Using Resources Effectively

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

This chapter aims to help you understand what study support resources are available to college students and how to use them effectively. Although colleges offer a variety of academic support resources for students, this chapter will focus specifically on meetings with instructors, writing tutors, and librarians since many students have access to these offerings. It will also discuss reflection as a personal learning tool you can use to enhance your university experience.

Adjusting to the Challenges of College Life

College life can be challenging for a number of reasons. You may be learning how to manage demands upon your time; how to budget for expenses; how to balance school, work, and home responsibilities; how to study in a another language; how to navigate the financial aid process; how to complete coursework when you have a disability or learning difficulty; or how to readjust to civilian life after military service. Although these challenges can be substantial, they do not have to be insurmountable—indeed, colleges want to see students succeed and, consequently, offer a number of resources that can help in this regard.

Although colleges provide vital support resources, many faculty and staff believe that students are responsible for accessing them because college also provides an opportunity to demonstrate personal accountability. Ultimately, you must take active steps in college to help ensure your own success, which means that you may have to actively seek out available support services rather than expect support personnel to come to you. To fully benefit from support resources, aim to use them effectively by taking into account the tips provided in this chapter.

Meeting with an Instructor

College instructors reserve space in their weekly schedules for office hours, or open periods of time available for meeting or communicating with students. Although the length of office hours may vary by instructor, course, and institution, instructors generally offer one office hour per week for each course they teach. Since the instructors dedicate these time periods solely to students, office hours may be thought of as a vital study support mechanism that, if used effectively, can help students meet their academic goals.

To fully benefit from an instructor’s office hours, it is best to prepare in advance before a meeting. You must first find out when and where an instructor’s office hours are scheduled. Instructors typically post these times on their syllabuses, their office doors, or both, and some also announce the hours in class. Be sure to ask an instructor if you are not sure when he or she has office hours. In terms of location, oftentimes this will be an instructor’s office or another campus space; however, if you are taking an online course, the instructor may arrange to communicate with you via email, phone, a learning management system, or through an online conferencing application such as Skype or Zoom. Regardless of office hour logistics, the following tips should help you prepare for a meeting.

- Think about your goal(s) for the meeting. In other words, what do you want to achieve from the meeting?

- Write up a list of questions or points to discuss with your instructor while keeping your goal(s) in mind. Do not plan to simply ask an instructor how you can achieve a high grade because many factors can impact a student’s grade in a course; instead, write specific course- or assignment-related questions or points on your list.

- Prioritize the items on your list in order of importance in case the instructor has limited time during the meeting.

- Gather any materials you might need for the meeting, such as paper for making notes, a pen or pencil, your list of questions, and your textbook(s). If you plan to ask the instructor questions about a homework or writing assignment, gather that material as well.

Sometimes instructors will advise students to bring specific things with them to office hour meetings. In these cases, be sure to bring what the instructor requests. Figure 1 presents an example document that an instructor might give a student to help structure an office hour meeting so that it is maximally productive.

Directions: Review the feedback on your last written assignment prior to our meeting. Identify three feedback points that you wish to discuss, and provide ideas for how you might address them in future assignments.

1.

2.

3.

Figure 1. An example task that an instructor might ask a student to complete for a meeting

In addition to preparing materials prior to a meeting with an instructor, you should also plan to take notes during the meeting to record important points for future reference.

Along with office hour meetings, some writing instructors also schedule individual conferences with students to discuss plans for or drafts of papers. If your instructor does this, make full use of the conference as a learning opportunity by preparing for it in advance. Bear in mind that a conference presents a chance to interact with an instructor on an individual basis: if you have been hesitant to share your views or questions in class, a conference allows you time to do so away from your peers.

Some instructors provide structured guidance to help students prepare for conferences. Figure 2 provides an example of a conference preparation form that an instructor might give a student in advance of conference. The instructor would likely ask the student to complete the form and bring it to the conference, again to ensure the meeting is maximally productive.

Conference Preparation Form

1. What is your working thesis statement (one or two sentences that identify your topic + your position on the topic)?

2. What three sources will you potentially use in your assignment? Record APA references for the sources below.

3. How did you assess the credibility of your chosen sources?

4. How will you use the sources in your assignment?

5. Read the feedback on your previous assignments. Based on this feedback, what three action points would you like to focus on in your next assignment?

6. What, specifically, do you intend to do to address the action points listed in number five?

7. Do you have any questions for the instructor? If so, record these below.

Figure 2. A sample conference preparation form

If your instructor does not provide a conference preparation form, you can still prepare before the conference by completing the bullet-point steps listed previously in this chapter.

As a final note, by preparing for a meeting with an instructor, you can demonstrate that you are engaged in a course, that you wish to get as much as you can out of the course, and that you respect your instructor’s time.

Meeting with a Writing Tutor

If your campus offers face-to-face or online tutoring appointments, think of these as opportunities to refine your coursework outside the classroom. Some campuses arrange group tutoring sessions, while others offer one-on-one meetings with tutors; regardless of the configuration, think of a tutoring session as a vital resource that, if used wisely, can pay valuable dividends in terms of your academic success.

Writing tutors can generally help students with different phases of the writing process, including planning, organizing, and revising papers. A tutor is unlikely to edit a paper since that responsibility falls on the student, but a tutor can offer suggestions that may help improve the paper. To fully benefit from a tutoring session, prepare for it in advance by taking the following steps.

- Make a note of the time and place for the tutoring session on your calendar or weekly planner.

- Consider what you want to achieve during the session and what questions will help you in this effort.

- Write down the questions or points you wish to discuss with the writing tutor. Do not plan on asking the tutor how you can achieve a high grade on your paper since different factors can affect a student’s grade on an assignment. Instead, list specific questions that relate to the paper you are working on; if you have reviewed your feedback on previous assignments, you might have questions, for instance, about how to apply certain aspects of the feedback to your current paper.

- Prioritize the items on your list in order of importance so that you can address the most pressing ones first.

- Gather all the things you will need for the session: notepaper and something to write with, a copy of the assignment directions and grading specifications, a copy of your draft paper or assignment plan (if you are in the organizing stage of writing), and your textbook(s).

On the day of your tutoring appointment, be sure to check in on time with the tutor and have your preparation materials handy. When asking questions or raising discussion points, take notes on what the tutor says so you can refer to them later as needed, and if you need clarification on a certain point, do not be afraid to ask.

When working with a writing tutor, remember that constructive criticism can actually help strengthen your papers and that most professionals, regardless of the jobs they perform, receive feedback on their work from various stakeholders (people with an interest in what they do). In brief, constructive criticism may identify what needs to be changed in a paper, why it needs to be changed, and how it can be changed. Alternatively, constructive criticism can highlight what works well in a paper, why this is the case, and how the positive aspect affects the reader—a particularly important consideration in technical writing since it strives to be reader focused. Regardless of the feedback you receive during an appointment with a writing tutor, examine it carefully to determine how you might apply it to your current or future assignments. And if you need further explanation to understand a feedback item, ask the writing tutor so that your session is productive.

Meeting with a Librarian

In addition to the resources this chapter has discussed thus far, librarians can also support students’ efforts to be successful in college. For instance, librarians can help students locate books and other materials for course projects; evaluate the trustworthiness of sources; cite and reference sources in adherence with style guidelines; identify what types of sources various materials are; and use databases, which are expansive, online collections of curated works that can be navigated via use of keywords.

When asking a librarian for assistance with a project, prepare in advance by using the following guidance to help ensure you gain the maximum benefit from the interaction.

- Prepare a list of specific questions or points for discussion with the librarian. If you wish to see how a library resource, such as a database, works, then plan to ask the librarian for a demonstration or a set of instructions.

- Arrange your questions or points in order of importance so that you can address the most critical ones first.

- Gather together any materials you will need when speaking with the librarian, such as a copy of your assignment or assignment plan, a copy of the assignment directions, and a pen and paper.

- Plan to take notes during your conversation with the librarian to record important points for future reference.

Although some librarians may only see students by appointment, others will be freely available to help students during library service hours. Check with your college library or its website to determine the protocol for your institution.

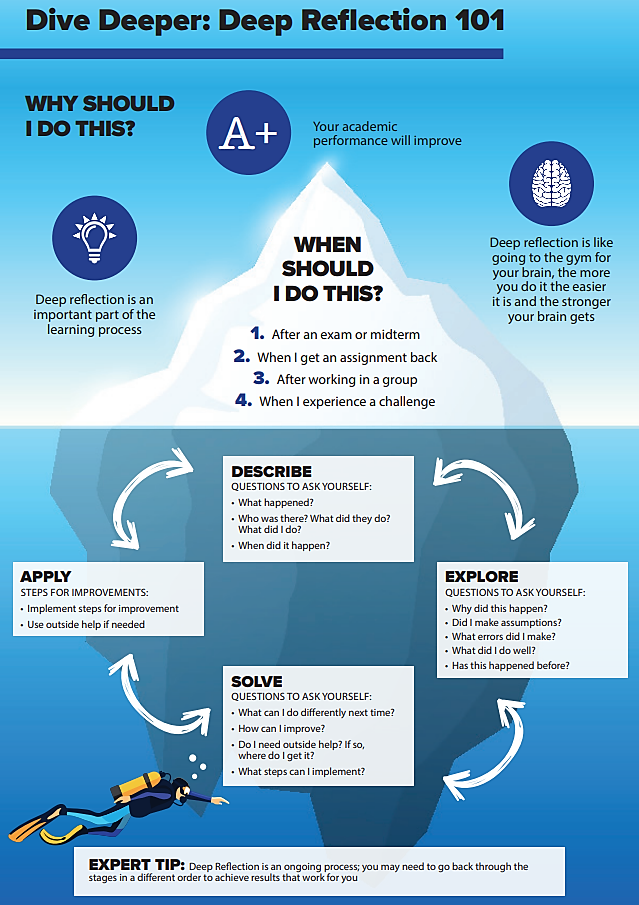

Reflecting on Your Experiences in College

As you use the study support resources mentioned in this chapter, or indeed anytime you engage in a learning opportunity in college, remember to reflect on the experience to gain long-lasting benefit from it. Reflection is a cyclic process whereby you

- Prepare for an experience by establishing goals and strategies.

- Engage in the experience while using the strategies.

- Discover the results of your efforts and think carefully about what they mean in terms of your aspirations.

- Use the results to devise goals and strategies for the next similar experience.

The reflection process can help to reveal productive and less-than-productive strategies and how these affect growth and advancement; it can also help you identify areas for further development and discover your own role in your college success. Figure 3, from McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph (n.d.), under a CC-BY-SA license, illustrates the reflection process at work.

Figure 3. Use the reflection process to improve your college experience

As Figure 3 articulates, reflection is a continuing process, one that will serve you well throughout academia and beyond.

In addition to the benefits of reflection already mentioned, reflecting on college experiences can also lead to enhanced resilience: as you deconstruct the factors that led to a certain result and come to understand the relationship between your thoughts, actions, and successful and unsuccessful experiences, you may determine what it takes to persevere with your work. The following vignette, adapted from The Learning Portal, College Libraries Ontario (2020, “Strategies for Coping with Problems: Passive vs. Active”), demonstrates this point with a true-to-life example.

Example: Coping with Problems

Miriam takes a midterm exam for a class and scores a failing grade. She studied hard, so she’s surprised and disappointed she did so poorly. Blinking back tears, Miriam takes a few deep breaths while looking over her test.

With her academic and professional aspirations in mind, Miriam now has a crucial decision to make: she can (1) ignore the situation, (2) blame the instructor for the situation, or (3) reflect on the situation and take active steps to help effect a different result on the final exam. Miriam thinks to herself, I’ve used the first two coping strategies in the past and only wound up frustrated and bitter. I better try something else.

After class, she’s still feeling pretty upset, so she goes for a run—she knows that always makes her feel better. Plus, it gives her a chance to contemplate what happened on the exam. When Miriam gets home, she emails her professor, asking him for a meeting to get more feedback on her midterm. This way, she can figure out what specific content she is misunderstanding and how she can improve.

In the end, Miriam decides to use reflection to determine a way forward and takes constructive action to improve future outcomes.

As the positive results of the reflection process trace their effects on our actions, resilience can follow as we learn productive mechanisms for advancing toward goals, even in the face of challenges.

Chapter Wrap-Up

Take active steps to help ensure your own academic success by using the resources and tools identified in this chapter to meet the challenges of college life.

Activity A: Delve Further into the Benefits of Office Hours

Listen to a podcast that aired on National Public Radio entitled “Uncovering a Huge Mystery of College: Office Hours” (Nadworny, 2019), which can be found at https://www.npr.org/2019/10/02/766568824/uncovering-a-huge-mystery-of-college-office-hours, and work in pairs or small groups to complete the following items.

- What do you think of the ideas presented in the podcast? Which do you agree with, and why? Which do you disagree with, and why?

- How might you use the ideas discussed in the podcast to your advantage in college?

- Share your group’s ideas with the class.

Activity B: Consider How to Address Situations that Arise in College

Consider the situations listed on the table, and work with a partner to decide what or who can provide the information needed to address them. Complete the items on the table while consulting course and institutional resources as necessary for answers; do not automatically assume that your instructor can provide help with all of the situations. After you have completed the items already listed, work together to brainstorm other situations to add to the list, and complete the table for those items. The situations might be ones you have already experienced. Be prepared to share your ideas with the class and to listen for useful items to add to your table. Once completed, your table will provide a quick reference guide as you proceed through your studies. This activity is adapted from Learn Higher (2019).

| Situation | What/Who Can Provide the Information |

|---|---|

| I need to know where the library is | Campus map |

| I have problems formatting references | |

| I don’t know how to complete an assignment | |

| I don’t know when an assignment is due | |

| I need to know when and where class meets | |

| I need to know when the library is open | |

| I’m not sure when to use commas | |

| I don’t know when the semester ends | |

| I don’t know if an ATM is located on campus | |

| I need help planning a paper | |

| I would like to read a course description before enrolling in a class | |

| I’m not sure how my assignment is being graded | |

| I need to know when my instructor has office hours | |

| I found a source for my paper but am not sure how to determine whether it is credible |

Homework: Email Your Instructor about the Chapter and Campus Resources

Read an essay entitled “Why Visit Your Campus Writing Center?” (Rafoth, 2010) at https://wac.colostate.edu/books/writingspaces1/rafoth–why-visit-your-campus-writing-center.pdf; this essay discusses the value of meeting with a writing tutor. Afterwards, compose an email to your instructor in which you address the questions listed below. Use standard conventions for professional emails when completing this task, and cite and reference any outside sources of information that you use.

- What did you find to be the most interesting, thought-provoking, or unusual idea(s) presented in the essay?

- What campus resources will you use to help ensure your own success in your writing course(s)? Refer, as needed, to the essay, current chapter, and radio program mentioned in Activity A.

Consult the “Writing Electronic Correspondence” chapter of this textbook for guidance when composing and formatting your email.

Remember to edit, revise, and proofread your message before sending it. The following multipage handout, produced by the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d.), may be particularly useful when considering the correct placement of commas in your message.

Making Sense of Commas

A comma is a form of punctuation used to separate distinct elements in a sentence, including listed items, dependent and independent clauses, transition words and phrases, and non-essential information.

Commas in a list

Use commas to separate items in lists of three or more items.

e.g., I’m studying Italian, Computer Science, Statistics, and Functions.

Commas and introductory phrases

Commas are used after short introductory phrases. A comma indicates that the introductory information is over, and the main part of the sentence is beginning. Introductory phrases may include context about times or dates. They may also be transition words or phrases.

e.g., In 1949, Newfoundland joined Confederation.

e.g., However, many citizens remained loyal to the idea of independence.

Grammatical Tip: use two commas for transition words used in the middle of the sentence.

e.g., Most of Smith’s conclusions, however, are valid.

Commas and coordinating conjunctions

Commas generally come before coordinating conjunctions that join independent clauses.

e.g., I was failing Calculus, so my parents hired a tutor.

e.g., Students today must be better prepared than ever, for competition in the workplace is fierce.

Grammatical Tip: the coordinating conjunctions can be remembered through the acronym F.A.N.B.O.Y.S.

-

F – FOR

-

A – AND

-

N – NOR

-

B – BUT

-

O – OR

-

Y – YET

-

S – SO

Commas and parenthetical expressions

A parenthetical expression adds secondary or supplemental information to a sentence. Placing commas around this information indicates that the information is non-essential from a grammatical standpoint and could be removed without interfering with the overall meaning or structural completeness of the sentence.

e.g., My PSYCH 345C textbook, which costs over $175, is difficult to understand.

e.g., Marjorie, Don’s wife of thirty years, planned a surprise party for his 75th birthday.

Grammatical Tip: commas used for parenthetical expressions can also be replaced by dashes or, occasionally, parentheses.

Commas and complex sentences

Complex sentences are ones that contain one independent clause (complete sentence) and one or more dependent clauses. Whether or not you use a comma depends on the order in which the clauses are presented.

- Use a comma when a dependent clause is followed by an independent clause.e.g., Because the course was so popular, the department decided to run extra sections in the fall.

- Do not use a comma when an independent clause is followed by a dependent clause.e.g., The department decided to run extra sections of the course in the fall because it was so popular.

General Tip: while the guidelines in this handout are designed to help you understand and use commas correctly, it is important to note that there will be exceptions to these rules for stylistic or flow purposes. For example, the following sentence is grammatically correct based on comma rules, but it has so many commas in a short space that the sentence may appear disjointed:

e.g., She should be here at 9, but, if not, we can start anyway.

The above sentence might be written to omit the second comma. Be careful, since some people may judge this as grammatically incorrect. However, it is a common construction when a parenthetical expression (if not) directly follows a coordinating conjunction (but):

e.g., She should be here at 9, but if not, we can start anyway.

References

Learn Higher. (2019). Getting yourself informed. License: CC-BY-SA 3.0. http://www.learnhigher.ac.uk/learning-at-university/time-management/getting-yourself-informed/

The Learning Portal, College Libraries Ontario. (2020). Tackling problems. https://tlp-lpa.ca/study-skills/tackling-problems

McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph. (n.d.). Dive deeper: Deep reflection 101. License: CC-BY-SA. https://learningcommons.lib.uoguelph.ca/item/dive-deeper-deep-reflection-101

Nadworny, E. (Host). (2019, October 2). Uncovering a huge mystery of college: Office hours [Audio podcast episode]. In All things considered. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2019/10/02/766568824/uncovering-a-huge-mystery-of-college-office-hours

Rafoth, B. (2010). Why visit your campus writing center? In C. Lowe, & P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings on writing (Vol. 1, pp. 146-155). Parlor Press. License: CC-BY-NC-ND. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/writingspaces1/rafoth–why-visit-your-campus-writing-center.pdf

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Making sense of commas. License: CC-BY-SA 4.0. https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/making_sense_of_commas_1.pdf