual or a group perceived as part of his/her in-group (Bloom 2018). Thus, rather than creating two narrators that were wildly divergent in terms of political ideology (for example, a mechanic versus an environmental activist, scientist, or professor), we intentionally tried to make two narrators with similar social characteristics. In addition, given that our focus was the working class, we wanted to represent working-class individuals from both urban and rural perspectives. Our long-term research interest consists of finding a narrator that will appeal to both climate skeptics and climate devotees.

Despite what we perceived as social characteristics that minimized individual generalization toward the narrator, we predicted, based on Rahn (1993), Ahler and Sood (2018), and Bloom (2018), that respondents who did not agree that climate change is real and human-caused would prejudge Mechanic Pat as being in their in-group. We are basing this on the assumption that those who are climate change skeptics are more likely to identify with a mechanic based on data that shows that such skeptics tend to have completed less schooling and come more from the working class (Fagan & Huang, 2019). Additionally, climate change skeptics also tend to have less engagement with the natural world, and they work indoors rather than outdoors (Funk & Hefferon, 2019). Mechanics fit this classification. Conversely, we thought that respondents who agreed that climate change was both real and human-caused would view Organic Farmer Chris as being closer to their in-group and sociopolitical brand. Organic farmers are farmers of course, but the organic label signifies a certain fashion that will appeal to those who are climate change devotees who have high levels of education (Fagan & Huang, 2019). Organic food itself is almost like a fashion statement and a way of life, and those who support climate change policy are more likely to purchase organic food. At the same time, organic farmers are indeed farmers and because of this, they might appeal to the climate change skeptics because farmers in some parts of the country are part of a conservative base.

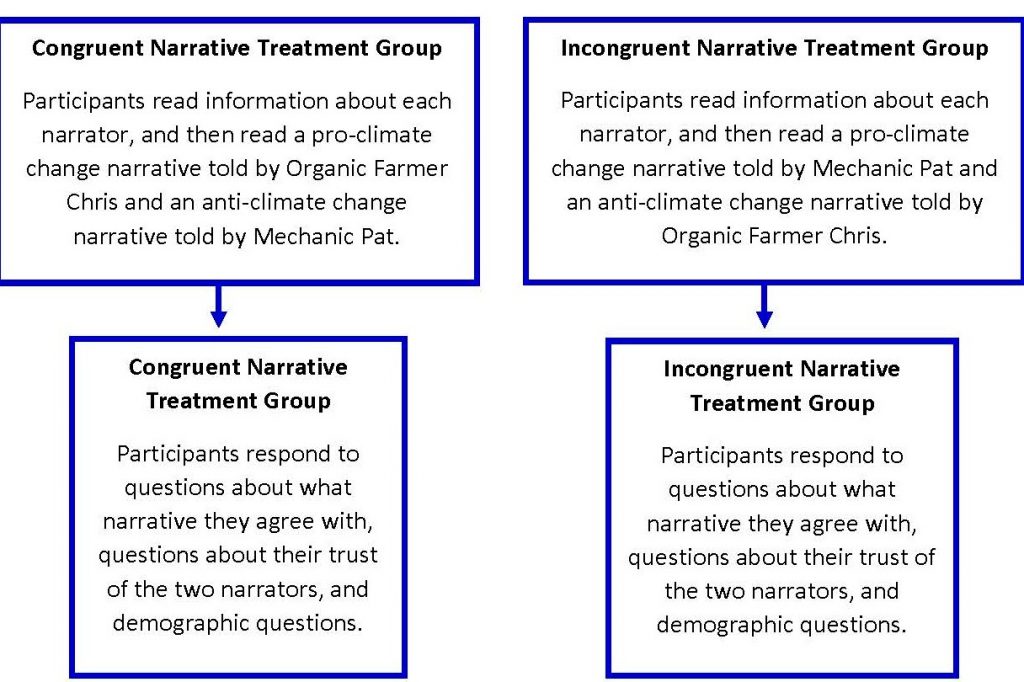

In our research design (see Figure 1 for a graphical depiction of our design), the study first asked the respondents for their level of agreement with the statement “the earth is warming mostly due to human activity” and then explained to the respondent that they would read two different narratives about climate change. The two narratives presented the respondents with two narrators, Mechanic Pat and Organic Farmer Chris. This technique, testing how individuals react to two narratives, is similar to the dueling frames literature (e.g., Rhidenour et al., 2019; Page & Duffy, 2009) and several NPF studies use dueling narratives (e.g., Lybecker et al., 2013; McBeth et al., 2010). After reading the descriptions of both narrators (see Appendix A), respondents were asked to indicate which narrator they would most likely agree with when it comes to climate change policy and its impact on working-class individuals. Our goal was to discover if respondents would clearly choose one narrator over another based on the limited information provided about each narrator. In short, we wanted to know if they would generalize (Ahler & Sood, 2018).

Again, referring to Figure 1, random assignment of participants to one of two treatments occurred. This was either a congruent treatment (where Organic Farmer Chris tells a pro-climate change narrative aimed at the working class and Mechanic Pat tells an anti-climate change narrative aimed at the working class) or an incongruent treatment (where the two narrators tell the opposite narrative compared to that of the congruent treatment). This stage of the experiment explored whether respondents would agree with the narrative, depending on who told the narrative. For example, would climate change devotees equally support a pro-climate change policy narrative told by either Mechanic Pat or by Organic Farmer Chris? In addition, would climate change skeptics equally support an anti-climate change policy narrative told by either Mechanic Pat or Organic Farmer Chris? The respondents received the narratives in random order. One narrative, based on an article by Weichert (2019), is opposed to climate legislation because the narrator believes that such policy both blames working-class individuals for the problems and harms working-class individuals. The other narrative, based on an article by Zehner (2018), argues that climate change harms working-class individuals the most and, as a result, climate change legislation will benefit working-class individuals the most. The plot of both narratives is “change is only an illusion” (Stone, 2012, p. 165), which Stone explains this way, “You always thought things were getting worse (or better). But you were wrong. Let me show you some evidence that things are in fact going in the opposite direction.” In the study’s design phase, a group of NPF scholars evaluated the narratives to ensure that each was an equal combination of narrative elements and facts. In other words, we worked to ensure that each narrative was equal in narrativity. To ensure that the narratives were equal in reading difficulty we conducted a commonly used test for reading level and reading ease. Both narratives had a Flesch-Kincaid reading grade level of 10. The Flesch Reading Ease score was 57 for the anti-climate change narrative and 59 for the pro-climate change narrative meaning that the two narratives were equally easy to read (Kincaid et al., 1975).

Figure 1. Research Design

While reading the two climate change narratives, the respondents read additional information about each narrator (See Appendix B for pro and anti-climate change narratives, rotated between narrators in the two treatments). After treatment, survey respondents reported with whom they now agree, their trust of each narrator, and demographic characteristics such as gender, political ideology, age, and income.

There are three dependent and five independent variables (Table 1)[i]. A simple contingency table and a Chi-Square calculated for dependent variables one and two. Then, because the dependent variable was dichotomous, we performed a logit regression. In addition, a Chi-Square test examined the association between who tells a story and agreement. Finally, a t-test examined differences in trust of narrators between devotees and skeptics.

Results

Research Question 1: Do the beliefs of respondents about human-caused climate change (devotees or skeptics) influence their preference for climate change narrators?

Our answer here is yes, but with skeptics more divided in their initial choice. Table 2 presents the respondents’ initial choice of what narrator they are most likely to agree with based solely on initial information. Skeptics divided evenly on the choice between Mechanic Pat (52%) and Organic Farmer Chris (48%) whereas 79% of devotees chose Organic Farmer Chris over Mechanic Pat (21%). Table 2 reveals that the chi-square was significant. The logit model in Table 3 reveals three significant relationships: climate change attitudes (devotees more likely to choose Organic Farmer Chris), gender (females are more likely to choose Organic Farmer Chris), and political ideology (liberals are more likely to choose Organic Farmer Chris).

Table 1. Variable Definitions

Dependent Variables

Pre-treatment choice of Pat or Chris

Respondents were given information about the two narrators (Appendix A), then asked to determine with which narrator they would likely agree.

Post-treatment choice of Pat or Chris

After treatment, respondents were asked with which narrator they agree.

Post-treatment trust rating of Pat and Chris

After treatment, respondents were asked to rate how much they trust each narrator on a scale of one (very untrustworthy) to five (very trustworthy).

Independent Variables

Climate change attitudes

Agreement with the statement: “The earth is warming due mainly to human activity.” A five-point Likert scale, with 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neutral), 4 (agree), 5 (strongly agree). The data were reduced to 3-point Likert scale, with those who disagree or were neutral were deemed skeptics and those who agreed were deemed devotees.

Gender

female, male, and decline to answer.

Political ideology

Five-point Likert scale, with 1 (strong conservative), 2 (conservative), 3 (moderate), 4 (liberal), 5 (very liberal).

Income

Total household income with seven categories: less than $20,000, $20,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 to $99,9999, $100,000 to $149,999, and $150,000 or more.

Age

_ Six categories: 18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65+

Table 2. Respondents Initial Choice of Pat or Chris

| Agreement | Skeptics (%) n | Devotees (%) n |

| Agree with Mechanic Pat | (52%) 72 | (21%) 62 |

| Agree with Organic Farmer Chris | (48%) 67 | (79%) 229 |

| Total | 139 | 291 |

X2 = 40.28, df = 1, p. < 0.001

Table 3. Logit Model of Respondents Initial Choice of Pat or Chris

| Variable | Estimate | Robust S.E. | Z | Wald Statistic | df | p. |

| Intercept | -1.484 | 0.735 | -2.031 | 4.123 | 1 | 0.042* |

| Climate | 1.177 | 0.246 | 4.753 | 22.594 | 1 | 0.001** |

| Gender | -0.601 | 0.235 | -2.524 | 6.368 | 1 | 0.012* |

| Ideology | 0.252 | 0.106 | 2.444 | 5.975 | 1 | 0.015* |

| Income | 0.065 | 0.078 | 0.825 | 0.680 | 1 | 0.409 |

| Age | 0.109 | 0.101 | 1.015 | 1.030 | 1 | 0.310 |

McFadden R2 = 0.10, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.16

Note. *p. <. 0.05; **p. < 0.01

Research Question 2a: Congruent narrator: Do respondents agree more with congruent narrators who espouse narratives congruent to their belief systems?

Not surprisingly, the answer is yes. Table 4 reveals the results of the congruent study where Organic Farmer Chris tells the pro-climate change working-class narrative and Mechanic Pat tells the anti-climate change working-class narrative. In this treatment, 63% of skeptics choose Mechanic Pat as the narrator with whom they agreed (as Mechanic Pat told the anti-climate change narrative). While 82% of devotees choose Organic Farmer Chris (who told the pro-climate change narrative). The Chi-Square was significant. The logit model in Table 5 produced two significant relationships with climate change attitudes: devotees and political liberals are more likely to choose Organic Farmer Chris.

Table 4. Respondents Agreement with Narrator after Treatment-Congruent Study

| Agreement | Skeptics (%) n | Devotees (%) n |

| Agree with Pat | (63%) 45 | (18%) 28 |

| Agree with Chris | (37%) 27 | (82%) 127 |

| Total | 72 | 155 |

X2 = 44.92, df =1, p. < 0.01

Table 5. Logit Model of Respondents Agreement with Narrator after Treatment-Congruent Study

| Variable | Estimate | Robust S.E. | Z | Wald

Statistic |

Df | p. |

| Intercept | -4.782 | 1.198 | 4.005 | 16.042 | 1 | 0.001** |

| Climate | 1.747 | 0.359 | 4.818 | 23.215 | 1 | 0.001** |

| Gender | 0.325 | 0.346 | 0.942 | 0.887 | 1 | 0.346 |

| Ideology | 0.434 | 0.165 | 2.8235 | 8.040 | 1 | 0.005** |

| Income | 0.168 | 0.114 | 1.373 | 1.885 | 1 | 0.170 |

| Age | 0.064 | 0.156 | 0.412 | 0.170 | 1 | 0.680 |

McFadden R2 = 0.21, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.32

Note. **p. < 0.01

Research Question 2b. Incongruent narrator: Do individuals agree more with narratives congruent with their belief systems when told by an incongruent narrator?

The answer is yes. The narrative is stronger than the narrator, but, as you will see later, the narrator does matter. Table 6 shows the results from the incongruent narrative treatment with 69% of skeptics agreeing with Organic Farmer Chris (who told the anti-climate change narrative) compared to 68% of devotees who agreed with Mechanic Pat (who in this treatment told the pro-climate change narrative). The Chi-Square was significant (X2 = 23.551, df = 1, p. < 0.001). The logit model in Table 7 produced one significant relationship where skeptics were more likely to agree with Organic Farmer Chris and the other independent variables were not significant.

Table 6. Respondents Agreement with Narrator after Treatment-Incongruent Study

| Choice | Skeptics

(%) n |

Devotees

(%) n |

| Choose Mechanic Pat | (31%) 21 | (68%) 92 |

| Choose Organic Famer Chris | (69%) 46 | (32%) 44 |

| Total | 67 | 136 |

X2 = 23.551, df = 1, p. < 0.001

Table 7. Logit Model of Respondents Agreement After Treatment-Incongruent Study

| Variable | Estimate | Robust S.E. |

Z |

Wald

Statistic |

df |

p. |

| Intercept | 2.990 | 0.990 | 2.963 | 8.780 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Climate | -1.287 | 0.347 | -3.734 | 13.940 | 1 | 0.001** |

| Gender | 0.012 | 0.319 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.970 |

| Ideology | -0.245 | 0.141 | -1.771 | 3.135 | 1 | 0.077 |

| Income | -0.064 | 0.115 | 0.605 | 0.366 | 1 | 0.545 |

| Age | -0.008 | 0.143 | 0.056 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.955 |

McFadden R2 = 0 .10, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.17

Note. **p. < 0.01

Table 8 provides an analysis of agreement with either the pro-climate change or anti-climate change narrative and the narrator who tells the story. While congruent narratives are most important to individuals, narrators do matter. Table 8 reveals that both devotees had a higher percentage of agreement with Organic Farmer Chris over Mechanic Pat regardless of the narrative told. For example, among devotees, when Organic Farmer Chris tells the pro-climate change story, 82% of devotees agree with Organic Farmer Chris compared to only 68% when Mechanic Pat tells the story (this was statistically significant). Similarly with devotees, when Organic Farmer Chris tells the anti-climate change story, 32% agree with Organic Farmer Chris compared to only 18% when Mechanic Pat tells the same story (this was statistically significant). Among skeptics, when Organic Farmer Chris tells the pro-climate change story, 37% of skeptics agree with Organic Farmer Chris compared to 31% who agree with Mechanic Pat when he tells the story (this was not statistically significant). Finally, when Organic Farmer Chris tells the anti-climate change story, 69% of skeptics agree with him versus only 63% who agree with Mechanic Pat when he tells the same story (this was not statistically significant). We conclude that while devotees look for a congruent narrative, the narrator Organic Farmer Chris influences them.

Research Question 3a: Narrator trust and congruent narratives: Do respondents trust a congruent narrator who espouses a narrative congruent to their belief systems more than they trust an incongruent narrator who espouses a narrative congruent to their belief systems?

This answer is surprisingly no. Table 9 provides data on the trust of the narrator broken out by devotee and skeptic. Among devotees, there was no statistically significant difference between the trust of Mechanic Pat or Organic Farmer Chris when either told the pro-climate change narrative. Similarly, there was no significant difference in trust among skeptics when either Mechanic Pat (3.69) or Organic Farmer Chris (3.65) told the anti-climate change narrative.

Research Question 3b: Narrator trust and incongruent narratives: Do respondents trust a congruent narrator who espouses a narrative incongruent to their belief systems more than they trust an incongruent narrator who espouses a narrative incongruent to their belief systems?

The answer is yes and no (see Table 9). Devotees were significantly different in their trust of Organic Farmer Chris and Mechanic Pat when they told the anti-climate change narrative. When Mechanic Pat tells the story, devotees give him an average trust rating of 3.19 compared to giving Organic Farmer Chris an average trust rating of 3.50 when he tells the same anti-climate change narrative (t = 2.66, df = 290, p. 0.0085). Skeptics, on the other hand, did have a higher average trust rating of Mechanic Pat (3.69) compared to Organic Farmer Chris (3.45) when either tells the pro-climate narrative, but the difference was not statistically significant (t = 1.606, df = 138; p. .1106).

Table 8. Agreement with Narrative of Devotee or Skeptic Based on Who Tells the Story

| Devotee agreement with the pro-climate change narrative

When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story is 82%. When Mechanic Pat tells the story is 68%. X2 = 7.94, df =1, p. 0.004 (significant)

Devotee agreement with the anti-climate change narrative When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story is 32%. When Mechanic Pat tells the story is 18%. X2 = 7.94, df = 1, p. 0.004 (significant)

Skeptic agreement with the pro-climate change narrative When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story is 37% When Mechanic Pat tells the story is 31% X2 = .5818, df =1, p. 0.4455 (not significant)

Skeptic agreement with the anti-climate change narrative When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story is 69% When Mechanic Pat tells the story is 63% X2 = .5818, df =1, p. 0.4455 (not significant) |

Note. Count data led to a Chi-Square calculation. Data in percentages are for presentation purposes.

Table 9. Trust of Devotee or Skeptic Based on Who tells the Story

| Devotee Trust of Narrator Telling the Pro-Climate Change Narrative

Mean SD n When Mechanic Pat tells the story 4.00 0.678 137 When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story 4.03 0.704 156 t = 0.3703

Devotee Trust of Narrator Telling the Anti-Climate Change Narrative Mean SD n When Mechanic Pat tells the story 3.19 0.940 155 When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story 3.50 1.058 137 t = 2.66 p. 0.0085**

Skeptic Trust of Narrator Telling the Pro-Climate Change Narrative Mean SD n When Mechanic Pat tells the story 3.69 0.821 70 When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story 3.45 0.943 70 t = 1.606 p. 0.1106

Skeptic Trust of Narrator Telling the Anti-Climate Change Narrative Mean SD n When Mechanic Pat tells the story 3.69 0.821 70 When Organic Farmer Chris tells the story 3.65 1.048 68 t = .2500 p. 0.8030 |

Note. ** p. < 0.01

Discussion

We find that, prior to reading a narrative, devotees initially favor Organic Farmer Chris overwhelmingly (79%). This highlights the power of identifying with the in-group (Ahler & Sood, 2018) and how the pictures in our head (Lippmann, 1922) influence our political decisions in our post-fact world. Surprisingly, skeptics were initially divided between Mechanic Pat and Organic Farmer Chris when choosing the person with whom they were more likely to agree. We had expected skeptics to identify more with Mechanic Pat compared to Organic Farmer Chris, but that was not necessarily the case even in the initial choice. Organic Farmer Chris is a narrator that has broad appeal to both skeptics and devotees. This is a critical finding and one that we discuss in more detail later. Gender also plays a role, as women were more likely to choose Organic Farmer Chris. This data provides some initial evidence for the NPF about the power of the narrator.

When narratives entered into the scenario, not surprisingly, there were shifts in agreement from the initial choice of with which narrator the respondent thought they would agree. This provides backing to the NPF congruency hypothesis (Shanahan et al., 2018). The congruent treatment played out mainly as expected; skeptics agreed with Mechanic Pat telling the anti-climate change story and devotees agreed with Organic Farmer Chris telling the pro-climate change story. This shows the power of narratives that are congruent with an individual’s pre-existing beliefs, and the findings are consistent with other NPF studies (Lybecker et al., 2013, Clemons et al., 2012).

Similarly, results were not surprising in the incongruent treatment as skeptics agreed with Organic Farmer Chris when he told the anti-climate change story and devotees agreed with Mechanic Pat when he told the pro-climate change story. In this regard, the findings in both the congruent and incongruent treatments show the power of the narrative over the narrator in that respondents chose the predicted narrative based on their pre-existing beliefs about climate change. Yet, once again, there is nuance in the data, and this provides important evidence of the power of the narrator. Specifically, devotees significantly agree more with Organic Farmer Chris when he tells the pro-climate change story (in the congruent treatment) than they do with Mechanic Pat when he tells the story (in the incongruent treatment). Narrators certainly matter and the NPF should pursue more research in the area of the narrator’s power.

We were also surprised that skeptics were no more likely to agree with Mechanic Pat compared to Organic Farmer Chris regardless of the narrative told (refer to Table 9). We again expected that skeptics would identify with—and thus be more likely to agree with—Mechanic Pat. Based on the data, this was not the case. Perhaps, this is again simply a result of credibility as Chris is an organic farmer who works the land but still maintains ties with a family farm, and though educated in an elite school (Ohio State University), he was also educated in a public school in a more traditional Midwestern state (that voted for Trump in 2016). Conversely, we were not surprised that devotees always agreed more with Organic Farmer Chris than with Mechanic Pat regardless of the story told. However, somewhat surprising, Devotee agreement with Organic Farmer Chris when he tells the anti-climate change narrative is quite high (32%), showing the power of the narrator when it comes to agreement. Devotees, it seems, could listen to Organic Farmer Chris to some degree while they had a much more difficult time listening to Mechanic Pat. There is intriguing data for future NPF research in Table 9 demonstrating the power of the narrator.

Our study advances previous NPF research on the trust of the narrator (Erstas, 2015). In our data, when it comes to the trust of the narrator, devotees surprisingly trusted Mechanic Pat and Organic Farmer Chris equally when both told the pro-climate change narrative. This is surprising since devotees had a significantly higher agreement with the pro-climate change narrative when told by Organic Farmer Chris and not Mechanic Pat. This, of course, shows the power of the narrative and in this case, devotees seem to trust the narrative regardless of the narrator. Yet, devotees trusted Organic Farmer Chris significantly more than Mechanic Pat when telling the anti-climate change narrative. We would assume instead that the power of the narrative would mean that devotees would equally distrust the narrator of an anti-climate change narrative, but that is not the case. Thus, for some respondents, the level of trust and agreement appear to be separate elements, while for others trust and agreement intertwine. This suggests that some individuals are more concerned about their level of trust for the narrator when deciding on an agreement, while others are less concerned about this.

Conclusion

What does this all mean in terms of our questions about the interplay of narrators and narratives and what does it mean for public policy process theory and for future NPF studies? We contend that the power of the narrator, Organic Farmer Chris, is particularly intriguing. As a flip side to this, contrary to expectations, skeptics did not overwhelmingly identify with Mechanic Pat. Organic Farmer Chris’ power as a narrator with both Devotees and Skeptics suggest that a narrator character like an organic farmer is a preferred narrator to tell the working class pro-climate change narrative, as skeptics were equally likely to listen to Organic Farmer Chris as to Mechanic Pat (refer to Table 9). We know that identity matters (Ahler & Sood, 2018), we intentionally choose the organic farmer as a narrator whose identity might build a bridge between skeptics and devotees. We conjecture that an organic farmer is someone who skeptics can identify with as a narrator even when that narrator is telling a pro-climate change story. This dual identity is crucial in a narrator who might bridge between polarized groups. Importantly, a farmer invokes pastoral images as well as the image of the family farm, which appeals to rural individuals who are skeptical of climate change. The fact that the farmer is an organic farmer might make him equally appealing to climate change supporters. While this study establishes that narrators matter, we would be interested in the impact of a narrator like Organic Farmer Chris telling a narrative more intentionally constructed to reach a climate change skeptic. Our findings as least partially confirm our original idea that individuals base their beliefs on the pictures in their heads. Since individuals base their beliefs on mental images and narratives, political groups should capitalize on those tendencies by providing trustworthy and relatable narratives and narrators.

Previous research (e.g., Lybecker et al., 2013) asserts that narratives serve as a heuristic reducing uncertainty, and that while narratives can certainly divide individuals and groups, they can also build bridges between opposing groups (Lybecker et al., 2016; McBeth et al., 2017). Based on previous research (McBeth et al., 2017; McBeth et al., 2014; Lybecker et al., 2013), we ask how skeptics might react to a working-class climate narrative that (1) uses science but also reduces the abstract nature of climate change, (2) effectively uses the right heroes, (3) avoids using a villain, (4) uses effective victims, and (5) is told by Organic Farmer Chris.

Narratives can build bridges to conservatives in environmental issues by including heroic characterizations of individual responsibility and concern for business (e.g., Lybecker et al., 2013). Narratives that do not use villains and rather use sympathetic victims (McBeth et al., 2017) and that also use concrete real-life examples instead of abstract scientific ones are also more powerful in building these bridges (McBeth et al., 2014). However, this previous research misses a narrator who, when using such a narrative, can enhance the power of the narrative.

Overall, the current research shows the potential power of a narrator in strengthening democracy through building bridges between pro-climate change advocates and those more skeptical of climate change. The NPF has a role in helping practitioners better use narratives (Crow & Jones 2018; Shanahan et al., 2019) and use narratives and narrators to build bridges between these groups is particularly crucial in securing working-class support for climate change policy. More research into the narrator’s role in reducing polarization between groups would add greatly to the NPF and to the NPF’s role in furthering both democracy and science (Jones & McBeth 2020).

References

Abramowitz, Alan. 2010 The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ahler, Douglas J., and Gaurav Sood. 2018. “The Parties in our Heads: Misperceptions About Party Composition and Their Consequences.” The Journal of Politics 80(3): 964-981.

Andris, C., Lee, D., Hamilton, M.J., Martino, M., Gunning, C.E. and Selden, J.A., 2015. “The Rise of Partisanship and Super-cooperators in the U.S. House of Representatives.” PLOSOne 10(4):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123507.

Badger, Emily, Kevin Quealy and Josh Katz. 2021. “A Close-Up Picture of Partisan Segregation, Among 180 Million Voters.” The New York Times March 17 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/17/upshot/partisan-segregation-maps.html (Accessed May 11, 2021).

Ballew, Matthew. T., Adam R. Pearson, Matthew H. Goldberg, M. H., Seth A. Rosenthal, and Anthony Leiserowitz. (2020). “Does Socioeconomic Status Moderate the Political Divide on Climate Change? The Roles of Education, Income, and Individualism.” Global Environmental Change 60: 102024.

Banholzer, Sandr., James Kossin, and Simon Donner. 2014. “The Impact of Climate Change on Natural Disasters.” In Reducing Disaster: Early Warning Systems for Climate Change (pp. 21-49).Springer, Dordrecht.

Bazelon, Emily. 2014. Sticks and Stones: Defeating the Culture of Bullying and Rediscovering the Power of Character and Empathy. Random House: New York, NY.

Berinsky, Adam J., Gregory A. Huber, and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2012. “Using Mechanical Turk as a Subject Recruitment Tool for Experimental Research.” Political Analysis 20: 351-68.

Bloom, Paul. 2017. “Empathy and its Discontents.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21(1): 24- 31.

Bohr, Jeremiah. 2014. “Public Views on the Dangers and Importance of Climate Change: Predicting Climate Change Beliefs in the United States through Income Moderated by Party Identification.” Climatic Change 126 (1-2): 217-227.

Buhmeister, Michael D., Tracy Kwang, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2011. “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New Source of Inexpensive, Yet High-Quality, Data?” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6: 3-5.

Casler, Krista, Lydia Bickel, and Elizabeth Hackett. 2013. “Separate but Equal? A Comparison of Participants and Data Gathered Via Amazon’s Mturk, Social Media, and Face-to-Face Behavioral Testing.” Computers in Human Behavior 29: 2156-60.

Chandler, Jesse, Pam Mueller, and Gabriele Paolacci. 2014. “Nonnaïveté among Amazon Mechanical Turk Workers: Consequences and Solutions for Behavioral Researchers.” Behavior Research Methods 46: 112-30.

Chinni, Dante, Aaron Zitnerm, and Brian McGill. 2019. “The Disappearing Political Center: In More Places, Elections Aren’t Close,” The Wall Street Journal (September 20, 2019). https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-disappearing-political-center-in-more-places-elections-arent-close-11568984400. (Accessed May 11, 2021).

Clemons, Randy S., Mark K. McBeth, Rolf Peterson, and Carl Palmer. 2020. “The Narrative Policy Framework and Sticky Beliefs: An Experiment Studying Islamophobia.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 27(3): 472-500.

Clemons, Randy S., Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth Kusko. 2012. “Understanding the Role of Policy Narratives and the Public Policy Arena: Obesity as a Lesson in Public Policy Development.” World Medical & Health Policy 4 (2): 1-26.

Cook, John. Naomi Oreskes, Peter T Doran, William R L Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Ed W. Maibach, J. Stuart Carlton, Stephan Lewandowsky, Andrew G. Skuce, Sarah A. Green, Dana Nuccitelli, Peter Jacobs, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Rob Painting and Ken Rice. 2016. “Consensus on Consensus: A Synthesis of Consensus Estimates on Human-Caused Global Warming.” Environmental Research Letters 11(4): DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

Crow, Deserai and Michael D. Jones. 2018. “A Guide to Telling Good Stories that Affect Policy Change.” Policy & Politics 46(2): 217-234.

Dahlstrom, Michael F. 2014. “Using Narratives and Storytelling to Communicate Science with Nonexpert Audiences.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (September 16), Supplement 4: 13614-13620. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1320645111.

Druckman, James N. 2001. “On the Limits of Framing Effects: Who can Frame?” Journal of Politics 63(4): 1041-1066.

Ertas, Nevbahar. 2015. “Policy Narratives and Public Opinion Concerning Charter Schools.” Politics & Policy 43(3): 426-451.

Fiorina, Morris P, Samuel J. Abrams, and Jeremy C. Pope. 2010. Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, 3rd edition. New York: Longman.

Freedom House. 2021, “Nations in Transit 2021: The Antidemocratic Turn.” https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2021/antidemocratic-turn. (Accessed May 1, 2021).

Freedom House. 2019. “Democracy in Retreat.” https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Feb2019_FH_FITW_2019_Report_ForWeb-compressed.pdf. (accessed October 1, 2020).

Friedman, Lisa. 2019. “What Is the Green New Deal? A Climate Proposal, Explained.” New York Times. February 21, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/climate/green-new-deal-questions-answers.html (accessed April 17, 2020).

Foroughi, Hamid, Gabriel Yiannis, and Fotaki, Marianna. 2019. “Leadership in a Post-Truth Era: A New Narrative Disorder?” Leadership 15 (2): 135-151. DOI:10.1177/1742715019835369.

Fagan, Moira, and Christine Huang. 2019. “A Look at How People Around the World View Climate Change.” April 18. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/18/a-look-at-how-people-around-the-world-view-climate-change/ (accessed August 23, 2020).

Funk, Cary and Meg Hefferon. 2019. “US Public Views on Climate Change and Energy.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/11/25/u-s-public-views-on-climate-and-energy/ (accessed October 2, 2020).

Gallup. 2020.“Presidential Approval Ratings – Donald Trump.” https://news.gallup.com/poll/203198/presidential-approval-ratings-donald-trump.aspx (Accessed August 23, 2020).

Goodman, Joseph K., Cynthia E. Kryder, and Amar Cheema. 2013. “Data Collection in a Flat World: Strengths and Weaknesses of Mechanical Turk Samples.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26: 213-24.

Guillen, Alex and Eric Wolff. 2017. “5 Big Things that Trump is Doing to Reverse Obama’s Climate Change Policies.” Politico, October 10, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/10/10/trump-obama-climate-clean-energy-243655 (accessed April 17, 2020).

Harrison, Kellie L. 2020. “The Forgotten Center: An Analysis into the Disappearing Moderate in a Climate of Increasing Political Polarization.” Inquiries Journal 12(9). http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1796 (accessed February 1, 2021).

Holden, Christopher J., Trevor Dennie, and Adam D. Hicks. 2013. “Assessing the Reliability of the M5-120 on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.” Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1749-54.

Husmann, M.A., 2015. “Social Constructions of Obesity Target Population: An Empirical Look at Obesity Policy Narratives. Policy Sciences 48(4): 415-442.

Islam, S. Nazrul and John Winkel. 2017. “Climate Change and Social Inequality.” United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf (accessed August 23, 2020).

Jost, John T., Erin P. Hennes, and Howard Lavine. 2013. “Hot” Political Cognition: Its Self- Group-, and System-Serving Purposes. In (pp. 851-875. Oxford Library of Psychology The Oxford Handbook of Social Cognition. Edited by D.E. Carlston. Oxford University Press.

Lister, Matthew. 2014. “Climate Change Refugees.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 17(5): 618-634.

James, Gareth, Daniela Witten, Trevor Hastie, and Robert Tibshirani. 2017. An Introduction to Statistical Learning, 8th edition, Springer Science.

Jones, Michael D. and Mark K. McBeth. 2020. “Narrative in the Time of Trump: Is the Narrative Policy Framework Good Enough to be Relevant?” Administrative Theory & Praxis April 11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1750211 (accessed February 1, 2021).

Kahan, Dan M., Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, Donald Braman, and Gregory Mandel. 2012. “The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks.” Nature Climate Change 2(10): 732-735.

Kahan, Dan M., Hank Jenkins‐Smith, and Donald Braman. 2011. “Cultural Cognition of Scientific Consensus.” Journal of Risk Research 14(2): 147-174.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Macmillan.

Kincaid, J. Peter, Robert P. Fishburne Jr, Richard L. Rogers, and Brad S. Chissom. 1975. “Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel.” Institute for Simulation and Training 56. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=istlibrary (accessed April 19, 2020).

Knackmuhs, Eric, James Farmer, and Doug Knapp. 2019. “The Relationship Between Narratives, Wildlife Value Orientations, Attitudes, and Policy Preferences.” Society & Natural Resources 32(3): 303-321.

Lippmann, Walter. 1922. Public Opinion. London: Routledge.

Luscombe, Belinda. 2020. “Would You Date Someone With Different Political Beliefs? Here’s What a Survey of 5,000 Single People Revealed.” Time Magazine. (October 7, 2020) https://time.com/5896607/dating-political-ideology/ (accessed February 1, 2021).

Lybecker, Donna L., Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth Kusko. 2013. “Trash or Treasure: Recycling Narratives and Reducing Political Polarisation.” Environmental Politics 22(2): 312-332.

Lybecker, Donna L., Mark K. McBeth, and James W. Stoutenborough. 2016. “Do We Understand What the Public Hears? Stakeholders’ Preferred Communication Choices for Decision Makers when Discussing River Issues with the Public.” Review of Policy Research 33(4): 376-392.

Kahan, Daniel M., Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, Donald Braman, and Gregory Mandel. 2012. “The Polarizing Impact of Science Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks.” Nature Climate Change 2: 732–735.

Kahan, Daniel M. Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Donald Braman. 2011. “Cultural Cognition of Scientific Consensus.” Journal of Risk Research 14: 1-28.

Kaplan, Sarah. 2020. “The Undeniable Link Between Weather Disasters and Climate Change.” The Washington Post, October 22, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2020/10/22/climate-curious-disasters-climate-change/ (accessed May 1, 2021).

Knüofer, Curd Benjamin. 2018. “Diverging Projections of Reality: Amplified Frame Competition via Distinct Modes of Journalistic Production,” Journalism Studies 19(4): 594-611.

McBeth, Mark K and Donna L. Lybecker. 2018. “The Narrative Policy Framework, Agendas, and Sanctuary Cities: The Construction of a Public Problem.” Policy Studies Journal 46(4): 868-893.

McBeth, Mark K., Donna L. Lybecker, James W. Stoutenborough, Katrina Running, and Sarah Davis. 2017. “Content Matters: Stakeholder Assessment of River Stories or River Science.” Public Policy and Administration 32(3): 175-196.

McBeth, Mark K., Donna L. Lybecker, and James W. Stoutenborough. 2016. “Do Stakeholders Analyze their Audience: The Communication Switch and Stakeholder Personal versus Public Communication Choices” Policy Sciences 49(4): 421-444.

McBeth, Mark K., Donna L. Lybecker, and Maria A. Husmann. 2014. “The Narrative Policy Framework and the Practitioner: The Case of Recycling Policy.” Chapter 3 (pp. 45-68) in The Science of Stories: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework in Public Policy Analysis. Edited by Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. New York: Palgrave-McMillian.

McBeth, Mark K., Donna L. Lybecker, and Kacee A. Garner. 2010. “The Story of Good Citizenship: Framing Public Policy in the Context of Duty-Based versus Engaged Citizenship.” Politics & Policy 38(1): 1-23.

McBeth, Mark K. and Elizabeth A. Shanahan. 2004. “Public Opinion for Sale: The Role of Policy Marketers in Greater Yellowstone Policy Conflict.” Policy Sciences 37(3): 319-338.

Meyer, Robinson. 2019. “Trump is not a Climate Change Denier, He’s Worse.” The Atlantic November 5. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/11/ideology-behind-donald-trumps-paris-withdrawal/601462/ (accessed August 23, 2020).

Najale, Maxine and Robert P. Jones. 2019. “American Democracy in Crisis: The Fate of Pluralism in a Divided Nation.” PRRI December 7. https://www.prri.org/research/american-democracy-in-crisis-the-fate-of-pluralism-in-a-divided-nation/ (Accessed September 1, 2020).

Oxley, Douglas R., Arnold Vedlitz, and B. Dan Wood. 2014. “The Effect of Persuasive Messages on Policy Problem Recognition.” Policy Studies Journal 42(2): 252-268.

Padian, Kevin Padian. 2018. “Narrative and ‘Anti-narrative’ in Science: How Scientists Tell Stories, and Don’t, Integrative and Comparative Biology 58(6): 1224–1234, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icy038.

Page, Janis. T. and Margaret E. Duffy. 2009. “A Battle of Visions: Dueling Images of Morality in US Political Campaign TV Ads.” Communication, Culture & Critique 2(1): 110-135.

Pew Research Center. 2020. “White Evangelicals See Trump as Fighting for their Beliefs, Though Many Have Mixed Feelings About His Personal Conduct.” March 12, https://www.pewforum.org/2020/03/12/white-evangelicals-see-trump-as-fighting-for-their-beliefs-though-many-have-mixed-feelings-about-his-personal-conduct/ (accessed March 21, 2020).

Pew Research Center. 2014. “Political Polarization in the American Public.” June 12. https://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/ (accessed August 2, 2020).

Politico Magazine. 2018. “Do You Eat Republican Cheese? The Two Americas, A Snapshot in Brands.” November/ December. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/11/02/brands-preferred-democrats-republicans-221912 (accessed March 20, 2020).

Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rahn, Wendy M. 1993. “The Role of Partisan Stereotypes in Information Processing about Political Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37(2): 472-496.

Rhidenour, Kayla. B., Ashley, Barrett, and Kate Blackburn. 2019. “Heroes or Health Victims?: Exploring how the Elite Media Frames Veterans on Veterans Day.” Health Communication 34(4): 371-382.

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Ann Marie Reinhold, Eric D. Raile, Geoffrey C. Poole, Richard C. Ready, Clemente Izurieta, Jamie McEvoy, Nicolas T. Bergmann, and Henry King. 2020. “Characters Matter: How Narratives Shape Affective Responses to Risk Communication.” PLOSOne 14(1): https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?type=printable&id=10.1371/journal.pone.0225968 (accessed February 1, 2021).

Shanahan, Elizabeth, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Claudio Radaelli. 2018. “The Narrative Policy Framework” (Chapter 5, pp. 173-213) in Theories of the Policy Process, 4th edition (Chris M Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, eds). Boulder: Westview Press.

Stone, Deborah. 2012. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd edition. New York: WW Norton.

Taber, Charles S., and Martin Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 755-769.

Trump, Donald. 2017. Remarks by President Trump on Deregulation. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-deregulation/.

Weichert, Brandon J. 2019. “The Green New Deal is About Punishing Working-Class. Americans.” The American Spectator, February 11. https://spectator.org/the-green-new-deal-is-about-punishing-working-class-americans/ (accessed April 16, 2020).

Vavreck, Lynn. 2017. “A Measure of Identity: Are You Wedded to Your Political Party?” January 31. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/upshot/are-you-married-to-your-party.html.

Zehner, Harry. 2018. “Opinion: It’s Time for a New Climate Change Narrative.” The Daily Campus, December 3. https://dailycampus.com/stories/2018/12/3/its-time-for-a-new-climate-change-narrative (accessed April 16, 2020).

[i] A Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis (James, et al., 2017) of multi-collinearity showed only very slight bias in the model using the five independent variables. The average VIF for the congruent narrative treatment model was 1.14. In the incongruent narrative treatment model, the VIF average was 1.08.

Chapter Appendixes

Appendix A. Initial Biographies of the Two Narrators

Mechanic: Pat learned the mechanics trade from classes in high school and at the local community college in Georgia. He apprenticed for a number of years prior to buying his own garage.

Organic farmer: Chris earned a bachelor’s degree in agricultural systems management from The Ohio State University. Upon graduation, Chris returned to his family’s farm, taking over management and ultimately switching the production to be organic.

Appendix B. Conflicting Climate Change Narratives and Additional Narrator Information

Additional Biography for Each Narrator

Pat is a mechanic from Georgia. He considers himself and his family solid working class. He believes we all need to have a voice concerning what is important, thus he makes a point to be a part of discussions about the future through groups such as the Kiwanis. Pat’s views are based on his personal experience as a mechanic from a mid-sized city in the southern United States.

Chris is an organic farmer from Ohio. He was a first-generation college student who worked his way through school in order to gain a better understanding of farm management. Seventeen years ago, Chris convinced his family to convert the 135-acre family farm, started by his great grandfather, to organics. He believed organic farming would be better for the land and the family living on the land and would allow for greater profits. Chris is connected to his community and is concerned about what the future may hold for family farms.

Anti-Climate Change Narrative

There was a time when laws passed by the US government aimed to benefit working people. However, today, rich globalists and their politician friends like to say they help working people with climate change policies. In reality, they are working against working people. Climate change promoters too often cast the blame for ‘climate problems’ on struggling working families. Elites view the working class as greedy polluters, but working people have to rely on petroleum and coal to take care of their families. The rich can ask us to drive electric cars, but only they can afford to do so. The United States would not be the first country to attempt to create a so-called “Green” economy. Just look at Spain. Spain tried and the results were economic ruin. According to economists, new climate change laws in Spain eliminated two jobs for every green job created. Plus, the green jobs were higher-skilled jobs filled by more-educated workers. The costs are always felt most by the already struggling working class.

Luckily, we have politicians who fight for coal miners, mechanics, farmers, and factory workers and want to end climate change policies. To protect hard-working citizens, we must ensure that wealthy climate change advocates do not continue to fool working people into believing that green jobs will help them. I oppose climate change laws that harm working people.

Pro-Climate Change Narrative

There was a time when both political parties supported environmental laws that helped working people. Working people knew the laws would protect them and their families from polluting companies. Sadly, today, many people wrongly say climate change laws are going to harm working people. It seems companies and their politician friends use the fear of job loss to create opposition. Working people are hurt the most by climate change. Climate changes that we see could ruin the economy and jobs will move to cooler climates. I cannot afford to move my family to a cooler location. The current presidential administration released a study where they warned that climate change is harming the US economy. Digging into this, I learned that the 2017 droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes in the United States led to $300 billion of damage. And, the study says, it is the working people that are most harmed by this damage.

Luckily, we have politicians who fight for climate change laws to help working people. Using more renewable energy will create new jobs. Even today, the solar industry creates as many jobs as the fossil fuel industry. We need to work to ensure that companies and politicians do not continue to fool working people into believing that climate change laws are harmful to working people. I support climate change laws that help working-class people.