15 – Correspondence

Annemarie Hamlin; Chris Rubio; Michele DeSilva; James Francis, Jr.; Matt McKinney; and Kalani Pattison

Email is familiar to most students and workers. It may be used like text or synchronous chat, and it can be delivered to a cell phone. In business, email has largely replaced print hard copy letters for external (outside the company) correspondence, and in many cases, it has taken the place of memos for internal (within the company) communication.[1] Email can be very useful for messages that have slightly more content than a text message, but it is still best used for fairly brief messages. Many businesses use automated emails to acknowledge communications from the public, or to remind associates that periodic reports or payments are due. You may also be assigned to “populate” a form email in which standard paragraphs are used, but you choose from a menu of sentences to make the wording suitable for a particular transaction.

Emails may be informal in personal contexts, but business communication requires attention to detail, awareness that your email reflects you and your company, and a professional tone so that it may be forwarded to any third party if needed. Email often serves to exchange information within organizations. Never write or send anything that you wouldn’t want read in public or in front of your company president.

Tips for Effective Business Emails

As with all writing, professional communications require attention to the specific writing context, and it may surprise you that even elements of form can indicate a writer’s strong understanding of audience and purpose. The principles explained here apply to the educational context as well; use them when communicating with your instructors and classroom peers.

Open with a proper salutation. Proper salutations demonstrate respect and avoid mix-ups in case a message is accidentally sent to the wrong recipient. For example, use a salutation like “Dear Mary Smith” (external) or “Hi Barry” (internal). Especially for internal communications, a polite greeting frames your message as a request rather than a demand.

If you do not know the recipient personally, never use titles such as Mrs., Ms., or Mr. as you cannot assume gender, marital status, or profession, such as “Dr.” “The Honorable” or “Rabbi” as name prefixes. If you do know the recipient, use their preferred form of address for your context and relationship. (For instance, if your professor has their doctorate and signs their emails Dr. Smith, then that is likely how they wish to be addressed). If the gender of a person and/or their personal pronoun use are not known, use their entire name like this: “Dear Sam Jones.”

Traditionally, salutations end with either a comma, colon, or exclamation point, depending on the formality and content of the message. All have their uses, but the most common in technical and professional communication will be the comma or the colon. The colon is typically reserved for more formal and external scenarios whereas the comma is used for everyday internal communications.

Include a clear, brief, and specific subject line. This helps the recipient understand the essence of the message. For example, “Proposal attached” or “Your question from 10/25.” Including an opening phrase such as “Action Item:” may be appropriate if there is a request with a specific deadline and you are in a position to give instructions to the recipient. Use the CC (carbon copy) and BCC (blind carbon copy) entries appropriately, depending on who needs to be included in the communication and/or copied to have access to the information.

Close with a signature. Identify yourself by creating a signature block that automatically contains your name and business contact information and aligns with your organization’s branding guidelines if applicable. Depending on your audience, consider including your gender identifying pronouns (particularly if you are cisgender) to normalize gender inclusivity in technical and professional communication and to help ensure you are addressed properly. However, if you are transgender or nonbinary, you are not obligated to do so if you find this transparency uncomfortable or risky.

Avoid text/internet slang. An email is not a text message, and the audience may not find your wit cause to ROFL.

Be brief. Omit unnecessary words.

Use clear formatting cues. Divide your message into brief paragraphs for ease of reading. A good email should get to the point and conclude in three small paragraphs or less.

Reread, revise, and review. Catch and correct spelling and grammar mistakes before you press “send.” It will take more time and effort to undo the problems caused by a hasty, poorly written email than to get it right the first time.

Reply promptly. Watch out for an emotional response—never reply in anger—but make a habit of replying to all emails within one business day, even if only to say that you will provide the requested information in 48 or 72 hours.

Use “Reply All” sparingly. Do not send your reply to everyone who received the initial email unless your message absolutely needs to be read by the entire group. Consider using the BCC option if writing to a group, as this will prevent “Reply All” from being accidentally used.

Avoid using all caps. Capital letters are used on the Internet to communicate emphatic emotion or yelling, and they are considered rude in professional settings.

Test links. If you include a link, test it to make sure it is working. In addition, if you are sending a link to a document saved on the cloud (such as OneDrive or Google Drive), make sure the permissions are set correctly.

Give feedback or follow up. If you don’t receive a response in two-to-three business days, email or call the original receiver. Spam filters may have intercepted your message, so your recipient may never have received it.

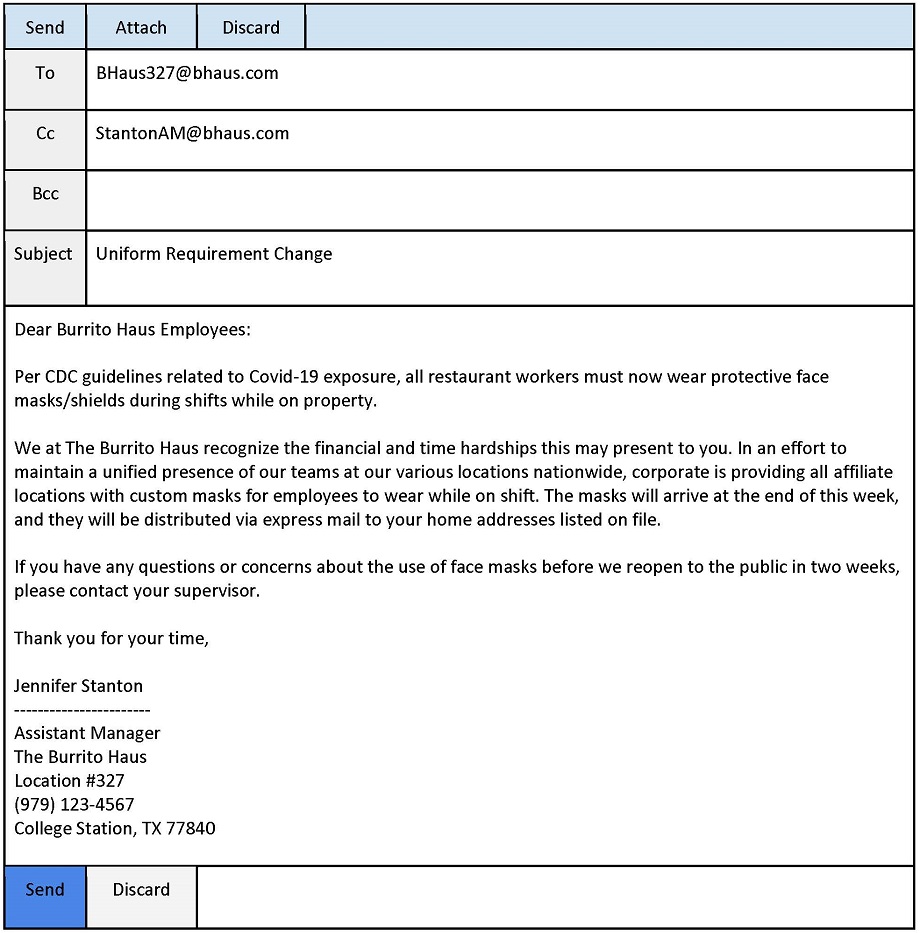

Figure 15.1[2] shows a sample email that demonstrates the principles listed above.

This text was derived from

Gross, Allison, Annemarie Hamlin, Billy Merck, Chris Rubio, Jodi Naas, Megan Savage, and Michele DeSilva. Technical Writing. Open Oregon Educational Materials, n.d. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The above authors derived their text from:

Saylor Academy. “PRDV002: Professional Writing.” April 2016. Online Course. https://learn.saylor.org/course/view.php?id=56. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

McMurrey, David. Online Technical Writing. n.d. https://www.prismnet.com/~hcexres/textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Mary E. Guffey, Essentials of Business Communication, 7th ed. (Mason, OH: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2008). See also Ingram Leedy, "Communication Tools Changed the Workplace (From Memos to Emojis)," Protected Trust Modern Workplace Blog, Feb. 4, 2020, https://blog.protectedtrust.com/communication-tools-changed-the-workplace. ↵

- James Francis, “Sample Email,” 2020. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵