Introducing Technical Writing

Dawn Atkinson and Sarah Raymond

Chapter Overview

This chapter aims to help you understand what technical writing is, what it is used for, and what characteristics and conventions help to define it.

A Definition of Technical Writing

Although you may not yet be fully familiar with the characteristics of technical writing, you have likely experienced technical writing at one time or another in your daily life as a student, employee, or consumer. Technical writing, according to this book’s definition, aims to help individuals perform workplace tasks, carry out a series of operations, understand concepts or research, solve problems, operate technology, or communicate in a professional manner. You may have encountered technical writing in textbooks, operations manuals, company policies, or illustrations in magazine articles. To extend our definition of technical writing, textbook author Last (2019, p. 6) explains that this form of non-fiction writing communicates information for practical and specific purposes, takes document design into account, and is usually intended for particular readers.

The Characteristics of Technical Writing

When we employ technical writing, we strive to keep readers in mind and tailor our communication for a particular purpose. The audience for a piece of technical writing is the individuals who will read the text. Since technical writing may be used in multimedia documents, such as presentations, videos, and podcasts, an audience might also include listeners, viewers, and users. The purpose for a piece of technical writing signifies the reason it has been produced. In general, the purpose for a piece of communication is either to entertain, sell, inform, or persuade; however, documents may also address more than one of these purposes. Technical writing, in comparison, may be produced with more specific purposes in mind, such as to provide or ask for information, record details, or convince readers of something (Last & Neveu, 2019, p. 18). Again, technical documents may also reflect more than one of these purposes.

Seven attributes help to define technical writing and ensure that it adequately addresses audience and purpose. Specifically, technical writing is clear, coherent, concise, concrete, correct, complete, and courteous. The following definitions of these characteristics are adapted from Last (2019, pp. 43-44).

Clear writing communicates a writer’s ideas and purpose in a straightforward manner. It targets a particular audience by being precise and moderating technical words, obscure phrases, and jargon, specialized language or terminology used in a particular field of study or workplace environment. It also foregrounds important information for the benefit of readers and conveys one main idea per paragraph.

Coherent writing builds links between ideas so readers can easily follow them. One idea should lead logically into the next via use of transitional words and phrases, intentional repetition, sentences with clear subjects, specific and informative titles and headings, parallel lists, and consistent document design. When writing is coherent, readers can easily track thoughts and lines of reasoning; incoherent writing, in comparison, is choppy and hard to follow since its ideas appear to be disconnected or incomplete.

Concise writing is efficient: it delivers its message clearly without using extraneous words that slow readers. To produce concise writing, avoid unnecessary padding in sentences, awkward phrasing, overuse of be verbs (is, are, was, were, am, be, being, been), long preposition strings, vague language (words like good, bad, and do), unnecessary repetition, and redundancy. In addition, use active verbs whenever possible, and take the time to select a single, expressive word rather than using a long or clichéd phrase. Think of your word count like a budget; be frugal by making sure every word you choose works hard to communicate meaning.

Concrete writing uses specific, exact language so readers can easily understand points. If you have to explain an abstract concept, use familiar examples, everyday comparisons, and precise language. In addition, use measurable or specific descriptors whenever possible instead of words that encompass a range of interpretations (e.g., big, little, very, extremely, and great).

Correct writing uses conventional English punctuation, capitalization, grammar, and sentence structures; provides accurate information that is communicated in an ethical way; and employs the right document type for the task.

Complete writing includes all requested information and answers all relevant questions. Carefully read and follow specifications to ensure your documents are complete.

Courteous writing employs an intuitive design that is easy to scan; uses respectful language; addresses readers appropriately; and avoids potentially offensive terms and tone.

Writing that is clear, coherent, concise, concrete, correct, complete, and courteous establishes credibility with readers, demonstrates dedication and care, and communicates messages convincingly.

The Conventions of Technical Writing

Documents typically follow conventions, expectations about key features that affect how they are organized, designed, and written. Conventions help readers recognize and categorize documents into genres, or types of writing; conventions also help writers to produce texts in line with accepted standards.

Certain conventions typify technical writing as a means for communicating information clearly and effectively to people who need it. Table 1 provides an overview of these conventions.

| Considerations | Conventions |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Communicates technical and specialized information in a clear, accessible, and useable manner to people who need it to perform workplace tasks, carry out a series of operations, understand concepts, solve problems, operate technology, or communicate in a professional manner |

| Audience | Addresses various audiences: e.g., employees, managers, executives, clients, the general public, funding bodies, students, and entities with legal authority |

| Writing Style | Uses concise, clear, plain, and direct language that is formal or moderately formal; may include specialized terminology; typically incorporates short sentences written in the active voice; and makes purpose immediately clear |

| Tone | Maintains a tone that is courteous, constructive, and professional |

| Structure | Uses concise paragraphs, clear transitions, and structural cues (e.g., informative headings and titles) to organize and forecast content for readers |

| Format/Design | Includes electronic, visual, and printed documents of different lengths (e.g., long reports and short emails, letters, and memos); incorporates headings, lists, figures, and tables |

| Other Features | Focuses on data-driven ideas and evidence |

The conventions outlined in Table 1 help make technical writing easy-to-navigate and reader focused.

Activity A: Identify the Audiences for Pieces of Technical Writing

Read the extract.

An extract from the article “Remote Reefs and Seamounts are the Last Refuges for Marine Predators across the Indo-Pacific” (Letessier et al., 2019, “Abstract”)

What can you tell about the intended audience for the text?

Read another example of technical writing.

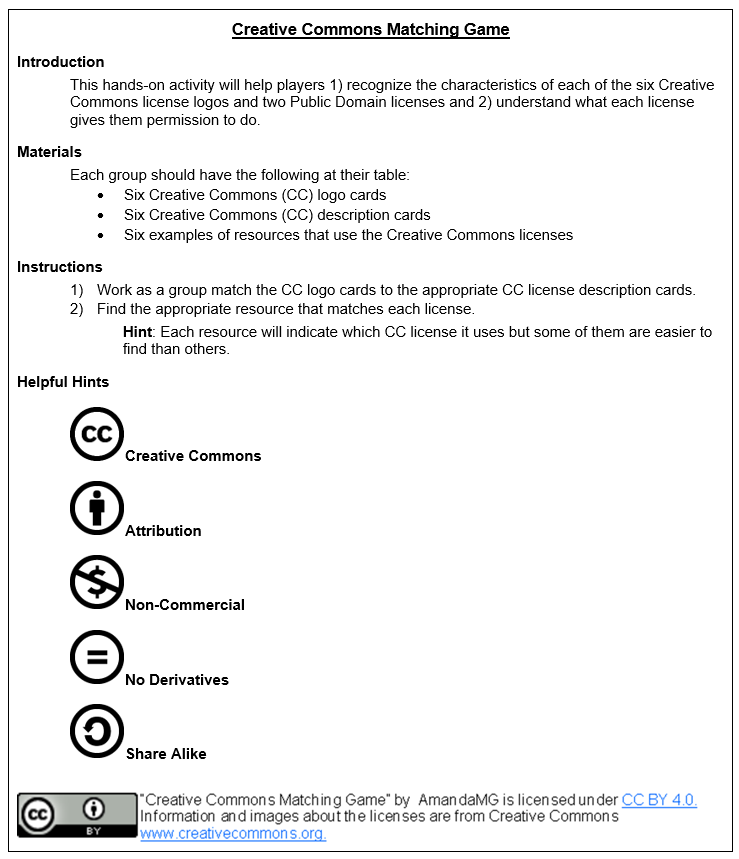

A set of instructions for a Creative Commons game adapted from Northwest Vista College Library

Figure 2: “Creative Commons Matching Game” by AmandaMG is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Information and images about the licenses are from Creative Commons.

What can you tell about the intended audience for this document?

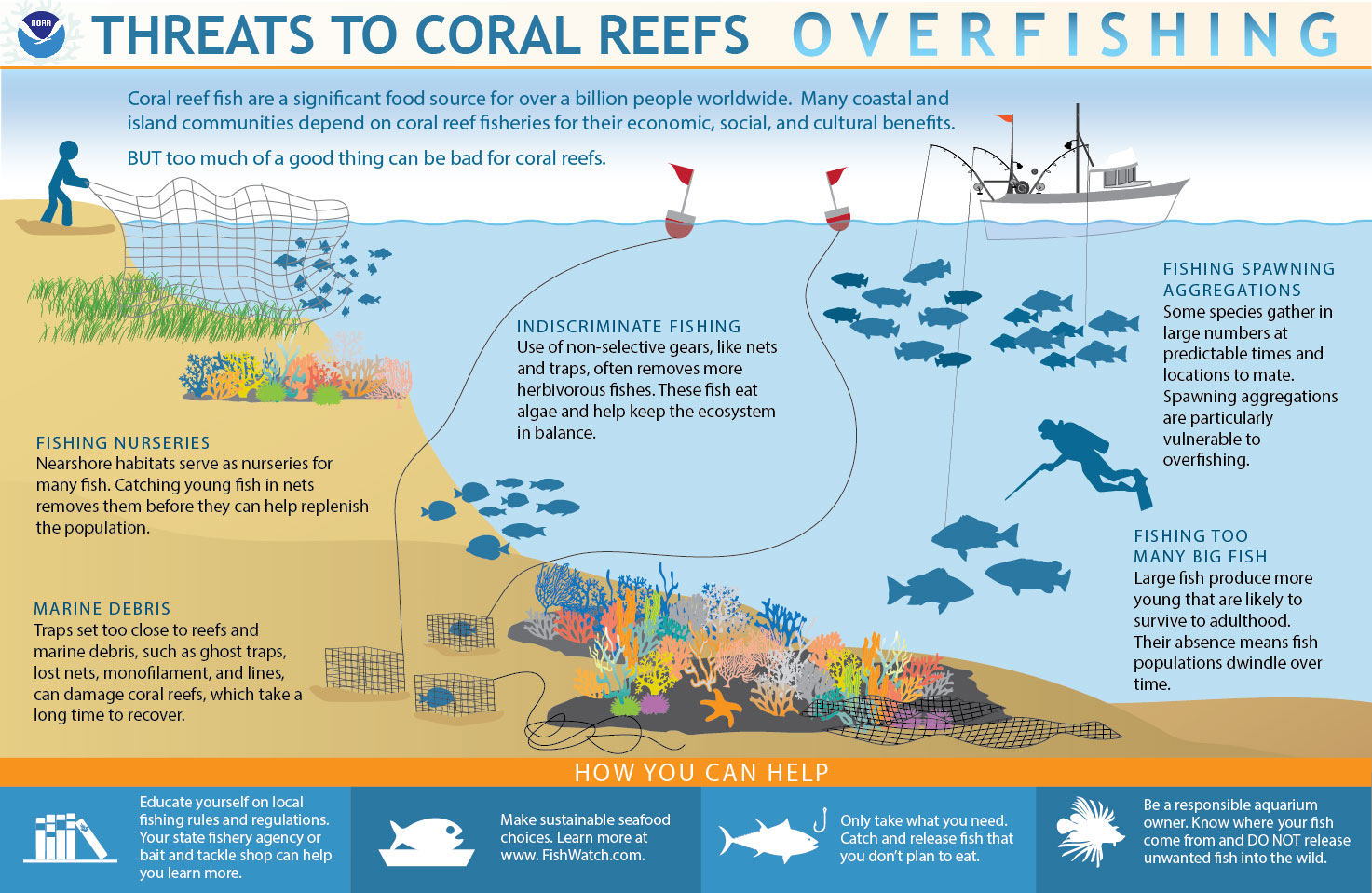

Now read a third example of technical writing in Figure 3. Infographics combine text, visuals, and numbers to communicate dense information in quick and easy-to-read formats.

An infographic focusing on how overfishing affects coral reefs (NOAA, 2018)

What can you tell about the intended audience for this document?

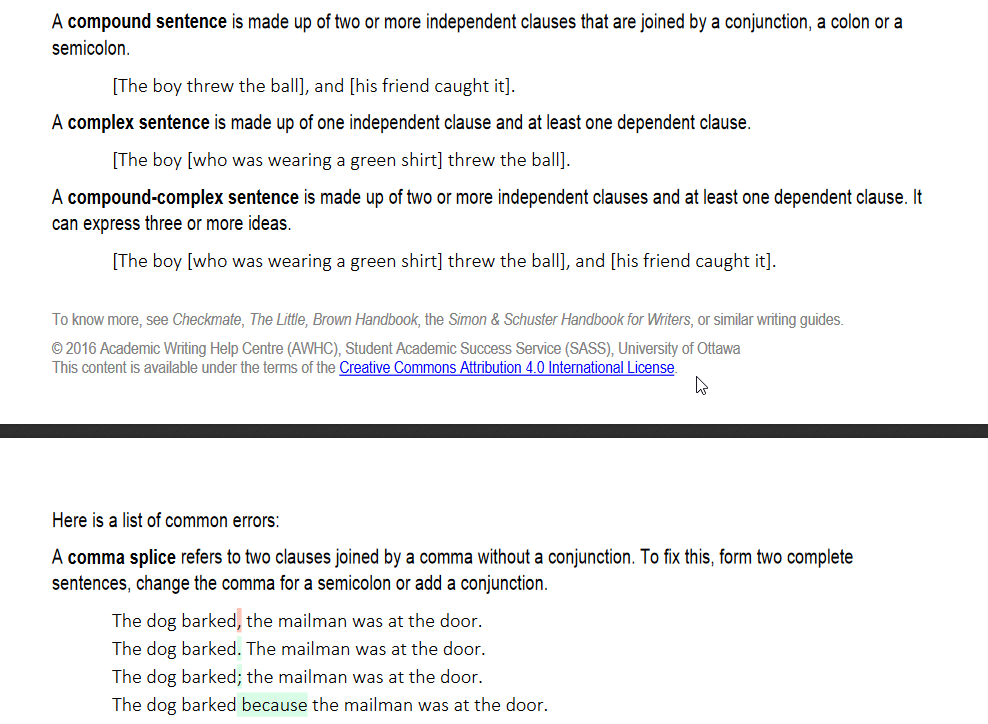

Lastly, read the document in Figure 4.

Comparative Essays

Writing a comparison usually requires that you assess the similarities and differences between two or more theories, procedures, or processes. You explain to your reader what insights can be gained from the comparison, or judge whether one thing is better than another according to established criteria.

Helpful tip: When you are asked to write a comparative essay, remember that, unless you are instructed otherwise, you are usually being asked to assess both similarities and differences. Such essays may be called comparative essays, comparison essays, or compare-and-contrast essays.

How to write a comparative essay

- Establish a basis of comparison

A basis of comparison represents the main idea, category, or theme you will investigate. You will have to do some preliminary reading, likely using your course materials, to get an idea of what kind of criteria you will use to assess whatever you are comparing. A basis of comparison must apply to all items you are comparing, but the details will be different.

For example, if you are asked to “compare neoclassical architecture and gothic architecture,” you could compare the influence of social context on the two styles. - Gather the details of whatever you are comparing

Once you have decided what theme or idea you are investigating, you will need to gather details of whatever you are comparing, especially in terms of similarities and differences. Doing so allows you to see which criteria you should use in your comparison, if not specified by your professor or instructor.

e.g.

| Criteria | Neoclassical Architecture | Gothic Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Churches | Appeal to Greek perfection | Appeal to emotion |

| Civic buildings | Columns | Towers and spires |

| Palaces | Formulaic and mathematical | Wild and rustic |

Helpful tip: Organize your criteria in columns or a Venn diagram; using visual methods to map your pre-writing work can help you to stay on track and more clearly get a sense of how the essay will be structured.

Based on the information in the above table, you could focus on how ornamentation and design principles reveal prevailing intellectual thought about architecture in the respective eras and societies.

- Develop a thesis statement

After brainstorming, try to develop a thesis statement that identifies the results of your comparison. Here is an example of a fairly common thesis statement structure:

e.g., Although neoclassical architecture and gothic architecture have [similar characteristics A and B], they reveal profound differences in their interpretation of [C, D, and E].

Helpful tip: Avoid a thesis statement that simply states your obvious purpose.

e.g., The aim of this essay is to compare [A and B] with reference to [X, Y, and Z].

- Organize your comparison

You have a choice of two basic methods for organizing a comparative essay: the point-by-point method or the block method.

The point-by-point method examines one aspect of comparison in each paragraph and usually alternates back and forth between the two objects, texts, or ideas being compared. This method allows you to emphasize points of similarity and of difference as you proceed.

In the block method, however, you say everything you need to say about one thing, then do the same thing with the other. This method works best if you want readers to understand and agree with the advantages of something you are proposing, such as introducing a new process or theory by showing how it compares to something more traditional.

Sample outlines for comparative essays on neoclassical and gothic architecture

Building a point-by-point essay

Using the point-by-point method in a comparative essay allows you to draw direct comparisons and produce a more tightly integrated essay.

Helpful tip: Note that you can have more than three points of comparison, especially in longer essays. The points can be either similarities or differences. Overall, in order to use this method, you must be able to apply criteria to every item, text, or idea you are comparing.

- Introduction

- Introductory material

- Thesis: Although neoclassical and gothic architecture are both western European forms that are exemplified in civic buildings and churches, they nonetheless reveal, through different structural design and ornamentation, the different intellectual principles of the two societies that created them.

- Body section/Paragraph 1: Criterion A (Ornamentation)

- Text 1

- Text 2

- Body section/Paragraph 2: Criterion B (Major appeal)

- Text 1

- Text 2

- Body section/Paragraph 3: Criterion C (Style)

- Text 1

- Text 2

- Conclusion

- Summary

- Why this comparison is important and what it tells readers

Building a block method essay

Using the block method in a comparative essay can help ensure that the ideas in the second block build upon or extend ideas presented in the first block. It works well if you have three or more major areas of comparison instead of two (for example, if you added in a third or fourth style of architecture, the block method would be easier to organize).

- Introduction

- Introductory material

- Thesis: The neoclassical style of architecture was a conscious rejection of the gothic style that had dominated in France at the end of the middle ages; it represented a desire to return to the classical ideals of Greece and Rome.

- Body

- Text 1: History and development

- Text 2: Change from earlier form; social context of new form

- Synthesis and analysis: What does the comparison reveal about architectural development?

- Conclusion

- Summary

- Why this comparison is important and what it tells readers

What can you tell about the intended audience for this document?

How do the audiences for the four examples you looked at differ? How might these differences have shape the documents’ development? Please be prepared to discuss your ideas in class.

Activity B: Consider the Implications of Integrity in the Workplace

As this chapter mentions, correct technical communication is truthful in its message and is communicated ethically. To explore what these concepts mean from various perspectives, read the following piece, composed by Sarah Raymond, Director of Career Services at Montana Technological University. In 2020, Ms. Raymond conducted a series of informational interviews with employers to discover what integrity means to them. After you have read the text, work with classmates to address the questions that follow. Be prepared to discuss your team’s responses in class.

What do you do when no one is watching?

Although integrity, by definition, is “the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles” (Lexico, 2020, definition one), it is one of those abstract personal traits that can be difficult to pin down. Regardless, most people know what it is when they see it. You have probably witnessed times when people have disregarded integrity and may or may not have been caught. It can be devastating to watch when someone does get exposed, either as a result of a serious infraction or several small infractions that have previously been overlooked. In either case, the repercussions can be great.

Integrity is certainly important in academics, as academia is a training ground for the workplace. During her interview, Koren Vining, Vice President and Branch Manager at Cetera Investors, concurred with this view: “College gives you time to practice integrity and hone those skills, [and]…if you screw up, it isn’t life altering.” Mistakes can, in fact, help people learn. Vining said she hopes her children learn from their mistakes before they enter employment—before their actions can really hurt their lives. To be sure, lapses in judgement, integrity, and ethical decision making can lead to substantial costs in the workplace (for example, your job, your money, your time, other people’s time, and other people’s money).

Companies recognize integrity in their employees and tend to promote those who work hard, do a good job, and have impeccable behavior. What leaders do and how they behave matters because people are always watching. Quality leadership correlates with a high degree of integrity (as well as transparency, accountability, responsibility, self-awareness, and other traits). Vining explained,

There comes a time when you are ready to take the next step; by having worked the right way, you have put in the effort, you have practiced the skills for future success. If you have been accidentally successful, there will come a time when it will crash.

Working in an investment firm, Vining has unfortunately seen this destructive situation happen to former employees. In a highly regulated business, someone is always watching.

As a testament to her integrity as a leader, Vining has shared pieces of her management style and has been open with members of her work team. This transparency allows her team members to be successful on their own terms. To encourage their success and self-sufficiency, Vining shares the following guidance with her team members:

Do your work. If you need a boss, someone to stand over you, this isn’t going to be a successful working relationship. However, if you need some structure and a coach, you can dictate your own success. Are you working on your own plan, or are you working on a plan that belongs to someone else?

Vining clearly values her employees’ beliefs in their ability to be successful and is transparent in her expectations.

In today’s new abnormal, remote work is something many people have experienced for a sustained period of time. Maybe you have even experienced a remote classroom that was not what you had planned when you registered for the term. In this type of situation, discipline and focus will serve you well as opposed to trying to avoid hard work by taking short cuts. In relation to this point, Vining asked, “How do you want people to think about you?” In other words, what do they say about you when you are not there? Your personal brand and what you stand for matter in the workplace.

Putting in extra effort and time on tasks can cause stress, but Vining shared an alternate view: “Unless you are really a crappy person, there is stress involved with taking the short-cut too.” In other words, taking short cuts to circumvent hard work is stressful because of the fear of getting caught.

Vining offered sage advice as a 19-year recruiting veteran: “Cultivate personal integrity. You will be more apt to have more success.” At the companies she has worked, she has been fortunate to witness corporate America elevate people who have integrity. And, conversely, she has seen those who do not demonstrate integrity suffer. “Eventually it comes out, it may be post-mortem and that is certainly not how you want to be remembered.” When you are responsible for someone else’s resources (money, time, property) in a job, people expect you to value that position. Employers trust you to make the next right decision.

According to Glen Fowler, the former President of Mountain Pacific Association of Colleges and Employers (MPACE) and the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), the adjectives integrity and credibility are synonymous. “Everything you say, if you are credible, I believe you without question. It is a distraction if you have to spend time and second guess people.” Credibility is something that most employers are able to identify early in someone’s career. Similarly, lack of credibility on the job—for example, when steering a team or when reporting back on its work—can be career limiting. “Credibility is about your personal reputation. Once it is marred, it is all over,” according to Fowler. “People underestimate how small the world is. Leadership or decision makers know each other and if not, they will reach out to someone.” Again, integrity is central to effective workplace performance.

Fowler echoed that academia is the time to develop and hone behavioral integrity. “This is how you are going to conduct yourself in the future.” During his professional career, while onboarding staff and hiring scores of people, he observed that individuals entering his industry were Type A personalities. “These [were] people who [were] used to having all the answers. We had to break them of that mentality, break the conditioning they had developed. We had to give them the license to say ‘I don’t know.’” Fowler stressed, “You are better off saying that you don’t know. You are hired for your expertise, but if you start your response with a conditional statement, ‘I think,’ people don’t hear that qualification.” Fowler also emphasized, “A sign of maturity is to admit you don’t have all the answers,” and quickly added, “But you can get them!”

Another subtlety of integrity and a way in which people can get into trouble, according to Fowler, “Is not just what you share, but what you didn’t share even when you knew it would help and yet still withheld it.” People may not openly communicate for a variety of reasons, none of which may be malicious or self-serving. Maybe they do not communicate because they want to avoid confrontation or uncomfortable situations. Or, they may tell themselves it is not their place to be forthright. Regardless, “A junior-level person can question or stand up to a senior person, based upon perceived facts and still be respected,” according to Fowler. “To become a true leader, it is important to be engaged with your career and know yourself.” In other words, recognize and own the values that underlay your actions and behaviors.

Employers use job interviews to assess a number of things: for example, skills, past performance, technical expertise, and level of workplace integrity. Some recruiters use behavioral or situational questions to help them better understand how job applicants would handle real-life problems or common situations. Here are a few interview questions for you to consider. How would you answer them during an employment interview?

- Tell me about a time you were new to a company or work group. What steps did you take to build trust with co-workers and/or staff?

- Give an example of a time when you over-committed yourself. How did you handle it?

- Describe a situation when you worked with someone you did not like or respect. How did you cope with the relationship?

- Tell me about a time when your values were in conflict with your employment organization’s values. What did you do?

- Describe what the terms integrity and ethics mean to you. Tell me about a time when your integrity or ethics were challenged. What did you do?

Employers likely will not tell you outright when you are being asked questions about ethics or integrity. They may be more subtle and lay out situations to uncover your core values. Fowler shared, “Employers ask questions in…clever ways. They…[will] tee up a scenario that is specific to their industry. It gets at the heart of your personal judgement, conflict resolution, or teamwork.” How will you respond? Will you make the next right decision? Are you a match for the team they already have in place?

As an employee, you will be evaluated on the quality of work you produce. That is another way your employer will measure your credibility. Are you performing the responsibilities of your post with integrity? Your employer will trust that you are going to do your work correctly, produce credible deliverables, and communicate effectively throughout projects. Your employer, in short, will rely on you to do what you say you will do in order to uphold the organization’s reputation and your own.

Integrity is clearly more than just the definition of honesty and moral uprightness. Ultimately, all you have is your word. The ability to follow through on your promises contributes to your professional reputation, and relationships and interactions with others count for a great deal. If people are not able to trust or rely on you in the workplace, you will miss opportunities for personal and professional success. Barb Crump, Director of Human Resources at Northern Montana Hospital, deals with people every day in her role. She values fairness in the workplace, and people come to her because they rely on her expertise and trust her willingness to guide them correctly. Crump shared, “Recently there was a post on Facebook that sums up what we are discussing: ‘I no longer listen to what people say. I watch what they do. Behavior doesn’t lie.’”

What are your responses to these items?

- A new employee received training from someone else in the office. The person responsible for the training withheld information that was critical to completing a particular task. The new employee struggled to complete the task, and the trainer eventually shared the proper information.

-

- How might the new employee feel?

- Why would the person conducting the training withhold information?

- What was wasted during the process: time, money, opportunities for collaboration and peer-to-peer learning, mental energy, or something else?

- What might happen to team morale? What might happen to the overall morale in the office?

- What did the company lose?

- An employer contacted a university’s career services office to inquire about an intern’s transcript. The employer had worked with this office for some time to offer internship opportunities to students. The intern was required to provide the transcript as a condition of employment, but the employer had concerns about the document since its format did not resemble transcripts that had been provided in the past.

-

- What do you think might have happened with the transcript?

- What was damaged in this situation?

- How should the employer respond?

- How should the career services office respond?

- How should the university respond?

- Imagine you had the opportunity to interview for a dream job in your field and were provided the list of interview questions in advance. How would you respond to these questions?

-

- Tell me about a time you were new to a group. What steps did you take to build trust with its members?

- Give an example of a time when you over-committed yourself. How did you handle it?

- Describe a situation when you worked with someone you did not like or respect. How did you cope with the relationship?

- Tell me about a time when you encountered a conflict with someone, either at work or in school. What communication strategies did you use to resolve it?

Describe what the terms integrity and ethics mean to you. Tell me about a time when your integrity or ethics were challenged. What did you do?

Homework: Email Your Instructor about Your Experiences with Technical Writing

Consider this textbook chapter in relationship to your experience as a student, employee, or consumer. Compose an email to your instructor in which you address the following prompt: What are two kinds of documents you have written or encountered that could be characterized as technical writing, and why? Use standard conventions for professional emails when completing this task. For help with composing and formatting your email, consult the “Writing Electronic Correspondence” chapter of this textbook. This exercise is adapted from Last (2019, p. 9).

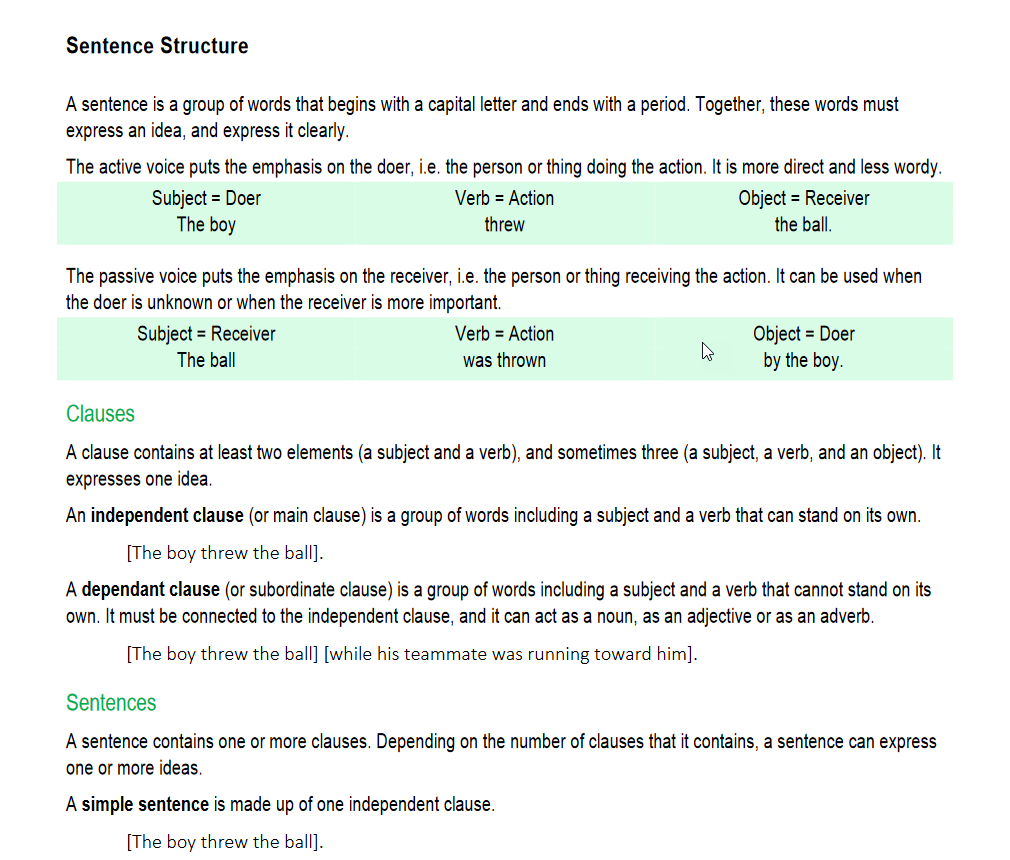

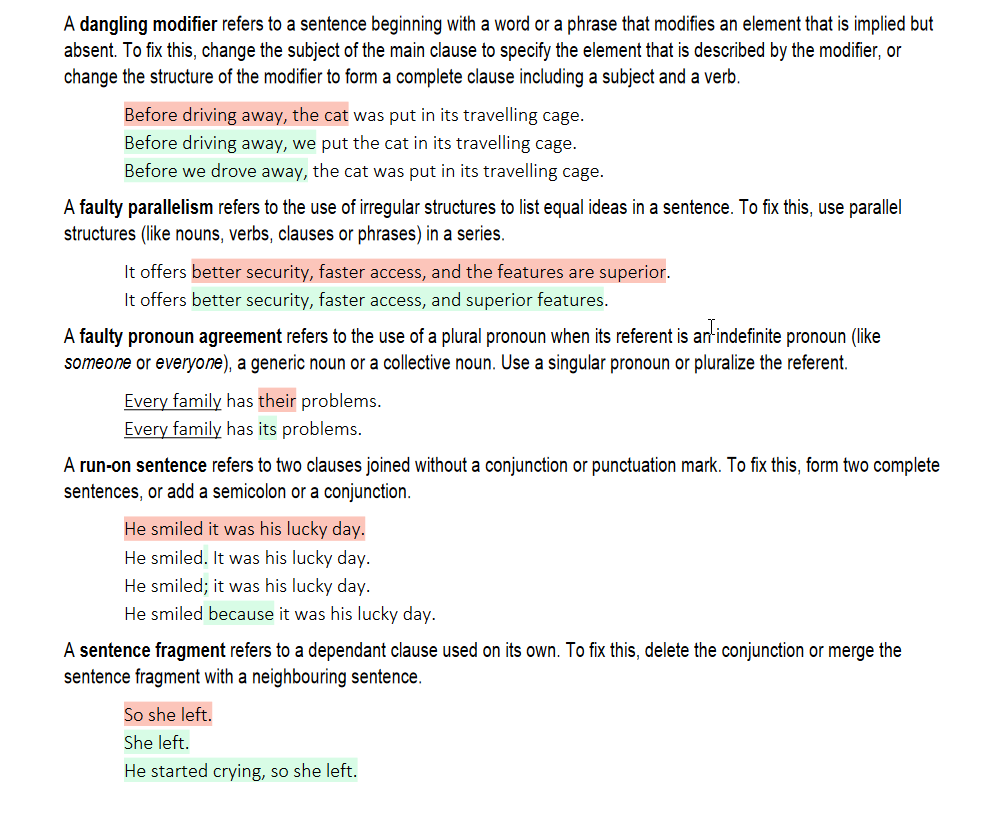

Remember to edit, revise, and proofread your message before sending it to your instructor. The following multipage handout, from the Academic Writing Help Centre, Student Academic Success Service, University of Ottawa (2016), may be helpful in this regard.

Sentence Structure

https://sass.uottawa.ca/sites/sass.uottawa.ca/files/awhc-sentence-structure.pdf

References

Academic Writing Help Centre, Student Academic Success Service, University of Ottawa. (2016). Sentence structure. License: CC-BY 4.o. https://sass.uottawa.ca/sites/sass.uottawa.ca/files/awhc-sentence-structure.pdf

Last, Suzan (2019). Technical writing essentials: introduction to professional communication in the technical fields. License: CC-BY-SA-3.0. Retrieved from https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Letessier, T.B., Mouillot, D., Bouchet, P.J., Vigliola, L., Fernandes, M.C., Thompson, C., Boussarie, G., Turner, J., Juhel, J.B., Maire, E., Caley, M.J., Koldewey, H.J., Friedlander, A., Sala, E., & Meeuwig, J.J. (2019). Remote reefs and seamounts are the last refuges for marine predators across the Indo-Pacific. PLoS Biology, 17(8), e3000366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000366

Lexico. (2020). Integrity. In Lexico. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/integrity

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2018). Threats to coral reefs: Overfishing [Infographic]. https://www.noaa.gov/multimedia/infographic/infographic-how-does-overfishing-threaten-coral-reefs

Northwest Vista College Library. (n.d.). Creative Commons matching game. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://nvcguides.libguides.com/ccmatchinggame

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Comparative essays. License: CC-BY-SA 4.0. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/comparative_essays.pdf