Working with Others

Stacey Corbitt

Chapter Overview

In her 2009 book The Collaborative Habit: Life Lessons for Working Together, iconic American dancer and choreographer, Twyla Tharp, wrote

We’ve long forgotten how collaboration became a natural instinct. For most of us, in the dailiness of family life, collaboration is a learned habit. It’s a welcome balance to the ego’s incessant hunger for self-gratification. It’s a recognition that there’s more to life — more opportunity, more knowledge, more danger — than we can master alone. It’s the building block of community. And because it’s a balance to our self-absorption, it’s a powerful tool for socialization and tolerance (as cited in Anderson, Castillo, and Patsch, 2020, p. 17).

Anderson, et. al., referenced Tharp’s thoughts about working with others in their recent case study of a multi-disciplinary writing project in which the rich experience of collaboration is a major focus (2020, p. 17). This chapter aims to explore both the challenges and rewards of group work in college, paying specific attention to collaborative writing.

Why is collaboration employed in technical writing courses?

Students whose academic interests lie in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields may be preparing to conduct research that necessarily relies on cooperative effort. Typically, college and workplace scenarios alike involve parties whose educational and professional backgrounds vary significantly, thus presenting difficulties when interdisciplinary communication is required. Exercises in communicating across those various backgrounds, education levels, and objectives can be practiced within the security and controlled environment of technical writing classrooms and laboratories. Writing faculty might support hands-on group work assignments because they offer valuable practice for developing communication skills for use in project planning, reporting, and conflict resolution.

Preparation is key

The following discussion and activities, adapted from Rebecca Ingalls’s essay Writing “Eyeball to Eyeball”: Building a Successful Collaboration (2011), offer a realistic and thoughtful approach to setting up group writing projects for success. “Once we know why we see collaboration in certain ways …,” Ingalls wrote, “we can begin to create the kind of common ground that collaboration asks for” (p. 125). Read the following excerpts from the “Getting Started” section of the essay and respond to the writing prompts presented: your instructor may provide additional direction for discussion with classmates.

Your Experiences Matter

Take some time to think through some of the collaborative work you’ve done in the past. Without worrying about mechanics or organization—spend fifteen minutes just writing about one or two experiences you’ve had. After you’ve spent some time writing, go back and re-read your freewrite, paying careful attention to the emotions you read in your words. Do you see inspiration? Anxiety? Pride? Frustration? Confidence? Confusion? What were the sources of these emotions in your experience? How do they shape the ways in which you view collaboration today? (Ingalls, p. 125)

Now, spend some time thinking about how those collaborations were set up. Specifically,

What was the purpose of the collaboration?

How was the group selected?

How did you make creative and strategic decisions?

How did you divide labor?

If there were tensions, how did you resolve them?

How did you maintain quality and integrity?

In what ways did you offer praise to one another?

How did you decide when the project was complete?

The purpose of the preceding exercise is to engage a writer’s critical thinking skills to better understand past experience and how it informs attitudes toward collaborative writing projects (Ingalls, p. 126). Ask yourself questions like those that follow and be prepared to discuss your discoveries with your work group or classmates:

- What role did I play in that collaboration?

- More broadly, what role(s) do I tend to take in collaborative work? Why?

- How do I measure motivation and expectations of my group members?

- How do I measure fairness in dividing tasks?

- How do I measure success?

- How do I find the words to speak up when I want to challenge the group?

Record your preparation and/or discussion notes here:

Armed with an understanding of how past experience shapes your attitudes about and expectations for group work, consider Rebecca Ingalls’ recommended next steps in pursuing a successful collaborative writing experience (excerpted from pp. 128-130).

Establishing a Group Contract

Once you’ve established your group, there is an important step to take before you dive into the work, and in many ways it acts as your first collaborative writing activity: the group contract. This contract serves as a kind of group constitution: it lays out the collective goals and ground rules that will adhere group members to a core ethos for productive, healthy, creative work. It also gives you a map of where to begin and how to proceed as you divide the labor of the project. In composing your contract, consider the following issues.

Understanding the project at hand

From the get-go, group members should have a clear, shared understanding of what is expected. Engage in a discussion in which you articulate to one another the goals of the project: what is the composition supposed to accomplish? What should it teach you as the authors? Discuss the parameters of the project: form, length, design, voice, research expectations, [and] creative possibilities.

Communication practices

Spend a few minutes discussing together what “good communication” looks like. This conversation may offer you a valuable opportunity to share some experiences and get to know one another better. Once you have outlined your standards for communication, establish ground rules for communication so that your group fosters sharp listening and makes space for a diversity of ideas and perspectives. Will you meet regularly in person, or will you rely on electronic means like email, chatting, a wiki, online collaborative software like Google Docs, or Facebook? If you use email, will you regularly include all group members on all emails to keep everyone in the loop? How will you vote on an idea? What if everyone agrees on a concept except one person? What if tensions arise? Will you deal with them one-on-one? In front of the whole group? Will you involve your teacher? When and why?

Meeting deadlines

Discuss your group members’ various schedules, and establish a deadline for each component of the project. Decide together how you will ensure that group members adhere to deadlines, and how you will communicate with and support one another in achieving these deadlines.

Ethics

Discuss academic integrity and be sure that each group member commits to ethical research and the critical evaluation of sources. Each member should commit to checking over the final product to be sure that sources are appropriately documented. Rely on open, clear communication throughout the process of research and documentation so that you achieve accuracy and a shared understanding of how the text was composed, fact-checked, and edited.

Standards

Discuss together what “quality” and “success” mean to each of you: is it an A? Is it a project that takes risks? Is it consensus? Is it a collaborative process that is enjoyable? Is it the making of friends in a working group? How will you know when your product has reached your desired quality and is ready to be submitted?

As you can see, this contract is not to be taken lightly: time and effort spent on a reliable contract are likely to save time and energy later. The contract acts as the spine of a group that is sensitive to differences of experience and opinion, and that aims to contribute to the intellectual growth of each of its members. While the contract should be unified by the time you’re done with it, allow space for group members to disagree about what is important—working with this disagreement will be good practice for you when it comes to composing the project itself. When it’s completed, be sure that each group member receives a copy of the contract. You should also give a copy to your teacher so that he/she has access in the event that you want your teacher to be involved in conflict resolution. Keep in mind, too, that the best contracts are used to define your responsibilities and enhance communication, not to hold over one another—your contract is a thoughtfully composed articulation of your goals, not a policing tool.

Discuss Ingalls’ recommendations with your class or the members of your work group. How might you consider employing some or all of her suggestions as you proceed into a collaborative writing assignment? What difficulties do you and your peers anticipate that Ms. Ingalls did not address? Work at being frank but respectful of each other as you discuss your expected challenges and list those concerns below. Be prepared to report on your group’s discussion with the class as you prepare to complete the following activity.

Activity: Is learning to collaborate worth the discomfort?

Read the following text, which is adapted from Collaborative Design and Creative Expression with Arduino Microcontrollers: Cultivating a Culture of Collaboration (2017). Discuss the reading with your classmates as directed by your instructor. Be prepared to discuss the reading.

Cultivating a Culture of Collaboration

In this section, Kyle Keane and Andrew Ringler discuss the centrality of teamwork in the workshop. They also share two strategies fostering a culture of collaboration.

The Importance of Teamwork

We believe collaborating with other people is an enjoyable part of life. It’s also critical. As technology becomes more complicated, it’s growing increasingly less feasible to do

any significant project alone. An important aspect of the Arduino workshop is helping participants learn comfortable ways to form teams and to function productively within them. In fact, in naming the workshop, “Collaborative Design with Arduino Microcontrollers,” we intentionally put the word “collaborative” first in the title; participants use Arduinos to program microcontrollers, but engaging in teamwork is really the focus of the workshop experience.

Setting Expectations

So how do we cultivate a culture of collaboration? On the first day of the workshop, we talk explicitly about how the point of being together in this shared space is for participants to find things that excite them, for them to share this excitement with others, and to feel vulnerable. In other words, we’re here for social learning and social reinforcement. We tell students, “This workshop is voluntary. You can choose to be here or not, and you can leave at any point. So, if you stay here, stay here for a purpose. Stay here to interact with other people.” Having this conversations helps us establish the expectation that collaboration will be a norm in the workshop.

Modeling Vulnerability

Modeling social vulnerability also helps us foster a collaborative learning environment. And this can feel really embarrassing! After all, modeling vulnerability in front of a classroom of undergraduates and graduate students is not something we typically do when we’re deriving at a blackboard. But we should!

So we make a point to do it in the workshop. Recently, participants were giving presentations in the workshop. I (Kyle) stood up in the front of the classroom and role-played with the participants. At the beginning of my mock-presentation, I said, “I’m sharing my work with you. What is your response going to be? I need you to ask questions that are supportive, that show that you’re interested.”

I also spoke about the emotions and their physical counterparts, like sweaty palms, that I was experiencing. I encouraged them to share their work with others despite feeling vulnerable: “You’re going to feel nervous. You only had two weeks to work on your projects and you didn’t come to this workshop with professional skills; this is not a refined presentation. Don’t be embarrassed. Just feel those feelings and share your work.”

Modeling vulnerability is not a very common post-secondary teaching strategy, but I think it’s an important thing to do when building team dynamics, because, let’s face it, opening yourself up to critique is terrifying. And there’s no point at which it stops being terrifying. So, as instructors, we try to face our own fears about doing it. We stand in the front of the classroom and talk about how it feels to be vulnerable. We’re weirdly explicit about it, but we find it extremely effective.

Drawing on Improvisational Comedy

I use improv warm up exercises (games performers play to get ready for a show) to help participants explore how verbal and nonverbal communication impact their collaborative relationships in the workshop. — Andrew Ringler

I (Andrew) tend to draw heavily on my experience with improvisational comedy, or improv, to lay the foundation for the social interactions that make teamwork possible and enjoyable. One thing that’s really interesting about improv is that there’s no script, so the only focus is you and the other person on stage. Together, you have an impromptu conversation, responding to each other, without having any idea what your partner will bring next to the conversation. It’s about working in relationship with one another. I use improv warm up exercises (games performers play to get ready for a show) to help participants explore how verbal and nonverbal communication impact their collaborative relationships in the workshop.

One of the improv exercises I do is called Red Ball. Participants pass an imaginary red ball, and, over time, the game gets complicated, because we introduce more imaginary balls that have similar sounding names, like “yellow ball,” “bouncy ball,” and maybe “bread bowl” or “Red Bull.” There’s an action associated with every ball name, such that when participants toss a “Red Bull,” they have to act out opening a can of soda. We quickly introduce balls as others are being passed around, and it creates chaos.

At the end of the exercise, I ask, “Who has the red ball? Who has the yellow ball? Who has the Red Bull?” Sometimes two or more people think they have particular balls. Or a ball goes missing! This leads to conversations about the importance of agreement in communication. Participants have to think about who they passed a ball to, and if that person agreed to receive it. In other words, did that person even know someone was passing them a particular ball? We also talk about what happens when there’s no one to receive a ball, because everyone’s looking in different directions. In other words, the exercise allows us to have conversations about the communication issues participants will encounter in their collaborative design process. It’s also a fun way to get participants comfortable making mistakes—which reinforces the idea that being vulnerable in this setting is not only okay, but the norm.

Think about your instructors, past and present. Based on your understanding of Kyle Keane’s discussion of his approach to modeling vulnerability, can you recall an instructor you think has attempted to relate to you and other students by allowing their own insecurities to be seen? Describe that experience, including the way(s) it impacted you.

Getting the work done: approaches

Whether group writing projects involve teams of two or ten partners from the same academic background or different ones, setting and following a deliberate plan is crucial to accomplishing the goals of those projects. Part of that deliberate plan might be developing the collaboration contract as discussed in the previous section. Beyond making a commitment to collaborate mindfully throughout the project, the work group must begin and complete the document(s) in order to claim success. While as a student you may be writing in a collaboration with defined parameters and other requirements, consider the “Approaches to Collaborative Writing” as presented by Kait McNamee of the Colorado School of Mines Writing Center (2019).

Approaches to Collaborative Writing

Single Author Writing

Sequential Writing

Reciprocal Writing

Parallel Writing

Skill-based Division Writing

Working with a partner or your assigned work group, discuss the various approaches listed. Which of these styles of collaborative writing have you and your partners experienced? How did those approaches work? Discuss which approach(es) would not be appropriate for your current writing assignment(s) and why. Be prepared to explain your responses in class.

Getting the work done: project management

The contract is ratified, the topic is chosen, the approach is determined: it’s time to get results. Managing a collaborative writing project is a process that may be largely prescribed by the group work agreement in that decisions have already been made about a variety of matters. For example, the group members’ leadership roles, the milestones and meeting schedules may all be defined in the group contract: the project management, then, according to Rebecca Ingalls (2011, pp. 132-133), begins with creating a plan.

Together, divide the project into logical stages of development, taking into consideration what the composition will need in terms of its research, analysis, organizational sections, graphics, fact-checking, editing, and drafting. Also consider the responsibilities necessary for each of these stages.

Next, divide the labor mindfully and fairly by discussing who will take on each responsibility. Think back on your experience and tendencies with collaboration. Is there an opportunity to do more listening, leading, negotiating, or questioning than you have in the past? Are there unique talents that individuals can bring to the project’s various elements? Is one of you interested in design or illustration, for instance? Is another interested in multimedia approaches to presentation? You may elect a “divide and conquer” approach, but consider, too, that some sections of the project may require a sub-set of group members, and that other sections will need everyone’s input (like research, editing, checking for documentation accuracy, decisions on design). In combining your individual skills with common goals, you’re likely to find that the work you’re doing is much greater than the sum of its parts. While individual group members’ specific skills will be spotlighted in their own ways, this plan for the management of the project should also reveal that every stage of the process gets input from each member.

Activity: What if we have trouble?

- Working with your team in class or as directed by your instructor, discuss conflicts the group members have experienced in past collaboration experiences. As you discuss, develop a list of “What If” questions that represent issues that might occur within your own team on the current project.

- As you review and discuss the various “What Ifs” you have identified, return to your collaboration contract. What is the conflict resolution protocol you agreed upon? If there is no clear or adequate method for addressing unexpected disagreements or work stoppages, how might the team navigate those issues to keep progress on schedule?

Check the vital signs and make adjustments

Along with the “What If?” questions, successful teams recognize the dynamic nature of projects and group work, and collaborators make efforts to check in with each other and their schedule.

Review the following excerpt from Rebecca Ingalls’s Writing “Eyeball to Eyeball” (2011, p. 135) and complete the activity that follows it.

While you’ve worked hard to compose your group contract, it can be difficult to keep the elements of the contract in the forefront of your mind when you and your group members immerse yourselves in the project. Instead of moving the contract to the back burner, be sure to return to it once or twice throughout the project. In reflecting on collaborative work, one student in my class remarked, “People’s roles in the project, responsibilities, work done, that can all be adjusted, but when it is time to submit it you have no room to improvise.” The “adjustments” that this student refers to can happen when you and your group touch base with the goals you set from the beginning. You might also find that it’s useful to meet briefly as a group in a more informal setting, like a coffee shop, so that you can take a refreshing look at the status of the project so far. Specifically, you might examine the following aspects of your collaboration:

- Revisit your goals. Is your composition heading in the right direction?

- Rate the overall effectiveness of communication. Call attention to any points of conflict and how you managed them.

- Discuss the workload of tasks completed thus far. Has it been fair?

- Measure the quality of the work you think the group is doing thus far.

- Remind yourselves of past and future deadlines. Do they need to be revised?

- Raise any individual concerns you may have.

If this extra step seems like more work, consider the possibility that as you push forward with the project, your goals may change and you may need to revise your contract. This step acts as a process of checks and balances that helps you to confirm your larger goal of creating a healthy, productive, enjoyable collaboration.

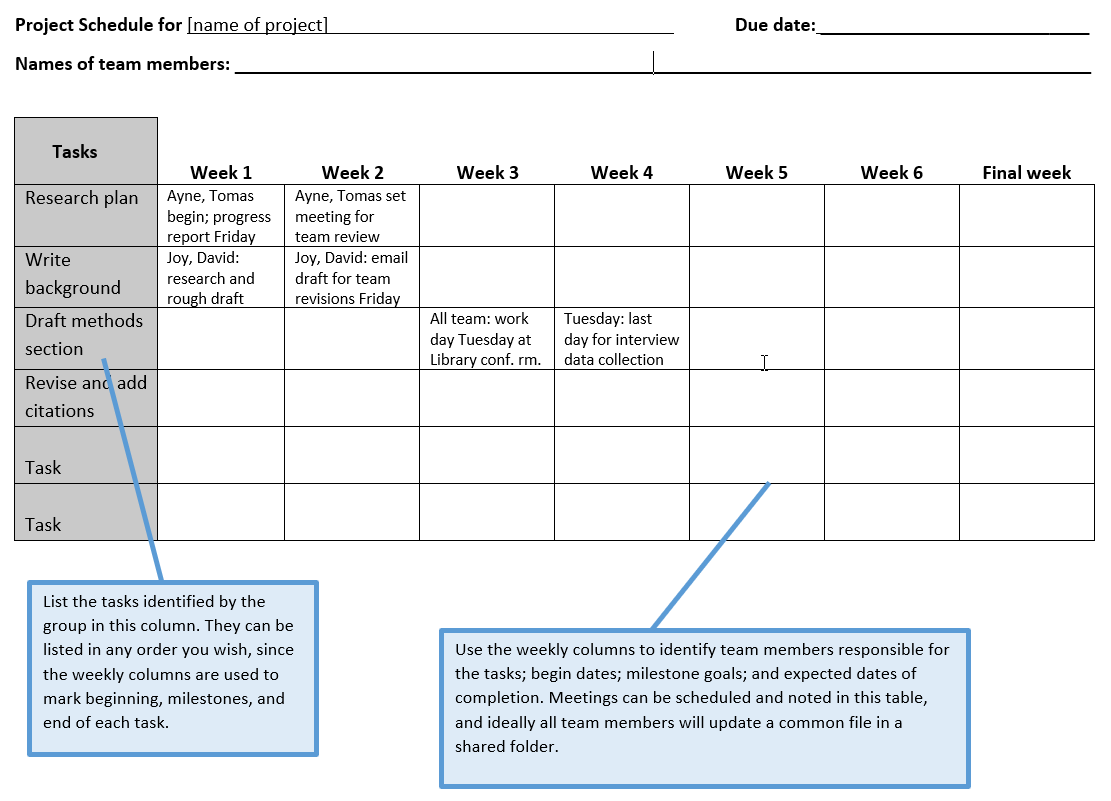

Activity: Create a living project schedule

Using the assignment specifications provided by your instructor, draft a preliminary work schedule for your collaborative writing project. The worksheet provided on the next page is a simple representation of a weekly work schedule with identified milestones; however, your team may want to use a different format for scheduling tasks. Some collaborative writing teams prefer, for example, to build their schedule using a Gantt charting form. A Gantt chart provides a detailed visual representation of the relationships between and among tasks, making interdependent or subordinate processes easier to identify. Whatever format you and your team members choose, remember the purpose is to create a visual representation of your project that is accessible and easy to review, share, and revise as needed.

Review and reflection

As discussed in detail in the chapter of this textbook entitled Reflecting on Performance, much can be learned from thoughtful consideration of the processes followed in completing a task. Just as preparation is a key to launching a collaborative writing project, completing a review and assessment of the process and the outcomes helps to ensure your experience benefits your efforts in the next collaboration. Rebecca Ingalls offers some “guiding questions” in her essay (p. 137) for the reflection process.

- Was your project a success? If so, why? If not, why?

- What were some of the most poignant lessons you learned about yourself?

- What surprised you about this collaboration?

- What might you have done differently?

- In what ways did this collaboration change or maintain your perceptions of collaborative work?

- How would you instruct someone else in the process of collaboration?

Once you’ve done your own reflecting, take your observations back to your group, and discuss together what you’ve concluded about the process. Not only does this final step bring some healthy closure to the project, but it also opens up opportunities for resolution of lingering conflict, mutual recognition of your accomplishments, and, for those of you who’ve got an especially good thing going with your work, a conversation about possibly taking your project beyond the classroom.

Chapter conclusion

Collaborative writing benefits everyone involved every time it is used. It offers writers great opportunities to learn about strengths and develop interpersonal communication skills while providing rich opportunities to give and receive feedback from peers. Group work exposes all team members to new ideas and innovative approaches to all aspects of work from planning to project completion and reflection. Collaboration on documents has a built-in benefit of many hours of critical reading and thoughtful writing and editing. Finally, writers benefit from the processes of learning and participating in negotiations with team members by taking responsibility for shortcomings as well as successes realized by the writing team.

Homework

- Work as a group to write a memo to your instructor detailing your group’s work plan for managing and completing your collaborative writing project, including a specific method for resolving conflicts that arise within the group. Provide helpful illustration in the form of the graphical representation of your project schedule, either in a table format as provided in this chapter, a Gantt chart, or another graphic developed by your team.

- Following your group’s presentation or other submission of your collaborative writing project, write a business letter to your instructor detailing a post-process reflection on your group’s experience and performance. Use the guiding questions provided above to develop the reflection report.

References

Anderson, S., Castillo, H., & Patsch, K. (2020). Collaborating for the coast in performing arts, environmental science and resource management, and English. IMPACT: The Journal of the Center for Interdisciplinary Teaching and Learning. 9(2), 17-34. License: CC-BY-4.0.

Ingalls, R. Writing “eyeball to eyeball”: building a successful collaboration. (2011). In C. Lowe & P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing: Volume 2 (pp. 122-140). Anderson, South Carolina: Parlor Press. License: CC-BY-NC-ND-3.0.

Keane, K., Ringler, A., Vrablic, M., & Gandhi, A. (2017). Collaborative design and creative expression with Arduino microcontrollers. January IAP 2017. RES.3-002. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare. https://ocw.mit.edu. License: CC BY-NC-SA.

McNamee, K. (2019). Collaborative writing handout. Colorado School of Mines Writing Center. License: CC-BY-NC-4.0. https://otcc.mines.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/303/2019/12/otcccollaborativewritinglesson.pdf