Kathleen Colville and Melissa K. Merry

Kathleen Colville*, North Carolina State University, North Carolina Institute of Medicine

Melissa K. Merry, University of Louisville

Abstract

Kentucky’s proposed Medicaid reforms, initiated in 2016 and blocked in federal court in 2018 and again in 2019, elicited an extraordinary volume of public input on the value of Medicaid (publicly-funded health insurance for low-income individuals). Personal statements from current and former Medicaid consumers, through written comments submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, offer insights into the strategies employed by a segment of the public that contributes infrequently to policy debates. Through a combination of manual and automated content analysis of a random sample of 1100 public comments, we analyze the policy narratives of participants, examining how narrative and non-narrative elements varied depending on commenters’ relationship to Medicaid consumers. Nearly all comments met (and most exceeded) the threshold for a policy narrative, while relatively few comments drew on research-based content typically considered privileged in the rule-making process. Further, these narrative elements cohered in distinct storylines from current and past Medicaid consumers and from those who identified as service providers. This research underscores the importance of narratives as sources of evidence in regulatory processes and suggests that public comments are fertile ground for research using the Narrative Policy Framework. This work also illuminates bottom-up narrative construction, a process thus far overlooked in micro-level research presuming that citizens are passive recipients of narratives, rather than producers themselves. For future work examining micro-level narrative production, we identify important considerations, including the role of narrator trust, audience, forms of evidence, setting, and the interaction between the meso and micro levels.

*Corresponding author: kacolvil@ncsu.edu

To cite the chapter: Colville, Kathleen, and Melissa K. Merry. 2022. “Speaking from Experience: Medicaid Consumers as Policy Storytellers”, in Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Elizabeth A. Shanahan(eds.), Montana State University Library, 138-165. doi.org/10.15788/npf6

Introduction

From June 2016 to August 2018, interested individuals submitted over 16,000 public comments to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on the Kentucky HEALTH (Helping to Engage and Achieve Long-Term Health) Section 1115 Medicaid waiver. States seeking to try new approaches to administering Medicaid funds submit Section 1115 waiver proposals for approval by CMS, provided that these approaches are budget neutral and are aligned with Medicaid objectives of access to healthcare for low-income individuals (Hinton et al., 2019). Affordable Care Act (ACA) rules require formal solicitation of public comment to state administrations when a Section 1115 waiver is in development, and again after the proposal has been submitted to CMS (Centers, n.d.). The extraordinary volume of public comments on Kentucky HEALTH reflects the input of many different constituencies. Importantly, these comments offer researchers the opportunity to study the political activity of Medicaid consumers[1] and their opinions about the experience and direction of this program, as expressed in their own words. These comments illuminate how consumers use policy narratives not only to articulate and support their policy preferences but also to establish themselves as legitimate commenters on policy and as deserving recipients of public benefits.

With few exceptions, people who use Medicaid for their health insurance are categorically eligible for the program due to their incomes being near or below the federal poverty level (FPL). Researchers note that the political activity of low-income individuals is often suppressed or attenuated for a variety of reasons, including lower levels of time and financial resources required for participation, fewer ties to civic organizations, lack of targeted mobilization by candidates and interest groups, and the disproportionate impact of felony disenfranchisement laws (Bruch et al., 2010). Additionally, as noted by scholars of policy feedback, the stigma associated with means-tested programs and stereotyping of beneficiaries tend to deepen disengagement (Campbell, 2007; Mettler & Stonecash, 2008; Schneider & Ingram, 1993; Skocpol, 1991). Despite these limiting factors, a substantial number of Medicaid consumers participated in the Kentucky HEALTH debate. Thus, this study takes advantage of a rare opportunity to examine how targets of public policy typically viewed as passive recipients use their own voices to construct policy narratives from the bottom-up.

Problem Definition from the Top Down Versus the Bottom Up

Reflecting the assumption that problem definition is an elite-driven process, most prior research on welfare policy has analyzed evidence from the congressional record (see Guetzkow, 2010; Hancock, 2004; Mead, 2011; Stryker & Wald, 2009) or from media coverage (see Gilens, 1999; Meanwell & Swando, 2013; Misra et al., 2003; Rose & Baumgartner, 2013). Examining the “welfare queen” policy image, Hancock (2004) argued that elected officials stereotyped welfare beneficiaries to serve their political goals, and she found no significant inclusion of beneficiaries’ voices in the congressional record or in media coverage. Only a handful of studies have involved interviews of welfare beneficiaries to analyze how beneficiaries view themselves and frame the issue of poverty (see Michener, 2018; Seccombe et al., 1998; Shildrick & MacDonald, 2013). For instance, in interviews with 47 women recipients of cash assistance in 1995, Secommbe et al. (1998) found that recipients were aware of their stigmatized status and invoked victim-blaming theories to explain other people’s reliance on government assistance, while emphasizing structural explanations to account for their own status. Shildrick and MacDonald (2013) and Willen (2012) observed that the voices of people in poverty are rarely heard, though these individuals are often talked about and theorized by others.

To begin filling this critical void, we examine two aspects of policy narratives produced by Medicaid consumers: self-description and use of story. Like other policy participants, Medicaid consumers reveal information about themselves in their public comments. They may do this to establish or enhance their standing as trusted authorities on policy, to position themselves and others like them as worthy policy beneficiaries, or to share evidence from their personal experiences that they believe to be compellingly connected to policy choices. Self-description may take on aspects of narrative (such as depicting oneself as a hero or victim), and elements of story are considered to be frequently used by policy outsiders (non-elite, infrequent participants in the policy process). Farina et al. (2012, p. 116) share their experiences leading a facilitated, deliberative online policy initiative called “Regulation Room,” directed towards policy outsiders: “When we ask for reasons and for factual support, [participants] persist in telling stories. Instead of hypothetical examples, they offer first-person narratives. Instead of logic-based reasoning from abstract principles, they support their positions with highly contextualized arguments from their own experience.” This strategy of argumentation stands in sharp contrast to the world of “professional rulemaking participants” such as career government officials and lobbyists, who tend to value “data-driven” evidence over anecdotes as evidence (Epstein et al., 2014).

Using the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) to investigate these stories of personal experience, we start by identifying gaps at the micro, or individual level of analysis. Next, we turn to our case study of Kentucky HEALTH. Through content analysis of 1100 public comments submitted in the course of three public comment periods, we show that commenters routinely relied on narratives to support their policy positions, while they rarely cited research-based evidence. Further, we find that narrative elements cohered in distinct narratives depending on commenters’ relationship to Medicaid beneficiaries. These findings underscore the importance of narratives as sources of evidence in regulatory processes and demonstrate that policy targets, much like other political actors, strategically deploy narratives to influence the policy process. Finally, based on observations from this case study, we offer five considerations for hypothesis development at the micro level of the NPF: narrator trust, forms of evidence, audience, setting, and the interaction between micro and meso levels.

Undertheorized Elements of the Narrative Policy Framework

Shanahan et al. (2017) articulate five core assumptions that form the theoretical foundation for all NPF studies. One of these core assumptions is the NPF model of the individual, the homo narrans. The homo narrans is emotional, limited cognitively, and constantly satisficing given conditions of limited attention, time, mental and material resources. Ten codified premises form the basis of the NPF’s homo narrans model, and they are overwhelmingly focused on the cognitive defaults that humans rely on as consumers of policy narratives. Only one postulate, narrative cognition, explicitly considers the productive communication methods of the individual: this postulate asserts that narrative is humans’ preferred form of internal organization of thoughts, feelings, memories, and information, and narrative is our primary communication device to the rest of the world. However, the other postulates could be reimagined in ways that inform our understanding of narrative production. For instance, the postulate focusing on heuristics notes that “individuals rely on information shortcuts to process information and to facilitate decision-making” (Shanahan et al., 2017, p. 181). Presumably, narratives are especially powerful tools of persuasion because they simplify; they distill complex realities to a limited set of narrative elements, thus drawing on and reinforcing the tendency toward heuristic processing. This same tendency should also influence micro-level narrative construction, evidenced by individuals’ reliance on their own experiences—more readily available than outside research—as the raw materials for their policy narratives. Another postulate, identity-protective cognition, asserts that individuals seek to protect their prior identities, or “who they already understand themselves to be,” which is less burdensome than re-evaluating their priors (Shanahan et al., 2017, p. 182). This tendency should not only affect how individuals respond to different narratives, but also influence their own use of narrative elements. For instance, identity protection might be apparent in individuals’ efforts to establish themselves as authoritative narrators or in the portrayal of themselves or their allies as worthy.

Thus far, micro-level NPF scholarship has not explored these possibilities, focusing instead on identifying the narrative strategies that influence individual policy preferences and conducting studies to illuminate the mechanisms by which individuals process policy narratives and express preferences. Typically, these studies have used survey experiments, exposing subjects to different narratives on the same issue, evaluating whether subjects are persuaded by these narratives, and identifying factors relevant to persuasion, such as the use of particular character types (see Jones, 2014b) or culturally or ideologically congruent themes (see Jones 2014a; Zanocco et al., 2018). Moving closer to an analysis of individuals as narrative producers, McBeth et al. (2016) studied the narrative choices of stakeholders involved in river restoration. Defined broadly as “individuals who are highly vested in a policy issue, have influence, and interest,” stakeholders include technical experts, interest group leaders, and activists (McBeth et al., 2016, p. 424); while members of the public are not explicitly included here, they are not excluded. Interestingly, the authors analyzed stakeholders at both the meso level (examining their narrative strategies for communicating with the public) and micro level, exploring the possibility that identity-protective cognition influenced stakeholders’ use of narratives. Work by Sievers and Jones (2020) similarly suggests an opening in the NPF for micro-level narrative production. The authors elaborate on three dimensions of power in the policy process and argue that narratives created by policy targets (at the micro level) can be compared to meso and macro level narratives to operationalize two of these dimensions—agenda control and domination, or “power over” (p. 103).

In short, the NPF has significant, but as yet unrealized, potential for elucidating the role of the individual as a narrative producer in the policy process. A more thoroughly elaborated model of micro-level narrative production would explain strategic decision-making in individuals’ use of narrative, including how individuals establish their authority as speakers, and the relationship of narrative production to individual and group identity, among other concepts. Further, the bottom-up methodology suggested by this approach offers two related advantages. First, it provides a counterweight to pluralistic scholarship focused on the competition among organized interests in the policy arena (Sievers & Jones, 2020, p. 97). Specifically, this approach focuses on (and can potentially yield new insights into) the role of individuals in the policy process, including how stigmatized populations speak for themselves and how they engage in collective political action. Second, this approach has the potential to address some of the criticisms of the NPF raised by interpretivists, or scholars who reject objective epistemology in favor of subjectivity as a source of understanding (Dodge, 2015). In particular, interpretivists have criticized quantitative NPF research for reducing the analysis of stories to mere statistics (and thus failing to explore narrative richness) and for neglecting the social contexts in which narratives emerge (Lejano, 2015). The elaboration of bottom-up narrative production within the NPF has the potential to encourage more immersive, qualitative research—focusing on the lived experiences of policy targets—and to correct these perceived imbalances.

Kentucky’s 2016-2019 Medicaid Debate and the Value of Studying Healthcare Policy

Kentucky HEALTH was controversial in part because it differentiated the program for different groups of consumers and proposed additional requirements for the “expansion population.” A 2014 executive order from the Democratic governor expanded eligibility in accordance with the ACA, raising the upper-income boundary to 133 percent of the FPL. Kentucky HEALTH, an initiative of a Republican governor elected in 2015 on an anti-ACA platform, bifurcated benefits packages for the “traditional” and “expansion” populations. It included community engagement requirements (volunteering or paid work) for “able-bodied” adults, a requirement to report employment status changes within 10 days, premiums, and changes or cuts to certain services such as dental and vision care for the expansion population. It also included six-month “lock-outs” for non-compliance with the new rules (Musumeci et al., 2018). The waiver was twice struck down in federal court and never enacted (Stewart & Watson, 2019). In the November 2019 gubernatorial race, Andy Beshear defeated Matt Bevin, whose administration had created Kentucky HEALTH; Beshear vowed in his victory speech on election night, “In my first week in office, I’m going to rescind this governor’s Medicaid waiver,” one of the loudest applause lines of his speech (Kentucky Educational Television, 2019).

Healthcare is an excellent domain in which to examine micro-level policy narrative construction, given the direct impact of policies in this arena on the public. In 2018, approximately 1.38 million Kentuckians were covered by Medicaid, accounting for more than 30 percent of the state’s population (Kentucky Cabinet, 2018). Moreover, the bifurcation of benefits proposed in Kentucky HEALTH and the constraints in access proposed for the expansion population engages directly with questions about who is deserving of public benefits, suggesting the centrality of characters in issue definition. Michener’s (2018) research examining the impact of federalism on consumers’ experiences with Medicaid underscores the importance of narratives in healthcare politics. She found that professional policy advocates often collected exemplary stories from Medicaid consumers that highlighted important aspects of the program that needed either preservation or transformation. One advocate described this “story-making” process as the largest initiative of their grassroots mobilization strategy. Given the diversity of Medicaid consumers—including not only those living in extreme poverty but also the working poor and those who consider themselves middle-class, qualifying for Medicaid as a result of health circumstances or care of foster children, for example—the case offers the possibility of wide variation in the use of story.

The case of Kentucky HEALTH also represents an opportunity to apply the NPF to a new communication forum: public comments in the rule-making process. Prior NPF research has focused on “public consumption documents”—such as press releases, newsletters, and social media posts—with presumably wide-ranging purposes, from education to mobilization, and diverse audiences, from citizens to policymakers (Shanahan et al., 2018). Narrative strategies in these forums may thus be intermingled with other elements of communication. Public comments, in contrast, have one clear purpose and audience: persuading government agency officials (in this case, the CMS, and, to some extent, the Bevin Administration) to adopt (or not adopt) proposed rules. This specificity, in turn, may be associated with greater prominence and clarity of narrative communication: more signal, less noise.

Scholars have just begun to examine the rollout of Medicaid expansion under the ACA, and few studies have looked at the handful of states that submitted Section 1115 waivers (see Baker & Hunt, 2016; Stewart & Watson, 2019). Two studies have assessed the framing of policy debates in states with Medicaid waivers (see Grogan et al., 2018; Jarlenski et al., 2017). Analyzing nearly 300 public comments on Section 1115 waiver applications in five states, Jarlenski et al. (2017) found a high percentage of comments from Medicaid-eligible citizens, most of which expressed disapproval of controversial waiver provisions. Given that previous research on the rule-making process suggests that the public plays a very limited role (Golden, 1998; Yackee & Yackee, 2006), this finding is striking. Further, the authors found that citizen commenters were more likely to use anecdotes than research-driven arguments. To extend this line of research and to shed light on citizens’ role in Medicaid policymaking, we focus on the following research questions:

RQ1: How prevalent are narratives in the public comments in relation to research-based content?

RQ2: How does use of narrative elements (character and setting) vary as a function of the commenter’s self-description?

RQ3: What types of stories do Medicaid consumers tell, and how do those stories differ from those told by other types of commenters?

Research Methods and Data

We collected all public comments from three separate comment periods—spanning from September 2016 to August 2018—from the CMS website. After eliminating duplicates and comments with no substantive content, we paired the dataset down to 11,640 comments. The large volume of comments is attributable in part to grassroots mobilization efforts by various interest groups, including a joint effort by Kentucky Voices for Health and the Kentucky Equal Justice Center. Using Survey Monkey, these two organizations created a three-minute survey that prompted citizens to describe their experiences with Medicaid and how the proposed changes would affect them (Stewart & Watson, 2019). The groups’ explicit intention with this approach was to elicit the personal stories of Medicaid consumers rather than to generate impersonal, “form letter” style comments (Stewart & Watson, 2019). The groups then submitted the survey responses as public comments to CMS. We determined that approximately 70 percent of the total comments were responses to a prompt, most from this survey.

From this dataset, we randomly sampled 1100 comments for manual content analysis, with major attributes of the comments summarized in Table 1. For each comment, we coded for position on the waiver, relationship to Medicaid consumers, and the use of narrative elements, focusing on characters, setting, and solutions, among other attributes.[2] We identified three policy positions: 1) pro-Medicaid, expressing support for Medicaid with no mention of the waiver; 2) oppose waiver, expressing objections to aspects of the waiver or to the waiver as a whole; and 3) support waiver, expressing support for specific aspects of the waiver or for the waiver as a whole. We also noted comments which expressed no policy position.

For relationship to Medicaid consumers, we identified seven categories: 1) current self; 2) past self or family; 3) current family member (excluding self); 4) other relationship, in which the commenter identified a friend or acquaintance as a Medicaid consumer; 5) advocate, in which the commenter identified as an advocate or representative of an interest group; 6) service provider, in which the commenter described a professional role working directly with Medicaid consumers, such as a health care provider or social worker; and 7) unidentified, in which the commenter did not identify his/her relationship to Medicaid consumers. While these categories were not mutually exclusive, just 1.4 percent of comments identified more than one relationship to Medicaid consumers (e.g., service provider and family member).

Table 1. Summary of Data by Commenter Type

| # of Comments

(% of Total) |

Mean Word Count | # of Comments Responding to a Prompt | Policy Preference (Number and % Total in Category) | ||||

| No Position

|

Oppose Waiver

|

Pro-Medicaid

|

Support Waiver

|

||||

| Current Self | 272

(24.7%) |

64.7 | 196

(72.1%) |

15

(5.5%) |

178

(65.4%) |

77

(28.3%) |

2

(0.7%) |

| Past Self or Family | 37

(3.4%) |

72.9 | 22

(59.5%) |

1

(2.7%) |

12

(32.4%) |

22

(59.5%) |

2

(5.4%) |

| Current Family Member | 126

(11.5%) |

81.4 | 76

(60.3%) |

4

(3.2%) |

81

(64.2%) |

39

(31.0%) |

2

(1.6%) |

| Other Relationship | 49

(4.5%) |

93.2 | 34

(69.4%) |

1

(2.0%) |

34

(69.4%) |

10

(20.4%) |

4

(8.2%) |

| Advocate[3] | 4

(0.4%) |

170.3 | — | — | 4

(100%) |

— | — |

| Service Provider | 117

(10.6%) |

107.9 | 68

(58.1%) |

1

(0.9%) |

92

(78.6%) |

19

(16.2%) |

5

(4.3%) |

| Unidentified | 513

(46.6%) |

79.2 | 333

(64.9%) |

34

(6.6%) |

342

(66.7%) |

60

(11.7%) |

77

(15.0%) |

We also constructed dictionaries of keywords and phrases relevant to selected aspects of narrative and non-narrative content, including references to a geographic location (i.e., setting) and to research or empirical evidence.[4] We used a computer content analysis program, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), to identify comments in which these topics appeared and to calculate other features of interest, including word count and references to quantifying language (see Berry et al., 1997; Pennebaker, 1997).

Our qualitative analysis focused on three types of commenters—current Medicaid consumers, past consumers, and service providers—and used an inductive social constructivist approach to identify similarities in perceptions and consequences of reality within and across groups (i.e., commenter types). In our sample of 1100 comments, 92 commenters supported Kentucky HEALTH; of those, only 15 identified their relationship to a Medicaid consumer (2 current consumers, 2 past consumers, 5 service providers, 6 family members and other relationships). The small number of comments in our sample supporting the waiver reflects the overall narrative landscape in which the public comments were heavily weighted toward opponents of changes proposed in Kentucky HEALTH.[5] While our qualitative analysis focuses on commenters who supported either expanded Medicaid or opposed Kentucky HEALTH, we briefly summarize similarities among the five comments by service providers who supported the Kentucky HEALTH waiver. To assess for thematic patterns, all comments were read through once without coding, followed by an open coding step. Then patterns of themes were proposed, tentative descriptions developed, and comments were coded for presence and absence of the theme, with descriptions modified as appropriate until the analysis reached saturation and the descriptions were finalized (see Table 2). Themes are intended to have descriptive integrity but are not mutually exclusive.

Results

The Prominence of Narratives

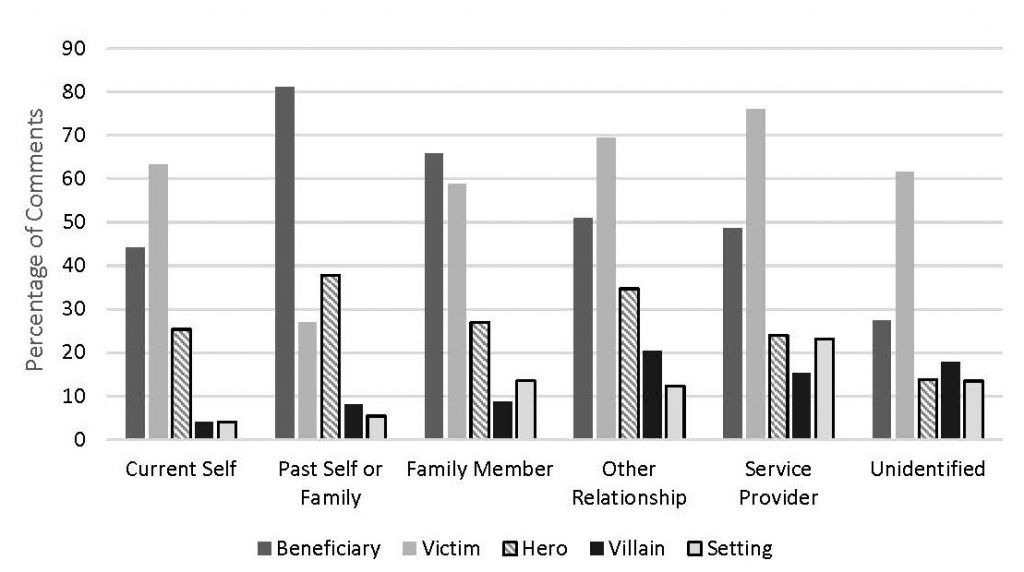

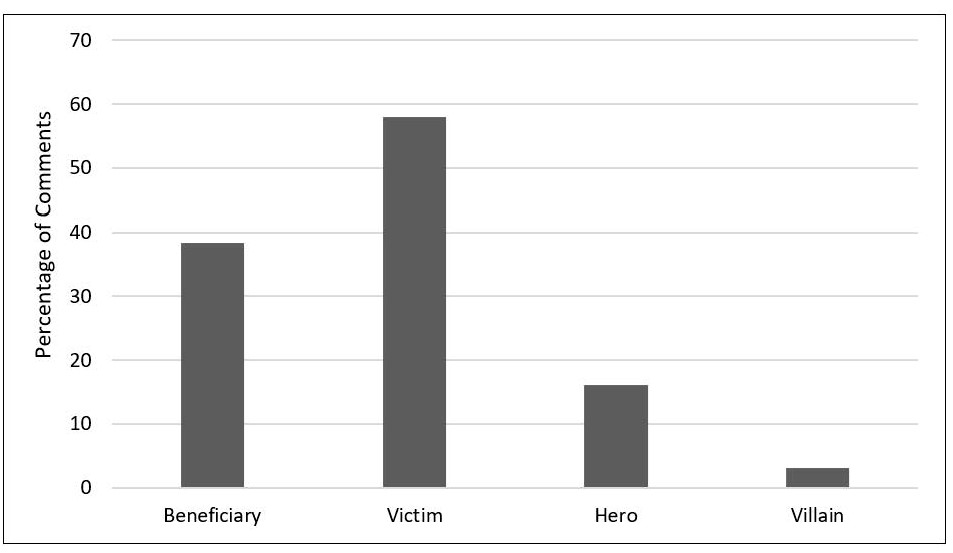

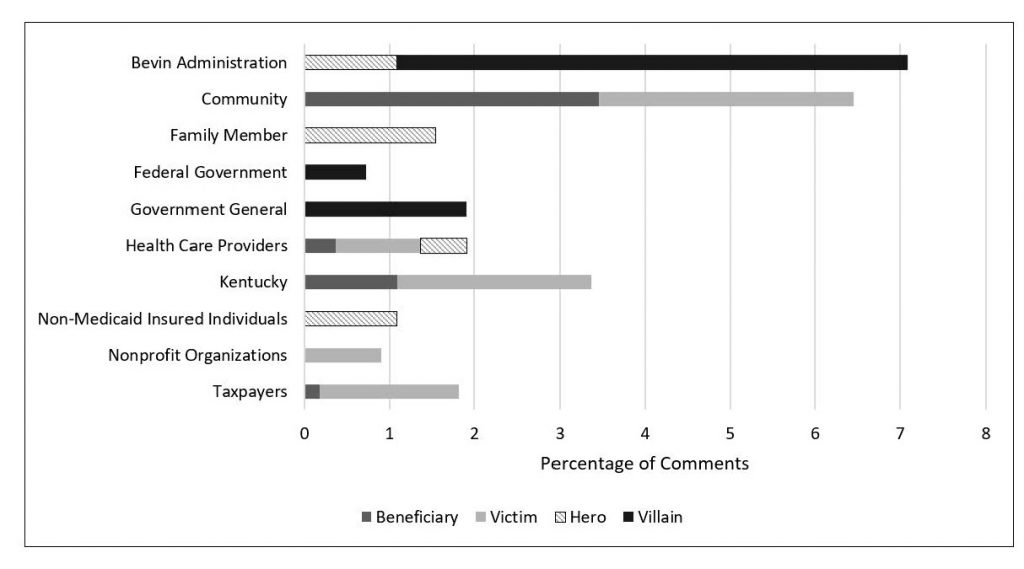

To determine the prevalence of narratives in the public comments, we calculated the percentage of comments that referred to at least one character and one solution, i.e., the minimum threshold for a narrative, as identified by Shanahan et al. (2018). 993 comments (or 90.3 percent of total comments) cleared this threshold. In fact, every comment mentioned either Medicaid or the waiver, in general or specific terms, and the average number of narrative elements per comment was 2.9. The most common character type was victim, appearing in 62.4 percent of comments, followed by beneficiary (in 40.3 percent of comments), hero (in 20.4 percent of comments), and villain (in 12.7 percent of comments). Setting appeared in 11.8 percent of comments.[6] Figure 1 illustrates the percentages of comments containing these narrative elements, separated by relationship to Medicaid consumers. As indicated by varying emphases across narrative elements, different types of commenters told different stories, with current Medicaid consumers placing more emphasis on victims than on beneficiaries, and past Medicaid consumers doing the opposite.[7] Current consumers and family members were also less likely to use villains than the other commenter types.[8] Finally, setting also appeared more prominently in the narratives of service providers.[9]

Figure 1. Percentages of Comments Containing Characters and Setting

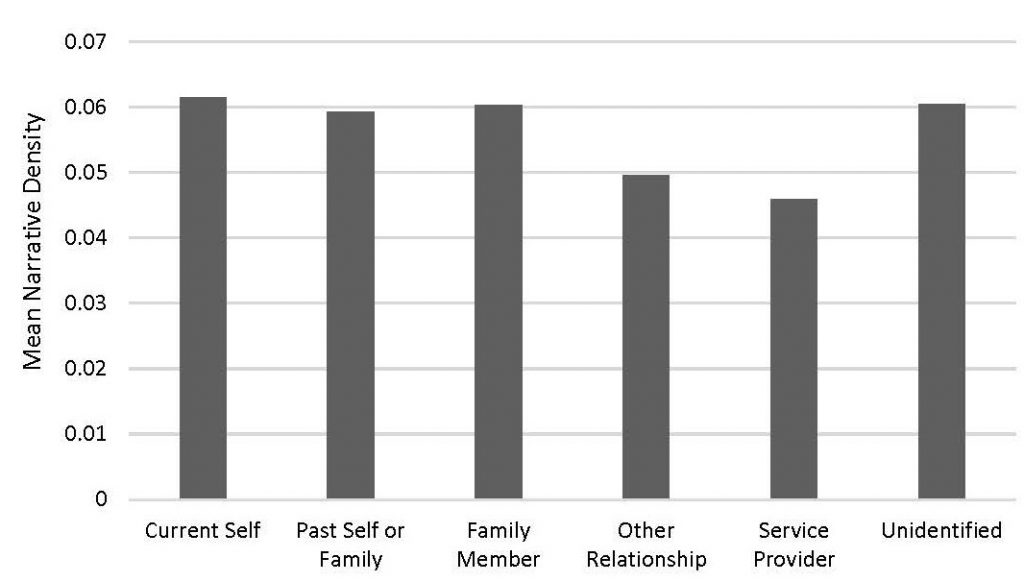

In addition to assessing variations in emphasis, we examined how densely packed commenters’ narratives were. Specifically, we calculated the sum of narrative elements per comment—i.e., total characters plus total solutions and setting—and then divided total narrative elements by the comment’s word count. This ratio, which we call narrative density, captures the extent to which a comment is devoted to narrative versus other elements and is distinct from other measures of narrative density, such as chronology and information units (Fivush, 1991). As indicated in Figure 2, current Medicaid consumers had the highest narrative density, while service providers had the lowest narrative density.[10]

Figure 2. Mean Narrative Density (Total Narrative Elements/Word Count)

Stated differently, while current Medicaid consumers typically wrote short comments, their statements packed a strong narrative punch. In contrast, service providers’ comments contained narrative elements as well as other non-narrative content, including details about their professional backgrounds and about the policy impacts—in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and feasibility—of Medicaid and of Kentucky HEALTH.

Research-Based Content

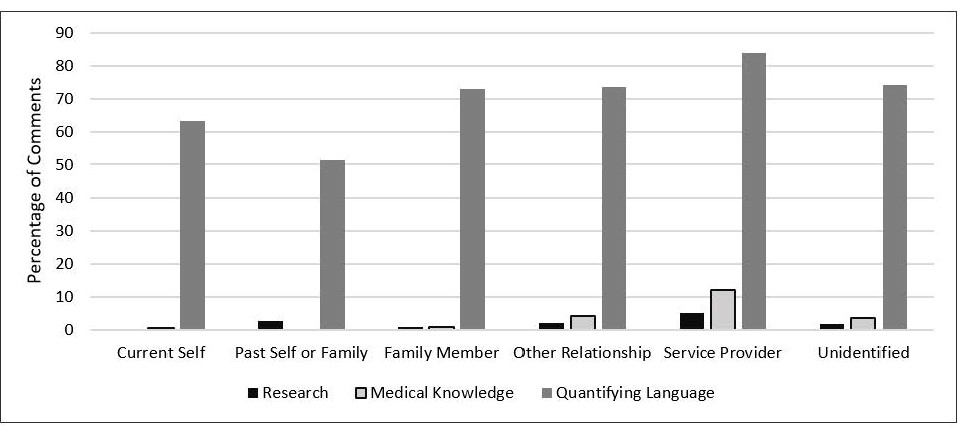

To assess the use of research-based and data-driven arguments in the public comments, we examined three attributes: 1) references to research, based on our dictionary and calculated automatically by LIWC; 2) references to medical knowledge, such as the relationship between dental and cardiovascular health (coded manually); and 3) quantifying language (e.g., “average,” “few,” “percent”) based on an internal LIWC dictionary and calculated automatically.

Figure 3. Percentages of Comments Containing Research-Based Arguments

As indicated in Figure 3, references to research and medical knowledge were rare; service providers had the highest percentages of both, at 5.1 and 12 percent, respectively.[11] Quantifying language was more common—reflecting the fact that this dictionary, with terms such as “many” and “each,” captures much more than references to data—though it was also highest among service providers.[12]

Qualitative Analysis of Storylines

As the preceding quantitative analysis demonstrates, frequencies of narrative and non-narrative elements varied across different types of commenters. Next, we examine how these narrative elements cohered in distinct storylines. We focus our qualitative analysis on pro-Medicaid expansion/anti-waiver comments by current Medicaid consumers, past Medicaid consumers, and service providers. Based on differences in use of characters, setting, and research-based content uncovered in the quantitative analysis, these were the three types of commenters that we anticipated might tell different stories.[13] This analysis reveals that most narratives that support the status quo (Medicaid expansion) make use of one of two overarching perspectives, summarized as “Medicaid is part of a system working as it should” and “Medicaid is a remedy to an otherwise broken system.” These are further broken down into nine themes, summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Perspectives and Themes in Comments Supporting Expanded Medicaid and/or Opposing Kentucky HEALTH

| Perspective | Theme | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Medicaid is part of a system working as it should. | I get the care I need. | Commenter asserts that Medicaid enables access to healthcare. |

| I fell on hard times and the safety net caught me. | Commenter describes a temporary setback or life challenge made less acute by Medicaid. | |

| Medicaid saved my life. | Commenter claims that Medicaid enabled healthcare access that likely prevented someone’s death. | |

| Medicaid is a ladder of opportunity. | Commenter describes journey of upward mobility made possible by Medicaid. | |

| Medicaid cascade | Commenter claims Medicaid contributes to downstream, non-medical individual, group and/or societal outcomes. | |

| These changes won’t work in real life. | Commenter describes proposed waiver changes as difficult or impossible to implement in consumers’ lives and/or in administrative systems. | |

| Medicaid is a remedy to an otherwise broken system. | Despite my hard work… | Commenter describes the disparity between the hard work of low-income people and their rewards, of which Medicaid is one of the few benefits. |

| It’s Medicaid or nothing at all. | Commenter describes Medicaid as the only available route to healthcare access. | |

| Healthcare is an unrealized human right. | Commenter evokes moral or social obligation to provide universal access to healthcare. |

Each commenter type had strong representation of the most forthright theme, “I get the care I need.” Current Medicaid consumers were also noteworthy for their more frequent use of two themes related to feasibility (“These changes won’t work in real life” and “It’s Medicaid or nothing at all”), which focus on the nuts and bolts of low-income consumers’ lived experiences of Medicaid access. Past consumers were more likely to emphasize Medicaid as a buffer to life’s challenges and as a ladder of opportunity, helping to lift people out of poverty. Service providers, like the current Medicaid consumers, defended the status quo by stressing the difficulties in implementing proposed changes, such as work/volunteer requirements, co-pays, and eligibility lock-outs. Service providers, much more than any other commenter type, used the theme of the “Medicaid cascade,” focusing on the larger societal implications of Medicaid access and the downstream effects of Medicaid policy changes on individual and community well-being, family functioning, and local economies.

Almost all of the current Medicaid consumers in our sample depicted Medicaid as a successful tool in a functional system or as a rare bright light in an otherwise dysfunctional system. Comments holding the perspective of “Medicaid is part of a system working as it should” can be further divided into four themes. In the first theme (“I get the care I need”), Medicaid consumers focused on program effectiveness as assessed by Medicaid’s straightforward policy goal of increasing access to medical services. This theme is exemplified in the following comment: “I had to have gallbladder surgery two years ago. I would not have been able to have it without Medicaid. My daughter has to have therapy and the insurance covers everything. I am a single working mom and money is stretched thin at our house.”[14] The implicit argument in comments of this type is that Medicaid is functioning as designed by relieving the commenter’s personal health and economic burdens.

In the second theme, “I fell on hard times, and the safety net caught me,” current and past consumers described temporary setbacks and vulnerabilities (e.g., injury, illness, divorce, job loss) that were made less acute by Medicaid eligibility. These comments often contained significant personal details, such as medical diagnoses, local place names, family relationships, personal incomes, work histories, and more, as in the following:

My husband’s company closed their stores and he lost his job AND his insurance. Because of his age, it was difficult for him to find employment. The ACA allowed him to obtain insurance and get the first check-up he had been able to obtain in years. It was then that we discovered his cancer. We were lucky that we were able to catch it early. If we hadn’t had the Medicaid, we might not have caught it until it was much farther advanced. The Medicaid expansion saved his life. (excerpt)

Implicit in these comments is an assumption that Medicaid provides relief from the sometimes cruel and unpredictable trials of life; the system is virtuous because it contains an accessible Medicaid program, and Medicaid protects people from the challenges attendant with human frailty.

In the third theme, “Medicaid saved my life,” commenters made the claim that the alternative to Medicaid access is death, as in the following:

I can’t afford insurance and my employer doesn’t offer it so my kids and I would not be able to afford to get sick or regular check ups without it. If I didn’t have medicad I never would have gone for a regular check up where the doctor was concerned over the appearance of a cyst that I didn’t notice. He never would have ordered test to make sure I was fine. The cancer would have ravaged my body and I would have died at 32 leaving my two children without a mother.

This theme positively portrayed access to life-saving medical care and often included dramatic details of grim alternate realities without Medicaid: orphaned children, death, and suffering were all avoided because of the presence of Medicaid. Implicit in these arguments is the assumption that all human life has inherent value and that Medicaid should be preserved because of its role as a protector of human life.

In the fourth theme, “Medicaid is a ladder of opportunity,” commenters explained how Medicaid enabled them to progress from a less desirable past status to achieve upward mobility, as in the following comment from a current consumer: “Medicaid has allowed me to leave a bad job that I stayed in for years because of the employer provided insurance. It has now allowed me to go back to school full-time to improve my job skills without worrying about my healthcare.” Drawing on the traditional American value of self-reliance, these comments suggest that Medicaid rescues people from poverty and enables the fulfillment of human potential by helping people help themselves.

This theme was even more pronounced among past consumers, who were also more likely, according to our quantitative analysis, to use beneficiaries as characters. We see both of these characteristics in this comment:

The peace of mind that came with my Passport Health insurance through KY Medicaid helped me through three years of schooling, to where I am now. I have a secure job that provides health benefits. And I will gladly and openly continue to pay taxes so my Kentucky neighbors who are less fortunate can feel the peace of mind I did. (excerpt)

Such comments present before-and-after redemption stories of beneficiaries- or victims-turned-heroes, which foreground the use of public assistance as a tool of uplift rather than dependence. Commenters implicitly evoked cost-benefit arguments as they revealed that the temporary use of public funds in the past has yielded personal and societal dividends; they are self-sustaining economically contributing taxpayers.

In the fifth theme, “These changes won’t work in real life,” current consumers emphasized the gap between proposed expectations (work, volunteering, reporting income changes) and details of their lives that would likely work against successful compliance with these rules:

If premiums are raised and the 80 hour work mandate is enforced, as a single parent who is solely responsible for 2 elementary aged children, I will not be able to keep my coverage. I cannot afford, even working 2 jobs, the cost of childcare to keep up with the mandated hours. Right now I can only work while my children are at school because I cannot afford daycare or a babysitter.

Consumers discussed barriers to compliance such as frequent changes in income that would make it difficult to comply with proposed rules for reporting within 10 days, lack of transportation, lack of funds for co-pays, few jobs and volunteer opportunities available, and trouble understanding and keeping up with all the rules. In many of these comments, consumers argued that if these proposals were adopted, they would surely lose their coverage. Similarly, service providers shared stories of how the rules would not work well for consumers or for themselves:

As pastor of a church, we would anticipate a large number of people needing to get those hours in by volunteering for us BUT that is not a very helpful way for us to manage. We don’t have staff or time to manage untrained and sometimes unknown volunteers. It sounds good on paper, but our experience with other enforced volunteer programs (like court ordered community service) proves otherwise.

Emphasizing a disconnect between what works “on paper” and in real lives, these comments implicitly endorsed the current program as the most feasible and frictionless way to meet Medicaid’s core goal of expanding access to healthcare.

In contrast to these themes focusing on the positive impacts of the status quo version of Kentucky’s Medicaid program, comments aligned with the overarching perspective that “Medicaid is a remedy to an otherwise broken system” highlighted the struggle that Medicaid consumers face in a system that offers few benefits. In the “Despite my hard work…” theme, commenters emphasized a disparity between what they put into the system (years of hard work) and what they can get out of it (private health insurance is still unaffordable). Medicaid is the exception to a system that offers few rewards, even to people who work multiple jobs, such as this commenter: “I work 2 jobs, one being a full time state merit employee and still qualify for Medicaid. I could not afford to pay insurance for my daughters and my self. Not everyone that a medical card is unemployed or lazy!! By the way…I am not on ant other type of government assistance.”

Comments that used the theme “It’s Medicaid or nothing at all” depicted a barren landscape of health insurance options, with Medicaid portrayed as the only route available. This resembles the “Medicaid saved my life” theme, but with less emphasis on the positive and more on the absolute dearth of options. Implicit in this argument is the assumption that Medicaid is valuable because it is the singular provider of a unique service; without it, consumers have no feasible choices:

Expanded Medicaid coverage has, for me, been the difference between incurring massive crippling debt and having to beg for help from pharmaceutical companies and my physicians. It has made and kept me healthier. It has meant that the last two surgeries I’\’ve needed due to degenerative arthritis complications didn’t leave me broke – or broken, because I wouldn’t have afforded them otherwise. I am a long-term (30+ years) Type 1 Diabetic. Finally having prescription coverage after decades without, I no longer have to portion out how often I use glucose meter strips or wonder if taking the insulin necessary to treat an unexpected high will leave me without enough to get through the month. I have Psoriatic Arthirtis. The x-rays and other diagnostics it took to get me diagnosed; the biologic medication that keeps me _functional_; the surgeries I’ve needed and the treatments I will continue to need – ALL of these were made possible by Medicaid. I’d be a shadow of myself (if I wasn’t dead) without this insurance.

The theme “Healthcare is an unrealized human right” is ubiquitous in health insurance policy debates but appeared rarely in this sample of current Medicaid consumers. Comments using this theme focused on the moral flaws in limiting access to care, as in the following:

Now on medicaid, I was able to go to the UofL dental school and found I had a severe tooth infection. They pulled the tooth and treated the infection. If I had waited longer, I could have died leaving my child an orphan and my aging sick mother to care for her. It tears me up to think that something as simple as this out patient procedure that saved my life could be withheld from someone else. (excerpt)

Another commenter focused on the relationship between poverty and healthcare access, evoking questions of society’s moral obligations to the poor:

If the new law happens a lot of poor people will get sick and die. This is a crazy law I think everyone should get free health care. I know how it was before I couldn’t even go to the dr. I was very sick and high blood pressure and couldn’t even get my meds. So please listen to the poor people cause we are the ones affected by what you do. (excerpt)

As highlighted in the quantitative analysis, service providers were more likely than other types of commenters to use research-based content and setting in their comments. Our qualitative analysis demonstrates that they also made use of a theme we call the “Medicaid cascade” in which they emphasized downstream effects of access to healthcare, for individuals and communities:

Poor dental care leads to many other physical ailments and exacerbates cardiac issues such as valve issues. Low-cost routine dental care, therefore, also helped avoid high-cost cardiac issues later. Lastly, the impact on lost productivity, school attendance, and job retention cannot be understated. The majority of our Medicaid recipients also work, some more than one job, but by in large are in service-industry jobs that pay very little with no benefits. Those jobs tend to be very susceptible to absenteeism, and when recipients miss days of work due to illness or to go to specialty care, they often lose their jobs. This is a strain on the members as well as employers. (excerpt)

In comments using this theme, Medicaid is portrayed as an enabling condition of well-being; it creates the opportunity for a variety of personal and social goods, such as better health, improved family functioning, stress reduction, decreased healthcare costs, improved productivity, higher school attendance, and employee retention. An investment in a public health insurance program, the logic follows, is also an investment in sectors such as education and the economy.

On the other hand, service providers also discussed constraining factors, and more commonly than other commenters, used setting to evoke limiting structural conditions. Service providers occasionally used setting simply to identify their connection to an area of the state or the context in which they provide services to Medicaid consumers (e.g., “I am a resident physician at a very busy downtown urban hospital”). The following comment uses setting as shorthand for limited opportunity:

As a physician here in Eastern Ky. we considered Medicaid and Medicare the premium third party payors. When people are caught in an endless loop of poverty with all its attendant problems, Medicaid is a true life saver. Until you have worked in this environment, you can’t know how access to health care keeps a community going, in the face of every other horror it has to face. I had a patient who walked 3-4 miles to our clinic for his Medicaid financed health care. Because he was intellectually challenged, he had not gone far in school. There were no jobs he could walk to. He couldn’t afford a car, nor drive one if he had one because he didn’t have a license. He didn’t have a way to drive to town to take the driving test. What would Bevin’s ideas done to this man, who through no fault of his own was stuck forever in his life, but without complaining, somehow made it work?

In these comments, service providers depicted unforgiving settings as a foil to their victim characters, whose efforts at self-improvement and program compliance are stymied by the infrastructure limitations of their communities. Challenging settings evoke sympathy for the characters caught within them.

Because our sample contained a limited number of pro-waiver comments, we do not provide a comprehensive comparison of their themes by commenter type. Overall, pro-waiver arguments touched on familiar themes such as concerns about government spending, promoting personal responsibility, and the benefits of work for individuals and societies. Of note is the variation in the use of the specific term “able-bodied” by pro-waiver commenters and those opposed to the waiver. The phrase “able-bodied,” which has no formal medical definition, was particularly charged in public debates over Kentucky HEALTH. Advocates opposed to the waiver questioned its validity as a concept let alone as a basis for restricting access to health benefits (see Agarwal, 2019), and those supporting the waiver wondered why this categorization was not readily understood as a common sense method of sorting the truly deserving from those inappropriately receiving more than their fair share (see Schickel, 2018). The phrase “able-bodied” is used by 14 individuals in our sample of 1100 comments; and while pro-waiver comments are less than 10 percent of our sample, they make up almost half (6 of 14) of commenters using the term. This suggests a focus on personal character traits and deservingness among pro-waiver comments that is also reflected in the five comments by pro-waiver service providers. Pro-waiver service providers claimed to have witnessed ungrateful, selfish, or deceitful behavior by Medicaid consumers, such as in this (excerpted) comment: “Hopefully, these changes would cut down on people running to ER to get out of working. I’ve seen this with my own eyes, as I work with women who live in a transitional living facility. They fake sick, run to ER, and get fired from their job.” Implicit in these comments is the assumption that the undesirable activity witnessed directly by these commenters is widespread, and that the system would be fairer if its rules were better designed to prevent unethical behavior.

Discussion

Both the quantitative and qualitative analyses of public comments in response to Kentucky HEALTH demonstrate that bottom-up narrative construction is quite common. More than 90 percent of comments met the minimum threshold for a narrative, and most exceeded it, mentioning multiple characters or solutions, or evoking a particular setting. Further, we argue that these narratives were strategic, demonstrating “goal-seeking behavior via patterns of narrative element usage” (Jones, 2018, p. 729). While narrative strategies have previously been identified only at the meso level, the evidence of strategy at the micro level is strong: almost all commenters (95 percent) identified their policy positions and selected narrative elements to support those positions. Additionally, narrative elements and storylines differed by commenter type, suggesting meaningful differences in narrative strategy depending on commenters’ relationship to Medicaid consumers.[15] As highlighted in the qualitative analysis, these were gripping narratives, revealing deeply personal information and emphasizing the life-and-death consequences of policy choices.[16]

Many of these narratives served to flesh out characters or concepts that remain abstract or reflect composite types at the meso level. For example, meso-level debates over Kentucky HEALTH often involved ethical arguments over new requirements for able-bodied adults. In the micro-level narratives, individuals explain the complexity of operationalizing a clear definition of “able-bodied” and detail their daily struggles to navigate complex systems. They explain why seemingly common sense rules could pose stiff challenges in the context of real people’s lives. Individual narratives, to a degree that is strikingly different from typical meso-level stories, feature deeply personal and private health and emotional information, offered as first-hand testimonial and as evidence for policy positions.

We contend that these narratives were not simply reflections of narratives created at the meso level, as might be assumed when one conceptualizes individuals as primarily narrative consumers. Rather, narratives at all three levels of analysis contain a mix of original content (production) and narratives told and retold by other actors (reproduction). At the meso level, for instance, coordination among actors within political coalitions likely involves cue-taking on narrative form and content. At the micro level, individuals likely absorb and repeat some meso level narratives, but also contribute their own stories (which may then be transmitted up to the meso level). To distinguish between production and reproduction at the micro level, one might examine the extent to which meso-level actors solicit or otherwise shape the narratives of individuals. In the case of Kentucky HEALTH, a substantial number of comments were, in fact, form letters, most notably from groups representing the cystic fibrosis and blood cancer policy communities, though we filtered those comments out of the analysis. While many of the remaining narratives were the result of individuals’ responses to questions in a survey, the responses themselves were original, and the survey did not inflate the prominence of narrative communication in the comments. Specifically, comments submitted independently of grassroots mobilization efforts were also densely packed with narrative elements. A two-sample t-test indicated that comments submitted independently contained significantly more narrative elements on average (3.4) than comments responding to a prompt (2.6) (t = 9.2, p < 0.01).

Our data do not speak directly to the power of these narratives, though the public record suggests that narratives in the public comments influenced both policy and politics. Namely, the federal district court judge who twice struck down the Kentucky HEALTH waiver specifically mentioned the narratives of Medicaid consumers, family members and friends of Medicaid consumers, and social service agency workers in the court’s opinion to support the finding that the proposed changes would cause people inadvertently to lose coverage (Stewart & Watson 2019, pp. 215–217). This is not to say that research-based testimony was not influential; in fact, Judge Boasberg cited 16 comments from advocacy groups whose testimony included evidence from past Medicaid demonstrations. As noted by Stewart and Watson (2019, p. 221), however, the personal stories of Medicaid consumers likely served to “humanize the data,” showing “how research translates into practice.” In addition, the 2019 governor’s election resulted in a win for Democratic candidate Andy Beshear, who campaigned in support of expanded Medicaid; his first televised ad in April of 2019 centered on a child with Type I Diabetes whom Beshear vowed to protect from policies that might deny him health care coverage.

While generally underscoring the importance of micro-level narrative production, these findings also suggest that public comment during rule-making is a rich and meaningful source of narrative. The specificity of purpose and audience may be especially conducive to consistent, clear narrative communication. Suggesting a heightened sense of audience, commenters in our study occasionally broke down the “fourth wall,” addressing government officials directly, as in the following (excerpted) comment: “Shame on you Gov. Bevin. When you ran for governor I was an avid supporter. . . . I believed you were an advocate of childrens health because of your beautiful family. Boy, was I ever fooled.” Future research at the meso level could investigate whether breaking down the fourth wall occurs in other forums, while micro-level research could examine how this practice influences narrative persuasion. In part, our finding of substantial narrative content in the public comments may reflect the fact that the health policy domain is particularly conducive to first-person anecdotes. Other arenas that might also prominently feature experience-as-evidence include nutrition assistance (and other means-tested government assistance programs), civil rights, and policies affecting children. Future NPF research should thus examine rule-making in other domains to determine the extent to which these findings are generalizable.

Developing Micro-Level Theory

We have identified a considerable gap in NPF micro-level theory and seek in this study to advance the elaboration of a model of the individual-as-policy-narrative-producer. We emphasize five areas ripe for further investigation by researchers seeking to develop new micro-level theory. We offer guidance on hypothesis-generation regarding narrator identity and narrator trust, forms of evidence, audience, setting, and the interaction of meso and micro levels.

Hypotheses at the micro level should describe and illuminate the relationship between the policy commenter (narrator) and the target population(s) of the policy. Unlike advocacy groups, which typically have status and reputation as members of a policy community, individuals may not have immediate access to a well-known identity that establishes the validity of their policy opinions and may seek to credential themselves in other ways. They may enhance their credibility and gain the audience’s trust by describing themselves in terms of their connection to real people and events affected by the policy in question. This form of self-description may be strategic insofar as it seeks to persuade the audience that the narrator is a direct observer and reliable witness, or it could be reflective of identity-protective cognition, or both. Future research should investigate which aspects of self-description generate the most trust, whether policy networks influence the bounds of acceptable narrator identities, and whether there are effects of congruence/incongruence with narrator self-description. Would a narrator who claims a particular identity, such as a crusading mother, be rewarded for playing to type or punished for violating pre-conceived notions of appropriate behavior for the role?

Future research should also explore whether individuals who employ research-based content—which carries its own authority but may be burdensome to obtain and use—instead of or in addition to anecdote vary in their level and type of self-description from those narrators who rely exclusively on anecdote. These decisions—whether to employ facts or stories (or both), whether to provide few or many personal details and of what kind—likely reflect individual policy narrators’ assumptions about their audience’s preferences and what will move the audience to adopt the policy option preferred by the narrator. We found it noteworthy that very few commenters in our sample made use of a human rights argument for healthcare access, and that many commenters told of Medicaid saving their lives and lifting them out of poverty. This may reflect an assumption that human rights language would be off-putting to the government agents involved here, and that they would more likely be swayed by tales of Medicaid uplift. Questions of audience become even more interesting when the venue is a public comment process. Public consumption documents—at an individual level, common examples would be social media posts or letters to the editor—have a diffuse audience, but public comments are intended to persuade a government official of some sort. With public comments, understanding the narrator’s assumptions about the audience’s values simultaneously illuminates assumptions about government values and the narrator’s relation to them. Questions of audience values may be particularly salient in debates over redistributive programs like Medicaid, in which policy narrators must make critical assumptions about their audience’s perceptions of the deservingness of policy beneficiaries. Hypotheses at the micro level should describe policy narrators’ assumptions about audience that are inherent in their strategic decisions regarding forms of evidence, self-description, issue type, and audience type.

Both our quantitative and qualitative analyses demonstrated differences in how commenters used the narrative element of setting. Within NPF studies, setting may be broadly defined as a policy context (legal, discursive, social and economic parameters), as a conceptual place (“the American West”) or as a specific geographic place or location. Even with such an expansive definition, investigation of setting is relatively rare in the NPF literature (for an exception, see Merry, 2020). Hypotheses at the micro level should elucidate two aims of the strategic use of setting: enhancing narrator trust and evoking structural constraints on character autonomy. Commenters of all types in our study used setting as a way to enhance narrator trust, by identifying their connection to a locale affected by the policy in question, whether a city, county, region, or the commonwealth. Their connected geographies enhance their legitimacy as narrators in two ways: first, they evoke the democratic concept of the agora, in which residence confers authority to speak, and second, they establish their direct knowledge of the characters and plots they describe. They live and work here, implying that the stories they tell us are those they have experienced or seen first-hand, and they have a personal stake in the outcome as residents of a shared polis. The second direction for future research on setting examines how it can function as shorthand for larger societal forces and influence how we view the characters within a setting. The service providers in our sample used setting more often than other commenter types and were more likely to describe challenging settings that limit the opportunity for upward mobility. The inability of Medicaid consumers to achieve economic self-sufficiency was depicted as a function of a setting’s inadequate infrastructure (transportation, internet, medical facilities, available jobs) rather than a personal failing. Descriptions of structurally limiting settings can be a strategy to enhance the worthiness of stigmatized beneficiaries.

Future research may also clarify (or complicate) conceptions of the relationship between micro- and meso-level narratives. Previous NPF schematics of this relationship have relied on the prevailing assumption of individuals as policy consumers. These schemata (see Peterson & Jones, 2016; Shanahan et al., 2017) describe a process in which advocacy coalitions at the meso level generate policy narratives that compete to influence individuals. Aggregated individual opinion becomes public opinion, which influences the policy agenda and may eventually become policy outputs. In these schemata, individuals do not influence advocacy coalitions; instead, they consume and respond to advocates’ narratives. Hypotheses at the micro level should examine how individual narratives influence the development of meso-level narratives, the extent to which individual and meso-level narratives are congruent, and how advocacy groups at the meso level strategically engage individuals to generate original narratives, or to amplify themes deemed advantageous by advocacy coalitions. While these hypotheses may blur the boundaries between meso and micro levels, they offer the potential to uncover a more nuanced understanding of narrative contestation and change over time and invite diverse methodologies, including both positivist and interpretivist approaches.

In July 2019, for the fourth time, Judge Boasberg vacated federal approval of a state’s Medicaid Section 1115 waiver (Rosenbaum 2019). This time it was New Hampshire’s “Granite Advantage”; he had previously ruled against Arkansas’s Medicaid program and twice against Kentucky HEALTH. “We have all seen this movie before,” he wrote in his decision, rather wearily evoking the pattern of pro-waiver arguments marshaled repeatedly to defend attempts to modify Medicaid eligibility and consumer requirements. His cinematic comment reflects the drama of the policy process at the meso level, with policy actors vying for venues and exploiting every procedural plot twist possible to keep their policies in play. The world of individual-level policy narratives is also cinematically rich in meaning, laden with value judgements and inhabited by strategic actors. We look forward to future research that will reinvigorate the NPF model of the homo narrans as an active participant in the production of policy narratives.

References

Agarwal, Sumit. 2019. “Medicaid Work Requirements in Kentucky: Identifying the Able-bodied and Holding them Accountable.” JAMA Network Open 2(7): e197178.

Baker, Allison M. and Linda M. Hunt. 2016. “Counterproductive Consequences of a Conservative Ideology: Medicaid Expansion and Personal Responsibility Requirements.” American Journal of Public Health 106(7): 1181-1187.

Berry, Diane S., James W. Pennebaker, Jennifer S. Mueller, and Wendy S. Hiller. 1997. “Linguistic Bases of Social Perception.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23(5): 526-537.

Bruch, Sarah K., Myra Marx Ferree, and Joe Soss. 2010. “From Policy to Polity: Democracy Paternalism and the Incorporation of Disadvantaged Citizens.” American Sociological Review 75(2): 205-226.

Campbell, Andrea Louise. 2007. “Universalism, Targeting and Participation.” In Joe Soss, Jacob S. Hacker, and Suzanna Mettler (eds.), Remaking America: Democracy and Public Policy in an Age of Inequality. Boston: MIT Press, 121-140.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. n.d. “1115 Transparency Requirements.” Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/1115- transparency-requirements/index.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

Dodge, Jennifer. 2015. “Indication and Inference: Reflections on the Challenge of Mixing Paradigms in the Narrative Policy Framework.” Critical Policy Studies 9(3): 361-367.

Epstein, Dimitry, Josiah Heidt, and Cynthia R. Farina. 2014. “The Value of Words: Narrative as Evidence in Policymaking.” Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1243. Available from: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1243 (accessed September 1, 2020).

Farina, Cynthia R., Dmitry Epstein, Josiah Heidt, Mary J. Newhart, and CeRI. 2012. “Knowledge in the People: Rethinking ‘Value’ in Public Rulemaking Participation.” Wake Forest Law Review 47: 1185-1241.

Fivush, Robin. 1991. “The Social Construction of Personal Narratives.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 37(1): 59-81.

Gilens, Martin. 1999. Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Golden, Marissa Martino. 1998. “Interest Groups in the Rule-Making Process: Who Participates? Whose Voices Get Heard?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8(2): 245-270.

Grogan, Colleen M., Phillip M. Singer, and David K. Jones. “Rhetoric and Reform in Waiver States.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 42(2): 247-284.

Guetzkow, Joshua. 2010. “Beyond Deservingness: Congressional Discourse on Poverty, 1964-1996.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 629(1): 173–197.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2004. The Politics of Disgust: The Public Identity of the Welfare Queen. New York: New York University Press.

Hinton, Elizabeth, MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, Larisa Antonisse, and Cornelia Hall. 2019. “Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: The Current Landscape of Approved and Pending Waivers.” Kaiser Family Foundation. 12 February 2019. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

Jarlenski, Marian, Philip Rocco, Renuka Tipirneni, Amy Jo Kennedy, Nivedita Gunturi, and Julie Donohue. 2017. “Shaping Health Policy for Low-Income Populations: An Assessment of Public Comments in a New Medicaid Waiver Process.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 42(6): 1039-1064.

Jones, Michael D. 2014a. “Comminicating Climate Change: Are Stories Better than ‘Just the Facts’?” Policy Studies Journal 42(4): 644-672.

—. 2014b. “Cultural Characters and Climate Change: How Heroes Shape Our Perceptions of Climate Science.” Social Science Quarterly 95 (1): 1–39.

Jones, Michael D. 2018. “Advancing the Narrative Policy Framework? The Musings of a Potentially Unreliable Narrator.” Policy Studies Journal 46(4): 724-746.

Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. 2018. “Monthly Membership Counts by County.” 6 August 2018. Available from: https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dms/stats/KDWMMCounts20180Aug.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

Kentucky Educational Television (KET). 2019. “Andy Beshear Victory Speech: 2019 General Election.” 5 November 2019. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5TJJOIf26k (accessed September 1, 2020).

Lejano, Raul P. 2015. “Narrative Disenchantment.” Critical Policy Studies 9(3): 368-371.

McBeth, Mark K., Donna L. Lybecker, and James W. Stoutenborough. 2016. “Do Stakeholders Analyze Their Audience? The Communication Switch and Stakeholder Personal Versus Public Communication Choices.” Policy Sciences 49: 421-444.

Mead, Lawrence M. 2011. “Welfare Politics in Congress.” PS: Political Science & Politics 44 (2): 345-356.

Meanwell, Emily and Julie Swando. 2013. “Who Deserves Good Schools? Cultural Categories of Worth and School Finance Reform.” Sociological Perspectives 56(4): 495-522.

Merry, Melissa K. 2016. “Constructing Policy Narratives in 140 Characters or Less: The Case of Gun Policy Organizations.” Policy Studies Journal 44(4): 373-395.

—. 2020. Warped Narratives: Distortion in the Framing of Gun Policy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Mettler, Suzanne and Jeffrey M. Stonecash. 2008. “Government Program Usage and Political Voice.” Social Science Quarterly 89(2): 273-293.

Michener, Jamila. 2018. Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Misra, Joya, Stephanie Moller, and Marina Karides. 2003. “Envisioning Dependency: Changing Media Depictions of Welfare in the 20th Century.” Social Problems 50(4): 482-504.

Musumeci, MaryBeth, Robin Rudowitz, and Elizabeth Hinton. 2018. “Re-approval of Kentucky Medicaid Demonstration Waiver.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 29 November 2018. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/re-approval-of-kentucky-medicaid-demonstration-waiver/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

Pennebaker, James W. 1997. Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions. New York: Guilford.

Peterson, Holly and Michael D. Jones. 2016. “Making Sense of Complexity: The Narrative Policy Framework and Agenda Setting.” In Nikolaos Zahariadis (ed.), Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 106-131.

Rose, Max and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2013. “Framing the Poor: Media Coverage and U.S. Poverty Policy, 1960–2008.” Policy Studies Journal 41(1): 22-53.

Rosenbaum, Sara. 2019. “‘We Have All Seen This Movie Before’: Once Again, a Federal Court Vacates HHS Approval of a Medicaid Waiver Experiment.” Health Affairs 2 August 2019. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190801.892432/ full/ (accessed September 4, 2020).

Schickel, John. 2018. “KY HEALTH, Part of State’s Medicaid Program, Means Able-Bodied Recipients Contribute.” Northern Kentucky Tribune, 30 June 2018. Available from: https://www.nkytribune.com/2018/06/john-schickel-ky-health-part-of-states-medicaid-program-means-able-bodied-recipients-contribute/ (accessed September 5, 2020).

Schneider, Anne L. and Helen M. Ingram. 1993. “Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy.” The American Political Science Review 87(2): 334-347.

Seccombe, Karen, Delores James, and Kimberly Battle Walters. 1998. “‘They Think You Ain’t Much of Nothing’: The Social Construction of the Welfare Mother.” Journal of Marriage and Family 60(4): 849–865.

Shanahan, Elizabeth A., Michael D. Jones, and Mark K. McBeth. 2018. “How to Conduct a Narrative Policy Framework Study.” The Social Science Journal 55(3): 332-345.

Shanahan, Elizabeth, Michael D. Jones, Mark K. McBeth, and Claudio Radaelli. 2017. “The Narrative Policy Framework.” In Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier (eds.), Theories of the Policy Process, 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 173-213.

Shildrick, Tracy and Robert MacDonald. 2013. “Poverty Talk: How People Experiencing Poverty Deny Their Poverty and Why They Blame ‘The Poor.’” The Sociological Review 61(2): 285–303.

Sievers, Tjorven and Michael D. Jones. 2020. “Can Power Be Made an Empirically Viable Concept in Policy Process Theory? Exploring the Power Potential of the Narrative Policy Framework.” International Review of Public Policy 2(1): 90-114.

Skocpol, Theda. 1991. “Targeting within Universalism: Politically Viable Policies to Combat Poverty in the United States.” In Christopher Jencks and Paul E. Peterson (eds.), The Urban Underclass. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 411–436.

Stewart, Cara and Sidney D. Watson. 2019. “Giving Voice to Medicaid: Waivers, Public Comments, and Kentucky’s ‘Secret Sauce.’” American Journal of Law & Medicine 45: 202-223.

Stryker, Robin and Pamela Wald. 2009. “Redefining Compassion to Reform Welfare: How Supporters of 1990s US Federal Welfare Reform Aimed for the Moral High Ground.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 16(4): 519–557.

Weible, Christopher M., Kristin L. Olofsson, Daniel P. Costie, Juniper M. Katz, and Tanya Heikkila. 2016. “Enhancing Precision and Clarity in the Study of Policy Narratives: An Analysis of Climate and Air Issues in Delhi, India.” Review of Policy Research 33(4): 420-441.

Willen, Sarah S. 2012. “How Is Health-Related ‘Deservingness’ Reckoned? Perspectives from Unauthorized Im/Migrants in Tel Aviv.” Social Science & Medicine 74(6): 812-821.

Yackee, Jason and Susan Yackee. 2006. “A Bias Towards Business? Assessing Interest Group Influence on American Bureaucracy.” The Journal of Politics 68(1): 128-139.

Zanocco, Chad, Geoboo Song, and Michael D. Jones. 2018. “Fracking Bad Guys: The Role of Narrative Character Affect in Shaping Hydraulic Fracturing Policy Preferences.” Policy Studies Journal 46(4): 978-999.

Chapter Appendixes

Appendix A. Content Analysis Categories

| Attribute | Description | Content Analysis Method | Examples of Words and Phrases | |

| Narrative Elements | Beneficiary | An individual or group receiving a benefit (either in the past, present, or future) (adapted from Weible et al. 2016) | Manual | Medicaid saved my life |

| Hero | An individual or group credited for taking action to solve a problem or for engaging in positively constructed behavior (adapted from Shanahan et al. 2017) | Manual | caregiver, hardworking people | |

| Victim | An individual or group subject to harm (either in the past, present, or future) (adapted from Weible et al. 2016) | Manual | I would lose my coverage | |

| Villain | An individual or group blamed for wrongdoing (adapted from Merry 2016) | Manual | Bevin is evil, wealthy legislators | |

| Setting | Reference to a geographic area impacted by a policy or a policy proposal | Automated

(dictionary created by authors) |

Appalachia, my city,

rural area, where we live |

|

| Solution | An enacted policy, a provision of an enacted policy, a policy proposal, or a provision of a policy proposal (adapted from Merry 2016) | Manual | Medicaid, premiums, work requirement, these changes | |

| Non-Narrative Elements | Research | Reference to research, data, or empirical evidence | Automated

(dictionary created by authors) |

research, data, evidence, studies show, poverty rate |

| Medical Knowledge | Reference to medical knowledge | Manual | dental issues can lead to infection | |

| Quantifying Language | Use of quantifiers | Automated

(internal LIWC dictionary) |

few, majority, multiple, every, single |

Appendix B. Characters in Public Comments on Kentucky HEALTH : Percentages of Comments Portraying Medicaid Consumers as Various Character Types

Percentages of Comments Portraying the Most Commonly Appearing Individuals and Groups as Various Character Types, Excluding Medicaid Consumers

Percentages of Comments Portraying the Most Commonly Appearing Individuals and Groups as Various Character Types, Excluding Medicaid Consumers

Appendix C. Policy Solutions in the Public Comments on Kentucky HEALTH

| Policy Solution or Provision | # of Comments | % of Total Comments |

| Medicaid (General) | 434 | 39.5 |

| Kentucky HEALTH (General) | 286 | 26 |

| Community engagement (80/month of work or

volunteering) |

317 | 28.8 |

| Reporting requirements | 157 | 14.3 |

| Dental benefits | 106 | 9.6 |

| Vision benefits | 83 | 7.5 |

| My Rewards (a program to earn credit toward dental

and vision benefits) |

9 | 0.8 |

| Lockouts (a 6-month lockout of coverage for failure to

meet requirements) |

41 | 3.7 |

| Premiums | 45 | 4.1 |

| Co-pays | 25 | 2.3 |

| Transportation Assistance | 39 | 3.5 |

| Penalties for unnecessary ER utilization | 11 | 1 |

| Retroactive eligibility | 7 | 0.6 |

[1] Following Stewart and Watson (2019), we use the term “Medicaid consumer” rather than “recipient” or “beneficiary.” This term is value-neutral and avoids confusion with the use of the term “beneficiary” as a character type in the Narrative Policy Framework.

[2] Prior to coding the random sample, we engaged in several rounds of test coding and discussion to ensure consistency in the content analysis. Each comment was then coded by one person.

[3] Given that advocates comprised such a small number of commenters, we excluded them from our analyses.

[4] See Appendix A for descriptions of content analysis categories.

[5] Rather than a problematic feature of the data, this imbalance represents a rare opportunity to examine the narrative strategies of infrequent policy actors (i.e., low income individuals). Future research should, however, explore the narratives of those who support restricting Medicaid and to assess whether narrative strategies vary as a function of policy position.

[6] See Appendices B and C for frequencies of specific characters and solutions.

[7] A Pearson’s chi-square test indicated that past Medicaid consumers were significant more likely to mention beneficiaries (χ2 = 24.781, p < 0.01) and less likely to mention victims (X2 = 18.841, p < 0.01) than other types of commenters.

[8] A Pearson’s chi-square test indicated that current Medicaid consumers were less likely than other commenters to use villains (χ2 = 23.501, p < 0.01), while unidentified commenters were more likely to mention villains (χ2 = 22.591, p < 0.01).

[9] A Pearson’s chi-square test indicated that current Medicaid consumers were less likely than other commenters to use setting (χ2 = 19.976, p < 0.01), while service providers were more likely to use setting (χ2 = 14.739, p <0 .01).

[10] Two-sample t-tests indicated that mean differences in narrative density were statistically significant for service providers (t = 4.2, p <0.01) and for commenters classified as “other relationship” to Medicaid consumer (t = 1.97, p = 0.05).

[11] A Pearson’s chi-square test indicated that service providers were more likely than other types of commenters to mention research (χ2 = 7.7388, p < 0.01). Likewise, service providers were more likely (χ2 = 26.917, p < 0.01) and current Medicaid consumers were less likely (χ2 = 6.64, p < 0.01) than other types of commenters to draw on medical knowledge.

[12] Pearson’s chi-square tests indicated that current consumers (χ2 = 15.111, p < 0.01) and past Medicaid consumers (χ2 = 7.569, p < 0.01) were less likely than other types of commenters to use quantifying language, while service providers (χ2 = 7.6502, p < 0.01) and unidentified commenters (χ2 = 5.517, p = 0.02) were more likely to use quantifying language.