Writing Critical Reviews

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

This chapter aims to help you build strong arguments in your own work by learning to write critical reviews, or critiques, of texts. A critical review requires a close examination of the argument presented in a text (analysis) and a subsequent explanation of how effective the argument is (evaluation). Critiques are assigned in both academic and technical writing classes because they encourage critical reading practices; in other words, this type of assignment calls for a sharp eye to discern what a piece says and how it communicates in order to arrive at a reasoned judgement about its argument. Ultimately, a critical review may discuss both the strengths and weaknesses of a document.

How might the skills used to develop a critical review be applicable in a workplace setting?

Understand Expectations before Starting a Critical Review Assignment

As with any assignment, make sure you understand the expectations for a critical review before beginning work on it. Pay attention to specifications regarding the paper’s audience, purpose, genre, and design; in addition, determine how many and what type of sources are required. You may be asked to restrict your evidentiary source list to the document under review rather than search for additional sources. Read the critical review directions carefully, and approach your instructor if you have unresolved questions.

Read a Text Closely to Prepare for a Critical Review

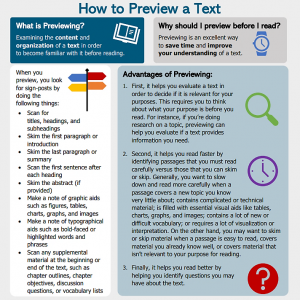

A critical review requires close engagement with a text: you cannot effectively analyze and evaluate a document if you have not read and attempted to comprehend it. To develop a broad understanding of a text’s focus and composition, begin by previewing the document. While other chapters of this textbook discuss previewing in detail, Figure 1, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020c), offers a reminder of how to undertake this activity.

Figure 1. How to preview a text before reading it in full

Previewing should give you an overall sense of what the text is about, how it is organized, and what information it contains.

After previewing the piece, it is time to read it though, while keeping the assignment purpose in mind. Because a critical review demands close work with a text, be prepared to annotate as you read by reflecting on the document’s content and meaning, recording comments and questions in the margin, highlighting important examples and evidence, underlining and defining new vocabulary, and making notes about your reactions to the text. These activities can facilitate understanding of and connection with a piece, aspects crucial to writing a successful critical review.

Your active engagement with the text should continue even after you have read it in full. To illustrate, you can use the prompts in Figure 2, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020a), to investigate the author’s intent for writing the document.

Figure 2. Prompts for evaluating an author’s intent

In addition to evaluating an author’s intent, think carefully about your own reactions to the text as a means to interrogate it further. The following questions, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020d) and Student Academic Success Services at Queen’s University (2018, “Strengths/Weaknesses”), may help in this regard.

- What, if anything, about the reading is unclear? Why is it unclear?

- Does the text deliver on the promises it made in its title and introduction?

- Do you find the author’s writing style persuasive? Why or why not?

- Are the author’s arguments logical? Do they make sense?

- Are points illustrated with relevant and comprehensible examples?

- What kind of evidence does the author provide to support claims? Given the purpose of the piece and its audience, is the evidence from suitable sources?

- Is the evidence relevant? Is it sufficient? Is it credible?

- Does the author supply stated or unstated reasons to support claims?

- Does the author consider alternative points of view, reasons, and evidence?

- How does the reading compare with other texts on the same topic?

- What ideas do you find most thought-provoking?

- What points do you want to investigate further?

The activities described here are intended to promote active engagement with a reading for purposes of eliciting a critical response to it.

Take Advantage of Opportunities to Discuss the Text

Discussions can sometimes inspire thoughtful reflection about a text and clarify lingering uncertainties, so seize opportunities to discuss the document with your classmates. If your instructor schedules a seminar or class discussion period to focus on the text, aim to get as much out of it as you can by preparing in advance, by contributing during the activity, and by reflecting on the experience afterward. Figure 3, adapted from McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph (n.d.), shares tips for participating in class discussions.

Can you think of any other advice you would add to the visual?

Figure 3. How to take part in class discussions

Always be respectful of others’ ideas during a class discussion to encourage a positive and productive session. Remember that one of the reasons to engage in discussion is to hear viewpoints different from your own—ultimately these viewpoints may help to refine your own understanding of the reading.

Meeting with your instructor to discuss the text might also help bring your own ideas into focus. Faculty members appreciate talking with students who take active steps to ensure their own success, so be sure to read the document prior to the appointment. Schedule the meeting with your instructor by sending an email that applies the best practices discussed in this textbook, and arrive on time to the session prepared with your questions. Figure 4, a multipage handout adapted from Roux et al. (2020), illustrates these pieces of advice.

Can you think of any other tips you would add to the visual?

How might the skills used to schedule and participate in a meeting with an instructor be transferred to a workplace context?

Figure 4. Tips for emailing and meeting with an instructor

Do not be afraid to discuss points of uncertainty or confusion during a meeting with an instructor. After all, your purpose is to seek clarification about a text so that you may write about it confidently in a critical review.

Understand How to Organize a Critical Review

Once you have read the text and feel confident about discussing it, you can make plans for your critical review. This type of paper generally follows an introduction, body, and conclusion structure, the same organizational configuration you have applied when writing memos and letters.

The Introduction

To establish context for readers, begin the introduction with a concise summary of the document under review; list the document’s title and author at the beginning of the summary. This summary serves as a foundation for the subsequent critical discussion of the text presented in the body section of the paper. Recall that when composing a summary, a writer uses his or her own words and sentence structures, focuses on main points, excludes details, and cites and references source material. The following summary, adapted from the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d., para. 4), demonstrates application of these summary guidelines.

In their article “British Columbia’s Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax: A Review of the Latest ‘Grand Experiment’ in Environmental Policy,” Murray and Rivers (2015) examine the outcome of that province’s first attempt to institute a carbon tax. The main goal was to try to lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Following principles favored by economists, the authors explain that the province began with a small tax and increased the rate over several years, allowing taxpayers to ease into the plan slowly. By reviewing other research studies and using a simulation model, Murray and Rivers (para. 1) find that GHG emissions decreased by 5 to 15 percent as a result of the carbon tax. This reduction was higher than expected, and the authors suggest that a carbon tax not only works because of the extra financial burden, but also because of some other social cost of consuming fossil fuels; however, the exact mechanism is not yet understood. Their study also revealed that public support for the carbon tax grew post-implementation.

Reference

Murray, B., & Rivers, N. (2015). British Colombia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax: A review of the latest ‘grand experiment’ in environmental policy. Energy Policy, 86, 674-683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.08.011

Notice how compact this summary is: it communicates the central points of a nine-page journal article in one concise paragraph.

After the summary, continue the introduction by supplying a thesis statement that reveals the critical review’s purpose and your determination regarding the effectiveness of the text’s argument: this determination is the result of your analysis and evaluation of the argument. The thesis may also outline the critique’s organization; alternatively, you might decide to place the forecasting statement (route map) in a separate sentence at the end of the introduction. The following introduction, adapted from Grosz (2019, paras. 1, 2, 3), demonstrates these elements at work in a sample critique introduction.

In his 2019 Harvard Data Science Review article entitled “Artificial Intelligence—The Revolution Hasn’t Happened Yet,” Michael I. Jordan makes evident that many have lost sight of the full richness of human intelligence and have neglected to separate foundational understanding from engineering. Most importantly, he points out the need to develop an “engineering discipline . . . for the data-focused and learning-focused fields” and that the systems based on their methods “should be built to work as claimed” (para. 29). A distinguished machine learning insider, Jordan speaks with authority, bringing insight to current discussions of the promise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the potential threats it raises for societal wellbeing. The article, nonetheless, misses two important pieces of the story: the point that when established, the AI and human-computer interaction fields initially competed to their detriment and the reality that humanities values and social science principles are central to the foundation of the engineering discipline he describes. I discuss these matters in turn and then indicate ways they should inform the engineering discipline Jordan envisions.

Reference

Jordan, M.I. (2019). Artificial intelligence—The revolution hasn’t happened yet. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.f06c6e61

Although the jargon used in this paragraph may be unfamiliar to you, the text’s organizational structure is nevertheless clear.

The Body

Organize your body paragraphs around the themes that resulted from your evaluation of the text. In other words, rather than discussing each paragraph of the text in a chronological fashion—an approach that can be wordy and repetitious—think about the main points that emerged during your examination of the text’s argument, and center your discussion on those areas. Your aim when writing a critical review is to construct an argument about the effectiveness of the text’s argument, so begin each body paragraph with a topic sentence that makes a claim in reference to an evaluation theme. Then develop the body paragraphs by discussing examples and evidence from the text to support your points; remember to indicate the relevance of this information to your argument and incorporate it cohesively into your text. The following student example, adapted from Jensen (2014) as cited in Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020f, “Sample Essay”), demonstrates these guidelines at work in a body paragraph.

In the article “Why I Won’t Buy and iPad (and Think You Shouldn’t, Either),” Cory Doctorow (2014) expresses bias against the digital rights management (DRM) control built into the Apple iPad’s design by constructing a one-sided argument. He makes the point that Apple “uses DRM to control what can run on your devices, which means that Apple’s customers can’t take their ‘iContent’ with them to competing devices, and Apple developers can’t sell on their own terms” (para. 13). Doctorow is a software creator, so he has something personal to gain from unconstrained digital media sharing; however, not everyone can develop software. The author overlooks the iPad’s beneficial applications, which can be used by a diverse range of people, by focusing only on those who are looking to develop and sell their own software. Just because the iPad does not work for Doctorow does not mean it will not work for others.

Reference

Doctorow, C. (2010, April 2). Why I won’t buy an iPad (and think you shouldn’t, either). BoingBoing. https://boingboing.net/2010/04/02/why-i-wont-buy-an-ipad-and-thi.html

Be sure to cite and reference pieces of evidence, including those taken from the text under review, as the sample does.

The Conclusion

When writing the conclusion section of a critical review, reiterate your thesis (without repeating it word for word) and emphasize what your analysis and evaluation reveals about the text under review.

Plan Your Critical Review

A well-organized critical review requires careful planning: although close work with a text can reveal many points about its argument, you will likely only be able to discuss a selection of these in your paper given length restrictions. An outline may help you to narrow the focus of your paper and devise a logical plan for its construction. Figure 5, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020e), provides tips for outlining.

Figure 5. Guidance for constructing an outline

A concept map, also known as a mind map, can also be used to plan a critical review. Figure 6, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020b), supplies directions for constructing a concept map.

Figure 6. Instructions for creating a concept map

Whatever planning method you select, concentrate only on prominent evaluation themes in order to address those themes adequately in your paper.

Use an Appropriate Tone and Language When Writing a Critical Review

A critical review aims to reveal the positive and negative aspects of a text’s argument in order to comment upon its effectiveness; in so doing, a critical review makes its own argument. As with other types of academic and technical writing, maintain a respectful, reasonable tone when writing a critique so that you work is taken seriously. Tone is the attitude a writer conveys toward a paper’s audience and subject matter. Strive to build your argument on clear claims, rational reasons, and quality evidence—as well as coverage of counter-claims, reasons, and evidence—rather than on emotive language, exclamatory sentences, personal attacks, or indefensible assertions. The latter weaken an argument’s persuasiveness and are inappropriate in academic and technical writing.

When writing a critical review, use words that are precise, concise, and appropriately formal. The following guidelines elaborate on these points.

Negative Sentence Construction

Avoid negative sentence constructions because they can be awkward and difficult to follow. Here is an example.

- Instead of: He did not remember to complete the homework assignment.

- Write: He forgot to complete the homework assignment.

The affirmative sentence construction provides a clear and concise alternative to the awkward first version.

Word Choice (adapted from McNamee, 2019, p. 1)

When writing for a technical or academic audience, avoid unquantifiable descriptive words, such as good, bad, great, huge, big, very, extremely, incredibly, and enormously. These words are problematic because they do not define a specific degree or amount.

Sentence Structure (adapted from McNamee, 2019, p. 2)

Aim to convey the meaning of a sentence, the key information, at the beginning of the sentence. To demonstrate, look at these two examples.

- Instead of: Despite the margins of error due to human error that occurred due to improper pipette cleaning, the results showed that the pH still remained acidic.

- Write: The results showed the pH remained acidic, despite the margins of error due to improper pipette cleaning.

The first version is unclear because the beginning clause does not communicate the main purpose of the sentence. The second version communicates the focus of the sentence early on and is also more concise.

Language (adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020g)

Make every effort to use language that is clear and appropriately formal when writing a critical review. Here are some specific guidelines to keep in mind.

- Avoid I think, I feel, I believe statements unless your instructor advises otherwise.

- o Instead of: I think anyone who becomes a parent should have to take parenting classes.

- o Write: Parenting classes should be mandatory for biological and adoptive parents.

- Avoid using the word you to refer to people in general.

- o Instead of: When you read this textbook, you will notice the content is focused on technical writing.

- o Write: Textbook readers will notice this book’s content focuses on technical writing.

- Avoid contractions.

- o Instead of: The study didn’t examine how age affected participants’ notetaking practices.

- o Write: The study did not examine how age affected participants’ notetaking practices.

- Avoid wordy, informal phrases.

- o Instead of: A lot of employees showed up at the staff meeting.

- o Write: Twenty-five employees attended the staff meeting.

- Avoid redundant words and phrases.

- o Instead of: The conference presentation was brief in length.

- o Write: The conference presentation was brief.

Consider the audience, purpose, context, and genre for a critique to gauge the level of formality expected in the document.

Can you think of any other tone or language tips you would add to this textbook section?

Activity A: Read and Work with a Text that Addresses Top Writing Errors

Read the handout “Top Twenty Errors in Undergraduate Writing” (Hume Center for Writing and Speaking, Stanford University, n.d.), which can be found at the following address.

Now review the feedback on three of your previous writing assignments. Do you detect any of the errors listed on the handout in your work? Identify three issues that recur in your assignments and handout sections/explanations that will help you address these issues.

Issue one + handout section/explanation:

Issue two + handout section/explanation:

Issue three + handout section/explanation:

Activity B: Read and Engage with a Formal Report

Watch a video entitled “Meet Emma – Your Work Colleague of the Future” (Fellowes Brands, 2019), which can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fL5SuzGkUPw, for an introduction to the topic of a particular formal report.

Now open William Higham’s (2019) formal report entitled “The Work Colleague of the Future: A Report on the Long-Term Health of Office Workers” at https://assets.fellowes.com/skins/fellowes/responsive/gb/en/resources/work-colleague-of-the-future/download/WCOF_Report_EU.pdf. You will be asked to write a critical review of Higham’s report for homework. To help you comprehend and connect with the ideas discussed in the report, practice preview, close, and critical reading techniques by following the steps listed. Actively engage with the text by making notes on the steps as you proceed.

- Preview the report.

- Look at the title of the text. Based on the title, what do you think the report is about?

- Look at the text’s headings and subheadings. What do these tell you about the topic of the report?

- Skim through the introduction. What do you expect the report will discuss?

- Skim though the final section of the report. What did you learn?

- What is your initial impression regarding the soundness of the report? What made you form that impression?

- Investigate the report’s author.

- What do you know about Higham or Fellowes, the organization that commissioned the report? Google them now on your computer.

- Does what you discovered about them change your impression regarding the soundness of the report? Why or why not?

- Consider the report’s construction.

- On first glance, does the document follow the conventions for formal reports outlined in the “Reading Actively” chapter of this textbook?

- If so, how? If not, how does it deviate from the conventions, what effect does the deviation have on you as a reader, and what might be the reason for the deviation?

- Perform a close reading of the text.

- Read the report in full. Annotate as you go by highlighting keywords, phrases, and sentences and by underlining or noting down unfamiliar terms, questions, and thoughts regarding the reading.

- After reading, try to define the unknown terms you identified.

- After reading, try to answer your questions. You may need to review the essential details of the text again to do this.

- Determine the report’s purpose or thesis.

- Determine the report’s target audience.

- Identify the main idea of the section entitled “Findings.”

- Identify the main idea of the section entitled “Danger Zones.”

- Identify the main idea of the section entitled “Our Offices.”

- Identify the main idea of the section entitled “Physical Impact.”

- Summarize the text using your notes.

- Concentrate on the report’s purpose/thesis and main ideas or themes when summarizing, and omit detail

- Put the report away when summarizing it to avoid copying its language and sentence structures

- Read the report in full. Annotate as you go by highlighting keywords, phrases, and sentences and by underlining or noting down unfamiliar terms, questions, and thoughts regarding the reading.

- Perform a critical reading of the text.

- Identify how the author contextualizes the report for readers by looking for associations between its content and readers’ experiences.

- Consider your own reactions to the reading.

- What, if anything, about the reading is unclear? Why is it unclear?

- Are the author’s points logical? Do they make sense?

- Does the text deliver on the promises it made in its title and introduction?

- Do you find the author’s writing style persuasive? Why or why not?

- What ideas do you find most thought-provoking?

- What points do you want to investigate further?

- How does the reading compare with other texts on the same topic?

- Identify the evidence used to support the report’s main ideas. Evidence may be presented in the form of facts, quotations, paraphrases, summaries, and visuals.

- Is each of the author’s viewpoints (claims) supported with evidence?

- Is the evidence comprehensible?

- Does the evidence sufficiently support the claim?

- Is the evidence relevant to the claim?

- Is the evidence logically tied to the claim?

- Given the purpose of the piece and its audience, is the evidence from suitable sources?

- Is the evidence research-based (empirical), factual, or grounded in hearsay or casual observation (anecdotal), or does the author rely heavily on a reader’s emotional reactions to communicate the force of his viewpoints?

- Is the evidence credible?

- Can you easily associate citations with their references and sources?

- Identify the connection of reasons to viewpoints. The report author may state reasons outright—look for uses of seeing as, because, since, given that, and the like—or imply them.

- Determine whether the author considers alternative points of view.

- Does the author address counter-claims?

- Does the author address counter-reasons?

- Does the author address counter-evidence?

- Does the author respond reasonably to other viewpoints or simply dismiss them?

- Consider the design of the report relative to its genre.

- What impression does the design give you?

- How does the design contribute (or not) to your understanding of the report?

- Develop a thesis based on the results of your analysis and evaluation of the report.

- Does your thesis articulate the theme of your paper and express your viewpoint?

- Is your thesis an arguable statement rather than a statement of fact?

- Can the argument conveyed in your thesis be supported with claims, reasons, and evidence?

Homework: Compose a Critical Review Essay

Draw upon what you did in Activity B to write an essay that critiques “The Work Colleague of the Future: A Report on the Long-Term Health of Office Workers” (Higham, 2019). This assignment asks you to closely examine the argument presented in the formal report (analyze it) and explain to readers how effective the argument is (evaluate it). Remember that a critical review makes an argument: you will need to support your claims about the report with reasons and evidence and cite and reference all outside sources of information used. Follow the guidelines presented in this chapter when writing your paper; in addition, consult the “Writing Essays” chapter of this textbook for essay formatting guidance and the “Writing to Persuade” chapter for argumentation information. Lastly, use the points you identified in activity A to revise your work.

References

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020a). Evaluating an author’s intent. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/EvaluatingAuthorsIntent2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020b). How to make a concept map. License: CC-BY 4.0 https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/HowToMakeConceptMap2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020c). How to preview a text. License: CC-BY 4.0 https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/10/Previewing2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020d). How to use questioning to improve reading comprehension. License: CC-BY 4.0 https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/Questioning2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020e). Outlining. License: CC-BY 4.0 https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/03/HowToMakeAnOutline2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020f). Sample rhetorical analysis. License: CC-BY 4.0 https://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/argument-analysis/argument-analysis-sample-rhetorical-analysis/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020g). Tips on academic voice. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/finding-your-voice/finding-your-voice-tips-on-academic-voice/

Fellowes Brands. (2019, October 23). Meet Emma – your work colleague of the future [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fL5SuzGkUPw

Grosz, B.J. (2019). The AI revolution needs expertise in people, publics and societies. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.97b95546

Higham, W. (2019). The work colleague of the future: A report on the long-term health of office workers. Fellowes. https://assets.fellowes.com/skins/fellowes/responsive/gb/en/resources/work-colleague-of-the-future/download/WCOF_Report_EU.pdf

Hume Center for Writing and Speaking, Stanford University. (n.d.). Top twenty errors in undergraduate writing. https://undergrad.stanford.edu/tutoring-support/hume-center/resources/student-resources/grammar-resources-writers/top-twenty-errors-undergraduate-writing

McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph. (n.d.). We need to talk: Tips for participating in class discussions. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://learningcommons.lib.uoguelph.ca/item/we-need-talk-tips-participating-class-discussions

McNamee, K. (2019). Tone. Colorado School of Mines Writing Center. License: CC-BY-NC 4.0. https://www.mines.edu/otcc/wp-content/uploads/sites/303/2019/12/otcctonelesson.pdf

Roux, S., Ravaei, K., & Harper, T. (2020). Quick tips for contacting instructors over email, quick tips for meeting instructors in-person. WI+RE: Writing Instruction + Research Education. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0. https://uclalibrary.github.io/research-tips/assets/handouts/contacting-faculty-combined.pdf

Student Academic Success Services, Queen’s University. (2018). Writing a critical review. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 2.5. https://sass.queensu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Critical-Review.pdf

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Citing a source more than once. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/citing-source-more-once