13 – Collaborative Writing

Collaborative Writing Processes

Suzan Last; Candice Neveu; Kalani Pattison; Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt; and Matt McKinney

Collaborative projects are common in many fields and disciplines, as individuals with various realms of expertise work together to accomplish goals and create projects. Writing is a key part of communication that enables these projects to happen, but it also is often the deliverable—the final product that a team can pass on to another team, to executives and administrators, to consumers, or to the public. Working as a team to write a document usually means that each individual writes less content. However, to create a coherent document written in one voice, teams must plan carefully and revise thoughtfully.

The following section examines in more depth how writing in general, and collaborative writing specifically, is crucial to engineering. Engineering is a field that is often perceived as entailing a relatively small amount of writing. However, as you will see in this following section, such perceptions are often misinformed. The same misperceptions may also take place regarding other fields, so you should think about how this engineering-specific information might apply more widely to your discipline.

The engineering design process, at least in part, entails working collaboratively to gather, organize, manage, and distribute information.[1] This information is often carefully analyzed and used to make important decisions, so it is critical that team members collaborate effectively in managing these communications tasks.

Engineers report spending a considerable amount of their time writing, and they frequently engage in collaborative writing. A recent survey asked various professionals what portion of their work week was devoted to writing, collaborative writing, and international communications.[2] The results shown in Table 13.5 indicate that collaborative writing makes up a significant portion of overall writing tasks.

Table 13.5. Percentage of total work week that engineers and programmers report spending on communications tasks.

| Activity | % of Work Week for Engineers | % of Work Week for Programmers |

|---|---|---|

| Time spent writing | 35 | 25 |

| Time spent planning and writing documents collaboratively | 19 | 12 |

| Time spent communicating internationally (across national borders) | 14 | 18 |

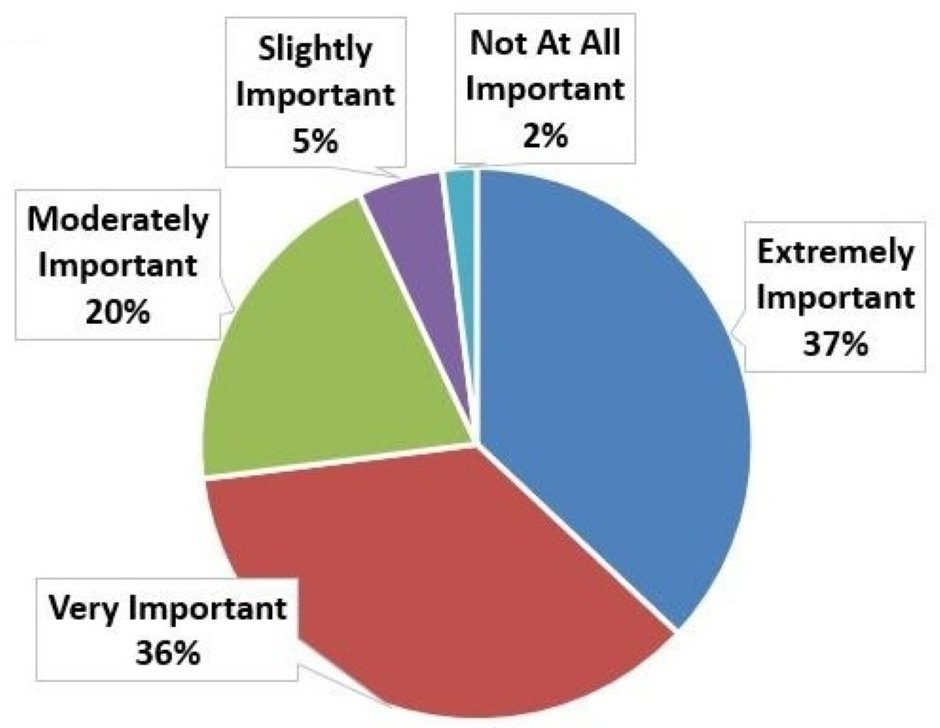

Research has also shown that “writing in general and [collaborative writing] in particular have been recognized to be fundamental to most professional and academic practices in engineering.”[3] Figure 13.4[4] shows that engineers rate writing skills as extremely important to career advancement.[5]

Like any kind of teamwork, collaborative writing requires the entire team to be focused on a common objective. According to Lowry et al., an effective team “negotiates, coordinates, and communicates during the creation of a common document.”[6] The collaborative writing process is iterative and social, meaning the team works together and moves back and forth throughout the process.

Collaborative Writing Stages and Strategies

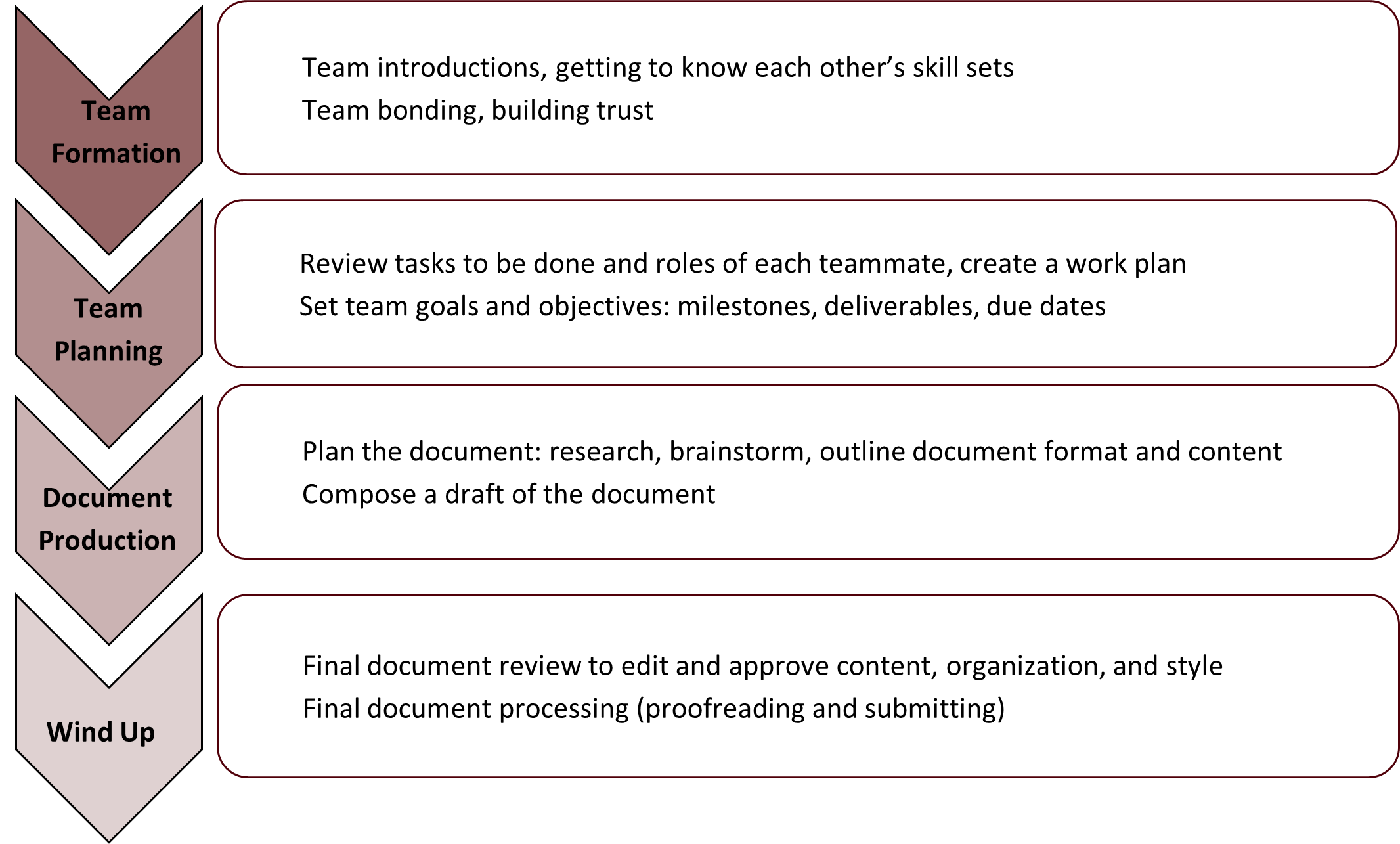

Successful collaborative writing is made easier when you understand the collaborative writing strategies you can apply, the best ways to manage a document undergoing revisions, and the different roles people can assume. Figure 13.5[7] outlines the various activities involved at various stages of the collaborative writing process.

Collaborative writing strategies are methods a team uses to coordinate the writing of a collaborative document. There are five main strategies: single-author, sequential, parallel writing: horizontal division, parallel writing: stratified division, and reactive writing. Each strategy has its advantages and disadvantages. Effective teams working on longer term projects tend to use a combination of collaborative writing strategies for different points of the project. When planning to switch between writing strategies, it is important to make sure the team is communicating clearly regarding which strategy will be used for which task. See Table 13.6[8] for a detailed breakdown of these strategies, their advantages, and disadvantages. Can you think of any other benefits or limitations?

Table 13.6. Collaborative writing strategies.

| Writing Strategy | When to Use | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Author

One member writes for the entire group. |

For simple tasks; when little buy-in is needed; for small groups | Efficient; consistent style | May not clearly represent group’s intentions; less consensus produced |

| Sequential

Each member is in charge of writing a specific part and write in sequence. |

For asynchronous work with poor coordination; when it’s hard to meet often; for straightforward writing tasks; small groups | Easy to organize; simplifies planning | Can lose sense of group; subsequent writers may invalidate previous work; lack of consensus; version control issues |

| Parallel Writing: Horizontal Division

Members are in charge of writing a specific part but write in parallel. Segments are distributed randomly. |

When high volume of rapid output is needed; when software can support this strategy; for easily segmented, mildly complex writing tasks; for groups with good structure and coordination; small to large groups | Efficient; high volume of output | Redundant work can be produced; writers can be blind to each other’s work; stylistic differences; doesn’t recognize individual talents well |

| Parallel Writing: Stratified Division

Members are in charge of writing a specific part but write in parallel. Segments are distributed based on talents or skills. |

For high volume, rapid output; with supporting software; for complicated, difficult-to-segment tasks; when people have different talents/skills; for groups with good structure and coordination; small to large groups | Efficient; high volume of quality output; better use of individual talent | Redundant work can be produced; writers can be blind to each other’s work; stylistic differences; potential information overload |

| Reactive Writing

Members create a document in real time, while others review, react, and adjust to each other’s changes and additions without much preplanning or explicit coordination. |

Small groups; high levels of creativity; high levels of consensus on process and content | Can build creativity and consensus | Very hard to coordinate; version control issues |

Document management reflects the approaches used to maintain version control of the document and describe who is responsible for it. Four main control modes (centralized, relay, independent, and shared) are listed in Table 13.7, along with their pros and cons. Can you think of any more, based on your experience?

Table 13.7. Document control modes.

| Mode | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized | When one person controls the document throughout the process | Can be useful for maintaining group focus and when working toward a strict deadline | Non-controlling members may feel a lack of ownership or control of what goes into the document |

| Relay | When one person at a time is in charge but the control changes in the group | Democratic | Less efficient |

| Independent | When one person maintains control of their assigned portion | Useful for remote teams working on distinct parts | Often requires an editor to pull it together; can reflect a group that lacks agreement |

| Shared | When everyone has simultaneous and equal privileges | Can be highly effective; non-threatening; good for groups working face to face, who meet frequently, who have high levels of trust | Can lead to conflict, especially in remote or less functional groups |

Roles refer to the different duties participants might undertake, depending on the activity. In addition to whatever roles and responsibilities that individual team members performed throughout other stages of the project, the actual stages of composing and revising the document may require writing-specific roles. Table 13.8 describes several roles within a collaborative writing team. Members of small teams must fill multiple roles when prewriting, drafting, and revising a document collaboratively. Which role(s) have you had in a group project? Are there ones you always seem to do? Ones that you prefer, dislike, or would like to try?

Table 13.8. Collaborative writing roles.

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Writer | A person who is responsible for writing a portion of the content |

| Consultant | A person external to the project and who has no ownership or responsibility for producing content, but who offers content and process-related feedback (peer reviewers outside the team; instructor) |

| Editor | A person who is responsible for the overall content production of the writer, and can make both style and content changes; typically has ownership of the content production |

| Reviewer | A person, internal or external, who provides specific content feedback but is not responsible for making changes |

| Project Manager | A person who is part of the team and may fully participate in authoring and reviewing the content, but who also leads the team through the processes, planning, rewarding, and motivating |

| Facilitator | A person external to the team who leads the team through processes but doesn’t give content related feedback |

This text was derived from

Last, Suzan, with contributors Candice Neveu and Monika Smith. Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Susan McCahan, Phil Anderson, Mark Kortschot, Peter E. Weiss, and Kimberly A. Woodhouse, “Introduction to Teamwork,” in Designing Engineers: An Introductory Text (Hoboken, NY: Wiley, 2015), 14. ↵

- Jason Swarts, Stacey Pigg, Jamie Larsen, Julia Helo Gonzalez, Rebecca De Haas, and Elizabeth Wagner, Communication in the Workplace: What Can NC State Students Expect? (Raleigh: North Carolina State University Professional Writing Program, 2018), https://docs.google.com/document/d/1pMpVbDRWIN6HssQQQ4MeQ6U-oB-sGUrtRswD7feuRB0/edit#heading=h.n2a3udms5sd5. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- Julio Gimenez and Juliet Thondhlana, “Collaborative Writing in Engineering: Perspectives from Research and Implications for Undergraduate Education,” European Journal of Engineering Education 37, no. 5 (2012): 471-487, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2012.714356 ↵

- Adapted from Jason Swarts, Stacey Pigg, Jamie Larsen, Julia Helo Gonzalez, Rebecca De Haas, and Elizabeth Wagner, Communication in the Workplace: What Can NC State Students Expect? (Raleigh: North Carolina State University Professional Writing Program, 2018), 5, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1pMpVbDRWIN6HssQQQ4MeQ6U-oB-sGUrtRswD7feuRB0/edit#heading=h.n2a3udms5sd5. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- Jason Swarts, Stacey Pigg, Jamie Larsen, Julia Helo Gonzalez, Rebecca De Haas, and Elizabeth Wagner, Communication in the Workplace: What Can NC State Students Expect? (Raleigh: North Carolina State University Professional Writing Program, 2018), 5, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1pMpVbDRWIN6HssQQQ4MeQ6U-oB-sGUrtRswD7feuRB0/edit#heading=h.n2a3udms5sd5. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- Paul Benjamin Lowry, Aaron M. Curtis, and Michelle René Lowry, “Building a Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Collaborative Writing to Improve Interdisciplinary Research and Practice,” Journal of Business Communication 41, no. 1 (2004): 66-97, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943603259363. ↵

- Adapted from Suzan Last and Candice Neveu, “Collaborative Writing Stages,” in “Collaborative Writing,” Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- Adapted from Suzan Last and Candice Neveu, “Collaborative Writing Strategies,” in “Collaborative Writing,” Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The original authors note that this table is adapted from Paul Benjamin Lowry, Aaron Curtis, and Michelle René Lowry, “Building a Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Collaborative Writing to Improve Interdisciplinary Research and Practice,” Journal of Business Communication 41, no.1 (2004): 66-97, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943603259363. ↵

Final product that a team can pass on to another team, to executives and administrators, to consumers, or to the public.

Collaborative writing strategy where collaborators create, review, and revise a document in real time, without much pre planning or explicit coordination.

Method of collaborative writing where collaborators work in parallel but distribute writing assignments based on talents or skills.

Method of collaborative writing where collaborators work in parallel but distribute writing assignments randomly.

Each member is in charge of writing a specific part and write in sequence.

One member writes for the entire group.

Person external to a team who leads the team through processes but doesn’t give content-related feedback.

A person on a team who acts as the hub for communication and tasks. This person helps provide direction and guidance for the team.

Person, internal or external, who provides specific content feedback but is not responsible for making changes.

Person responsible for the overall content production of the writer, who may make structure, style, and content changes.

Person external to a project who has no ownership or responsibility for producing content, but who offers content and process-related feedback.

Person who is responsible for writing a portion of the content.