Operating in Online Courses

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

While attending college, you may take one or more online courses. This chapter aims to help you understand how online courses work, how crucial organization is to success in online courses, and what communication skills and reading strategies facilitate online learning.

How Online Courses Work

If you take a course online, you will be expected to engage with lessons, course materials, classmates, and your instructor in a virtual classroom rather than in a physical one. To encourage such engagement, many online college classes are delivered via course or learning management systems, which provide various software tools and digital environments for interactions (Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University, 2019, para. 1). This type of system may offer some of all of the following features (adapted from Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University, 2019, para. 1):

- Space for an instructor to post course materials, such as lesson handouts, multimedia presentations, assignment specifications, readings, the syllabus, class policies, rubrics, and the class schedule.

- Submission spaces, which are sometimes linked with text-matching detection software, where students can post assignments and review feedback.

- A gradebook where an instructor can record grades and students can view their marks.

- An email tool that allows course participants to send messages to the entire class or to a subset of the class.

- A chat tool that allows for synchronous communication (real-time communication) among course participants.

- A discussion board that allows for asynchronous communication (time-lapse communication) among course participants.

This type of system helps to organize what happens in online courses, and, as long as you have access to the internet, you should be able to access it on any digital device. Learn how to use this type of system when a course begins so that you can function effectively during the semester; if you struggle, reach out to the learning or computer support team at your university, or ask your instructor for guidance.

Myths and Realities of Online Courses

Let us now consider a number of myths and realities of online courses, which are adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016b, “Common Myths”). While reading, consider how your own viewpoints about online courses relate to the information provided.

MYTH 1: I’ve heard that the online course is way easier than taking the same course on campus. You don’t have to go to class—you just have to hand in assignments and you’re done.

The Reality: The workload for a course is oftentimes the same regardless of the way it is delivered. However, online classes typically involve more reading because you have to read all of your teacher’s instructions rather than hearing them in class. In an online environment, you also need to be self-disciplined and motivated to complete work because you will not see your instructor every session.

The good news is that online classes will give you the flexibility to study at times that work with your schedule. This factor can benefit students with busy lives who are trying to juggle school, work, family, and other responsibilities. Plus, in an online class, you are not limited by class times, so you do not have to worry about conflicts with other classes.

MYTH 2: If I’m taking an online class, I can submit assignments whenever I want. I’ll just get all the assignment directions from the instructor right away and fly through the class in two weeks rather than wasting a whole semester.

The Reality: Most online college courses are not self-paced. Some instructors reveal all the assignments ahead of time, while others communicate course topics and assignment directions incrementally. The key is to follow the pace the instructor establishes. Give yourself time to focus on the course material, and dedicate time and effort to assignments—do not try to rush through the course just to get it done. In short, the more you put into an online (or face-to-face) course, the more you will get out of it.

The good news is that students who have successfully completed online courses have found that the organizational skills they used in those courses helped them to function more effectively in face-to-face courses.

MYTH 3: Instructors randomly call on students for answers during face-to-face classes, but in an online class I can zip through unnoticed.

The Reality: Please do not be fooled by the illusion of anonymity in a virtual classroom. Even though you and your instructor may not be able to see each other, the instructor can access data about the quantity and quality of your course participation. Instructors want to know how students are doing, what they are doing, and how they perceive the class, so participation is a key component of any class.

The good news is that online learning provides an opportunity to develop a meaningful relationship with your instructor and classmates. In an online course, everyone has a chance to provide input, and you have time to craft your thoughts before engaging in discussion. Another benefit of online learning is that your participation is not bounded by the end of a class period.

MYTH 4: Email means instant communication, and I know my teacher checks her email all the time. This means that if I don’t understand something or have a last-minute question about an assignment, I can email her and she will respond right away. She’s definitely up at 10:00 pm, and it would only take her two minutes to write back with an answer.

The Reality: Most instructors provide a maximum email turnaround time, typically between 24 and 48 business hours. As a responsible student, you need to plan ahead as much as possible by having an alternate solution if you do not hear back from your instructor before an assignment is due. Some instructors arrange a discussion thread in their course or learning management systems where they encourage students to answer one another’s questions. Another option would be to reach out to a classmate and exchange private emails to support each other throughout the semester. Because you are not meeting in person with others every week when taking an online course, you might feel a bit isolated. The tactics outlined here offer ways to connect with others in the course.

The good news is that students who develop effective communication methods, learn to take personal responsibility for their own work, and are able to cooperate and collaborate well in a virtual environment will find these skills highly transferable and valued in their personal and professional lives long after an online course is over.

MYTH 5: If I didn’t finish an assignment on time, I used to tell my instructor that I accidentally brought the wrong notebook to class or that my printer ran out of ink. Now I can just say that my computer crashed, that I accidentally deleted my finished assignment, or that I just sent in the wrong attachment.

The Reality: Do not rely on excuses to get by in college. Most instructors have heard excuses before and can determine when students are being untruthful. Make sure you fully understand your instructor’s expectations, which will likely be communicated on the course syllabus, and comply with them in a timely manner. Some instructors provide checklists for meeting deadlines; if your instructor does not, create your own assignment checklists. In addition, maintain communication with the instructor if you need help or have questions.

The good news is that the organization and study skills you hone while taking an online course can support your success in future courses, whether they are in online or face-to-face learning environments.

Have you ever taken an online college course? How does the information about myths and realities of online courses resonate with your own experience as a college student?

Online Courses Demand Organizational Skills

If you are taking or are considering taking an online course, know that such courses demand organizational skills on your part. For example, in a face-to-face learning environment, the instructor will likely remind students multiple times about deadlines for homework and papers, required reading assignments, and dates for quizzes and exams; however, students have keep up with such things themselves when operating in online environments. Use the following guidance, which is adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016d), to think about organizational techniques you might use when taking an online course.

Organize Your Environment

Before you jump into an online course, identify your study preferences. Use the information presented to answer the questions about your study preferences.

Some individuals feel that they are most alert and fresh in the mornings, while others prefer to work at night after they have finished other things they need to do during the day. Identify what time of day works best for your studies, and create a schedule to stay on track with your coursework. What time of day are you most productive?

Some students prefer to work at home; others find that setting too distracting. Some prefer the quiet atmosphere of a library, while others appreciate the background activity of a café. Be sure to have a secondary study location in mind in case your first location is not available on a certain day. Also, know where you can plug in digital devices when the need arises, and identify several places with free wireless internet in case the network goes down in one spot. Where will you study?

Motivation can be influenced by noise level, temperature, thirst, and hunger, for example, so plan to bring earplugs, a sweater, a drink, food, and anything else you need to your study space in order to focus on coursework. What conditions will enable you to concentrate most effectively in your study space?

Organize Your Course Materials

When taking on online course (or any course for that matter), you will also need to decide how to organize your class materials. Some students like to work with printed copies they can write on, while others appreciate the ease and flexibility that comes with digital copies. Some students use a combination of both, depending on the course or assignment. Regardless of your preferences, set up a reliable and convenient system to manage things you will need for your course.

If you like to work with printed copies, find a place where you can keep together all your school materials and supplies: books, notes, assignments, binders, pens, highlighters, paper, a stapler, a hole punch, and a calendar.

If you like to work with electronic copies, you will need to identify a place where you can store these. You may want to store files on your personal computer or on a flash drive. Alternatively, you might decide to email assignments or papers to yourself and use cloud (online) storage to keep and organize files. In the latter case, check cloud-service websites for capacity limits (how much space they provide), compatibility details (what browsers they support), and features that will offer you the most value for money.

Keep at least one backup of each of your files, and store them in different places for added security. For instance, if you save your files on your personal laptop, also save them on a flash drive or in cloud storage; that way, if your computer crashes, you will still have your work.

Organize Your Time

When you enroll in an online course, be sure to read the syllabus thoroughly and become familiar with requirements and due dates. Write these down to get a sense of what the semester will look like and the pace of the course. Better yet, create a schedule or calendar that you can consult and update periodically throughout the semester. If you prefer to break an assignment into manageable pieces and schedule them accordingly, then do so. The incremental deadlines you set will establish milestones for achievement and allow you to monitor your own progress on projects.

What organizational techniques do you currently use as a student? What might help improve the organizational techniques you currently use?

Communication Skills for Online Learning

Students commonly have questions about communicating in online courses. The following information, which is adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016a, “Netiquette” – “Email Netiquette”), might help resolve your own uncertainties about this topic.

STUDENT 1: What do the differences between synchronous and asynchronous communication mean for me when taking an online course?

Answer: Online class communication often takes place asynchronously rather than in real time, giving you a chance to research, write, and edit your work instead of being asked to respond immediately to a question. Think of this as an opportunity to compose your thoughts carefully before making a response.

Synchronous sessions are similar to what you may experience in a face-to-face class. Discussions may be lively when working in this mode because interactions are immediate since everyone is in the virtual classroom at the same time. These types of interactions can also help establish class bonds.

STUDENT 2: Will my online communications be permanent?

Answer: Yes, when you communicate asynchronously online, you create a permanent record of your words. All of your electronic communication will be dated, and because of this, it can be easily organized, stored, and reviewed at a later date. Because words are enduring, it is a good idea to compose your electronic communications carefully before posting.

STUDENT 3: I generally feel more comfortable talking online than in person. Is online communication easier than face-to-face communication in a classroom?

Answer: It can be. When you communicate through email, private messages, a discussion board, or a blog, your instructor and classmates may not know much about your individual characteristics. Some students find that this environment gives them extra confidence if they are normally shy or nervous in front of instructors or other students.

STUDENT 4: I am worried that there will be more potential for misunderstanding when I’m communicating online than when I’m communicating in person.

Answer: This is a valid concern because the teacher and your classmates cannot see your body language or hear your voice, and written words can sometimes be misinterpreted. Review your written communications in an online course carefully before posting, and remove any language that could be construed as offensive or inappropriate.

STUDENT 5: Can I make friends in an online course?

Answer: If you are normally reserved in front of people, you may feel like you can express your ideas more freely in an online environment. Discussion boards and blogs often create a sense of community as you respond to your instructor’s and classmates’ comments and they respond to your posts. In an online course, everyone has a chance (and is expected) to speak.

STUDENT 6: Can you give me some tips for writing effectively in an online educational environment?

Answer: Effective writing skills are vital in online courses to communicate your points. Here are some specific suggestions for crafting online written communication.

-

- Check your writing for spelling, grammar, capitalization, and punctuation errors.

- Keep your posts clear and concise.

- Avoid slang, offensive language, and personal attacks.

- Look for opportunities to interact and collaborate with other students in the course. If you draft a negative comment in response to someone’s post, reframe it in a way that is more conducive to creating discussion. Keep in mind that it is fine to disagree with someone’s views as long as your tone is respectful.

STUDENT 7: How do I go about writing a respectful discussion post?

Answer: First, make sure that you read your instructor’s directions and follow them carefully. This is the most basic way to show respect for your instructor and others in the virtual classroom. Second, when your instructor posts topical questions to a discussion board and requests your informed response, take the time to compose text that is carefully written, and edit and revise your contribution before posting it.

The term netiquette refers to network etiquette, or the correct or acceptable code of conduct for communicating online. Netiquette includes using respectful behavior and language and acknowledging other people’s privacy interests. Netiquette conventions apply to discussion posts and emails sent for purposes of an online or face-to-face course.

STUDENT 8: How do I demonstrate netiquette when emailing classmates or an instructor?

Answer: Be sure to respond to email in a timely manner, and give others sufficient time to respond to your messages. Abide by any guidelines your instructor gives regarding time-frames for responses.

In addition, if you include an attachment with your email, mention it in the body of the message. Double-check that you have included the attachment before you send the message.

Lastly, read your email messages carefully and revise any errors you detect before sending them.

Taking into account the questions and answers about online learning, help Brittany compose an email to her instructor asking when the midterm will take place. Select the correct option for different segments of the email.

- The salutation

- Dear Professor Kennedy,

- Hi,

- The question

- do u kno when the midterm will b? thx

- I hope you’re well. I was wondering, do we have a set date for the midterm?

- The wrap-up and sign-off

- Thanks for your help. Sincerely, Brittany.

- THANKS SO MUCH!!!!!

Now supply a rationale for each for your choices. Refer to the information presented in this section of the chapter for guidance.

Discussion Boards for Online Learning

A course discussion board provides an opportunity to engage with classmates, an instructor, and course content in an active way; still, effective discussion board communication hinges on participants’ positive, productive, and substantive engagement in discussion posts. The following list, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020c), raises points to consider when undertaking discussion board work.

- Review the purpose of the discussion. Is there a particular question you are expected to answer? Is the discussion space intended to be a place for you to ask questions? Make sure you are responding as expected in the discussion space.

- Work with the background reading required for the discussion. Annotate the text with your own ideas and questions as you read; summarize the main ideas to test your own understanding; and stretch your understanding by applying concepts and theories to new contexts. Most discussions are designed as spaces to test out and debate ideas.

- Recognize that discussion is a give-and-take situation, a conversation. That means that you should participate frequently during discussion, offering your own ideas and responding to others. You can enter the conversation at different points, with ever-changing purposes and roles, but you need to be there on a consistent basis.

- Realize that each participant can choose from among many discussion roles and functions. You can post initial ideas, respond to ideas, summarize ideas, point out similarities and differences or trends among ideas, ask questions, add examples, extend the conversation in different directions, and bring the conversation back on point if it digresses.

Abiding by these guidelines will help to make your discussion board experience a constructive one.

Using information adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020a), we can explore ground rules for discussion board work.

- Use a specific subject line. Using a phrase such as “response to Amir” for your subject does not tell other readers anything about the content of your response. Be brief, yet specific (e.g., Errors in Watting’s Theories).

- Keep to one main idea or topic per response. If you want to comment on two different ideas, write separate posts.

- Differentiate between starting a discussion thread and responding to someone else’s posting. Most discussion boards use a threaded discussion, which means that responses are indented under an initial posting. This type of indentation provides a visual cue for readers, allowing them to rapidly distinguish the different discussion topics or threads.

- Check your spelling before you finalize the posting. Most systems have a spell-check function. You may want to compose your response with a word processor and then paste or upload it into the discussion board. This is also a good idea in case there are technological issues, which can cause you to lose a post. If you create your post in a word-processing program, you can save a back-up copy of the text.

- Do not dominate the discussion. You do not need to respond to every posting from every participant. Respond selectively instead. Instructors will often establish how much online participation is expected.

- Be polite, and apply the rules of etiquette. Use standard capitalization and punctuation. Do not use all caps, as this is considered shouting; instead, use italics sparingly to emphasize points.

- Remember that many people may have access to your posts on a discussion board— other students, your instructor, college technology staff, and administrators—so write accordingly.

When grading discussion board posts, your instructor may feedback on spelling, capitalization, punctuation, sentence structure, word use, citation and referencing, and other writing matters, so be sure to attend to these issues when composing your texts.

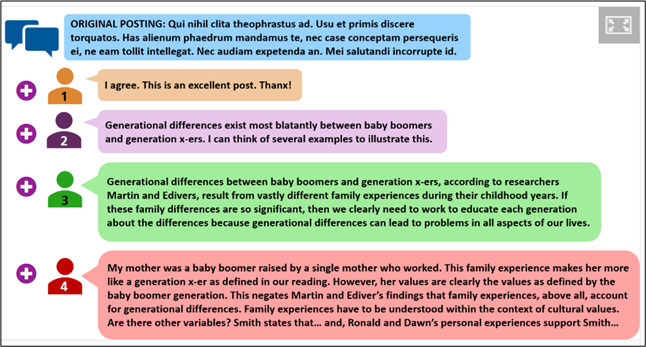

To illustrate the nature of effective discussion board content, we will examine several comments posted in a discussion thread and consider feedback that might apply to them. To begin, read the thread in Figure 1, excerpted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020b).

Figure 1. Example discussion board thread

Having read the discussion board comments, match the appropriate piece of lettered feedback (adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020b, “Activity Transcript”) to each numbered comment.

- The student does not offer new insights or details about why he/she agrees with the post and includes a misspelled word.

- The student makes a connection to the class reading, offers a viewpoint on it, gives reasons for the viewpoint, and makes connections to new research.

- The student refers to classroom reading and makes a connection to experiences and observations.

- The student offers a new, specific idea, but does not develop it.

Which post is most likely to inspire a quality discussion? Record your answer and rationale in the box provided, and be prepared to discuss your ideas in class.

Can you think of any other pieces of advice that might help to inspire substantive and constructive discussion board content beyond the points covered here?

Reading Strategies for Online Learning

Expect to do a considerable amount of reading when enrolled in an online course, including reading of webpages, online documents, textbook chapters, printed articles, discussion posts, homework directions, assignment feedback, and emails. The following information, which is adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016c, “Print vs. Online” – “Why, What, How?”), is intended to help you develop reading strategies for online learning.

Print versus Online Reading

Reading printed material is different from reading online. First, when you read something that has been printed by a reputable publishing house, you might make assumptions that the work is authoritative because the author had to be vetted by the publisher and multiple editors. In contrast, online materials can be written or posted by anyone, which means you have to carefully evaluate the authority of the information presented, for instance, by determining who the author is and what qualifies that person to write on the topic. Second, in the print world, texts may include figures, tables, or other visual elements to supplement the author’s writing; in the digital realm, hyperlinks, audio, and video may also be embedded in the text, which changes the reading experience since online texts can be interactive in ways that printed material cannot. While these features of online texts allow readers to interact with content in an active way, they can also be distracting: rather than reading the text, some individuals might be more interested in clicking on hyperlinked items, which decreases time spent focusing on the material. Lastly, when reading printed material, you generally read sequentially, from the first word to the last. Maybe you will flip to an index or reference page, but otherwise the way you read is fairly consistent and straightforward. When reading online, you can quickly be led into an entirely new area of reading by clicking on links.

As hinted at, the differences between reading print and online material have some practical consequences for reading comprehension, or how you understand and apply what you are reading. Ask yourself these questions when reading online to focus on the why, what, and how of reading comprehension.

- Why? Why am I being asked to read this material? In other words, what instructions has my professor given?

- What? What am I supposed to get out of this material? That is, what are the main concerns, questions, and points of the text?

- How? How will I remember what I just read? In many cases, this means taking notes and defining key terms.

Applying the why, what, and how questions to your online reading may help you comprehend the material and its purpose, retain important points, and structure your notes for future reference.

Questions and Answers about Online Reading

The following questions and answers, adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016c, “Student Q&A 1” – “Student Q&A 3”), may address lingering uncertainties you have about reading online.

QUESTION: I’m so used to reading printed texts, and I actually prefer them because I don’t get distracted as easily as I do when I’m online. So how can I keep from getting distracted when reading online?

Answer: When you read online, the hyperlinks, images, audio, and video interactivity embedded in the text can be a tempting distraction. Try reading a passage through at least once without clicking on any of the hyperlinks or participating in any of the interactive opportunities. In other words, get a basic feel for the passage, and then read it with the interactive components to augment your reading experience.

QUESTION: I once had a teacher who didn’t want students to use their phones to read assigned texts. Why did he care?

Answer: Avoid reading your assignments on a small phone screen because you may miss words, meanings, and content.

QUESTION: How can I improve my online reading speed?

Answer: To read more quickly and efficiently online, avoid distractions like advertisements, pop-ups, and hyperlinks that will lead you away from the assignment. In addition, scan the page before actually reading it by focusing on keywords and phrases, headings, visuals, and topic sentences.

An Online Reading Activity

Now that you have considered some of the facets of online reading, put the information to use by working with a partner during class time to complete the following exercise, which is adapted from Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges (2016c, “Explore a Web Page”).

Imagine that your instructor has asked the class to write an argument paper that either supports or opposes the death penalty in your state. She has pointed students to the website www.deathpenalty.org as a starting place for research. Upon checking this website for information, you see a number of potential sources for your paper, which are listed below. Which articles seem like they might work best when getting started, and why? Look carefully at the titles or headlines to help determine which sources offer the best potential leads for your paper. Be prepared to discuss your responses with the class.

- An article entitled “Federal Judge Says State Death Penalty Unconstitutional”

- An article entitled “Lawyer Michael Millman Accepts Lifetime Achievement Award for His Work with Indigent Death Row Inmates”

- An article entitled “The Death Penalty Failure They’re Trying to Hide”

- An infographic entitled “The First Time We Ended the Death Penalty”

- An article entitled “Polls Show Preference for Death Penalty Alternatives”

- A testimony from someone affected by the death penalty provided in a blog post entitled “How to Stop a Heart”

- An article entitled “Former Florida Warden Haunted By Botched Execution”

- An article entitled “Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Appoints New Director of Community Outreach and Education”

Homework: Apply the Reading Comprehension Questions Discussed to an Online Text

Read an article published on the National Public Radio website entitled “Fake or Real? How to Self-Check the News and Get the Facts” (Davis, 2016), which can be found at https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/12/05/503581220/fake-or-real-how-to-self-check-the-news-and-get-the-facts. Take notes on the following questions as you read.

- Why am I being asked to read this material?

- What am I supposed to get out of this material? That is, what are the main concerns, questions, and points of the text?

- How will I remember what I read?

Having taken notes on the article, now compose an email to your instructor in which you do the following:

- Discuss your answers to the reading comprehension questions.

- Discuss how you will use the information presented in the article moving forward.

Apply standard conventions for professional emails when completing this task, and cite and reference any outside sources of information you use. Consult the “Writing Electronic Correspondence” chapter of this textbook for guidance when composing your message.

Remember to edit, revise, and proofread your message before sending it. The following multipage handout, produced by the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d.), may help in this regard.

Subject-Verb Agreement

Subject-verb agreement involves using the right verb form for the noun that holds the subject position in your sentence. If the grammatical subject of your sentence is singular, you use a singular verb form; if it is plural, you use the plural verb form. Subjects and verbs are said to disagree when verb endings do not correspond to the subject.

Verb Endings

Personal endings for regular English verbs:

I walk

You walk

She/he/it walks

We walk

You (plural) walk

They walk

Note that the only time you need a different ending is with the third person singular form. You also need to consider different forms with some common irregular verbs:

I am

You are

She/he/it is

We are

You (plural) are

They are

I have

You have

She/he/it has

We have

You (plural) have

They have

These common irregular verbs are especially important because they are also auxiliary verbs:

She is walking to school.

She has walked to school.

They are walking to school.

They have walked to school.

Common Errors in Subject-Verb Agreement

Errors in subject-verb agreement occur much more frequently when sentences become more complicated. Be careful of the following tricky situations:

When there are several words between the subject and verb. The tendency is to make the verb agree with the closest noun, which is not correct.

Incorrect

e.g., The reliability of many standard intelligent tests have been challenged in recent years.

The subject of this sentence is reliability so the verb should be has been challenged.

When the subjects are compound, that is, when two singular subjects are joined by and (A and B) to form a plural subject.

Incorrect

e.g., The high cost and extreme difficulty of implementing the project was cited in the explanation of its cancellation.

The subject here is high cost and difficulty (two things) so the verb should be were cited.

When the subjects are who, which, or that (the first words in adjective clauses).

Incorrect

e.g., Elena is one of the many students who has benefitted from the services of the Writing Centre.

In this sentence, the word who is a pronoun that refers to plural students, so the verb should be have benefitted.

When the subject comes after the verb as in inverted sentences.

Incorrect

e.g., Under the table was several empty beer bottles and various dirty socks.

In this sentence, although the subject empty beer bottles and various dirty socks comes

after the verb was, it is still plural so the verb should be were.

When the subject is a collective noun (team, audience, class, family, etc.).

Collective nouns are especially tricky because they can be singular or plural, depending on the context.

Collective nouns are followed by singular verbs when the members of the group are functioning as a single entity, and by plural verbs when they are functioning as individuals within the group.

e.g., The class is writing the exam.

In this case, the class is functioning as a unit, so the verb is singular.

e.g., After the exam, the class go their separate ways.

In this case, the individuals in the class are doing different things, so the verb is plural.

References

Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University. (2019). Course management systems. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/course-management-systems/

Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges. (2016a). Communication skills for online learning (text version). License: CC-BY. https://apps.3cmediasolutions.org/oei/modules/communication/text/

Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges. (2016b). Introduction to online learning (text version). License: CC-BY. https://apps.3cmediasolutions.org/oei/modules/intro/text/

Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges. (2016c). Online reading strategies (text version). License: CC-BY. https://apps.3cmediasolutions.org/oei/modules/reading/text/

Chancellor’s Office, California Community Colleges. (2016d). Organizing for online success (text version). License: CC-BY. https://apps.3cmediasolutions.org/oei/modules/organizing/text/

Davis, W. (2016, December 5). Fake or real? How to self-check the news and get the facts. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/12/05/503581220/fake-or-real-how-to-self-check-the-news-and-get-the-facts

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020a). Discussion boards. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/online-writing-and-presentations/discussion-boards/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020b). Discussion board content. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/online-writing-and-presentations/discussion-boards/discussion-boards-content/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020c). Discussion board style & structure. License: CC-BY. https://owl.excelsior.edu/online-writing-and-presentations/discussion-boards/discussion-boards-style-structure/

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Subject-verb agreement. License: CC-BY-SA. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/subject-verb_agreement_0.pdf