Choosing Integrity

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

This chapter aims to help you understand what academic integrity is, how to use sources ethically, and how to avoid plagiarism and its consequences. Plagiarism is defined as using someone else’s text, language, ideas, content, or visuals without acknowledging the source.

What is academic integrity?

Vital to success in college is the ability to demonstrate academic integrity, a term that can be viewed from a number of different perspectives, as the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) makes clear. This organization, which promotes academic integrity initiatives around the world, defines the term “as a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage” (ICAI, 2017, para. 1). The ICAI emphasizes that students can add worth to their own assignments by upholding these values (ICAI, 2013, p. 16) and explains how the values impact academic work. Specifically,

- “Academic communities of integrity advance the quest for truth and knowledge through intellectual and personal honesty in learning, teaching, research, and service” (p. 18).

- “Academic communities of integrity both foster and rely upon climates of mutual trust. Climates of trust encourage and support the free exchange of ideas which in turn allows scholarly inquiry to reach its fullest potential” (p. 20).

- “Academic communities of integrity establish clear and transparent expectations, standards, and practices to support fairness in the interactions of students, faculty, and administrators” (p. 22).

- “Academic communities of integrity value the interactive, cooperative, participatory nature of learning. They honor, value, and consider diverse opinions and ideas” (p. 24).

- “Academic communities of integrity rest upon foundations of personal accountability coupled with the willingness of individuals and groups to lead by example, uphold mutually agreed-upon standards, and take action when they encounter wrongdoing” (p. 26).

- “To develop and [sustain] communities of integrity, it takes more than simply believing in the fundamental values. Translating the values from talking points into action—standing up for them in the face of pressure and adversity—requires determination, commitment, and courage” (p. 28).

While facilitating an activity at Montana Technological University, the institution’s writing instructors found that students, faculty, and staff expanded the ICAI’s definition in various practical ways, as the following responses illustrate.

- Activity prompt: What does academic integrity mean to you?

- “Doing the right thing at the right time or getting help if you need it.”

- “It means always doing your own work and asking for help instead of cheating.”

- “Doing the right thing when no one is watching.”

- “Assigning credit to the author of any work.”

- “Respecting yourself [and] your school.”

- “Completing your own work honestly.”

- “Being honest [with] yourself [and] those around you [at] all times.”

- Activity prompt: When people demonstrate academic integrity, they…

- “Take pride in their own work by completing the work themselves.”

- “Ask for help from their professors when they need it.”

- “Academic integrity means being honest, earning your grade through hard work, and appreciating yourself and your accomplishments.”

Having read through how others define academic integrity, how would you interpret it? In other words, how would you respond to the activity prompts? Record your answers below.

What activities violate the ICAI’s definition of academic integrity? Record your answers below.

As the discussion in this textbook section indicates, academic integrity influences and impacts much of what happens in college.

How does a writer use sources ethically?

Most college writing assignments require that students use sources to support their ideas. When using sources, writers first locate resources, such as news articles, journal articles, books, reports, and visuals, and then integrate information from the sources into their writing to reinforce, illustrate, and expand upon their points.

To demonstrate academic integrity when using sources, including visuals, writers must acknowledge the origins of the source information in their writing to give its creators credit for producing the work. Although writers may acknowledge sources of information somewhat differently when producing various types of texts, much academic and workplace writing uses citations and references for this purpose. An in-text citation is how a source is referred to in the body of a document; an accompanying reference list, which is placed on a separate page at the end of a document, provides full bibliographical details for the in-text citations. Hence, citations and references are linked since every reference list entry must have a corresponding in-text citation.

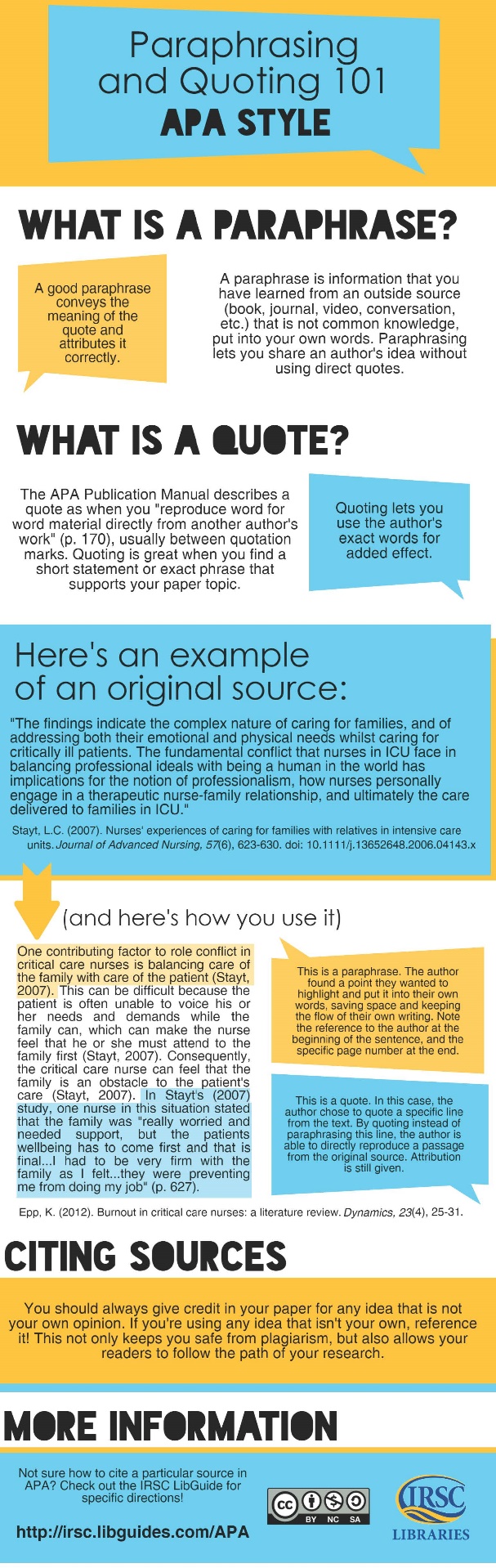

Writers can integrate source information into their documents through quotation, paraphrase, and summary. Quoting means to use the exact words from a source; those words must be enclosed in quotation marks (“ ”), and the quotation must be cited and referenced to document its origin. Paraphrasing, in contrast, means to express the meaning of a source text in a writer’s own words. An unacceptable paraphrase is one that simply replaces source language with synonyms. When writing an acceptable paraphrase, a writer thinks carefully about what the original text says and then articulates the text’s meaning without looking at the original. The writer also provides an in-text citation and reference for the paraphrased material. Although paraphrasing and summarizing are related, a summary focuses only on a text’s main point and excludes any details. A writer summarizes by reading the source text, identifying its main point, articulating the main point without looking at the original, and citing and referencing the source. A summary tends to be shorter than the original source text being summarized because it omits details, whereas a paraphrase is roughly the same length as the original text because it includes details.

When producing written communication in the workplace, employees sometimes extract sections of text from their own companies’ reports, internal manuals, or news releases for use in other company documents to communicate messages in a time-efficient and consistent fashion. The employees are permitted to use this repurposed text, also known as boilerplate, without citations, references, or quotation marks because the company owns the text its employees generate on the job.

The following infographic, produced by Indian River State College Libraries (2019), provides further detail about paraphrasing, quoting, and citing. Infographics combine text, visuals, and numbers to communicate dense information in quick and easy-to-read formats. Read the infographic carefully, and answer these questions about it.

- According to the infographic, why should writers cite and reference sources?

- According to the first sentence of this textbook section, why should writers cite and reference sources?

- What other reasons can you think of for citing and referencing sources?

- Why might an infographic be a useful tool for reaching a general audience of readers?

Draw upon the information in this infographic and textbook section to use sources ethically when completing your own work.

What constitutes plagiarism?

To help you understand what constitutes plagiarism, review another infographic produced by Turnitin, a company that sells text-matching detection software and conducts research on academic integrity topics. While reviewing the infographic entitled “The Plagiarism Spectrum” (Turnitin, 2016), which can be found at https://www.turnitin.com/static/plagiarism-spectrum/, notice what kind of activities are classified as plagiarism. What do you find surprising about the infographic?

The following case studies, which are adapted from Lumen Learning’s online course English Composition (n.d., “Defining Plagiarism”), detail other instances of plagiarism. Review these case studies.

Plagiarism Case Studies

Case 1:

Last semester you wrote an essay on Emily Dickinson for Professor Berlin’s American Literature 101 course. This semester you are taking a course called Interrogating Gender in American Culture, and Professor Arecco has assigned a paper topic that references Dickinson’s life and work. It would be very easy for you to re-tool whole sections of your first essay to satisfy the requirements of the second, and you wonder whether it is acceptable practice to re-submit this paper, without checking with either professor, because you are writing a paper for a different professor and a different course.

In reality, you must check with both Professor Berlin and Professor Arecco before re-submitting this paper. If you were to superficially revise this paper and submit it without prior approval from both professors, you would be committing self-plagiarism by dual submission; when you are given an assignment in college, the expectation is that you will fulfill the requirements of the assignment by completing new work. If you are given permission to build upon a previously completed assignment to develop another assignment, your professor may require you to acknowledge this situation in your paper, possibly by citing and referencing your previous work.

Case 2:

You are writing a biology report and you have included information that you read in your biology textbook. You are not sure if this information can be considered common knowledge, or whether you need to cite and reference it.

In reality, you should cite and reference the textbook regardless of whether you quote from it directly. While it is not necessary to give citations/references for certain well-known equations, it is important to acknowledge your debt for any information you did not create independently.

According to information adapted from Penn State University (2017b, “Unintentional Plagiarism – How to Properly Cite a Reference”), the term common knowledge refers to any knowledge you can reasonably expect other people to know. For instance, the fact that there are bilingual speakers in the United States is common knowledge. In this situation, you would not have to cite any sources. However, the specific number of bilingual speakers in the United States is not common knowledge. So if you were using any graphs or lists to detail this information, you would need to cite and reference where you found it.

Case 3:

You have cut and pasted information from articles you found on websites into a Word file on your computer. While writing your essay, you patch together pieces from different sources and occasionally lose track of which ideas are your own and which are from various articles. You consider going back to the original sources, but the prospect is daunting. In any case, you figure that if your professor queries your sources, you can say you did not intentionally plagiarize and this will result in a lesser punishment.

In reality, unintentional plagiarism is still intellectual theft, and poor note-taking skills are not a mitigating circumstance when punishment is decided. Here are some tips for avoiding unintentional plagiarism. If you take notes on a computer rather than on paper, create a special folder for citation information. In fact, it would be a good idea to create a number of folders: one for your paper, another for sources, and another for the notes you take from each source. Maintain all the information for the reference list as you go, and even complete citations and references as you are writing to save time and effort later. When taking notes, identify your sources, enclose direct quotes in quotation marks, and duplicate every punctuation mark. Avoid using the author’s language when paraphrasing or summarizing information, unless, of course, you quote verbatim from the original. Here is a tip for keeping your ideas separate from those in your sources: either identify each idea as your own, that is, cite yourself, or use a different color or font for your ideas on screen. In addition, print out your sources whenever possible, even when you have a file version on your computer. Working from the paper sources will allow you to check quotations for accuracy.

Case 4:

Your professor has assigned a researched argument essay. While looking through a book, you find a quotation that seems to apply to the argument topic, and you plug it into your essay; however, it does not quite relate to the point you addressed previously in the essay, and you do not know how to discuss it. You realize you do not fully understand what the quotation means or how to write about it within the larger context of your essay. You think of approaching your professor to ask for help, but decide that she will think less of you for not grasping the meaning of the text. Instead, you find a website that discusses the idea mentioned in the book, and you summarize its explanation in your paper without citing it. Is this plagiarism?

In reality, even if it is a website, and even if you are summarizing rather than quoting or paraphrasing from the site, you are still using someone else’s ideas without acknowledgement. A summary is written in your own words, but it still makes reference to another person’s intellectual property. Think of it this way: you are collaborating with the authors of your sources, working with their ideas, and recasting them to develop your own. Finally, never hesitate to ask your professor for help. A professor should be your first and best resource for questions about texts or anything related to your class.

Case 5:

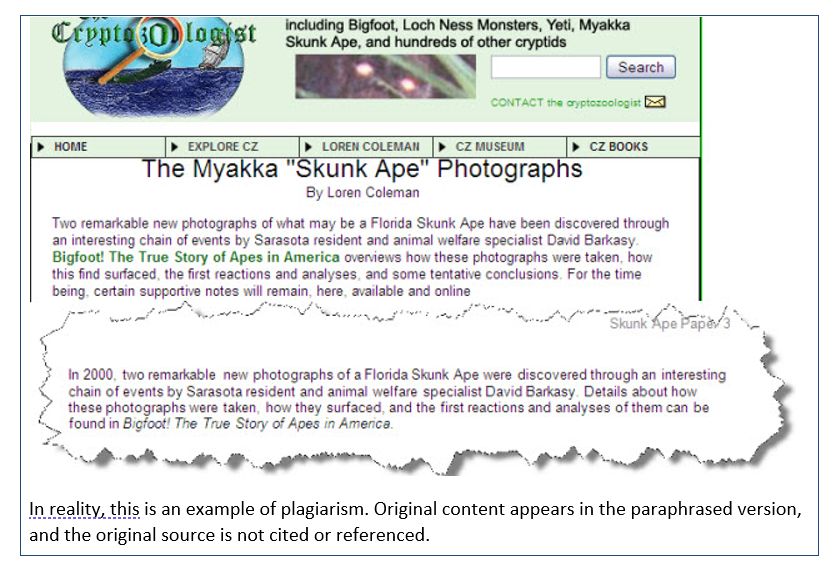

Is this use of information from a website plagiarism?

Image from Lumen Learning under CC-BY-SA License.

What do you find surprising about the five cases you read?

Now read another case, adapted from a document adapted from a document entitled “Scenario Resource: Sharing or Cheating” (Contract Cheating and Assessment Design, n.d.b, paras. 2-3).

Case Study: Sharing or Cheating?

In pairs or small groups, examine the case and complete the following items:

- What are some of the critical issues in this case?

- Has Thomas engaged in sharing or cheating behavior?

- How should the professor respond to each student?

- How can Andrew be supported in his studies to ensure that he completes his own work and achieves the learning objectives for the course?

- Present your group’s findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Here is another case, adapted from a document entitled “Collaborating with Integrity” (McGowan, 2016, as cited in Contract Cheating and Assessment Design, n.d.a, p. 2).

Case Study: Collaboration or Cheating?

In pairs or small groups, examine the case and complete the following items:

- Does the work belong to Amara?

- Would it be worse if Amara had outsourced the whole assignment?

- Would it be worse if Amara had not paid money for the assignment?

- How can Amara be supported in her studies to ensure that she completes her own work and achieves the learning objectives for the course?

- Present your group’s findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

As this textbook section makes clear, plagiarism is a form of cheating. The following list, adapted from Penn State University (2017b, “Student Dialog – What is Plagiarism?”), identifies a number of cheating/plagiarizing behaviors.

- Submitting a paper you have not written as your own original work.

- Copying answers or text from another classmate and submitting them as your own.

- Quoting from another paper, book, journal article, newspaper article, magazine article, or website without using quotation marks and crediting the original author.

- Using long pieces of text or unique phrasings without using quotation marks or indenting the block of text and acknowledging the original source.

- Using data without crediting the original source.

- Proposing another author’s idea as if it were your own.

- Paraphrasing by simply replacing source language with synonyms while retaining the original author’s sentence structure and sequence of ideas.

- Paraphrasing by restating an original source’s ideas in your own words but failing to cite and reference the source.

- Fabricating references or using incorrect references.

- Submitting someone else’s computer program or spreadsheet with minor alterations as your own work.

- Using the same paper, project, or something you created previously in school for a current college course without permission.

These are cheating behaviors, according to information adapted from Penn State University (2017b, “Student Dialog – What is Cheating?,” “Student Dialog – What is Plagiarism?”), because they wrongly take credit for work produced by others. Academic cheating happens when students copy answers on exams or homework assignments; buy papers; arrange for other people to complete work on their behalf; obtain copies of exams, homework assignments, notes, or other academic work and use them as their own; or share assignments with other students with the result that the recipients submit the work as their own. Although this is not a definitive list, know that any action that takes credit for another’s work can be construed as plagiarism or cheating. However, things like studying in groups and copying a classmate’s notes from a lecture you missed are not necessarily acts of plagiarism or cheating. If you have any questions about whether working together and sharing notes is acceptable, ask your instructor. It is better to ask for clarification before you do something than to have to defend your actions later.

To draw this section to a close, plagiarism and cheating are wrong because they are behaviors that seek to gain advantage over others by deception. They have far-reaching consequences, according to information adapted from Penn State University (2017b, “Why Plagiarism and Cheating are Wrong”), which include loss of academic and professional reputation, receipt of failing grades, expulsion from college, withdrawal of diplomas, and damage to career prospects. These behaviors also disrespect peers who complete their own work and earn their grades fairly, cause others to question the reputation of a dishonest student’s educational institution, show disrespect for instructors who trust that students will complete their own work, and prevent deceitful students from learning and practicing skills they will likely need in their future careers.

Stanford University’s Office of Community Standards, Student Affairs (n.d.) lists sample plagiarism cases and accompanying sanctions for the cases. Read this information, which can be found at https://communitystandards.stanford.edu/policies-and-guidance/what-plagiarism/sample-plagiarism-cases, and work in pairs or small groups to complete the following items.

- Based on the information in this chapter, do you think the punishments are reasonable? Why or why not?

- Share your group’s ideas with the class.

How does a writer avoid plagiarism and its consequences?

Penn State University (2017a, “How You Can Avoid Situations that Lead to Academic Dishonesty”) recommends that students avoid situations that lead to academic dishonesty by doing the following:

- Be proactive. If you do not understand an assignment or are unclear about your instructor’s expectations, ask early in the semester.

- Plan ahead. Look at the workload for all your courses. When are your assignments due? How much work will each take? What can you start on right away?

- Know where to find information and resources, such as guidance on citation and referencing and university policies about academic integrity.

What can you add to this list? Work in pairs or small groups to brainstorm a checklist to help students avoid plagiarism. Refer to the guidance provided in the current chapter as needed when compiling the list.

Homework: Discuss Your Commitment to Academic Integrity in a Letter to Your Instructor

Write a block-formatted letter to your instructor in which you address the following question: How will you demonstrate that you have developed a personal commitment to academic integrity and professionalism? You may discuss the guidance provided in this chapter when writing your letter, but remember to cite and reference any outside sources of information you use. Consult the “Organizing Paragraphs” and “Writing Print Correspondence” chapters of this textbook for help when writing and formatting your letter.

Once you have drafted your letter, use the following handout (McKeever, n.d.) to edit and proofread your work.

Editing and Proofreading Strategies

Editing is the correction of mechanical errors like grammar, punctuation, and spelling; and of mistakes such as omitted or repeated words and typing errors. When you proofread you double-check that all these errors, as well as spacing and formatting problems, have been corrected. In the writing process, editing and proofreading come last, after revising. When you proofread, you are not just looking for errors in this paper; you are also identifying your bad habits to avoid them in future writing.

To catch spelling or word choice errors, read each word individually from the end of each line to the beginning. Computer spell checkers won’t catch sound-alikes such as they’re, their, and there, or errors such as typing he for the. (Spell checkers are interactive–you have to choose the right word each time it stops. There’s no getting around it—you have to learn the difference between words like were and where. A grammar handbook or dictionary can help.)

References

Contract Cheating and Assessment Design. (n.d.a). Collaborating with integrity. License: CC-BY-NC-SA. https://cheatingandassessment.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/STUDENT-RESOURCE-Collaborating-with-integrity.pdf

Contract Cheating and Assessment Design. (n.d.b). Scenario resource: Sharing or cheating? License: CC-BY-NC-SA. https://cheatingandassessment.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Scenario_sharing-or-cheating.pdf

ICAI. (2013). The fundamental values of academic integrity (2nd ed.). (T. Fishman, Ed.). https://www.academicintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Fundamental-Values-2014.pdf

ICAI. (2017). Fundamental values of academic integrity. https://www.academicintegrity.org/fundamental-values/

Indian River State College (IRSC) Libraries. (2019, March 25). Paraphrasing and quoting 101 APA style [Infographic]. License CC-BY-NC-SA. https://irsc.libguides.com/apa/paraphrase

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Defining plagiarism. In English composition. License: CC-BY-SA. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/cochiseeng101/chapter/defining-plagiarism/

McKeever, R. (n.d.). Editing and proofreading strategies. Yuba College Writing & Language Development Center. License CC-BY-NC..https://yc.yccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/EditingProofingAccessibleMarch2019.pdf

Office of Community Standards, Student Affairs. (n.d.). Sample plagiarism cases. Stanford University. https://communitystandards.stanford.edu/policies-and-guidance/what-plagiarism/sample-plagiarism-cases

Penn State University. (2017a, August 8). iStudy for success!: Excuses and penalties. License: CC-BY-NC-SA. http://tutorials.istudy.psu.edu/academicintegrity/academicintegrity7.html

Penn State University. (2017b, August 8). iStudy for success!: Plagiarism and cheating. License: CC-BY-NC-SA. http://tutorials.istudy.psu.edu/academicintegrity/academicintegrity3.html

Turnitin. (2016). The plagiarism spectrum [Infographic]. https://www.turnitin.com/static/plagiarism-spectrum/