Reflecting on Performance

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

The current chapter emphasizes the value of reflecting on performance and provides guidance for writing assignments that center on this activity. Reflecting on performance means to carefully consider how you undertook something, the results of your efforts, and how you can apply the knowledge moving forward.

Chapter Introduction

As an introduction to the importance of reflecting on performance, read an article entitled “Reflecting on Work Improves Job Performance” (Nobel, 2014), which can be found at https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/reflecting-on-work-improves-job-performance. Afterwards, work with a small team to complete the following tasks based on your understanding of the reading.

- Identify the main point of the article.

- Identify the evidence used to support the main point.

- Discuss whether you agree with the main point, and supply explanations for your answers.

- Discuss how the article applies to a student’s academic work in college.

- Present your group’s findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Self-Regulated Learners Reflect on Performance

When people reflect on performance, they focus on things they have done previously—by taking a close, honest look at personal beliefs, actions, and expectations—with the aim of improving future endeavors. To better understand how reflecting on performance might be applied in an academic setting, read the following case study and the information that accompanies it, which are adapted from the Supporting and Advancing Geoscience Education at Two-Year Colleges project (SAGE 2YC, 2017).

Case Study: Tina’s Understanding of Her Efforts in College

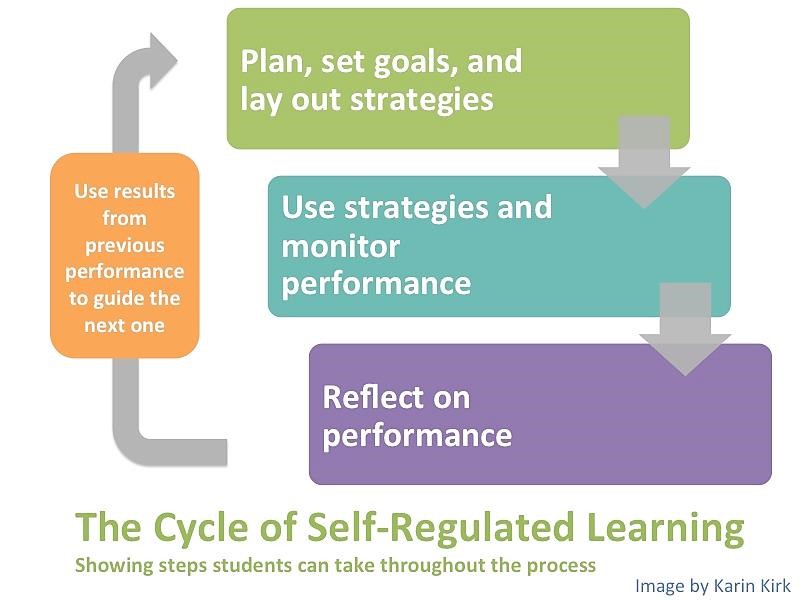

Although Tina feels discouraged, by redirecting her time and energy to more effective ways of tackling assignments, she can likely bring about a more rewarding academic experience, which, in turn, can boost her motivation and feelings of self-efficacy (her belief in her capacity to achieve goals). This statement is likewise true for all students. Key to making progress is learning how to reflect on one’s own processes, a step that is integral to the cycle of self-regulated learning illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Phases of the self-regulated learning cycle (Kirk, 2017)

In the cyclical process of self-regulated learning, a student plans for a task, monitors his or her performance, and then reflects on the outcome. The cycle then repeats as the student uses the reflection to adjust and prepare for the next task. We will now take a closer look at how to implement steps in the cycle.

Phase 1: Plan, Set Goals, and Lay Out Strategies

Before you begin working on a task for a class, establish a plan for completing it so that you can be efficient with your time and effort. The following prompts can help you develop a plan.

- Analyze the learning task. Is it a task you have done before, or is it something new? Does it build on a homework or in-class activity you completed in the past? How much time will it take? How much focus will you need?

- Set goals. How will you structure the task? What are the intermediate checkpoints and sub-goals? For example, can you complete an outline with two weeks to go and then a rough draft one week prior to the due date? That plan would likely allow you time to seek out extra help as needed.

- Plan strategies. Will you need resources from the library, and how can you go about finding them? Will you need to book appointments with a writing tutor and your instructor? Given your needs, when should you get started on the task?

- Set expectations for the outcome. Given how much time you have available, your strengths and weaknesses, and your current standing in the course, what type of outcome would you like?

- Work out how to proceed if obstacles arise. For example, if you do not understand some of the assignment directions, plan to ask the instructor for clarification during office hours.

Phase 2: Use Strategies and Monitor Performance

In this phase, proceed with your plan. Because you have already created the plan, you can now focus exclusively on carrying it out. Here are some key points to consider as you work through this phase.

- Think carefully about the actions you take and their effectiveness. For example, you might think, when I studied in a quiet location in the library, I completed the reading more quickly than when I read at home. Record the observations in a notebook for future reference. Some instructors require students to write reflective assignments, and your record of observations may be useful for that type of assignment.

- Monitor progress on your goals and sub-goals.

Phase 3: Reflect on Performance

Reflect on the outcome of your efforts: in other words, think about how you did on a particular assignment, why you earned the score you did, and how you can use the knowledge to improve future outcomes. Take into account the following points while reflecting.

- Compare your performance to your main and sub-goals rather than comparing it to other students’ performance. Reflection requires looking inward for answers rather than looking at how others did or placing blame on other students or the instructor.

- Consider the effectiveness of your plan. Did it produce the outcomes you aimed for? If not, what changes will you make to a plan for a future assignment? How did your timeline for achieving sub-goals work out? What changes would you make to a similar timeline in future?

- Consider the effectiveness of the individual strategies you outlined as part of your plan. Did you implement the strategies? Did you select appropriate strategies? If not, what other strategies can you try next time?

- Use your thoughts about your performance to plan for a future task. How will you adapt your approaches to planning, using strategies, managing time, and monitoring your performance?

Again, the phases outlined here are cyclical, meaning that they should continue during a semester and throughout your academic career as you refine your approaches to assignments.

To draw this section to a close, writing is a skill, and skills can be developed with work. For the work to be maximally productive, a writer needs to consider the tactics he or she uses when preparing assignments and how those tactics might be modified when preparing future assignments to produce different results. In other words, the writer needs to reflect on performance.

Guidance for Writing an Assignment that Asks for a Reflection on Performance

If your instructor assigns a paper that requires a reflection on performance, you may be asked to do the following:

- Discuss what you did and why.

- Reveal the results of your actions.

- Identify what you learned as a result of the experience.

- Articulate how you will apply what you learned to future experiences.

Notice that the list is numbered, which indicates that the steps proceed in a sequential order. In other words, to establish context for the reader’s benefit, you must first discuss what you did before writing about how you will apply the knowledge gained through the experience to future endeavors.

Although the list above provides a skeleton outline for writing a reflection on performance, you may also use pre-writing strategies to build momentum for your paper, to assemble connections between your thoughts and what the assignment asks you to do. To begin compiling thoughts about the assignment, read through your notes about the actions you took and the effectiveness of the results (see “Phase 2: Use Strategies and Monitor Performance”). Afterwards, try a free-writing activity to see what further ideas come to mind about the assignment. The following directions for free-writing are adapted from Wilfrid Laurier University (n.d., “Free-Writing Activity”).

- Set a timer for three minutes.

- Write freely and honestly about your experience until the timer buzzes.

- Review what you have written.

- Underline keywords or ideas that might require further exploration or thinking.

- Set the timer for another three minutes.

- Write freely and honestly about the keywords or ideas that you underlined until the timer buzzes.

- Review what you have written.

- Think about how you might use the free-writing notes to reflect on performance in your assignment.

- Disregard extraneous or off-topic information from your free-write when producing your draft.

Once you have compiled some initial ideas for the assignment through free-writing, you may also decide to create an outline to formalize plans for your paper. Use the first set of numbered steps in this section as a starting point for an outline.

Guidance for Writing a Reflective Portfolio Letter

Some university writing instructors use portfolios, collections of coursework, to gauge students’ academic performance over the course of a semester, and a reflective cover letter typically accompanies this type of assignment. A reflective cover letter introduces the portfolio’s contents and discusses whether and how the pieces evidence meeting course requirements, or demonstrate progress toward long-term goals, or both. The letter is an argumentative text, meaning that it must clearly tie evidence and reasons to statements about progress in order to persuade the instructor or other readers of the validity of claims. To create these necessary links in the letter, think carefully about which pieces of evidence align best with course requirements, and reflect on how the class helped you to develop requisite skills. As with any piece of correspondence, a portfolio cover letter should maintain a respectful tone towards readers and follow established design, organization, and source attribution conventions. Remember too that the cover letter is an artifact used to evaluate course performance, so it should also follow standard spelling, grammar, capitalization, and punctuation conventions for maximum readability.

Use an introduction, body, and conclusion format when writing a portfolio cover letter. The following list, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020, para. 5), provides further guidance about how to structure this type of letter.

- In the introduction, provide readers with a little background about yourself as a writer. Where were you starting from as a writer when you began the course? Describe your past experience as a writer without going into extensive detail.

- At or near the end of the introduction, provide a thesis statement that makes a clear assertion about your growth as a writer and what readers can expect to see in the portfolio.

- In the body paragraphs, discuss each piece of the portfolio. Give specific examples of your work, your revision, and what you learned. Make sure to address the outcomes or goals of the course. How does your work reflect meeting these outcomes? You may need several paragraphs or pages to make your case, so be sure to review length specifications for the assignment.

- In the conclusion, explore your continued challenges as a writer: acknowledge where you want to go, but remind readers that you have grown and made improvements thanks to your work in the course. Rather than focusing on new information, the conclusion should follow on from points discussed in the body of the letter.

This structure will help create a portfolio letter that is appropriately reflective and logically developed.

Activity A: Work with a Sample Portfolio Cover Letter

Read the sample portfolio cover letter that follows, which is adapted from MacMillan (2015, as cited in Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020, “Sample Portfolio Letter”). Afterwards, identify its components using the numbered list of items presented directly above this activity. Write the components in the margin.

May 9, 2020

Dear Portfolio Committee:

My name is Sally Student, and I am pursuing a nursing degree to become an RN and dedicate my life to helping others. When I entered Writing Foundations class in January, I had little knowledge about core writing skills and argumentation. My high school did not have English classes that focused on writing; instead, we read short stories and completed grammar worksheets. I’ve always liked to write reflections and creative pieces for personal enjoyment, but more formal, purposeful types of writing intimidated me. Although week one of Writing Foundations was overwhelming, as I was unfamiliar with basic terminology to do with writing, I am proud to have persevered, developing confidence all the while. Furthermore, in the process, I gained beneficial knowledge that I can take with me into other classes and my career. Specifically, I learned to perform solid academic research to support my ideas, learned to combine my thoughts with the works and opinions of others, received further education on developing a better writing process, and learned to tailor my writing for different readers. I also learned to use many elements fundamental to strong writing, such as thesis statements, paraphrases, and summaries. In short, the things I learned in Writing Foundations class have helped me to develop into a stronger, more flexible writer.

This portfolio contains three papers and accompanying draft materials to exemplify the skills I have learned in Writing Foundations. The first paper is a persuasive argument on language discrimination. The class used assigned articles for the paper, and from those sources we took a position on whether language discrimination occurs and, if it does, what the effects might be on persons who experience the discrimination. The second paper was a researched argument essay for which we had to pick a topic and perform scholarly research on our own. I chose to research the psychological effects of child beauty pageants on the young participants and argued that these competitions negatively impact self-esteem and may place children at risk of exploitation. The third paper was an in-depth analysis of an article on the new iPad. The professor assigned the article, and students were to examine its argumentative components in order to evaluate its effectiveness.

Upon completion of Writing Foundations, students are supposed to understand how to perform and document scholarly research. This means that we should know how to locate academic articles using reliable resources. Furthermore, it means that we leave the course knowing how to smoothly incorporate the articles we find into an argument and to cite them correctly. Paper two most clearly demonstrates my work in this area. During the process of writing this essay, I learned to use Academic Search Premier and other library databases to locate peer-reviewed, academic materials on the exploitation of children through child beauty pageants. After finding numerous articles, I read and annotated the key information before creating a written map linking the various articles together. I then used my findings to develop a thesis and support for my argument. My thesis ended up being, “Beauty pageants are not a healthy activity for children because they force young girls to act like adults, exhibit age-inappropriate sexuality, and have negative body image and mental health problems later in their lives” (Student, 2020, p. 2). To support this position, I used articles from the scholarly publications PLoS ONE, Eating Disorders, and Science. Throughout the essay, I paraphrased or summarized from these sources as needed and documented the texts with APA in-text citations and accompanying reference list entries. Knowing how to perform proper academic research has made my writing stronger by giving me the fundamental tools I need to locate sources that are more reliable than the average internet article.

Another goal of Writing Foundations was to teach us to combine our thoughts and opinions with the ideas, viewpoints, and works of others. Doing so requires interpreting another person’s argument and either using it to support our ideas or disputing it based on its weaknesses. My work on all three of the previously mentioned papers met this goal. For each of the assignments, we were required to read the works of others and interpret them in order to form an original argument. Importantly, I learned that incorporating viewpoints different from my own in a paper can actually help strengthen my argument since it shows that I have done a thorough job of research and can discuss more than one side of an issue. In the essay on beauty pageants, for instance, I included arguments from beauty pageant proponents, explaining that many supporters see the events as springboards to lucrative careers in the modelling and entertainment industries (Student, 2020, p. 4). After exploring this alternative position, I asked my readers if these perceived benefits outweigh the serious risks I mentioned earlier in the paper. The alternative viewpoint and the information I used to refute it are the voices of other people combined with my own take on the situation. The whole experience has strengthened my writing ability by teaching me to look for the strengths and weaknesses in an argument and use them to express what I think.

Writing Foundations was also designed to give students more practice with engaging in the writing process, or the steps taken to produce a strong piece of written work. These steps, which occur in repeated sequences, can include researching, notetaking, prewriting, drafting, peer reviewing, editing, reflecting, and revising. I used these steps when preparing all three of my assignments. I began by analyzing the written works of others and writing notes on them and then used those notes to form an argument and a thesis. The next step was a prewriting assignment followed by a first draft. After the first draft was complete, I participated in peer review sessions and consultations with my professor. After some personal reflection, I reworked my draft according to the suggestions and my new ideas. Then, I repeated the review and drafting steps until I developed the final product. The writing process helps me produce stronger work because it requires me to constantly re-evaluate what I am doing. The steps offer multiple opportunities to correct mistakes and clean up assignments. If I tried to turn in my first draft as a final draft, I would lose out on those opportunities to rethink my work. The writing process is something I thoroughly enjoy about writing, and I’ve come to realize that the only way to learn it is to experience it.

A fourth goal of Writing Foundations was to help us understand how to adjust our texts for different readers. To assist with this goal, the professor specified audiences for each of the assignments. While our first and third papers were intended for academic readers, the researched argument essay was written with an audience specific to our topic in mind. For my essay on beauty pageants, I targeted parents, as I felt they should be aware of some of the important issues surrounding these events, and I learned how to make content and style decisions based on my audience. When writing the essay, I wanted to find credible source material that would be convincing to parents. Having a thorough research process helped me with this effort, but I did have to make some strategic decisions about what to include and omit when writing the assignment to meet readers’ needs. Adjusting content and style for an audience is a skill that I will take with me and use in my other courses and future career.

As this letter explains, Writing Foundations taught me to perform solid research with reliable sources, blend my voice with the voice of others by analyzing their work, utilize the steps in the writing process to produce strong texts, and understand how audience considerations can help me become a more effective—and flexible—writer. I am now able to state my perspective more clearly and convincingly than I could to do at the beginning of this course. While I still have much learn about writing and the situational flexibility it requires, I feel I have made considerable strides in Writing Foundations. In future writing courses, I look forward to learning about discipline-specific styles of writing and developing longer, more complex arguments using the skills I’ve learned. Upon viewing the samples in my portfolio, I hope you will agree that I am ready to proceed to another writing course to further my writing development.

Sincerely,

Sally Student

Having read and identified the components of this portfolio cover letter, now identify what makes it effective. Be specific in your response so you can discuss your ideas in class.

Now identify areas for improvement in the letter. Again, be specific in your response so you can discuss your ideas in class.

By analyzing and evaluating the sample, you may better understand how to compose a portfolio cover letter for a course.

Activity B: Work with Your Writing Assignment Feedback

Reflect on your performance in this writing course by revisiting your assignment feedback to identify positive aspects of your documents and areas for improvement, particularly in terms of source integration, citation, and referencing.

| What positive aspects of your past assignments do you want to demonstrate in your next assignment?

Source integration, citation, and referencing (areas for improvement): Which three source integration, citation, or referencing issues do you intend to address when writing your next assignment? Record your responses below. In addition, locate pages in your textbook that will help you address these issues, and record the pages below.

Issue 1:

Issue 2:

Issue 3:

|

Homework: Reflect on Your Course Performance in a Letter

Consider the outcomes for your writing course(s) in relationship to your writing efforts this semester, and write a block-formatted letter to your instructor in which you address the items listed below. Remember to cite and reference any outside sources of information that you use.

- To what level have you achieved each outcome, and what evidence can you offer to support your claims?

- Identify one or more writing skills you would like to continue to work on in the future.

Consult the “Organizing Paragraphs” and “Writing Print Correspondence” chapters of this textbook for guidance when writing and formatting your letter. You might use the pre-writing strategies listed in the current chapter to develop ideas for your assignment.

Your writing instructor might also use the following prompts during class time as preparation for the assignment. Alternatively, you can use the prompts to think about your own performance.

- Discuss how successful you have been in achieving the course outcomes with a small group of students in your class. What specific evidence from your writing assignments can you offer as evidence for your claims?

- Discuss with your group members what you actively did to ensure your own success in the course.

- Did you establish interim deadlines or sub-goals for yourself when working on assignments? If so, how did you keep track of these?

- Did you produce assignments in line with given criteria and directions? If so, how did you accomplish this goal?

- Did you use instructor/peer feedback to improve performance? If so, how?

- Did you meet with your instructor to resolve questions? How often?

- Did you visit with tutoring, library, advising, counselling, or other academic support staff?

- Discuss with your group members how the writing you did in this course affected your development as a writer.

- How does your writing in this course compare with writing you did in the past?

- What do you know now that you did not know before taking this course?

- What can you do now that you could not do before taking this course?

- Discuss with your group members areas for further development in terms of writing skills. Which skills do you intend to work on in the future? How will you address them?

- Discuss with the whole class how you intend to use responses to the in-class prompts to develop your reflection letter.

When you have drafted your letter, consult the handouts below—“Making Sense of Colons” (Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo, n.d.a) and “Making Sense of Semi-Colons” (Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo, n.d.b)—to ensure you have used these marks of punctuation correctly in your text.

Making Sense of Colons

A colon is a form of punctuation used at the end of a complete sentence to introduce a list or quotation, offer an explanation, or highlight information. It prepares the reader for the information that comes after it.

Colons and independent clauses

A colon can join two complete sentences (independent clauses) when the second clause is connected to the first in terms of content. Capitalization of the first word in the second sentence varies according to the style manual used.

e.g., Exercise improves cognitive function in one key way: It promotes the growth of new brain cells, thereby enhancing performance on memory tasks.

In the above example, the sentence after the colon (starting with “it promotes…”) offers an explanation of the “key way” identified in the first sentence. It clarifies the original sentence.

Helpful tip: colons cannot be used when the writing before the colon is not an independent clause, as in the following sentence:

My favourite foods are: sushi, pizza, and nachos.

Colons and emphasis/explanation

A colon follows a complete sentence when introducing a list or quotation, offering an example or explanation, or emphasizing a point.

- Participants responded to the survey on three occasions: baseline, pre-treatment, and post-treatment.In the above example, the list after the colon clarifies the “three occasions” mentioned before the colon.

- Mark Twain said it best: “Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.”In the above example, Mark Twain’s quotation is provided after the colon.

- Many participants indicated there was a positive outcome of exercising daily: reduced symptoms of anxiety.In the above example, what follows the colon (“reduced symptoms of anxiety”) clarifies the “positive outcome” mentioned before the colon.

Helpful tip: another common use of the colon is to separate a title from a subtitle.

e.g., Star Wars: The Force Awakens

Making Sense of Semicolons

The semicolon is a useful form of punctuation for connecting closely-related ideas in a sentence, usually in the form of independent clauses. It allows the reader to identify ideas or claims that are connected to each other.

How to use semicolons

There are a number of ways to use a semicolon grammatically; stylistically, however, it is most effective when used sparingly to perform the following tasks:

- Connect two independent clauses of equal grammatical rank -OR-

- Separate items in complicated lists

Semicolons and two independent clauses with no transitions

A semicolon is used to link two independent clauses when the ideas in the two clauses are closely related, and there is no coordinating conjunction (and, or, but). The following sentence is an example of this structure:

e.g., Some students write down everything said in class; others take down only the key points.

Semicolons and two independent clauses with transitions

A semicolon is used between two independent clauses that are linked by a transition word or expression. The following sentence is an example of this structure:

e.g., Mark took a French course during the summer; however, at the end of the course, he still couldn’t understand French.

Helpful tip: A transition word or expression links words, phrases, or clauses to connect ideas smoothly.

e.g., for example, as a result, in addition, in fact, on the contrary, however, similarly, consequently

For more information, see our learning resource on transition words.

Semicolons and complex lists

A semicolon is used between items in a complex list or series, especially when the items already contain commas. The semicolon allows the reader to recognize major groupings of words. The following example lists three detailed topics covered in a course:

e.g., Students in this course will study the historical, digital, and economic origins of maker culture; the practical, philosophical, and gender resistance to the movement; and the technological and political ramifications others might not have considered.

Helpful Tip: except for lists, asking “could I put a period in place of the semicolon?” is an easy way to identify whether your semicolon use is appropriate. If the answer is “yes,” you are probably using it correctly.

References

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020). Argumentative portfolio letters. License: CC-BY 4.0. https://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/argument-and-digital-writing/argument-and-digital-writing-argumentative-portfolio-letters/

Kirk, K. (2017, June 8). The cycle of self-regulated learning [Figure]. Supporting and Advancing Geoscience Education at Two-Year Colleges. License: CC-BY-SA 3.0. https://serc.carleton.edu/sage2yc/self_regulated/what.html

Nobel, C. (2014, May 5). Reflecting on work improves job performance. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/reflecting-on-work-improves-job-performance

SAGE 2YC. (2017, June 8). What is self-regulated learning?. License: CC-BY-SA 3.0. https://serc.carleton.edu/sage2yc/self_regulated/what.html

Wilfrid Laurier University. (n.d.). Reflective writing, section D: Writing a reflection. WriteOnline.ca. License: CC-BY-NC. http://writeonline.ca/reflective-essay.php?content=section4

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.a). Making sense of colons. License: CC-BY-SA 4.0. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/making_sense_of_colons_0.pdf

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.b). Making sense of semicolons. License: CC-BY-SA 4.0. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/making_sense_of_semicolons.pdf