Delivering Presentations

Stacey Corbitt

Chapter Overview

Understanding the anxiety that accompanies public speaking is an effort you might make in an introductory psychology class, but the subject is beyond the scope of this textbook. The good news is that, contrary to how you might feel as a college student, delivering a presentation is not likely to be an activity that will lead to your demise. In fact, you probably engage in behaviors nearly every day that are much more risky than speaking in front of an audience.

Nevertheless, this chapter aims to help you select information to address; develop visual media; prepare and practice remarks; and deliver a successful presentation, all while practicing calm composure. Because writing and delivering presentations are not discrete steps but are, like most other technical communications, interconnected activities, you will not find separate processes discussed in this chapter. Instead, think of the whole experience as a singular activity: that is, perhaps, doing presentations as a means of offering technical information for use by a broad audience.

A number of accessible resources exist to help people of varying skill and experience levels overcome the nervousness surrounding all aspects of presentations. This chapter, however, focuses specifically on the unique challenges scientists and engineers – both students and professionals – encounter when writing about and presenting technical information. The following discussion is adapted from a blog post by TED Writer Kate Togorvnick May (2012), in which the author highlights “six specific strategies that scientists and engineers can use while preparing to share their work outside their field” as presented by Penn State University instructor Melissa Marshall in Marshall’s 2012 TED Talk exploring the subject of developing and delivering technical presentations to a non-specialized audience.

Strategy 1: analyze the audience

Marshall advises writers to begin by assuming the audience for a presentation is interested in learning about the research, even if they do not have the same scientific or technical background. In other words, your audience cares about the information you are presenting. Starting from that point, she says this about the idea that scientific information should be “dumbed down”:

I think this is a flawed perspective that doesn’t place enough emphasis on the responsibility of the speaker to communicate clearly. As speakers, we have to respect our audience — we need them on our side! You can clearly communicate your science without compromising the ideas (as cited in May, 2012).

Understanding the background and interests of the audience allows you to adapt your material and your delivery to meet their needs.

Think about a time when you were an audience member for a presentation of new or unfamiliar material. The situation may have been a recent experience during a class or seminar. How did the speaker demonstrate his or her responsibility for ensuring their communication was clear? How did the speaker express respect for his or her audience? Could you identify instances in which the speaker “dumbed down” the science in their presentation? If so, what was the effect of that approach on your experience?

In the space provided below, respond to these prompts and be prepared to discuss your responses in class.

Strategy 2: acknowledge the audience

As a student, you are certainly aware of the difficulty audience members face when the material being presented is not clearly relevant to the audience’s needs or interests. As a speaker, you are responsible for making the information you present understandable and engaging for the audience. When you take Marshall’s advice (as cited in May, 2012) and make an early effort to explain why your presentation should matter to them, that action “creates an instant connection between you and the audience because the audience perceives you as being invested in their understanding of the talk.”

Think about a time when you were tasked with teaching someone information he/she did not want to learn, or at least something in which the audience had little or no interest. Some teachers have such experiences often, but what about you? Discuss your experience with a partner in class using the following questions to guide your discussion:

- What was your purpose in presenting the information?

- Who was your audience?

- How did you know the audience was not engaged with you or your presentation?

- What (if anything) could you have done to improve the situation?

As you discuss your experiences with a disinterested audience, keep in mind that the last question, What (if anything) could you have done…? is intended to encourage you to think about the problem in a new way. Again, recognize that you are responsible for making the information you present understandable and engaging for the audience, so blaming the audience for their lack of attention doesn’t work. Instead, think of ways you can acknowledge the audience in terms of what benefits they can derive from engaging with your talk and your message. The unspoken question from every audience is “What’s in it for me?”

Activity: practice scenario

Consider the scenario below, respond to the prompts, and be prepared to discuss your notes.

You are a safety professional charged with delivering a presentation at the beginning of a community clean-up project. Your audience is a group of teens ranging in age from 14 to 18 years old who are required to volunteer by a court order to provide community service. Your purpose is ensuring the teens understand and adhere to the job’s safety requirements.

Following the advice described above, analyze your expected audience. How will you take responsibility for ensuring your message is clear? How will you show respect to the needs of your audience? In the space provided below, respond to these prompts and be prepared to discuss your responses in class.

Next, acknowledge that your audience may not clearly understand how your presentation relates to them. How might you address the unspoken question from your audience: What’s in it for me?

Strategy 3: relate the information to the audience

Kate May’s summary of this point indicates that you must explain how your presentation is relevant to the audience, perhaps by using examples or telling a story that interests and resonates with them. She offered the following suggestion:

[A]nalogies are one of the most powerful speech strategies available to a presenter of science as they anchor a complex technical idea to a concept that the audience already understands. When you use an analogy, you are using the audience’s prior knowledge to explain your concept (May, 2012).

Consider the Facebook post about climate change penned by former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. First, determine as a group who you think was the intended audience for the post. Next, what was Schwarzenegger’s purpose in posting the writing? Make notes below for use in your discussion.

Note in particular his analogy that compares two doors to the choice between fossil fuels and renewable sources of energy. Discuss the author’s use of analogy, considering Kate May’s direction that analogies should “anchor a complex technical idea to a concept that the audience already understands.” Do you think this example accomplishes what May suggested? Be prepared to discuss your answer.

In class, discuss the idea of using analogies to help an unfamiliar party understand information that makes sense to you and others learning or working in your field. Working with a partner or as directed by your instructor, describe a specific concept or significant point relevant to your field and/or your research for this class. Use the space provided on this page and be prepared to discuss your response in class.

Your example provided in response to this prompt might lend itself to the use of an analogy that could help unfamiliar audience members understand the basic concepts you want them to grasp. Can you think of a possible analogy you might use when presenting the concept to an unfamiliar audience?

Strategy 4: do the math for the audience

As a presenter, you must know the level of understanding your audience has about your topic in order to set a context that will help them use the material you are presenting. In some cases, setting an appropriate context means you must “do the math” for the audience in ways such as

- presenting material like experimental results on slides using a series of steps and explaining each part before progressing to the next step/slide

- using illustrations, rather than text, as the main content for slides

- simplifying charts and graphs to highlight specific points

- doing the actual math by presenting calculations step-by-step using slides that mirror your discussion

However you opt to help your audience access your presentation by doing the math for them, remember that less is more with slides or other visual aids. As Aaron Weyenberg, TED’s “master of slide decks” explains:

The presentation needs to stand on its own; the slides are just something you layer over it to enhance the listener experience. Too often, I see slide decks that feel more like presenter notes, but I think it’s far more effective when the slides are for the audience to give them a visual experience that adds to the words (TED, 2014).

Activity: analyze a bad example

Work with a partner in class (or as otherwise directed by your instructor) to search for an example of what you consider to be a poorly-constructed or otherwise ineffective slide. Alternatively, use Microsoft PowerPoint or another approved software application and create your own terrible slide. Prepare remarks to present during class to demonstrate the errors you identified in your example.

Strategy 5: don’t shoot the audience

Technical writers have a variety of tools and techniques available to aid in making documents effective. Among those tools are elements like illustrations, section headings, numbered lists, outlines, and bullet points. In her TED Talk linked earlier in this chapter, Melissa Marshall (2012) focused particular attention on one of the technical writer’s popular tools: “[When] presenting your work, drop the bullet points. Have you ever wondered why they’re called bullet points? What do bullets do? Bullets kill, and they will kill your presentation” (Marshall, 2012).

Marshall continued by offering two example slides, saying “A slide like this is not only boring, but it relies too much on the language area of our brain, and causes us to become overwhelmed.” Below is an image of the slide she was talking about.

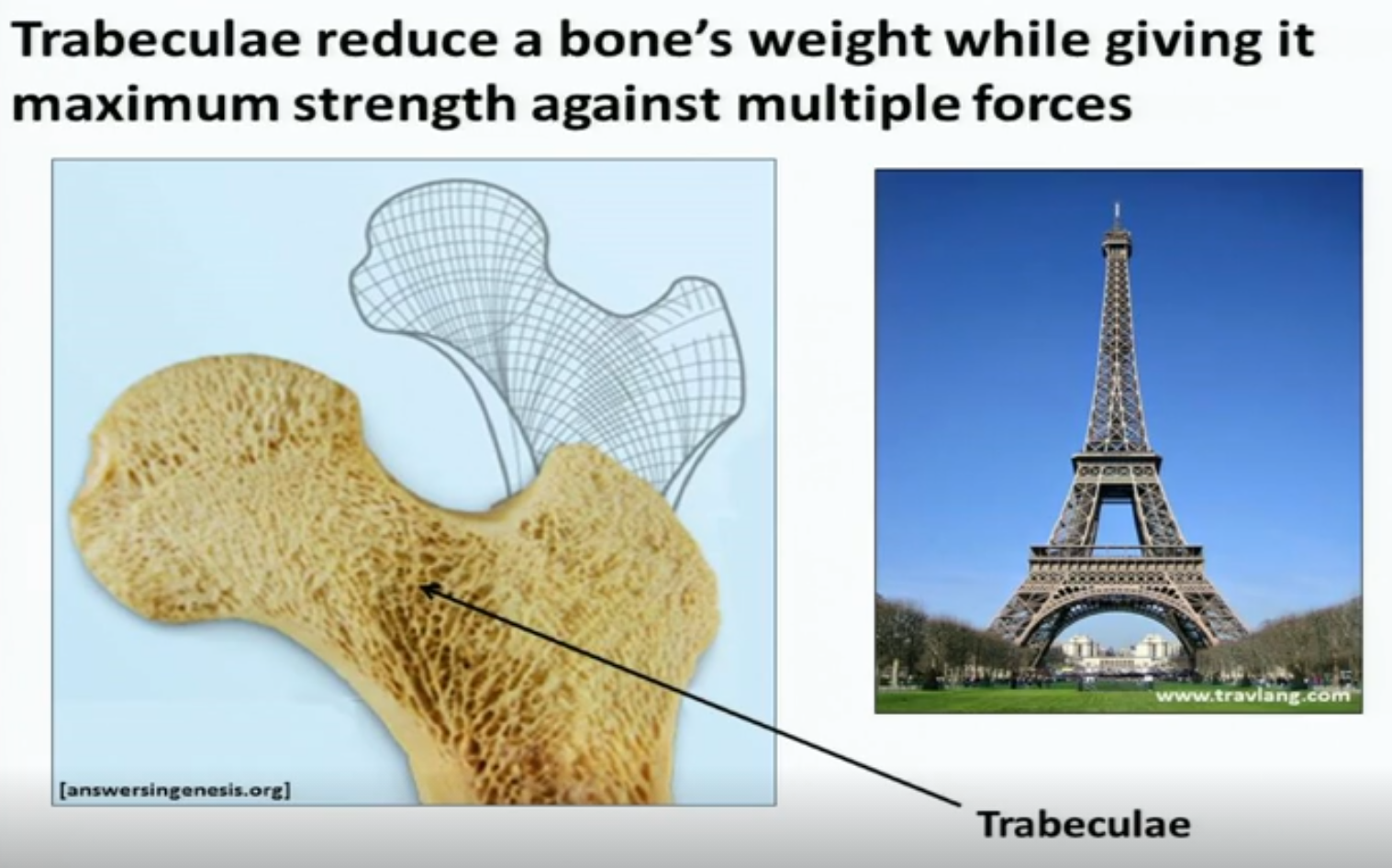

Marshall then demonstrated a better alternative slide design: “Instead, this example slide by Genevieve Brown is much more effective. It’s showing that the special structure of trabeculae are so strong that they actually inspired the unique design of the Eiffel Tower.”

Strategy 6: engage with the audience

Think about the best, most engaging presentation you have seen in recent years. As an audience member, what did you find engaging or exciting about that presentation? In other words, what made the presentation – and the presenter – the best?

It is possible your response to the prompt above indicates that you admired or enjoyed some characteristics of the presenter, and the information you received was less notable. It may be that the best presenters appear trustworthy, and genuine, and reliable in part because they display confidence in themselves as well as in the information they present.

Where do great presenters get their confidence?

As a student of technical writing, you know the single most important element of study to your success is practice developing documents that are clear, concise, complete, and correct. A presentation is a form of technical communication much like a document: and the only path to mastery of writing and delivering presentations is practice.

Think about the presence of practice in your own life, and discuss your ideas in class. What have you learned personally about practice? How did you learn the lesson(s) you’ve learned about practice? When practice leads to mastery of a skill, what additional benefits do you receive?

Chapter conclusion

Presenting technical information is probably the topic of a full-term length course in your science or engineering curriculum. Nevertheless, you should expect to be called upon to write and deliver presentations in classes or on the job before you have completed that course. This chapter provides an introduction to presentations, focusing specifically on the unique challenges scientists and engineers – both students and professionals – encounter when writing about and presenting technical information. Your review, discussion, and reflection throughout your study of this chapter should help you select information to address; develop visual media; prepare and practice remarks; and deliver a successful presentation. Refer to all of the six strategies that work together to help you practice and develop confidence as a presenter.

Homework

Write a memo to your instructor that outlines your proposed plan for a safety orientation presentation.

- Your audience and purpose for the presentation are identified in the first Activity in this chapter (teens participating in a community cleanup).

- Address the memo to your instructor and identify yourself as the safety professional in charge of orientation.

- Using your notes from the Activity as a starting point, explain how you will employ the six strategies discussed in this chapter to ensure a successful presentation.

References

Marshall, M. (2012, October). Talk nerdy to me [Video]. TED Conferences. License: CC BY–NC–ND 4.0. https://www.ted.com/talks/melissa_marshall_talk_nerdy_to_me

May, K. T. (2012, October 11). 6 speaking tips for scientists and engineers. TEDBlog. License: CC BY–NC–ND 4.0. https://blog.ted.com/6-tips-on-how-scientists-and-engineers-can-excite-rather-than-bore-an-audience/

Schwarzenegger, A. (2015, December 7). I don’t give a **** if we agree about climate change. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/notes/arnold-schwarzenegger/i-dont-give-a-if-we-agree-about-climate-change/10153855713574658

TED Staff (2014, July 15). 10 tips on how to make slides that communicate your idea, from TED’s in-house expert. TEDBlog. License: CC BY–NC–ND 4.0. https://blog.ted.com/10-tips-for-better-slide-decks/