9 Choosing a Topic and Creating an Outline

Dr. Karen Palmer

Brainstorming

Your narrative should start to answer the question “who are you?” However, this story should only focus on one characteristic or aspect of your personality. Think back to Skip and his story. His story helped prove he was ready to be a leader and ready to run a corporation.As with most other types of writing, brainstorming can be a useful tool. To begin, you might just think about all the ways to finish the sentence “I am . . .” The word you choose to finish this sentence then becomes the subject of your narrative. If a subject is not jumping out at you, think about the way your mother, best friend, significant other, or pet might describe you. Think about a characteristic that only the people closest to you see—for example, has anyone ever told you “when I first met you, I never would have guessed that you were so funny (or competitive or happy)”?

Once you have a characteristic in mind, keep brainstorming and think of one specific example or event that illustrates this characteristic. You might think of a story from your life that illustrates the characteristic–or you might remember a person in your life from whom you’ve learned this characteristic. This example will become your story. Again, much like a topic, sometimes an example, or story, will just jump to mind. However, if you cannot think of an example right away, look through some old pictures, scrapbooks, or yearbooks. Reread journals or listen to favorite songs. All of these things can spark memories, and one of these memories can become the example or event on which your narrative will focus. This event does not have to be exciting or flamboyant. Simple but heartfelt stories often are the most effective. Many things can be faked in life, but sincerity is generally not one of them.

Freewriting

Once you’ve chosen a moment, it’s important to take some time to freewrite about this story. Write down what you remember happening. Write about where you were and who you were with. Jot down sensory details. Basically, write down every single thing you can remember–and then start picking and choosing those moments that really powerfully show how this event changed you.

- Ask some questions about the event you are going to write about. When did this event take place? What are the starting and ending points? Where did this event take place? Who was there? Was there a conflict? A resolution? How did you change? Why is this event important to you?

- Write down everything you remember. Of course, there are numerous ways to write a first draft, but for a narrative, simply writing down everything you remember about the event is a good place to start. Usually, it is better to have more writing than what you need. So start by writing everything down in chronological order. Do not worry about any rhetorical strategies or making it sound good. Just write down the entire series of events or actions.

- Go do something else. Once you have the entire story written down, set it aside. Go take a nap or play with your dog, and come back to the story later. Then reread it and see if you left anything out. Time permitting, go through this process of putting the story aside and then rereading it several times.

- Think about your audience. Who will be reading your story? What parts of the story are the most important to portray in order for the audience to understand the message you’re trying to get across?

- Think about your main point. When you’re telling a story, you don’t want to use the exact same formula you might for an academic essay (ie I learned X by going through a, b, and c.) However, you do want to give your readers a statement that indicates what the essay will be about. For example, “Something happened the following Monday that impacted my life forever.” While this statement doesn’t have any spoilers, it does tell readers that something significant happened that has a life-changing effect on the writer. Your thesis might also be an observation about life, people, character, yourself, etc. that you flesh out through the events of your narrative.

Here is a great video created for folks who want to write a book length memoir. Though the speaker is talking about a much larger project than what you will be working on in your composition course, the concepts in this video are very helpful for choosing what the best way to present your story.

Creating Your Outline

Unlike most academic essays, a narrative is not usually organized by the points you are trying to make, but by the chronological events that happen in the story. Your outline should include the major points of the plot in the order they appear.

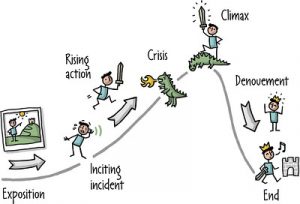

The plot of a story is very simple. The exposition sets up the story. An incident happens that begins the story. Events unfold until a crisis occurs. The crisis is resolved in the climax. The story wraps up in the denouement, and then it ends.

An very simple outline for a narrative might look something like this:

Narrative Outline

- Introduction: Background/Exposition with a statement that provides readers a glimpse at the story’s purpose.

- Inciting Incident

- Rising Action (this could be multiple steps)

- Crisis

- Climax

- Denouement

- Conclusion

___

Attributions:

“Brainstorming” adapted from “Storytelling, Narration, and the Who Am I story” by Catherine Ramsdell. Licensed CC BY NC SA.

“Freewriting” by Dr. Karen Palmer. Licensed CC BY NC SA.

“Freewriting” steps adapted from “Storytelling, Narration, and the Who Am I story” by Catherine Ramsdell. Licensed CC BY NC SA.

“Creating Your Outline” by Dr. Karen Palmer. Licensed CC BY NC SA.