Maintaining a Productive Writing Schedule

Dawn Atkinson

Introducing the Chapter

This chapter aims to help you think carefully about procrastination and recognize what it means to maintain a productive writing schedule by considering how professional writers—“writers who exhibit recognized skill in [an area] coupled with an ability to earn part of all of their living by deploying that skill” (Atkinson, 2020, p. 481)—sustain momentum in their work. In addition, it discusses ideas for overcoming writing anxiety that you might apply to your own writing processes to improve satisfaction with your academic efforts.

Exploring Procrastination

Writing can be challenging, particularly when procrastination affects a writer’s potential to proceed with a project in a productive way. Procrastinating means avoiding work on something that needs to be done. Although some writers may think about their writing projects and how to tackle them during the delays, procrastination for others can lead to rushed work with little time left for polishing before deadlines. In these instances, procrastination can contribute to substandard writing.

Complete the following personal inventory, which is adapted from Nissila (2016, pp. 38-41), to explore reasons for procrastination in college.

-

- I am lazy when it comes to getting my academic work done.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I am disorganized when trying to complete my academic work.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I have difficulty saying no to others, which puts me behind in my academic work.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I feel that I will succumb to procrastination no matter what.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I don’t think I have the organizational abilities to stop procrastinating.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I put off writing papers until the night before they are due.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I work best under pressure, so I think that procrastination is really good for me.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- When what I have to study or accomplish is just not that important to me, I find it tempting to procrastinate.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I have a hard time convincing myself to maintain a positive attitude about avoiding procrastination.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I think I have more time to finish things than I usually do.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- Some instructors assign too much homework and don’t seem to understand that I have a life outside of school. I believe it’s their fault that I have to procrastinate.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- Spending time with my friends gets in the way of doing homework.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I can’t seem to stay away from social media.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I get wrapped up in family matters and lose track of study time.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- ________________________________________________________________________ also causes me to procrastinate.

- Most of the time

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

Taking into account your personal inventory responses, select your top five reasons for procrastinating and write them in the table below.

Reason What I Can Do 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Now read a handout entitled “Procrastination” (The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2019), which can be found at https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/procrastination/. While reading, complete the table by listing ways to counter your reasons for procrastinating.

Which ideas do you plan to try? What challenges do you foresee in using these ideas? How will you meet the challenges?

Focusing on How Professional Writers Maintain Productive Writing Schedules

Professional writers work in a variety of different roles. Some earn the majority of their livings from writing novels, textbooks, and news articles, for example, while others do a great deal of writing in the workplace when preparing instructions, proposals, letters, memos, presentations, reports, emails, and journal articles.

Given the centrality of writing to the above-mentioned groups’ livelihoods, they oftentimes develop self-regulation tactics to remain maximally productive during writing projects. To expound on this point, Kellogg (2008, pp. 12, 13) reported that interruptions during writing periods slow writing progression, leaving an author unable to focus intently on the processes necessary for composing effective sentences and paragraphs: planning what to say, committing thought to written form, and reviewing text already produced. We can infer from this finding that prolific authors minimize distractions to devote their full attention to writing tasks. Kellogg also found that prolific authors tend to develop, craft, and refine text over multiple sessions rather than trying to pen optimal pieces of work during one-off extended binges. He contended that the latter approach can result in anxiety, frustration, and fatigue (p. 18), undesirable outcomes for individuals whose successful job performance relies on their consistent capacity to deliver quality written text. As in cases of procrastination, binge writing can also lead to sub-standard work when an author has little time left to edit and revise before a deadline. Babin et al. (2017, p. 140) added that professional writers make writing a habit, a customary action in other words, rather than waiting for ephemeral moments of inspiration to inject momentum into their projects.

In research that focused on how two highly skilled writers composed different types of textbooks for English language teaching, Atkinson (2020) found that the authors used certain tactics to maintain productive writing schedules. One of the authors, for instance, intentionally wrote textbook content in the mornings because she felt most productive then (p. 497). She also composed textbook content for limited amounts of time each day to counter the negative effects of binge writing and writer’s block (p. 497), defined as the inability to produce written text (Babin et al., 2017, p. 141). Both participants in the Atkinson (2020) study also purposefully used the writing process of incubating to maintain productivity and develop quality textbook content. Incubating refers to taking time away from writing with the aim of unconsciously solving a problem related to the writing project at hand (p. 490). This approach differs from procrastinating since incubating is deployed to solve problems rather than to delay work. The textbook authors both engaged in physical activity while incubating to encourage problem solving: one author rode his bike and played drums (p. 491), while the other went for walks (p. 496). The former also experienced the positive effects of incubating even when taking short drink breaks during writing episodes (p. 491). The research found that incubating enabled the writers to tackle problems unconsciously outside of composing sessions rather than during them when their mental resources were occupied with creating original textbook content (p. 496).

Taken together, the literature discussed here outlines practical self-management strategies that professional writers use to maintain productivity. What are your thoughts about these strategies? Can you envision them working for you? Why or why not?

Overcoming Writing Anxiety

- I am lazy when it comes to getting my academic work done.

- To maintain a productive writing schedule, a writer must find ways to address anxiety about writing projects so that worry and fear do not evolve into the paralysis that characterizes writer’s block. The previous section in this chapter mentioned tactics that professional writers use to manage the challenges associated with writing. The current section and the chapter conclusion, which are adapted from Babin et al. (2017, pp. 140-146), elaborate on what writing anxiety is and means for countering it.What is Writing Anxiety and How Do You Know if You Have It?Do you worry excessively about writing assignments? Do they make you feel uneasy or agitated? Do you have negative feelings about certain types of writing? If you answered yes to any of these questions, you might suffer from writing anxiety. Writing anxiety simply means that a writer experiences negative feelings about a given writing task. The last of the questions above points out something important about this condition that has been afflicting writers everywhere for centuries: writing anxiety is often more about the audience and/or purpose for a given writing task than it is about the mere act of writing itself.Let us consider the situational nature of writing anxiety for a moment. Say you just bought a new pair of headphones. You brought them home, removed all the packaging, plugged them in, and they are amazing. So you decide to visit the company website, and you write a stellar review of the product that includes descriptive details about its comfortable fit, excellent sound quality, ability to cancel outside noise, and reasonable price.

The next day in biology class your instructor covers the topic of biomes, and you learn about animal habitats and biodiversity and the interrelation and interdependence of species within biomes. You find it fascinating and cannot wait to learn more. But then something terrible happens. Your instructor assigns a research paper on the subject. As your instructor begins to describe the length and other specifications for the paper, complete with formatting guidelines, citation requirements, and a reference list, your palms start to sweat, your stomach feels uneasy, and you begin to have trouble focusing on anything else your instructor has to say. You are experiencing writing anxiety.

Writing anxiety is the condition of feeling uneasy about writing. But your condition is not about the act of writing. Just yesterday you wrote a great review for those new headphones. So why do you suddenly feel paralyzed by the thought of writing the biology research paper? Let us consider some possible causes.

- What Causes Writing Anxiety, and How Can It Be Thwarted?The causes of writing anxiety are many. Here are just a few.

- Inexperience with the type of writing task

- Previous negative experiences with writing (e.g., someone, maybe a teacher, said negative things about your writing)

- Negative feelings about writing (e.g., “I’m not a good writer”; “I hate writing”)

- Immediate deadline

- Distant deadline

- Lack of interest in the topic

- Personal problems or life events

Level of experience may explain why you felt comfortable writing the headphone review while you break out in a sweat at the thought of the biology paper. If you have never written anything similar to a particular assignment, maybe you feel unsure about whether you can meet the assignment requirements or the teacher’s expectations. Or maybe the last time you turned in a writing assignment, you received negative feedback or an unsatisfactory grade. Maybe you procrastinated most of the semester, and now the paper is due next week and you feel overwhelmed. Or maybe it is the second week of the semester and the finals week deadline seems so far away that you are not motivated to write.

Knowing the cause of your writing anxiety can help you move beyond it and start writing, even if you cannot completely eliminate your apprehension. If the topic does not interest you or if you are having problems at home, those probably are not issues that will just disappear, but if you try some of the following strategies, you may find that you can at least move forward with even the most anxiety-inducing writing assignments.

Just Start Writing

Half the battle with writing is just getting started. Try some of the following brainstorming strategies to help jumpstart this task.

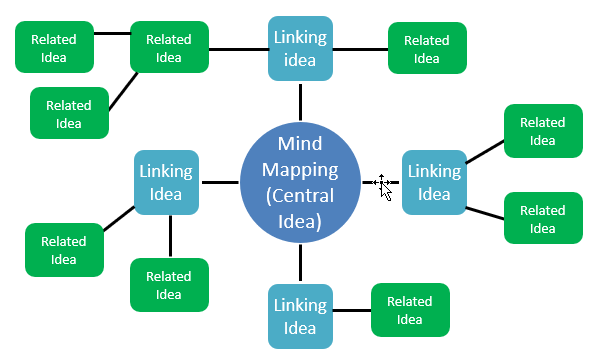

Mind mapping is a way to brainstorm by drawing connections between ideas. This technique is also referred to as clustering, tree diagramming, and spider diagramming. Create a mind map by following these steps.

- Write the central idea you wish to focus in the center of a page or screen.

- Circle the central idea.

- Think of ideas that link to the central idea; write these around the central idea, and draw connecting lines from the central idea to the linking ideas.

- Think of ideas that relate to the linking ideas and ultimately back to the central idea; write them around the linking ideas, and connect them to the linking ideas with lines.

Here is an example of a mind map.

Notice that you can use color and type size to create organization and emphasis.

Listing involves making a list of ideas. You might decide to note down ideas related to your topic in a free-form manner. When using this approach, write down whatever you can think of that is relevant to the topic; you can always eliminate unnecessary material later. Your second option is to split your list into two columns: (1) what you know and (2) what you do not know but need to find out through research.

Outlining organizes ideas about a topic using a grouping or visual cuing system. A formal outline uses a numbering and indentation scheme to help organize ideas. Generally, you begin with your main point, then you list subtopics that pertain to or support the main point, and lastly you flesh out details underneath each subtopic. Each subtopic is lettered or numbered and has the same level of indentation. Details under each subtopic are given a different style of number or letter and are indented further to the right. The expectation is that each subtopic will merit at least two details. Here is an example of a formal outline.

- Major Idea

- Supporting Idea

- Detail

ii. Detail - Supporting Idea

- Detail

ii. Detail

iii. Detail

Freewriting is a means of generating text by writing anything that comes to mind about a topic. To get your mind working, you might start with the prompt “What do I already know about this topic?” If you started with a list or an outline, you can also freewrite about each item. The following tips apply to freewriting.

- Write as much as you can, as quickly as you can.

- Do not edit or cross anything out. (Note: if you feel you must edit as you go, just write the correction and keep moving along. The aim is to record ideas on the page rather than search for the perfect word.)

- Keep writing or typing the whole time.

- Feel free to follow a tangent—you do not need to stay on topic or write in any order.

- Write a repeating phrase if you get stuck (e.g., “I don’t know what to write”) until your brain gets tired and you think of how to proceed.

Looping builds on freewriting by exploring many related ideas about a topic, sometimes in depth. Here are instructions for looping.

- Set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes.

- Freewrite until the timer sounds.

- Read what you have written.

- Circle or underline any text that needs to be fleshed out or that introduces new ideas.

- Select one of the circled or underlined segments for your next loop.

- Freewrite again for the same amount of time, using the idea you selected from the first freewrite.

- Repeat until you feel you have covered the topic or are out of time.

Asking questions stimulates ideas for a paper’s content by using probing queries, such as those listed below.

- Problem/Solution: What is the problem your writing is trying to solve? Who or what is part of the problem? What solutions can you think of? How could each solution be accomplished?

- Cause/Effect: What is the reason behind your topic? Why is it an issue? Conversely, what is the effect of your topic? Who will be affected by it?

- The five Ws plus so what:

- Who: Who is involved? Who is affected?

- What: What is happening? What will happen? What should happen?

- Where: Where is it happening?

- When: When is it happening?

- Why/How: Why is this happening? How is it happening?

- So What: Why is the topic important? Why should readers care about it?

When beginning work on a paper, sometimes the biggest roadblock is thinking that the writing needs to be grammatically pristine and optimally organized right from the start. The strategies outlined in this section provide an alternative: they offer opportunities to express your raw ideas so that you can find ones to pursue further and save polishing until later.

Create Smaller Tasks and Short-Term Goals

One of the biggest barriers to writing can be that the task just seems too large, and perhaps the due date is weeks away. Each of these conditions can contribute to feelings of being overwhelmed or to the tendency to procrastinate. But the remedies are simple and will help you persist and work toward your deadline and a finished product: (1) divide large writing tasks into smaller, more manageable tasks, and (2) set intermediate deadlines.

Imagine you have a term paper that is assigned during week one of a 15-week term, and it is due during finals week. Make a list of all the tasks you can think of that need to be completed, from beginning to end, to accomplish the assignment requirements. List the tasks, and assign yourself due dates for each of them. Consider creating a detailed task breakdown like the one in Table 1, which includes a column for notes specific to the assignment.

Task Complete By Notes Brainstorm topics and select one to focus on Week 2: Wednesday Conduct initial research to learn about the topic, and develop a list of search terms for more in-depth research Week 3: Friday Ask the instructor to look over my search terms Search library holdings and databases using search terms Week 4: Friday Ask a librarian for help with using databases Read sources and take notes Week 6: Friday Consult the notetaking examples in my textbook Create an outline, and begin writing the paper Week 7: Monday Try freewriting to generate ideas for the outline Complete a draft of the paper Week 8: Thursday Ask a classmate to read the draft and provide feedback Week 8: Friday Arrange this with a classmate the week before Revise the paper based on feedback Week 9: Thursday Meet with the instructor to ask questions about the draft Week 10: Friday Make a list of questions before the meeting Do additional research if necessary Week 11: Monday Revise the draft paper Week 12: Wednesday Meet with a writing center tutor to go over the draft, and edit and revise it Week 13: Friday Contact the writing center the week before to arrange an appointment Make sure the formatting, citations, and references are correct Week 14: Wednesday Proofread the paper and make final revisions Week 14: Friday Submit the paper Week 15: Monday Table 1. A detailed schedule for completing a semester-long writing project

Creating and following a schedule, such as that outlined in Table 1, will help you divide a writing project into manageable tasks that can be completed in a timely way without becoming overwhelming.

Collaborate

Get support from a friend, family member, or classmate, and talk to a tutor in your college writing center about your ideas or organizational plan for your paper. Sometimes talking about your ideas is the best way to develop and expand them. Remember to take note on your conversation to avoid forgetting a useful idea. Classmates are also a great resource because they are studying the same subject as you, and they are working on the same assignments. Talk to them often, and form study groups. Ask them to look at your writing and give you feedback. In addition, set study group goals, and hold one another accountable for meeting deadlines.

Embrace Reality

Focus on the reality of your assignment.

- Focus on what you do best rather than worry about your perceived weaknesses.

- Acknowledge that writing can be difficult and that writing skills can be improved with effort and time.

- Recognize what might be new or unfamiliar about the type of writing that you are doing.

- Understand that confusion and frustration is a natural part of experiencing new things.

- Remember that you are a student and are supposed to be experiencing things that are unfamiliar (e.g., new genres, new formatting conventions, new citation and referencing styles, new audiences, new subject matter, and new approaches).

Seek Out Experienced Writers

If you can, find more experienced writers and ask them questions. Sometimes, this might be a friend or family member who has already taken college courses. Maybe it is a fellow student who has already taken the class you are in now. Also, the tutors in your college writing center can be a big help at any stage in the writing process. And do not forget to ask your instructor for suggestions or assistance.

Another way to learn from the experience of others is to look at examples of the types of writing you are doing. How is the piece organized? Does it use source material? What sort of tone does it use? If you do not know where to find examples, ask your instructor for help.

Consider Environmental Factors

Realize that some aspects of writing are not about the inner workings of your mind as a writer. Some factors that affect writing productivity are external. For example, multitasking, or switching between tasks, oftentimes lengthens the time required to finish tasks versus completing them one by one. So put away your phone and switch off other distractions like social media and the television. Find a quiet place to work where you will not be disturbed. And make sure you have everything you need as you get started: pens, pencils, sticky notes, highlighters, notebooks, textbooks, a computer, snacks, drinks, and whatever else you need to be productive and feel comfortable. Allot a set period of time to each task, and attend to each one separately.

Drawing the Chapter to an End

Hopefully the information and tips presented in this chapter will help you to make productive use of your time, to get started writing, and to sustain momentum. Try the various strategies outlined here, and if something does not work well, move on and try something else. Select the strategies that work best, and modify them to suit your needs.

Activity A: Considering Writing Obstacles and How to Overcome Them

This in-class activity, which is adapted from Babin et al. (2017, p. 146), asks you to spend three minutes listing instances when writing was difficult for you. Your list does not need to focus exclusively on times when you were writing for classes, although you should consider those occasions. Also consider other writing situations, such as scholarship or job applications, thank-you letters, or emails to coworkers or school officials. Afterwards, pick out one of the instances on your list and spend several more minutes considering what barriers or obstacles made it hard to write in that situation. Was it

- Inexperience with the type of writing?

- A previous negative experience with writing?

- An immediate deadline?

- A distant deadline?

- A lack of interest in the topic?

- Personal problems or challenges?

- Something else?

Discuss your list of writing obstacles with classmates in a small group. Then, as a group, try to identify some strategies or good writing practices discussed in this chapter that might have helped you overcome those obstacles. If class time allows for it, your group might share its ideas with the class.

Activity B: Constructing and Integrating In-Text Citations

To help build your confidence as a writer, this activity asks you to decide which of the items presented include acceptable APA in-text citations and integrate them correctly. Mark each box with a P for acceptable or an X for unacceptable, paying particular attention to punctuation when making your decisions. Consult the in-text citation information in the “Reporting Research Outcomes” chapter of this textbook for help when completing this activity, and be prepared to discuss your responses and rationales for them in class.

Items √ X 1 “In our increasingly technological and internationalized workplaces, communications skills are among the most sought-after competencies employers require of job candidates” (Last, 2019). 2 “In our increasingly technological and internationalized workplaces, communications skills are among the most sought-after competencies employers require of job candidates” (Last, 2019, p. 1). 3 “In our increasingly technological and internationalized workplaces, communications skills are among the most sought-after competencies employers require of job candidates (Last, 2019, p. 1).” 4 According to textbook writer Last, “Every job posting you see will almost certainly ask for candidates with excellent communications skills and the ability to work effectively in teams” (Last, 2019, p. 1). 5 According to textbook writer Last, “Every job posting you see will almost certainly ask for candidates with excellent communications skills and the ability to work effectively in teams” (2019, p. 1). 6 According to textbook writer Last (2019), “Every job posting you see will almost certainly ask for candidates with excellent communications skills and the ability to work effectively in teams” (p. 1). 7 According to textbook writer Suzan Last (2019), “Every job posting you see will almost certainly ask for candidates with excellent communications skills and the ability to work effectively in teams” (p. 1). 8 “The ability to communicate clearly and effectively in written, verbal, and interpersonal contexts is vital for success and advancement in the workplace.” (Last, 2019, p. 1). 9 “The ability to communicate clearly and effectively in written, verbal, and interpersonal contexts is vital for success and advancement in the workplace.” (Last, 2019, p. 1) 10 “The ability to communicate clearly and effectively in written, verbal, and interpersonal contexts is vital for success and advancement in the workplace” (Last, 2019, p 1). Homework: Interviewing an Experienced Writer about Writing Processes

Identify a more experienced writer than yourself, such as a friend, family member, professor, adviser, writing tutor, career center director, work supervisor, work colleague, or someone who is employed in a career you are interested in. Interview that person about his or her writing processes, or ways of getting writing done. Afterwards, address the items listed below in a memo, and remember to cite and reference any outside sources of information that you use.

- Summarize the results of the interview by focusing only on main themes—do not give a play-by-play of who said what and in what order and who responded.

- Discuss how the interviewee’s responses compare with your own writing processes.

- Identify any writing processes your interviewee uses that you want to try, and explain why. Alternatively, identify any writing processes your interviewee uses that you want to avoid, and explain why.

Consult the “Interviewing for Information” chapter of this textbook for help with preparing for and carrying out your interview and the “Writing Print Correspondence” chapter for guidance when writing and formatting your memo.

Remember to edit, revise, and proofread your memo before submitting it. The following handouts, “Temporal, Spatial & Directional Prepositions” (McNamee, 2019) and “Capitalization” (LaRoche, n.d.), may help in this regard.

- Capitalization

References

-

Atkinson, D. (2020). Engaging in textbook writing as deliberate practice: How two expert ELT textbook writers use metacognitive strategies while working to sustain periods of deliberate practice. Journal of Writing Research, 11(3), 477-504. doi:10.17239/jowr-2020.11.03.03

Babin, M., Burnell, C., Pesznecker, S., Rosevear, N., & Wood, J. (2017). The word on college reading and writing. Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC-BY-SA. Retrieved from https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/

Kellogg, R.T. (2018). Professional writing expertise. In K.A. Ericsson, R.R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, & A.M. Williams (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (2nd ed., pp. 413-430). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480748

LaRoche, A. (n.d.). Capitalization. Yuba College Writing & Language Development Center. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://yc.yccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CapitalizationAccessibleMarch2019.pdf

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials: Introduction to professional communications in the technical fields. University of Victoria. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

McNamee, K. (2019). Temporal, spatial & directional prepositions. Colorado School of Mines Writing Center. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://www.mines.edu/otcc/wp-content/uploads/sites/303/2019/12/otccprepositionslesson.pdf

Nissila, P. (2016). How to learn like a pro! Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/collegereading/

The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (2019). Procrastination. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/procrastination/