Writing to Persuade

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

This chapter discusses the fundamentals of argumentation by exploring what arguments are, what elements comprise them, and what factors bolster or weaken the strength of arguments in an effort to help you learn how to compose them. Argumentation is a pervasive feature of writing: for example, authors employ persuasive tactics to encourage readers to adopt certain perspectives, to consider the importance of information, to support or fund projects, to read beyond the first lines of a document, and, more generally, to consider the competent construction of a text and its fluid means of communicating information. Although some of these circumstances call for a nuanced approach to persuasion, this chapter addresses explicit argumentation in documents in an effort to lead into the chapter’s deliverable, a researched argument essay. This type of essay relies on research-based evidence to build a case for something that is debatable.

What are arguments?

By definition, arguments articulate viewpoints, support the views with evidence, and provide reasons to link the elements together. For arguments to be arguments, the views espoused have to be debatable, meaning that different people can take different positions on them. When composing an argumentative piece, the objective is to persuade readers that your viewpoint is sound through the logical and coherent delivery of quality information.

What are the building blocks of arguments?

An argument is composed of three key elements: claims, evidence, and reasons. A claim communicates a standpoint, a particular stance on something. Taking this definition into account, some claims cannot be argued. Facts, for example, cannot be argued because they are indisputable, meaning they are true in all instances. Points of view that cannot be supported with research-based evidence also cannot be argued, at least not in academia or the workplace. Evidence is information used to support claims so that readers can make determinations regarding their legitimacy. Evidence can take a wide variety of forms, such as quotations, paraphrases, summaries, visuals, numerical data, and facts, although readers should readily understand the connection between claims and evidence, perceive that the evidence sufficiently reinforces the claims, and regard the evidence as credible. Reasons connect claims and evidence. In plain terms, a reason is a because statement, a rationale for a claim that leads into the evidence that supports the claim, although a reason may sometimes be implied by a writer rather than stated outright. Sound arguments contain all three elements described here: claims, evidence, and reasons.

Strong arguments also include coverage of alternate points of view—in other words, counterarguments—and their accompanying claims, evidence, and reasons. By incorporating these elements, writers demonstrate that they

- Recognize the multifaceted nature of issues.

- Can be reasonable by considering different viewpoints.

- Have been thorough when investigating topics.

Writers have choices when deciding how to acknowledge counterarguments. They can concede that the arguments are valid, at least in part, to demonstrate a fair-minded approach. Indeed, they might use certain phrasing to indicate this intention, as the following examples illustrate.

- While it is true that ___, I argue ___ because ___.

- ___ makes a legitimate point when claiming that ___; however, he/she seems to overlook ___, which is a key concern for ___.

- Although I concede the legitimacy of ___, I still maintain that ___ because ___.

- Though ___ is no doubt an authority on this issue, the evidence points to ___.

Alternatively, writers may refute the validity of counterarguments by first explaining them—touching upon their claims, evidence, and reasons—before seguing into a discussion of their own arguments. Writers may signal this intention to readers by using the following phrases or similar.

- ___ makes the point ___, but another way to view this topic is ___.

- This paper however argues ___.

- ___ claims that ___ but offers little research-based evidence to support that viewpoint. I instead contend that ___, using ___ as evidence to support my view.

- ___ challenges the view that ___ because ___.

Whether writers concede or refute the legitimacy of counterarguments, they should maintain a respectful tone and treat opposing sides fairly rather than belittling or oversimplifying them. Doing so will help to establish credibility in readers’ eyes, contributing to the persuasiveness of the writers’ documents.

What are the different types of claims in arguments?

If we acknowledge that a claim communicates a standpoint, it stands to reason that claims can be more or less strong. A spectrum of strong and less strong language can be used both when presenting one’s own claims and when reporting others’ claims to indicate, for example, degrees of likelihood, rates of occurrence, or measures of extent.

- Degrees of likelihood: certainly → probably → likely → possibly → doubtfully

- Rates of occurrence: always → usually → often → rarely → never

- Measures of extent: all → most → many → few → none

When writers feel certain about claims, they may use strong (unqualified) language to articulate them in a straightforward manner, as in the following example.

Students who spend two hours on homework for every one hour of class time are more successful in college.

On the other hand, if writers wish to acknowledge that claims might not be true in every situation, they can use qualified language (also referred to as hedging) to moderate the force of those claims, as in the following example.

Students who spend two hours on homework for every one hour of class time tend to be more successful in college.

Qualified language does not necessarily point to a flawed claim or argument; instead, it demonstrates a careful approach to argument construction, one that takes target readers’ anticipated reactions to a text into account. However, misrepresenting reality by making exceptionally weak claims implies an attempt to mislead readers that can damage the persuasiveness of an otherwise sound argument.

In addition to the points about qualifying language already mentioned, also be aware that different verbs convey different levels of certainty when paired with claims. Table 1, adapted from Lingard (2020, p. 108), presents examples of verbs and the degrees of inevitability they express.

Table 1. A variety of verbs and their associated levels of certainty

| Degrees of Certitude | Verbs |

|---|---|

| Strong | know, understand, argue, affirm, stress, debate, emphasize, maintain, declare, stipulate, warn, conclude, clarify, identify, insist |

| Moderate | comment, explain, indicate, note, observe, state, describe, identify, find, suggest, indicate, say |

| Weak | speculate, wonder, believe, note, offer, view, suspect, consider, propose |

To demonstrate the idea that verbs communicate various levels of strength when paired with claims, read the following journal article title (from Letessier et al., 2019).

“Remote Reefs and Seamounts are the Last Refuges for Marine Predators across the Indo-Pacific”

Do the writers make a strong or tentative claim? How do you know?

Next read a sentence from the “Concluding Remarks” section of the same article. Although you may not understand all the specialized terminology used in the extract, think about the level of certitude associated with the verbs in the sentence.

“We propose that identifying these in the pelagic realm, specifically outside national jurisdictions in the high sea, should be a research priority.”

Do the writers make a strong or tentative claim? How do you know?

Now read this thesis from a student’s argumentative essay (Jackson, 2014, p. 1, as cited in Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020e, “Sample Toulmin Argument”).

“Just because child beauty pageants are socially acceptable does not mean they should

- Our culture needs to eliminate child beauty pageants, at least in their current form.”

Does the writer make a strong argument, a tentative argument, or combine levels of certitude? How do you know?

When writing an argumentative piece, consider your audience carefully, and try to anticipate how much readers know about your topic, what kind of resistance they might put up to your position or the information you present, and what you can reasonably do to convince them otherwise through your use of language.

How is a researched argument essay organized?

As this chapter’s introductory paragraph indicates, arguments are a ubiquitous feature of written communication. An employee might send his supervisor an email message, for instance, to ask for time off and present evidence and reasons to support his case, while a student in search of college funding might complete a scholarship application and bolster the strength of her submission with evidence and reasons. A researched argument essay similarly makes it point with claims, evidence, and reasons.

Like other types of essays, a researched argument is composed of an introduction, body, and conclusion section, plus a reference page that provides the full bibliographic details for citations listed in text. An introduction presents context-setting or background information, reveals the document’s central argument, and outlines the paper’s structure; the body paragraphs expound on the essay’s central argument until it is fully developed; and the conclusion emphasizes the document’s central argument and reiterates key takeaways.

How is an essay’s central argument communicated?

A writer uses a thesis statement, a sentence or two placed at or near the end of an introduction section, to communicate an essay’s central argument. The thesis expresses the author’s informed opinion on a topic and controls the development of the rest of the paper by defining its focus and scope. Establishing an initial research question is a useful first step in composing a thesis statement since a research question delimits the direction of a project. A research question, in other words, guides the course of research associated with a project, helping a writer explore a subject in order to formulate an informed opinion about it. A thesis statement, in turn, answers a research question in sentence form. Read the following example, adapted from McKeever (n.d.-c, “Formulate a Thesis & Start to Organize”), to see the connection between a research question and a thesis statement.

- Research question:

- What is so bad about cheating in college?

- Points discovered through research:

- It condones deceit.

- It impedes the learning process.

- It creates residual effects in other aspects of life.

- Working thesis statement:

- Cheating in college impedes the learning process, leaving students ill-prepared for the complexities of the workplace; worse still, it makes them callous about cheating in government and business.

A working thesis statement can usefully guide the development of an argument essay, but be prepared to refine it as a paper takes shape.

While a research question can help facilitate the formation of a thesis statement by encouraging investigation of a topic, a writer may also need to ask probing questions of the information discovered through research to flesh out the direction of a paper. Your initial set of questions will likely concentrate on the quality of evidence you gather through research since evidence is one of the building blocks of arguments. Although other chapters of this textbook address source evaluation in some depth, the handout in Figure 1, adapted from Carey (2020, p. 2), offers a reminder of questions to ask when evaluating source quality and when considering the relationship of evidentiary information to your paper’s purpose and context. Be discerning in your choice of sources to boost the persuasiveness of a paper.

Figure 1. Questions for evaluating source quality

As you identify evidentiary sources, also think carefully about what they contribute to your paper. You may need to ask further probing questions of the sources in the process of formulating a thesis statement to discover how they are similar and different, how they intersect with your own ideas, and how this combination can help inspire the creation of new ideas through synthesis. Figure 2, adapted from McKeever (n.d.-a, p. 2), lists a number of inquiries to facilitate this stage of questioning.

Figure 2. Questions for developing an argument

Asking such questions of source information may help sharpen the focus of a thesis statement.

When writing a thesis for an argument paper, remember that it must articulate a specific and debatable point in sentence form. The following essay thesis, taken from McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph (n.d.-b, “Argument”), exemplifies how an unambiguous thesis can help guide the development of a paper.

“Volunteer tourism in southeast Asia [topic] should be more strictly regulated [position] to prevent economic, social, and cultural exploitation [reasons].”

Readers will almost certainly be able to anticipate how the rest of the essay will unfold after reading this sentence in the introduction. Use the prompts in Figure 3 (adapted from McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph, n.d.-a) to help craft a specific and debatable thesis for an argument paper.

Figure 3. Prompts for creating specific and arguable thesis statements

Developing a sound thesis statement takes some work, but the effort will contribute to the logical development of your paper and your readers’ ability to follow it.

How is an essay’s central argument developed?

A writer develops an essay’s central argument in a series of body paragraphs. Each body paragraph should focus on one main point so that readers can easily follow the essay’s structure. This main point is articulated in a topic sentence, which is typically placed at the beginning of a paragraph, enabling readers to immediately identify the paragraph’s focus. Everything that follows the topic sentence—for instance, examples, evidence, explanations, elaborations, and illustrations—should relate to the paragraph theme introduced in the topic sentence to give the paragraph unity. A writer connects the individual parts of the paragraph by using various devices, such as purposeful repetition, transitions, synonyms, antonyms, pronouns, and punctuation marks, to establish a coherent flow. Figure 4, adapted from the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d., p. 1), likens the connections among an argument’s components to a tree trunk and its branches.

Building Strong Body Paragraphs

A strong body paragraph explains, proves, and/or supports your argument/claim/thesis statement. It may be useful to think of your paper as a tree: the trunk represents the whole paper, which is designed to prove your main argument, while the branches signify individual body paragraphs that develop your supporting claims or arguments. These components must work together to effectively develop your primary idea or overall claim. Ultimately, each body paragraph should be unified, coherent, and fully-developed.

An effective body paragraph will usually accomplish the following:

1. Express a Claim/Point/Argument

Identify the main idea of your paragraph and its relevance to your thesis or argument.

Elaborate on the topic if it requires further clarification, context, or specificity.

2. Provide Evidence in Context

Choose your evidence source and summarize the context.

Incorporate appropriate evidence to support your claim. The evidence may consist of quotations, examples, statistics, facts, etc.

3. Analyze Evidence and Link to Larger Argument

Explain what the evidence means and how it connects to the argument in your paragraph or thesis statement.

Focus on synthesis (connecting themes and traits that you observe in your evidence) and analysis (interpreting the evidence and its significance). This kind of work establishes credibility by showing that you understand the evidence and its importance in your argument.

Sample paragraph (separated by claim, evidence, and analysis)

- Claim: While there is little doubt that extracurricular opportunities at UW are a positive and critical component of students’ overall development, providing students with time management skills is equally important.

- Evidence: One only needs to look at past alumni to see the validity of this claim. As famous alum Harry Wright states: “I sometimes overdid it with extracurricular activities when I was at U of W, missing out on valuable academic opportunities. Fortunately, I buckled down in my senior year and managed a “C” average, and things have worked out fine since” (Page 227).

- Analysis: In this example, Harry Wright is arguing that the detrimental effects of excessive extracurricular involvement can be rectified in the senior year of university. Even though Harry Wright is certainly correct when he implies that it is never too late for students to try to raise their GPA, it is probably better for students to attempt to balance academic and other activities early in their university career. Also, Wright assumes that all students can achieve what they want with a “C” average, but many students need higher GPAs in order to apply for professional school, graduate school, and entry-level jobs. Although extracurricular activities are often a positive and critical component of student life at UW, administrators should consider providing a time management education and awareness course for all incoming students. After all, not every UW graduate will be as lucky as Harry Wright. If UW students are going to succeed in business and higher education, they need to first understand the importance of time management.

Tip: students are often taught the “hamburger” method of constructing body paragraphs (where claim, evidence, and analysis are layered on top of each other in a formulaic way). However, as you develop your writing style further, you should be aware that more nuanced writing will often navigate back and forth between evidence and analysis. See academic journals in your discipline for different strategies.

Figure 4. The connection between a central argument and its essential components

As Figure 4 explains, everything in the body paragraphs of a researched argument essay should relate back to the thesis statement, which expresses the central debatable point of the piece, to give the text an overall logical structure.

You have several options for the arrangement of body paragraphs in a researched argument essay.

- Block method of organization (foregrounding the writer’s viewpoint): When using this method, discuss your claims, evidence, and reasons in early body paragraphs before discussing counterclaims, evidence, and reasons in later body paragraphs.

- Block method of organization (foregrounding the opposing viewpoint): When using this method, discuss counterclaims, evidence, and reasons in early body paragraphs before discussing your own claims, evidence, and reasons in later body paragraphs.

- Point-by-point method of organization (foregrounding the writer’s viewpoint): Discuss one claim, piece of evidence, and reason before discussing the associated counterclaim, piece of evidence, and reason, and then repeat in subsequent paragraphs until your argument is fully developed.

- Point-by-point method of organization (foregrounding the opposing viewpoint): Discuss one counterclaim, piece of evidence, and reason before discussing your associated claim, piece of evidence, and reason, and then repeat in subsequent paragraphs until your argument is fully developed.

Following these patterns of arrangement in an essay helps to ensure all the necessary components of an argument have been addressed.

To help you become familiar with how a researched argument might be organized, decide which arrangement pattern is used in the following student essay sample. How did you come to your decision? The sample is adapted from St. Martin (2020, as cited in Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020d, “Sample Rogerian Argument”) and follows APA seventh edition style guidelines.

Sample Rogerian Essay

The Debate About Homeschooling

Charles St. Martin

School of Undergraduate Studies, Excelsior College

Writing 123: Writing Fundamentals

Dr. Elizabeth Smith

January 8, 2020

2

The Debate About Homeschooling

Over 20,000 Oregon students attend school at home (Hovde, 2013), and according to Martin-Chang et al. (2011),

the national number of homeschoolers was close to 1.5 million children in 2008. Hovde (2013) estimated that the

numbers account for about 2.9% of the total school-age population in the United States, a significant statistical

proportion. She noted that while homeschooling has become a fashionable choice for young urban professionals

who want the best education for their children, including many in the Pacific Northwest, the subject is still fraught

with controversies about cognitive and social development, governmental involvement, standards, and safety.

Opponents of homeschooling believe too much is often left up to parents, who can teach their kids anything they

desire and limit contact with other perspectives and environments. Homeschooling is often associated with ex

tremism, and potentially abusive situations are difficult to identify when the victims are isolated. Additionally, op

ponents fear that some parents choose homeschooling reactively out of fear or displeasure, rather than making a

thoughtful choice based on their children’s needs. Proponents of homeschooling believe homeschooled children are

healthy and advanced learners because they receive one-on-one attention and often have some degree of control

over their own learning. They believe parents can make the best choices for their children. Research and anecdotal

evidence demonstrate that these positive claims are true in safe situations but are lost in extreme cases. Ensuring

safety and educational support for all homeschooling students should be a top priority as the state works to ensure

that parents who want to still have an opportunity to homeschool their children.

Plenty of information exists to validate the concerns of the opposition to homeschooling. In many cases, parents

do have total control over the homeschooling environment. Oregon, for example, monitors homeschoolers by re

quiring children to take standardized tests in third, fifth, eighth, and tenth

3

grade (Hovde, 2013). This requirement is the only major assessment. According to Joyce (2013), many states require

even less from families who choose to homeschool: 26 states do not require any testing, and 11 do not ask for any

kind of notification from homeschooling parents. In these locations, parental discretion becomes the law in place of

any formal guidelines. Perhaps in most cases, such parental freedom benefits the children, but in others, as oppo

nents note, the children lose out.

In her article “The Homeschool Apostates,” Joyce (2013) tells the stories of several former homeschoolers whose

educational experiences were dangerous and harmful because of their parents’ fundamentalist stance. One woman

explained,

I was basically raised by someone with a mental disorder and told you have to obey her or God’s going to send

you to hell….Her anxiety disorder meant that she had to control every little thing, and homeschooling and her re

ligious beliefs gave her the justification for it. (para. 6)

In this same example, the parents also failed to take an active interest in teaching their children, choosing instead

to simply hand out schoolbooks and require their pre-teens to self-teach. Joyce argued that this type of situation is

not anomalous and cited websites such as Homeschoolers Anonymous and No Longer Quivering where hundreds

of others have shared similar accounts of their homeschooling experiences. These students are in situations that

are detrimental to their emotional, intellectual, social, and sometimes physical health, but little is done to protect

them.

Questionable outcomes are not just limited to abusive situations. Sometimes, homeschoolers struggle to achieve

on the same level as their peers despite their parents’ best intentions. According to Martin-Chang et al. (2011), chil

dren whose parents chose “unstructured” homeschooling did not achieve academically on the same level as their

peers, falling behind students who participated in structured homeschooling and traditional schooling (p. 200). In

the unstructured form of homeschooling, the

4

learning process is entirely determined by the child, whereas in “structured” forms, “the parents [view] themselves

as important contributors to their children’s education” (pp. 197–198). Structured homeschooling may still focus on a

child’s individual interests, but the parents create lesson plans or otherwise guide the child’s learning (Concordia

University, 2012). In an interview for Concordia University (2012), Martin-Chang acknowledged that the results of

the study might have been different if student achievement had been measured using a different tool—the results

were garnered from a standardized test with no connection to either the public school curriculum or homeschool

groups—or if the children had been more than 10 years old at the time of the test. Despite these qualifiers, Martin-

Chang felt the study’s initial findings were in keeping with other research that suggests parental engagement with

the child’s learning is a good indicator of academic success. In some forms of homeschooling, it appears that there

is a lack of this essential involvement.

On the other hand, homeschooled students whose parents instituted some structure scored higher on the inde

pendently implemented test than both the traditional students and the unstructured learners (Martin-Chang et al.,

2011, p. 199). This result supports earlier, although potentially flawed, research indicating the high achievements of

homeschoolers (pp. 195–196). Additionally, such findings underscore the claims of those who believe that home

schooling can have big benefits for children. Many believe that the big reason for homeschool success is parental

investment. Martin-Chang et al. (2011) hypothesized, “This advantage may be explained by several factors includ

ing smaller class sizes, more individualized instruction, or more academic time spent on core subjects such as read

ing and writing” (p. 200). The flexibility of the homeschool environment allows parents to tailor the material and

the schedule to the needs of their children, who, ideally, they know well and love tremendously. Public school

teachers cannot currently devote the same time to each child because they have full classrooms

5

and additional demands on their attention from administrators and political figures.

Clearly, both opponents and proponents of homeschooling have well-supported arguments for their positions.

Homeschooling is an option that often leads to high achievement and personal satisfaction for students. However,

some situations are unhealthy and potentially harmful to a child’s development. The solution to the homeschool

controversy is a balanced approach that upholds the benefits of homeschooling while accounting for dangers.

While, as Hovde (2013) noted, abuse can occur in any educational setting, Joyce (2013) thoroughly demonstrated

that abused homeschoolers have a harder time finding access to help, emphasizing that, in the past “homeschool

ing families had to look for help through an informal grapevine of survivors” (para. 44). Now, those survivors are

pushing for legal reforms that assess state policies for protecting homeschoolers. In order for homeschooling to re

main a safe and rewarding option for parents and students, these extreme cases need to be taken seriously.

Resources need to be readily available, and anyone found to have abused a child should be held accountable. Those

who support homeschooling should also support reforms that make homeschooling safer for everyone.

In addition, more research needs to be conducted on unstructured homeschooling, perhaps using a more holistic

measuring tool since standardized tests are known to be problematic. Parents who are deciding how to educate

their children should have access to accurate information about child development and learning. If total freedom is

not the best option for children, parents should be encouraged to seek alternative methods of homeschooling. The

bottom line is that parents have a great deal of influence on their children’s learning, whether that learning is done

in a traditional school or at home. Hovde (2013) said, “better scores should be expected when parents are so in

volved in a child’s education. I’d argue that parent involvement is the primary factor for student success in any edu

cational

6

venue” (para. 15). In her interview with Concordia University (2012), Martin-Chang went even further, suggesting

that public school teachers and parents can create the same benefits as homeschooling in traditional classrooms by

investing time in individual students and creating choice in the classroom. True changes to public school classrooms

will likely require other educational reforms, but the point is that the learning environment is more important than

the actual venue. Still, as public schools work and sometimes struggle to meet the needs of individual children, en

suring quality homeschooling experiences should be a priority in the state of Oregon and elsewhere.

7

References

Concordia University. (2012, November 6). Are home-schooled children smarter? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AGp4KFLuQNc

Hovde, E. (2013, January 5). Sorting out the truth and myth in home schooling. The Oregonian. https://www.oregonlive.com/hovde/2013/01/elizabeth_hovde_sorting_out_th.html

Joyce, K. (2013). The homeschool apostates. The American Prospect Longform. http://prospect.org/article/homeschool-apostates

Martin-Chang, S., Gould, O. N., & Meuse, R. E. (2011). The impact of schooling on academic achievement: Evidence from homeschooled and traditionally schooled students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 43(3), 195–202. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0022697

What is your overall impression of this essay? What do you think of its argument and tone? Do you think it is persuasive? Provide rationales for your responses.

What elements did you identify in the essay’s conclusion? What functions do these elements serve?

What do you think about this essay’s title? Can you make any suggestions to help the writer improve it? In addition, as a reader, what organizing/formatting feature might help you navigate the essay?

As you gather your thoughts and evidence for a researched argument essay, it may be useful to record your ideas on a graphic organizer, such as the one in Table 2, to make connections between your thesis, claims, evidence, reasons, and associated counterclaims, evidence, and reasons. Cells can be added to the table as needed to accommodate additional items.

Table 2. A graphic organizer for planning a researched argument essay

| My Research Question(s):

|

||

| My Thesis Statement:

|

||

| My First Claim: | My Evidence:

|

My Reason: |

| Counterclaim: | Counter-Evidence: | Counter-Reason:

|

| My First Claim: | My Evidence:

|

My Reason: |

| Counterclaim: | Counter-Evidence: | Counter-Reason:

|

| My First Claim: | My Evidence:

|

My Reason: |

| Counterclaim: | Counter-Evidence: | Counter-Reason:

|

A graphic organizer like the one in Table 2 can help highlight gaps in your work so you know how to proceed with your assignment.

What might cause an argument to fail?

By extracting meaning from the above graphic organizer and adapting information from Zickel (2018, p. 149), we can say that a thesis, claims, and reasons drive a sound argument, and quality evidence—that which is accurate, sufficient, relevant, complete, current, and credible—supports its development. On the other hand, an argument may falter when readers do not accept its evidence. Zickel (pp. 149-150) explains why that might happen.

- The evidence is inaccurate. The writer has either misinterpreted or misquoted evidence.

- The evidence is insufficient. Although the writer has used a small piece of evidence to support his/her reasoning, the paper needs more.

- The evidence is unrelated to the reason. In other words, the evidence does not clearly or directly relate to the point the writer is trying to make.

- The evidence is incomplete or is too narrowly chosen. The writer has selected certain examples or pieces of information to the exclusion of others, so while the writer does present evidence to support points, he/she also neglects other information.

- The evidence is old. The information is not relevant anymore because it is outdated.

- The evidence does not come from an authoritative source. Either the source of the evidence is not credible or the person cited is not an authority on the topic.

These evidentiary issues can result in a failed argument—one that does not succeed in its purpose by compelling readers.

In addition to the issues Zickel discusses, evidence can also fail to persuade if a writer simply strings it together without explaining it, pointing out its relationship to surrounding text in a paragraph, or connecting it to claims and reasons. Klassen and Robinson (2010, p. 1) provide an example to illustrate this type evidence fault.

This patchwork of quotations tells readers nothing about how the source material relates to the writer’s own thoughts. Juxtapose it with another sample, adapted from Klassen and Robinson (2010, p. 2), that uses the quotation sandwich approach to contextualize source information for readers.

When writing a researched argument essay, use the sandwiching approach with quotations, paraphrases, and summaries to establish connections between source material and your own ideas.

Evidence in a researched argument essay must also be ethically sourced, meaning it should be accurately quoted or sufficiently paraphrased or summarized, as well as cited and referenced. When evidence fails to adhere to these standards, it no longer provides solid support for an argument. To reinforce this idea, review the multipage handout in Figure 5, which has been produced by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System (n.d.). The handout lists original source material, incidences of plagiarism involving use of the material, and APA citations and references for the material.

Figure 5. Flaws in ethical source use

As Figure 5 indicates, flaws in ethical source use can be caused by plagiarism and inaccurate or missing source attribution. Now review Figure 6, adapted from the University of Alberta Library (n.d.), and decide how to update the citations and references listed in Figure 5 so they reflect APA seventh edition style as detailed on the infographic. If you prefer to look at an expanded version of the seventh edition style guidelines, refer to the “Reporting Research Outcomes” chapter of this textbook.

Figure 6. APA style guidelines (7th edition)

You can also use the infographic in Figure 6 to ensure your own papers align with APA seventh edition style.

Chapter Conclusion

We will draw this chapter to a close by reiterating a few of its key takeaways. Writers of effective researched arguments do the following:

- Narrow the focus and scope of their central arguments so they can adequately explain them in their essays.

- Make balanced cases about the topics they research.

- Adjust the strength of their claims as appropriate.

- Discuss their claims, evidence, reasons, and associated counterclaims, evidence, and reasons to fully develop the arguments conveyed in their thesis statements.

- Use convincing and credible evidence, and integrate it logically and ethically into their papers.

- Provide accurate in-text citations and accompanying reference list entries for the sources they use.

Use this guidance when composing your own researched argument essays to ensure they are maximally compelling.

Activity A: Explore Modes of Persuasion

Read the following information about modes of persuasion in arguments, adapted from the Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020b, “Modes of Persuasion”).

Over 2,000 years ago, a famous Greek teacher, scientist, and philosopher, Aristotle, taught his students that there were three basic ways of convincing an audience of something—or at least getting an audience to listen—and we still use these concepts today. You will often hear ethos, pathos, and logos referred to as the three modes of persuasion. Having an awareness of how to communicate convincingly using these modes will help you as you write argumentative essays.

Ethos

Ethos is the ethical appeal; writers use this appeal to convince readers of their credibility. Some credibility can be, in a way, built-in. A person’s level of education in relation to a topic may provide some built-in ethos. For example, if a psychology professor wrote an essay about the psychology of eating disorders, she would have strong, built-in ethos. But, if that same professor wrote a paper on quantum physics, her educational background would provide no built-in ethos.

If you have no built-in ethos, you can still establish credibility as you write. You can build your ethos, for example, by using credible sources and integrating them in an ethical manner. When you use expert research and opinion in your writing, you also draw on that material’s ethos to foster your own ethos.

Logos

Logos is the appeal to human logic, built via use of quality information in a paper and its coherent presentation. Having strong logos is a useful way to build ethos in an essay. For example, if you are writing a research paper on the plague in Medieval times, you will want to gather a good deal of research and then incorporate that research in an organized and effective manner. You should also discuss your points in a rational, balanced manner in order to avoid common logical fallacies [these are discussed in the next activity].

Pathos

Pathos is the appeal to human emotions. As a writer, your job is to make the audience feel connected with your topic, and this is where pathos can help. Think about the broad spectrum of human emotions: sadness, humor, pity, sympathy, anger, outrage; these are all things that motivate people. Pathos provides writers a tool to get readers emotionally invested in texts.

Although pathos is a powerful means of persuasion, it can also negatively affect credibility (ethos). Some readers may perceive its use as a form of manipulation and reject it completely because they do not want to be told how to feel about a topic. Furthermore, in academic and workplace writing, arguments are generally expected to emphasize credibility and logical reasoning more than emotion, and in many fields of study, perceptible emotion should be completely left out of writing.

As this text makes clear, ethos, logos, and pathos are interconnected. When you write a researched argument, think carefully about how these modes of persuasion might work together to create a solid essay.

Now work with a partner to identify what points discussed in this chapter demonstrate evidence of the modes of persuasion in use. How does the sample researched argument essay in this chapter demonstrate evidence of the modes of persuasion in use? Create a list of these points, and be prepared to discuss them in class. How might you use the list when preparing future assignments?

Activity B: Explore Common Logical Fallacies

Read the following information about common logical fallacies in arguments, adapted from the William & Mary Writing Resources Center (2018). By definition, “A fallacy is a breakdown of logic that uses faulty or deceptive arguments to reach a flawed conclusion” (McKeever, n.d.-b, para. 1). You should aim to avoid fallacies when constructing your own arguments.

Logical Fallacies

Example: Jack was late for his first two meetings with the professor. He must make a habit of being late.

Example: Jack finished that exam way earlier than everyone else. Either he knew all of the answers or none of them.

Example:When Jack suggested to his group project partner that her idea might not be feasible, she ignored his reasoning and accused him of being overly controlling.

Example: While writing a paper late at night, Jack hit a wall. In order to reach the minimum word count, he included a largely unnecessary summary of historical context, hoping that it would seem relevant.

Example: If Jack doesn’t turn in that paper tomorrow, he will receive a low grade, and then he will do poorly in the class. His GPA will suffer, he won’t get into grad school, and he’ll never achieve his dreams

Now work a partner to find an example of one of the fallacies in the news or in an advertisement; your instructor will ask different teams to focus on different fallacies. If you are unable to locate an authentic example, try to create one of your own. Be prepared to report back to the class about what your team did. How might this exercise help you avoid logical fallacies in your own writing?

Homework: Write a Researched Argument Essay

Identify a topic of inquiry you can explore via means of a researched argument essay. Your instructor may assign you a topic or ask you to select one. Research the topic by locating and reading sources about it. Afterwards, compose your essay using the guidelines presented in this chapter. Remember to cite and reference all outside sources you use in the paper.

You might begin exploring what you know about a particular debatable topic by using listing or mind mapping, two brainstorming processes. Here are descriptions of these processes.

Listing

- Take out a clean piece of paper and a pen.

- List everything that immediately comes to mind about a possible research topic.

- Review your list while looking for connections among its points.

- Decide whether any of those connections can be pursued through research.

Here is an example of a list focused on the topic of ebook readers, adapted from Pantuso et al. (2019, pp. 5.20-5.21).

- Ebook readers are changing the way people read.

- Ebook readers make books easy to access and carry.

- Books can be downloaded electronically.

- Devices can store hundreds of books in memory.

- The market expands as a variety of companies enter it.

- Booksellers sell their own ebook readers.

- Electronics and computer companies also sell ebook readers.

- Current ebook readers have significant limitations.

- The devices are owned by different brands and may not be compatible.

- Few programs duplicate the way people borrow and read printed books.

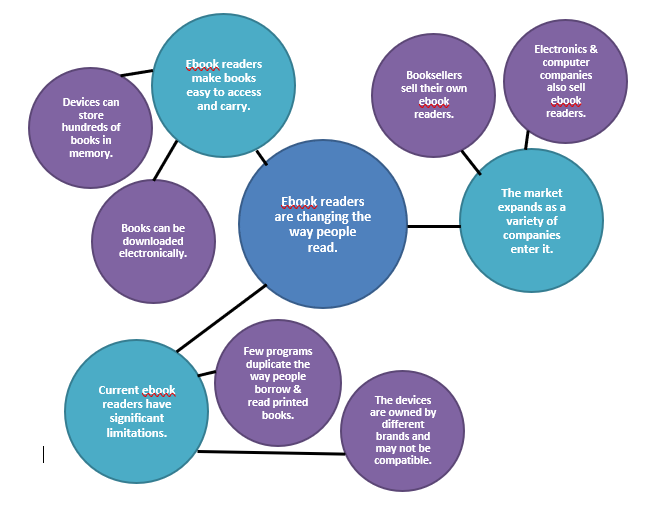

Mind Mapping

- Take out a clean piece of paper and a pen.

- Write your possible research topic in the center of the page and circle it.

- Write ideas associated with this topic in smaller circles around the main topic.

- Connect the smaller circles to the main topic with lines.

- Write ideas associated with the smaller circles around those items.

- Connect those ideas to the smaller circles with lines.

- Decide whether any of the connections can be pursued through research.

Here is an example of a mind map focused on the topic of ebook readers, adapted from Pantuso et al. (2019, pp. 5.20-5.21).

Once you have brainstormed ideas for your paper, researched your topic, and composed your text, use the following handout, produced by the Excelsior Online Writing Lab Writing (2020c), to revise your essay so that it is clear, concise, coherent, complete, and correct.

After you have written and revised your essay, your instructor may ask you to exchange papers with a classmate for purposes of peer review. You might use the following multipage peer review form, produced by the Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020a), for this exercise.

CARES peer review feedback form

References

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. (n.d.). Plagiarism & attribution APA style citation. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. License: CC-BY-NC 3.0. https://guides.library.uwm.edu/ld.php?content_id=6282964

Carey, E. (2020). Know more now guide: P.R.O.V.E.N. source evaluation process. Luria Library, Santa Barbara City College. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. http://libguides.sbcc.edu/ld.php?content_id=51820702

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020a). CARES peer review feedback form. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/03/CARES-Peer-Review-Feedback-Form.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020b). Modes of persuasion. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/rhetorical-styles/argumentative-essay/argumentative-essay-modes-of-persuasion/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020c). Revision checklist. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/RevisionChecklist2019.pdf

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020d). Sample Rogerian argument. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/organizing-your-argument/organizing-your-argument-sample-rogerian-argument/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020e). Sample Toulmin argument. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/organizing-your-argument/organizing-your-argument-sample-toulmin-argument/

Klassen, C., & Robinson, J. (2010). Building a paragraph around a quotation. Douglas College Learning Centre. License: CC-BY-SA. https://guides.douglascollege.ca/ld.php?content_id=35091489

Letessier, T.B., Mouillot, D., Bouchet, P.J., Vigliola, L., Fernandes, M.C., Thompson, C., Boussarie, G., Turner, J., Juhel, J.B., Maire, E., Caley, M.J., Koldewey, H.J., Friedlander, A., Sala, E., & Meeuwig, J.J. (2019). Remote reefs and seamounts are the last refuges for marine predators across the Indo-Pacific. PLoS Biology, 17(8), e3000366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000366

Lingard, L. (2020). The academic hedge part I: Modal tuning in your research writing. Perspectives on Medical Education, 9, 107-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-00559-y

McKeever, R. (n.d.a). Developing supporting arguments. Yuba College Writing & Language Development Center. License: CC-BY-NC-4.0. https://yc.yccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/DevelopingSupportingArgumentsRevAccessibleMay2020.pdf

McKeever, R. (n.d.b). Fallacies & emotional appeals. Yuba College Writing & Language Development Center. License: CC-BY-NC-4.0. https://yc.yccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/FallaciesAccessibleApril2019.pdf

McKeever, R. (n.d.c). Research papers, start to finish. Yuba College Writing & Language Development Center. License:CC-BY-NC-4.0. https://yc.yccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ResearchPapersAccessibleJune2020.pdf

McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph. (n.d.a). 5 questions to strengthen your thesis statement. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://learningcommons.lib.uoguelph.ca/item/5-questions-strengthen-your-thesis-statement

McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph. (n.d.b). 5 types of thesis statements. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://learningcommons.lib.uoguelph.ca/item/5-types-thesis-statements

Pantuso, T., LeMire, S., & Anders, K. (Eds.). (2019). Informed arguments: A guide to writing and research. Texas A&M University. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://acrl.ala.org/IS/wp-content/uploads/Informed-Arguments.pdf

University of Alberta Library. (n.d.). APA style citation reference list overview (7th edition). License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://guides.library.ualberta.ca/ld.php?content_id=35262329

William & Mary Writing Resources Center. (2018). Common logical fallacies. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://www.wm.edu/as/wrc/newresources/handouts/logical-fallacies.pdf

The Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Building strong body paragraphs. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/building_strong_body_paragraphs.pdf

Zickel, E. (2018). Failures in evidence: When even “lots of quotes” can’t save a paper. In M. Gagich, E. Zickel, A. Lloyd, C. Morgan, J. Lanning, R. Mustafa, S.M. Lacy, W. Breeze, & Y. Bruce, In practice: A guide to rhetoric, genre, and success in first-year writing (pp. 149-150). MSL Academic Endeavors. License: CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/