C1: Understanding Technological Adaptability

Technological adaptability is a skill that is separate from but intertwined with technology skills. When I started teaching students to be technologically adaptable, I did not understand what was happening. I knew that students in my field must be able to learn technology quickly. I knew that I became adaptable by learning multiple programs in a short period of time. For years, I observed students learning technology. Slowly, I understood that something was happening beyond learning technology. My students were learning a skill that was intertwined with technology skills but is a skill in and of itself that must be continually honed and practiced.

Why Teach or Learn Technological Adaptability?

In January of 2023, a National Federation of Independent Businesses survey found that 91% of employers say they cannot find skilled employees. Often, this lack of skills falls into a technological area. Technology skills are required in fields that have not necessarily been associated with technology before, such as teaching or banking. For those who plan on working in any part of the technology sector, high-level training in technological adaptability is a must—even for accountants and administrative assistants.

Adaptability is not a fad. I can make one promise regarding technology and careers: it will change. We are now looking at a future filled with artificial intelligence, augmented reality, virtual reality, the Internet of Things, etc. Each of these can potentially create drastic changes in how we do business and interact with the world. Individuals who are not technologically adaptable may soon find themselves out of a job or struggle to participate in the world around them.

Goals

The primary goal of this workbook is to remove the fear of tackling new technologies so readers can develop skills for approaching a new technology or software package. A secondary goal is to teach readers skills that assist with technological adaptability, what I call sub-skills. After working through this book, some people will easily adapt to new technology; others may still struggle. Everyone can find it at least somewhat easier to adapt to new technological situations. This workbook will not make you a technology expert. However, you will expand your technology skills no matter your starting level. Additionally, you will gain beginner-level experience with the software we will be exploring. Such experience looks good on any resume.

You may find this course quite challenging. I encourage you to keep moving through it and keep trying. Many individuals find that something “clicks” when they keep pressing through any resistance they may feel. The most crucial factor is finishing the course, even if you must slog through it.

This workbook lays out exercises that teach professional-level adaptability. Since these exercises were originally created for professional and technical writing students, they are ideal for those fields but will work as well with graphic designers, trainers, usability experts, instructional designers, and the like. With a slight shift in focus, these exercises will work for many other fields and the general public.

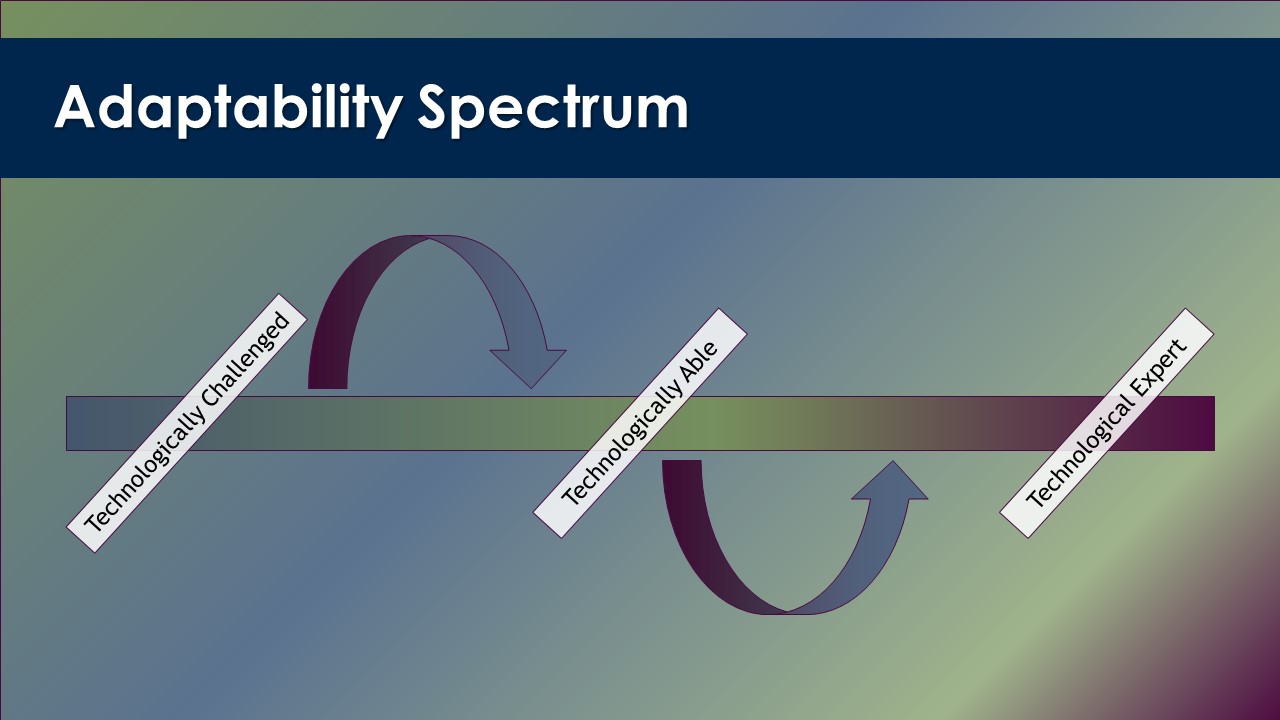

Adaptability Spectrum

Technological adaptability happens on a spectrum: from the technologically challenged to the technological expert. To actually become a technological expert will take years of practice. A single course or workbook will not take someone from being technologically challenged to being a technological expert, but wherever an individual is, it will move them down the spectrum toward true adaptability. And more importantly, it will give you the basic skills you need to continue becoming adaptable.

How is Technological Adaptability Different from Technological Literacy?

I have been asked if technological adaptability is just another name for technological literacy. Technological adaptability is interrelated with technological literacy. How and to what degree depends on the definition of technological literacy used and the focus of the technological literacy program. Since entire articles and books are written just on defining technological literacy, this comparison can be a bit daunting. Let us just consider one definition: the International Technology Education Association (2000) says technological literacy is “the ability to use, manage, understand, and assess technology.” In their definition, technological adaptability is deeply intertwined with technological literacy. Other definitions involve topics like being a good digital citizen, which is outside of the purview of technological adaptability.

At a low level, technological adaptability is a vital part of technological literacy and is needed for the average citizen living in a technological environment. However, at a higher level, the level of this course, technological adaptability is a step beyond literacy.

I am still looking for a tech literacy program that teaches adaptability, though one may exist. It appears that most technological literacy programs teach technology hoping that adaptability develops, which does for some students. I find that it works better if I teach adaptability, hoping that they will learn something about the technology.

Mark Pretsky developed the terms digital native and digital immigrant: those born into a technological world and those who have had to adjust to it. We have watched the baby boomers, who are digital immigrants, struggle with adopting technology for the most part. We tend to believe that digital natives will continue to be adaptable to new technologies. However, as those who have been involved with computers since their teens and twenties are now entering their older years, I find that they are perceived as less adaptable and are proving to be somewhat less adaptable. Even individuals who have been steeped in technology may find themselves unemployable if they do not show adaptability.

Tech-Savvy

If you are young and tech-savvy, do you need adaptability training?

Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, reflects many peoples’ attitudes toward technology by saying:

I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

I would add anything invented after you are fifty is from the devil and has come to destroy society.

If we do not continue to practice adaptability, we lose that skill. From what I have observed, some older millennials are starting to show a lack of adaptability to new skills. We will know for certain when a big change comes, say the adoption of augmented reality or virtual reality in the everyday workplace. Even people who work with technology daily can lose their ability to adapt if they infrequently work with new technology. Adaptability is a skill in and of itself that must be continually honed and practiced. So, yes, even tech-savvy individuals need to work on adaptability.

Background

So, how did this course come about, and why do I teach it as I do?

I was a technical communicator in the high-tech industry for over a decade. I worked primarily in the 1990s in Austin, Texas, when personal computing technology was relatively new and quickly changing. My primary job tended to be desktop publishing, so I had to keep up with all the advancements in the many types of software available. At that time, Microsoft and Adobe had yet to claim so much of the market share; we had quite a variety of software. I constantly had to learn a new program or adjust to a significant software package revision.

In 2003, I decided to pursue my Ph.D. to teach technical writing. I was dismayed to discover that most technical communication programs taught few, if any, software skills to students—students who would be dealing with technology their entire careers. When I asked why, I was told three reasons:

- If we taught technology like we teach other subjects where we are experts, it would take too much time to be a technology expert.

- Whatever we teach today will be outdated in a brief period.

- We do not know what technology students will face when they leave the classroom.

These statements are true, yet I knew from experience that these students desperately needed technical skills to succeed in their profession.

I realized I needed to teach the skill of learning technology quickly. But how would I do that? I could not find anyone who had ideas on how to teach this way, so I tried an experiment with one of my classes. I moved them very quickly through many software packages. In fact, the original class attempted 12 software packages in 15 weeks. It worked. By the end of class, students were comfortable approaching new technology, sometimes even very complicated technologies. They had more confidence in themselves and their technological abilities, knowing that they could figure out most issues on their own. As I continued to teach such skills, I honed the process. The result of that work is this book on technological adaptability.

With a bit of work, you, too, will have more skills in learning technology. It takes time and effort, but it is time and effort well spent. So, what do we need to begin our journey to technological adaptability? The next section will start your technological adaptability journey.

Beliefs

Belief and attitude play a big part in technological adaptability. Certain beliefs can stifle a person’s ability to learn technology. For example, some people believe that you are either technically inclined or not. I do think that some individuals find it easier to interact with technology, but anyone can become better with technology if they are willing to try. Willingness is the key to this issue.

I often run into people who want to take a short workshop and walk out adaptable. That simply does not happen. Most people are not willing to commit the time and effort to become adaptable unless their livelihood depends upon it.

Finally, some people believe that only younger people can learn technology. Younger brains are more malleable and do find it easier to learn just about anything. Yet, I have had several students that ranged in age from their 30s to their 60s and have succeeded in completing this course. Their biggest challenge has been adjusting to active learning, engaging students with projects or discussion, since they are more accustomed to rote learning, using memorization and repetition.

Holding on to these beliefs can limit a person’s ability to become adaptable. If you are holding on to any of these beliefs, I encourage you to let them go quickly. They will only make becoming adaptable harder.

Skill and Attitude

Technological adaptability is both a skill and an attitude. Gaining the skill of adaptability requires about as much effort as learning a musical instrument or perfecting a craft. For the skill part, this workbook will start you on learning, but truly becoming adaptable will require months and possibly even years of practice. Staying adaptable requires lifelong practice. However, you can adopt an attitude of adaptability today. An adaptable attitude is made up of many elements.

Can-Do Approach

My friend Jennifer says, “Your brain doesn’t want you to be a liar.” After teaching for over a decade, I believe this wholeheartedly. I have watched many students tell themselves they cannot do something, then subconsciously sabotage themselves. We fulfill our own prophecies. So, if our subconscious believes what we tell it, we must tell it positive things.

Watch for how you talk to yourself about your technical skills. Beware of thoughts like, “I’ll never be technical,” “I just don’t think that way,” or “I can’t do this.” When you catch yourself saying such things to yourself, stop and tell yourself, “I’ve got this.” Repeatedly. Even if you feel like you are lying to yourself, say it over and over and over again. “I can do this,” “I can think technically,” and “I am technologically adaptable” are phrases that will support this attitude and this process.

What I know is that you are not lying to yourself. Everyone has it in them to be somewhat technologically adaptable. Some of you will find it easier than others, but everyone can get better at the skill part with the right attitude.

There is a Solution

For almost any issue you face technologically, there is a solution. Occasionally, you may run into a problem that requires solving by an IT individual or by the company that created the software. However, chances are that you will be able to solve the issue with some creativity. We tend to think of creativity in the realm of art: writing, drawing, crafts, etc. Creative thinking can help tremendously when dealing with technological issues as well. We draw from our creativity by trying to think outside the box, thinking unconventionally, and getting inventive.

Play and Explore

One of the primary actions that helped me become adaptable was using my free time to play with and explore technology. I would open new programs and try to do something with them. I would take programs I knew and look at tools or menu items I seldom used. For example, when I had downtime, I would play with Photoshop filters or some of the more obscure Illustrator tools. When it came time to handle a project that needed such elements, I knew where to find them.

It can be hard to cultivate the play and explore attitude when you have time constraints, which seems to be standard for most of us these days. However, it can be worth putting the time aside to play and explore technology.

Just a note on play, video games will help you become more adaptable. However, they will make you really adaptable to new video games and just a little more adaptable to other technology. I will talk about this compartmental effect more in the exercises lecture.

Fear and Courage

For people who struggle with technology, the primary issue is fear. This fear might be quite subtle. It may be hard to recognize as fear. However, chances are fear is the problem if you really struggle with technology. Fear comes in many forms. It may look like being scared you will mess up the computer. It may look like a fear of looking stupid. It may be the fear of just not being skilled. It may be Impostor Syndrome: the belief that you are just not capable or worthy. It may be much more subtle and hidden. However, fear is often at the center of our issues.

The solution to fear is courage. Remember that courage does not mean you are not afraid; courage means you do it anyway. Each time you face these fears and step into them—each time you ignore that voice that says you cannot do this and do it any way—that fear will grow a little weaker, and your comfort with technology will grow a little stronger. By the end of the semester, many of my students are past the fear and truly believe they can be adaptable when needed.

|

The Impostor Syndrome, a term coined by Clance and Imes in 1978, refers to that fear of being exposed as a fraud, that if people really knew us, they would know we do not belong in that school, that job, wherever. Many of us deal with this belief in multiple situations, but I often see it in students working with technology. They have a hard time believing that they have technical skills, even when finishing exercises easily. |

Start with a good attitude and your skills will grow. Even if you struggle with the technology itself, continue to practice an adaptable attitude. It will help in the end.

Subskills

Though it will take you time to learn to be adaptable, you can learn some subskills quickly. These subskills will help you become adaptable faster than just trying to be adaptable alone. Each of the subskills you are learning can be sorted into three categories:

- Extrapolation: the ability to take information and adjust it to current needs, to take something not quite right and make it fit your requirements.

- Exploration: the willingness to search, investigate, and examine technology to understand it.

- Pattern Recognition: the ability to see similarities, familiar sequences, or common structures, creating an intuitive ability to find tools and options.

If you cultivate these subskills, you will find learning new technology and dealing with technological issues a bit easier.

Rote Learning vs. Adaptability Practice

We normally teach technology skills by rote practice, using memorization and repetition. Adaptability practice requires more exploration and investigation. Both practices have benefits and limitations.

Teaching by rote is a passive learning process. Students take in information and then produce a project or take a test over that information. Active learning requires a student figure things out on their own with some guidance and help.

Rote learning is very thorough; whereas, adaptability practice is spotty. To learn the details of a program, rote learning is much more effective.

Rote learning teaches hard skills; whereas, adaptability practice teaches soft skills. Both are valuable in their own way. We will learn more about these concepts in a moment.

Teaching by rote does nothing to address new technologies and new challenges. In taking a technology class taught by rote, the individual learns that technology. When taking an adaptability class, the individual learns a way to approach any new technology. Additionally, a technologically adaptable individual will learn more quickly when being taught by rote. Technological adaptability enhances teaching by rote; the ideal situation is teaching a combination of rote learning and adaptability skills.

You are most likely familiar with being taught by rote. Adaptability practice takes a new and different approach, one that requires active learning—you must take a key role in the process. This type of learning may feel uncomfortable, but I encourage you to do your best to immerse yourself in the experience. If you think, “She’s not teaching me anything,” realize that you are focused on learning technology and not learning technological adaptability.

|

Rote Learning |

Adaptability Practice |

|

Memorization and repetition |

Exploration and investigation |

|

Passive learning |

Active learning |

|

Thorough |

Spotty |

|

Teaches hard skills |

Teaches soft skills |

|

Finite skill potential |

Infinite skill potential |

Soft Skills vs. Hard Skills

Technological adaptability is a soft skill, whereas, technological know-how is a hard skill. By their very nature, they are intertwined. As a hard skill, we gain technical expertise and knowledge. We know a particular software inside and out. As a soft skill, we focus on attitudes, practices, and behaviors; we focus on what we think about technology, how we approach new technology, and how we learn to learn.

Technology skills are objective, tangible and quantifiable. We can test someone’s knowledge and skill with a program. Soft skills are subjective, intangible, and hard to measure. It takes someone who is adaptable to assess another’s adaptability.

Hard skills are hard to transfer. Knowledge of one program does not automatically lead to ease of learning another. Soft skills are transferable. We can take them into any technological situation.

Both the hard skill of technical expertise and the soft skill of adaptability are important. This course will focus on providing that soft skill of adaptability, but you will glean some technical knowledge along the way.

|

Hard Skills |

Soft Skills |

|

Technical expertise and knowledge |

Attitudes, practices, and behaviors |

|

Objective, tangible, and quantifiable |

Subjective, intangible, and hard to measure |

|

Hard to transfer |

Transferable |

The Process of Learning

Becoming technologically adaptable can be an uncomfortable process. Having taught this course for so long, I have finally decided that it just might be creating new neural networks in students’ brains. I have no evidence of that, but something changes in how a student thinks—and it can be an uncomfortable process.

It can mess with your thinking. You might become befuddled or absent-minded easily. You might have to stop and think about what you are doing more often.

You might find yourself having some uncomfortable emotions, being short-tempered or upset easily. The really tricky emotional response is apathy. A number of students failed or dropped my course because they let that one get the better of them.

Finally, it can infiltrate your subconscious. You might find yourself dreaming about the software or having images of the software constantly sitting in your mind. I was working with a woman who was learning a new software package that used the escape key before each command. I heard her answer the phone in a cheery voice: “Escape print! I found myself trying to turn off my alarm one morning by saying “Control Q! Control Quit!”

These effects are temporary. They usually show up at the second or third technology practice, though they may only show up during this beginner course if we are taking it slowly. Most people find that they go away within a month to six weeks. For many students, something just clicks and, from then on, the uncomfortable effects are gone, and they find learning a new software quite easy. Even those who do not get the click still find that these effects diminish to little or nothing and working with new software becomes easier.