1 Developing Study Skills

Dr. Karen Palmer

Balancing College, Work, and Life

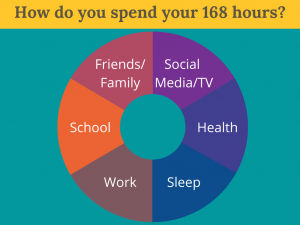

Attending classes, studying, working, and finding time for family, friends, and yourself can be a challenging schedule for college students to balance. How a student organizes their class load can affect their overall success when starting college. We cannot go back in time. If I used my time poorly last Wednesday, I can’t get it back.

“If you had a bank that credited your account each morning with $86,400, but carried no balance from day to day and allowed you to keep no cash in your account, and every evening cancelled whatever part of the amount you had failed to use during the day, what would you do? Draw out every cent, of course! Well, you have such a bank, and its name is time. Every morning it credits you with 86,400 seconds. Every night it writes off as lost whatever of these you have failed to invest to good purpose. It carries no balance; it allows no overdrafts. Each day it opens a new account with you. Each night it burns the record of the day. If you fail to use the day’s deposit, the loss is yours. There is no going back. There is no drawing against the morrow. You must live in the present – on today’s deposit. Invest it so as to get the utmost in health and happiness and success.”

– Anonymous

Most of us spend our time doing a combination of what interests us, what’s important to us, and what we feel we “have” to do, without really planning out our day. As a college student, it’s important to find better ways to spend your time, allowing you to accomplish your most important tasks and spend time with the people most important to you.

Knowing how many hours are in a week helps when we start to look at how much time we have, how we want to spend our time, and how we actually spend our time. The following list includes many activities that might fill your time:

- Child Care

- Class

- Community Service / Volunteer

- Commuting / Transportation

- Eating / Food Preparation

- Exercise

- Family

- Friends

- Household / Child Care Duties

- Internet / Social Media / Phone / Texting

- Party

- Recreation / Leisure

- Relationship

- Sleeping

- Spirituality / Prayer / Meditation

- Study

- Video Games

- Watching TV or Movies, Netflix, Youtube

- Work / Career

It can be helpful to keep track of the time you spend doing different activities for a week or two. You might be surprised how much time is wasted on social media, TV, and other activities that are not helping you achieve your goals.

Transition from a High School to a College Schedule

One challenge for many students is the transition from the structure of high school to the structure of college. In high school, students spend a large portion of their time in class (approximately 30 hours per week), while full-time college students may spend only one-third of that time in class (approximately 12 hours per week).

Further, college students are assigned much more homework than high school students. Think about how many times one of your high school teachers gave you something to read during class. In college, students are given more material to read with the expectation that it’s done outside of class. In fact, college students should plan to spend about 2-3 hours studying each week for every 1 credit hour. So, if you are taking 12 credit hours, plan on a total of 48 hours a week spent on reading, studying, homework, and attending class.

You might need to spend more time than what is recommended if you are taking a subject you find challenging, have fallen behind in a class, or if you are taking short-term classes. This would certainly be true if I were to take a physics class. Since I find learning physics difficult, I might have to spend three or four hours of study time for each hour of class instruction. You also might need to study more than what is recommended if you are looking to achieve better grades. Conversely, you might need to spend less time if the subject comes easy to you (such as sociology does for me) or if there is not a lot of assigned homework.

Keep in mind that 20 hours of work per week is the maximum recommended for full-time students taking 12 semester units in a term. For students working full-time (40 hours a week), no more than six units is recommended. The total of both combined is an important consideration. Students often start to see difficulty when their total number of hours between work and school exceeds 60 per week. The amount of sleep decreases, stress increases, grades suffer, job performance decreases, and students are often unhappy.

“Lack of direction, not lack of time is the problem. We all have 24 hour days.”

– Zig Ziglar

Creating SMART Goals

The universal challenge of time is that there are more things that we want to do and not enough time to do them. Most students have aspirations, dreams, and goals, and they are in college to help them achieve those goals. However, many students get discouraged by the length of time it takes them to complete a goal (completing their education, reaching their career goal, buying a home, getting married, etc.). And every semester there are students who drop classes because they have taken on too much or they are unable to keep up with their class work because they have other commitments and interests.

There is nothing wrong with other commitments or interests. On the contrary, they may bring joy and fulfillment, but it’s important to think about whether those other interests are helping you achieve your goals…or keeping you from them. For instance, if you were to drop a class because you required surgery, needed to take care of a sick family member or your boss increased your work hours, those may be important and valid reasons to do so. On the other hand, if you were to drop a class because you wanted to binge watch Grey’s Anatomy, play more Minecraft, or spend more time on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, you may have more difficulty justifying that decision. Regardless, this is still your decision to make. Whether or not you achieve your goals is ultimately up to you.

Without goals, we aren’t sure what we are trying to accomplish, and there is little way of knowing if we are accomplishing anything. If you already have a goal-setting plan that works well for you, keep it. If you don’t have goals, or have difficulty working towards them, I encourage you to try this.

Make a list of all the things you want to accomplish for the next day. Here is a sample to do list:

- Go to grocery store

- Go to class

- Pay bills

- Exercise

- Social media

- Study

- Eat lunch with friend

- Work

- Watch TV

- Text friends

Your list may be similar to this one or it may be completely different. It is yours, so you can make it however you want. Do not be concerned about the length of your list or the number of items on it. You now have the framework for what you want to accomplish the next day. Hang on to that list. We will use it again.

Now take a look at the upcoming week, the next month and the next year. Make a list of what you would like to accomplish in each of those time frames. If you want to go jet skiing, travel to Europe, or get a bachelor’s degree: Write it down. Pay attention to detail. The more detail within your goals the better. Ask yourself: what is necessary to complete your goals?

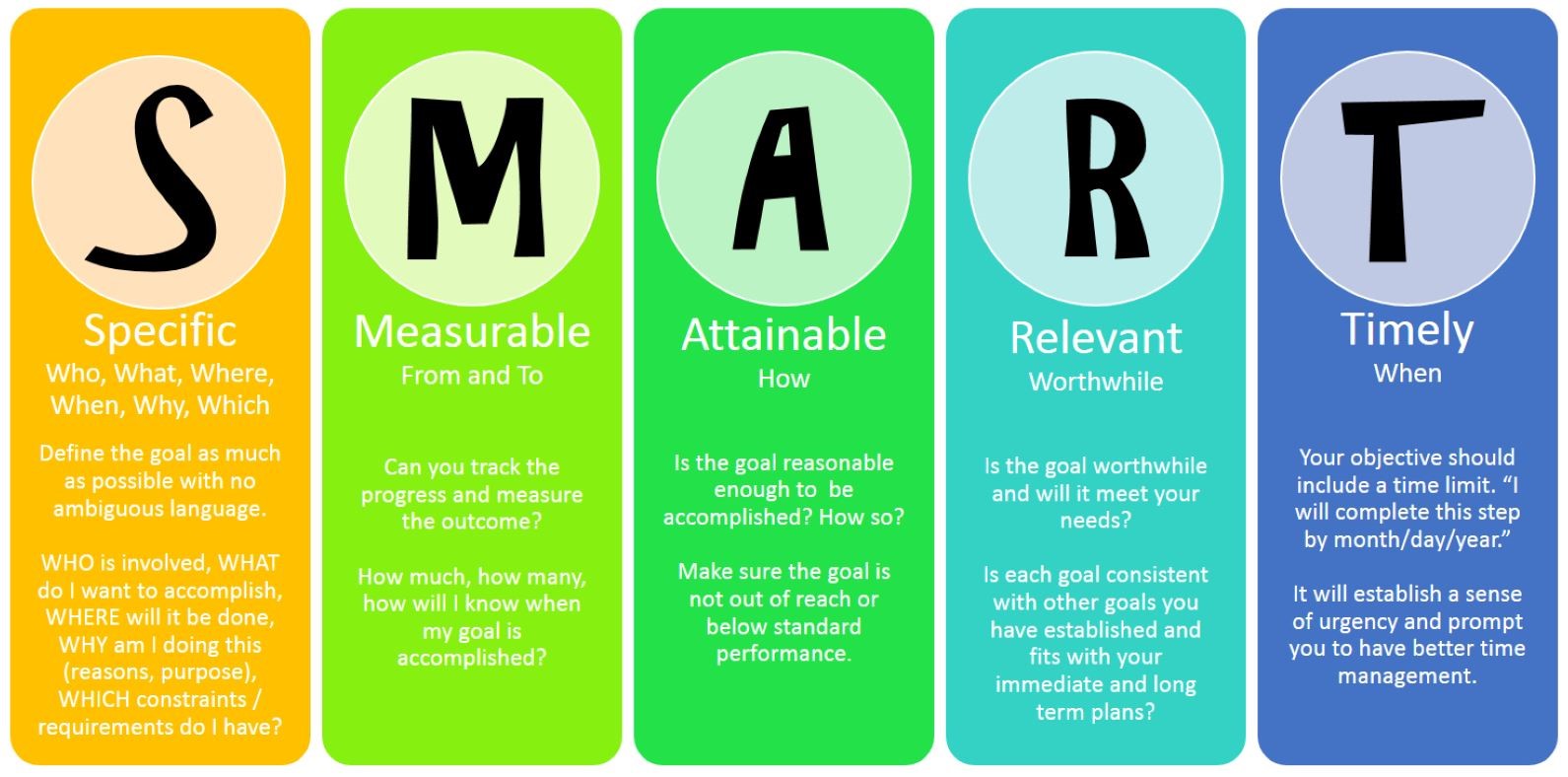

With those lists completed, take into consideration how the best goals are created. Commonly called “SMART” goals, it is often helpful to apply criteria to your goals. SMART is an acronym for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time Based.

Revise your lists for the things you want to accomplish in the next week, month, and year by applying the SMART goal techniques. The best goals are usually created over time and through the process of more than one attempt, so spend some time completing this. Do not expect to have “perfect” goals on your first attempt. Also, keep in mind that your goals do not have to be set in stone. They can change. And since over time things will change around you, your goals should also change.

“Obstacles are things a person sees when he takes his eyes off his goal.”

– E. Joseph Cossman

Exercise 1

If you decided today that our goal was to run a marathon and then went out tomorrow and tried to run one, what would happen? Unless a person is already a trained marathon runner, we might respond with: (jokingly) “I would die,” or “I couldn’t do it.” How come? Because we likely need training, running shoes, support, knowledge, experience, and confidence—all things that cannot be attained overnight. Instead of giving up and thinking it’s impossible because the task is too big for which to prepare, we could develop smaller steps or tasks that can be started and worked on immediately. Once all of the small steps are completed, we would be on our way to accomplishing this big goal.

What steps would you need to complete the following big goals?

- Buying a house

- Getting married

- Attaining a bachelor’s degree

- Destroying the Death Star

- Losing weight

Time Blocking

Once you’ve thought through what goals you want to accomplish and how much time you have to accomplish them, it’s time to make a plan. Many professionals use a concept called Time Blocking to help them manage their time in a way that will help them achieve their goals. Time blocking is a way to create a schedule by assigning chunks of time in the day/week/month/year to work on different tasks.

Sometimes it helps to take a look at your time and divide it into two areas: fixed time and free time. Fixed time is time that you have committed to a certain area. It might be school, work, religion, recreation, or family. There is no right or wrong to fixed time, and everyone is different. Some people will naturally have more fixed time than others. Free time is just that—it is free. It can be used however you want to use it; it’s time you have available for activities you enjoy. Someone might work 9am-2pm, then have class 3pm-4:30pm, then have dinner with family 5pm-6pm, study 6pm-7pm, and then have free time from 7pm-9pm. Looking at how we spend our time often shows us that we have more time than we think we do…or reveals how much time we spend on activities that do not help us to achieve our goals!

Once you have a solid idea of how much time you have in your day, it’s easier to make time for activities that aren’t fixed, like studying. It’s a really good idea to set up a fixed time each day when you plan to study for your classes.

Exercise 2

Take a look at a typical week for yourself. Use the table below to fill in the your fixed time activities. Set the times in the left column to correspond to the hours between when you wake up and when you go to sleep. How much fixed time do you have? How much free time? How much fixed and free time would you like to have?

| Time | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

Using Time Wisely

Once you have a basic idea of how you want to use your time, it’s easier to use your time wisely. However, there are times when you might have more on your “to do” list than normal, and it may feel like you just can’t accomplish everything. In times like these, you might stress out, you might procrastinate even more, you might even simply want to give up. None of these options will help you to achieve your goals. So, having a strategy to deal with that situation before it arises can help you to make better choices in the moment.

Creating a list is a good way to get started. Having everything you have to do in front of you gives you the opportunity to prioritize and make wise decisions instead of simply doing the easiest or quickest tasks. For example, checking Facebook or texting might only take a few minutes, but doing it prior to studying for a test means that you might end up having less time than you need to study.

People like to check things off that they have done. It feels good. But don’t confuse productivity with accomplishment of tasks that aren’t important. You could have a long list of things that you completed, but if they aren’t important to you, it probably wasn’t the best use of your time.

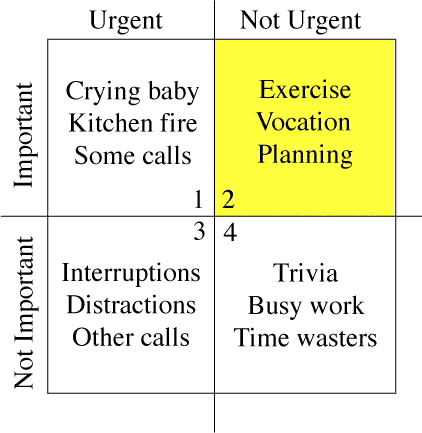

A Time Management Matrix can help you categorize your tasks. Thinking through whether each task is urgent and important will help you to prioritize what should be done first. Start with tasks that are both urgent and important, then move on to those that are important, but not urgent. Deal with tasks that are not important, but urgent quickly. Leave unimportant, non-urgent tasks for last.

Image by Rorybowman – Public Domain

Exercise 3

Here is one student’s “to do” list on Sunday evening:

ENG-Revise paper–due Friday

Call Mom

Do laundry

MAT-finish homework, due Monday

Psych-Read Chapter 3 before class on Tuesday

SPA-Extra Credit assignment due by the end of the semester

Buy groceries

Apply for scholarship–due in two weeks

Pay phone bill–due Wednesday

Categorize the tasks into the four quadrants using the table below:

Taking Notes

If for no other reason, you should take notes during class so that you do not forget valuable and important information. Despite living with incredible search engines on computers and smart phones that give us a plethora of information 24 hours a day, seven days a week, students do not have the ability to access those during exams. Instructors want to know what you know, not what Google knows. We’ve become accustomed to searching for information on demand to find what we need when we need it. The consequence is that we don’t often commit information to memory because we know it will be there tomorrow if we wish to search for it again. This causes challenges with preparation for exams as what we’re tested on is in our brain rather than information we can search for.

The curve shows that after six days, only about 25% percent of information is retained after initial memorization. Without review, 42 percent of learned information is lost after only 20 minutes. After one day, 66 percent of learned information is lost without review.

In order to try to retain information long term, we must move it from our short-term memory to our long-term memory. One of the best ways to do that is through repetition. The more we review information, and the sooner we review once we initially learn it, the more reinforced that information is in our long-term memory.

The first step in being able to review is to take notes when you are originally learning the information. Students who do not take notes in class in the first place will not be able to recall all of the information covered in order to best review.

Taking notes during lectures is a skill, just like riding a bike. If you have never taken notes while someone else is speaking before, it’s important to know that you will not be an expert at it right away. It’s challenging to listen to someone speak and then make a note about what they said, while at the same time continuing to listen to their next thought.

When learning to ride a bike, everyone is going to fall. With practice and concentration, we gain confidence and improve our skill. The more we practice, the better we get. Some instructors will give you cues to let you know something is important. If you hear or see one of these cues, it’s something you should write down. This might include an instructor saying, “this is important,” or “this will be covered on the exam.” If you notice an instructor giving multiple examples, repeating information or spending a lot of time with one idea, these may be cues. Writing on the board or presenting a handout or visual information may also be a cue.

Keep in mind that students who know what their instructor is going to lecture on before the lecture are at an advantage. Why? Because the more they understand about what the instructor will be talking about, the easier it is to take notes. How can you possibly know what the instructor’s lecture will be on? Take a look at the syllabus before the lecture. It won’t take much time, but it can make a world of difference. You will also be more prepared and be able to see important connections if you read your assigned reading before the lecture. It’s not easy to do, but students who do it will be rewarded.

Tips for Taking Notes During the Lecture

- Arrive early and find a good seat. Seats in the front and center are best for being able to see and hear information. A seat at the 50-yard line for the Super Bowl is more expensive for a reason: it gives the spectator the greatest experience.

- Do not try to write down everything the instructor talks about. It’s impossible and inefficient. Instead, try to distinguish between the most important topics and ideas and write those down. This is also a skill that students can improve upon. You may wish to ask your instructor during office hours if you have identified the main topics in your notes, or compare your notes to one of your classmates.

- Use shorthand and/or abbreviations. So long as you will be able to decipher what you are writing, the least amount of pen or pencil strokes, the better. It will free you up so you can pay more attention to the lecture and help you be able to determine what is most important.

- Write down what your instructor writes. Anything on a dry erase board, chalkboard, overhead projector, and in some cases in presentations; these are cues for important information.

- Leave space to add information to your notes. You can use this space during or after lectures to elaborate on ideas.

- Do not write in complete sentences. Do not worry about spelling or punctuation. Getting the important information, concepts, and main ideas is much more important. You can always revise your notes later and correct spelling.

- Often, the most important information is delivered at the beginning and/or the end of a lecture. Many students arrive late or pack up their belongings and mentally check out a few minutes before the lecture ends. They are missing out on the opportunity to write down valuable information. Keep taking notes until the lecture is complete.

Tips for after the lecture

- Consolidate notes as soon as possible after the lecture has ended. Identify the main ideas and underline or highlight them.

- Test yourself by creating questions about the information covered in your notes. If you can provide most of the information in your notes without looking at it, you’re in good shape. If you cannot, keep studying until you improve your retention. Review periodically as needed to keep the information fresh in your mind.

- Practice summarizing information — it’s a great study skill. It allows you to determine how information fits together. It should be written in your own words (don’t use the chapter summary in the textbook to write your summary, but check the chapter summary after you write yours for accuracy).

- Try to share the information you learned with someone else. Teaching is one of the best ways to retain information!

Pre-Test Strategies

is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Q: When should you start preparing for the first test? Circle…

- The night before.

- The week prior.

- The first day of classes.

If you answered “3. The first day of classes,” you are correct. If you circled all three, you are also correct. Preparing to pass tests is something that begins when learning begins and continues all the way through to the final exam.

Many students, however, don’t start thinking about test taking, whether weekly exams, mid-terms, or finals, until the day before when they engage in an all-nighter, or cramming. From the previous unit on memory, you might recall that the brain can only process an average of 5-7 new pieces of information at a time. Additionally, unless memory devices are used to aid memory and to cement information into long term memory (or at least until the test is over tomorrow!) chances are slim that students who cram will effectively learn and remember the information.

Additionally, a lot of students are unaware of the many strategies available to help with the test-taking experience before, during, and after. For starters, take a look at what has helped you so far.

Exercise 4

Pre-Test Taking Strategies

PART A:

Put a check mark next to the pre-test strategies you already employ.

____ Organize your notebook and other class materials the first week of classes.

____ Maintain your organized materials throughout the term.

____ Take notes on key points from lectures and other materials.

____ Make sure you understand the information as you go along.

____ Access your instructor’s help and the help of a study group, as needed.

____ Organize a study group, if desired.

____ Create study tools such as flashcards, graphic organizers, etc. as study aids.

____ Complete all homework assignments on time.

____ Review likely test items several times beforehand.

____ Ask your instructor what items are likely to be covered on the test.

____ Ask your instructor if she or he can provide a study guide or practice test.

____ Ask your instructor if he/she gives partial credit for test items such as essays.

____ Maintain an active learner attitude.

____ Schedule extra study time in the days just prior to the test.

____ Gather all notes, handouts, and other materials needed before studying.

____ Review all notes, handouts, and other materials.

____ Organize your study area for maximum concentration and efficiency.

____ Create and use mnemonic devices to aid memory.

____ Put key terms, formulas, etc., on a single study sheet that can be quickly reviewed.

____ Schedule study times short enough (1-2 hours) so you do not get burned out.

____ Get plenty of sleep the night before.

____ Set a back-up alarm in case the first alarm doesn’t sound or you sleep through it.

____ Have a good breakfast with complex carbs and protein to see you through.

____ Show up 5-10 minutes early to get completely settled before the test begins.

____ Use the restroom beforehand to minimize distractions.

PART B

By reviewing the pre-test strategies, above, you have likely discovered new ideas to add to what you already use. Make a list of them.

Test-Taking Strategies

- Scan the test, first, to get the big picture of how many test items there are, what types there are (multiple choice, matching, essay, etc.), and the point values of each item or group of items.

- Determine which way you want to approach the test: Some students start with the easy questions first, that is, the ones they immediately know the answers to, saving the difficult ones for later, knowing they can spend the remaining time on them. Some students begin with the biggest-point items first, to make sure they get the most points.

- Keep your eye on the clock.

- If you can mark on the test, put a check mark next to items you are not sure of just yet. It is easy to go back and find them to answer later on. You might just find help in other test questions covering similar information.

- Sit where you are most comfortable. That said, sitting near the front has a couple of advantages: You may be less distracted by other students. If a classmate comes up with a question for the instructor and there is an important clarification given, you will be better able to hear it and apply it, if needed.

- Wear ear plugs, if noise distracts you.

- You do NOT have to start with #1! It you are unsure of it, mark it to come back to later on.

- Bring water…this helps calm the nerves, for one, and water is also needed for optimum brain function.

- If permitted, get up and stretch (or stretch in your chair) from time to time to relieve tension and assist the blood to the brain!

Post-Test Strategies

In addition to sighing that big sigh of relief, here are a few suggestions to help with future tests.

- If you don’t understand why you did not get an item right, ask the instructor. This is especially useful for quizzes that contain information that may be incorporated into more inclusive exams such as mid-terms and finals.

- Analyze your results to help you in the future. For example, see if most of your incorrect answers were small things such as failing to include the last step in a math item, or neglecting to double-check for simple errors in a short-answer or essay item. See where in the test you made the most errors: beginning, middle, or end. Also analyze which type of questions, true/false, multiple choice, essay, etc. And which topics were missed. This will help you pay closer attention to those sections in the future.

Attributions

- Content adapted from “Blueprint for Success in College” by Dave Dillon and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Content written by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed CC BY NC SA.