14 The Tested Curriculum and Changing Views of Assessment

“You can enhance or destroy students’ desire to succeed in school more quickly and permanently through your use of assessment than with any other tools you have at your disposal.”–Rick Stiggins

Introduction

Much has been written about the effects of testing on student achievement as it relates to what is taught in the classroom. Some experts believe that society’s mission regarding schools has changed, and so have the reasons for large-scale assessments. Only recently have we begun to look at how assessment and curriculum can work to complement each other by supporting student learning and impacting what is taught in the classroom positively and dynamically.

Essential Questions

- How has society’s mission of its schools changed?

- Has the annual standardized test movement increased student learning?

- How do we help students develop a sense of control over the assessment process?

- What does it mean to have “balance” in assessment?

- Are we measuring what matters in schools?

Assessing Assessments

How has society’s mission of its schools changed and what is the link to assessment? It has been problematic that students who did not do well were not given the skills they needed to be successful in life. In times past, the goal of the assessment was to broaden the gap in student achievement.

The “normal” curve is the clearest example of this thinking: a few students score at the top of the test, most score in the middle, and some fail. Restated, a normal curve assumes that to have a frequency distribution of a normal curve, 50% of the students must score below average and 50% score above.

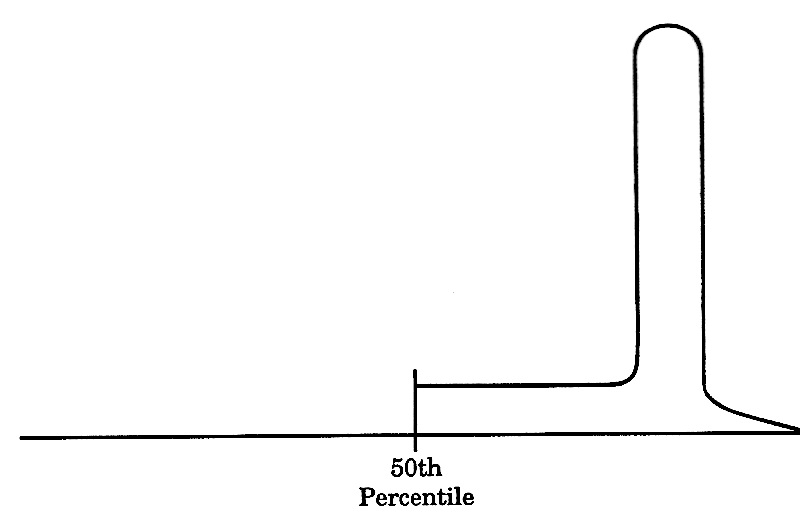

For example, if we randomly sampled 100 individuals, we would expect to see a normal distribution frequency curve for many continuous variables, such as IQ, height, weight, and blood pressure. This may be fine for physical characteristics, but as thoughtful educators, it is important to ask: is it all right to have a goal that relegates some students to failure? (English 2000). Another complicating factor is that test scores are driven largely by socioeconomic factors, so schools that have large populations of lower socioeconomic students are automatically assigned to the “below average” category. This is called “social determinism” based on wealth. English argues that instead of aiming for a normal curve, we should have the “J” curve as a goal. The “J” curve occurs when all the students are learning and “above average.”

Geher (2014) states that the normal distribution is over-applied and over-used. Because few naturally occurring variables actually conform to the normal distribution, forcing humans into a bell curve has the capacity to stifle growth. In using a traditional approach to teaching that assumes a few students will do above-average work, some average work, and some below average work with some failing, grades do not motivate or inspire most students. The ideal outcome in this scenario is to have most students near the middle of the distribution. In practical terms, on a test with 100 items, the average score is 80, so most students miss 20% of the material which means they are “clueless” when it comes to one-fifth of the material. Is this an optimal outcome? Additionally, if teaching has a goal of producing a normally distributed grading system where most students do not understand 20% of the material, you, as a teacher, may be intentionally unclear in your presentation.

Geher goes on to say that teachers should inspire students to “see how awesome the content is and take them on a journey of discovery that allows each student to fully master the material at hand.” If this approach is used, many scores land in the high range, with few in the lower range as in the “J” curve as the following illustrates:

“J” Curve

This curve represents a scenario where all the students are learning and scoring above average, i.e., above the 50th percentile with many high scores and a few very high scores.

Can this use of curves be remedied? The answer is a resounding “Yes!” The answer is that grading and reporting should always be done in reference to learning criteria, never using the curve (Stiggins, 1994). Using the normal curve as a basis for assigning grades is detrimental to teaching and learning because it pits students against one another in a competition for the few high grades given by the teacher. Students learn that helping each other will threaten their chances for success (Johnson, et al. 1979). Learning is reduced to a game of winners and losers—with most students falling into the “loser” category (Johnson and Johnson, 1989). Research also has shown that what appears to be a direct relationship between ability or intelligence and academic achievement depends largely on instructional conditions, and not a normal curve. If the quality of instruction is high and matched to the students’ learning needs, the magnitude of this relationship diminishes dramatically and approaches zero (Bloom, 1976). In short, the fairness and equity of grading on a curve is a myth (Stiggins, 1994).

Stiggins believes that standardized testing has raised awareness of some of the problems schools face, but it has done little to help us solve these problems. He goes on to say that it is time for a “wake-up call” in education because assessments are now doing as much harm as good for student learning (Stiggins, 2014).

This concept leads to what Stiggins refers to as, “A new vision of excellence in assessment,” and that there are assessment practices that can have a positive impact on student learning. In creating a new vision of assessment, Stiggins suggests that having “balanced assessments” at the local level to meet the needs of all students, so instructional decision-makers, should include interim/ benchmark assessments and annual testing.

It is important to note that all assessments do not have the same purpose. Some assessments are designed to support learning directly, and they are formative. Assessments that “certify” learning are summative. There is a mistaken belief that annual tests are sufficient; this is not so!

Classroom assessments are the most effective because they provide information about where a student is in terms of meeting the learning objectives or targets at any given time. They also provide excellent information that can help teachers guide instruction. If classroom assessments aren’t working, the other testing levels cannot undo the damage!

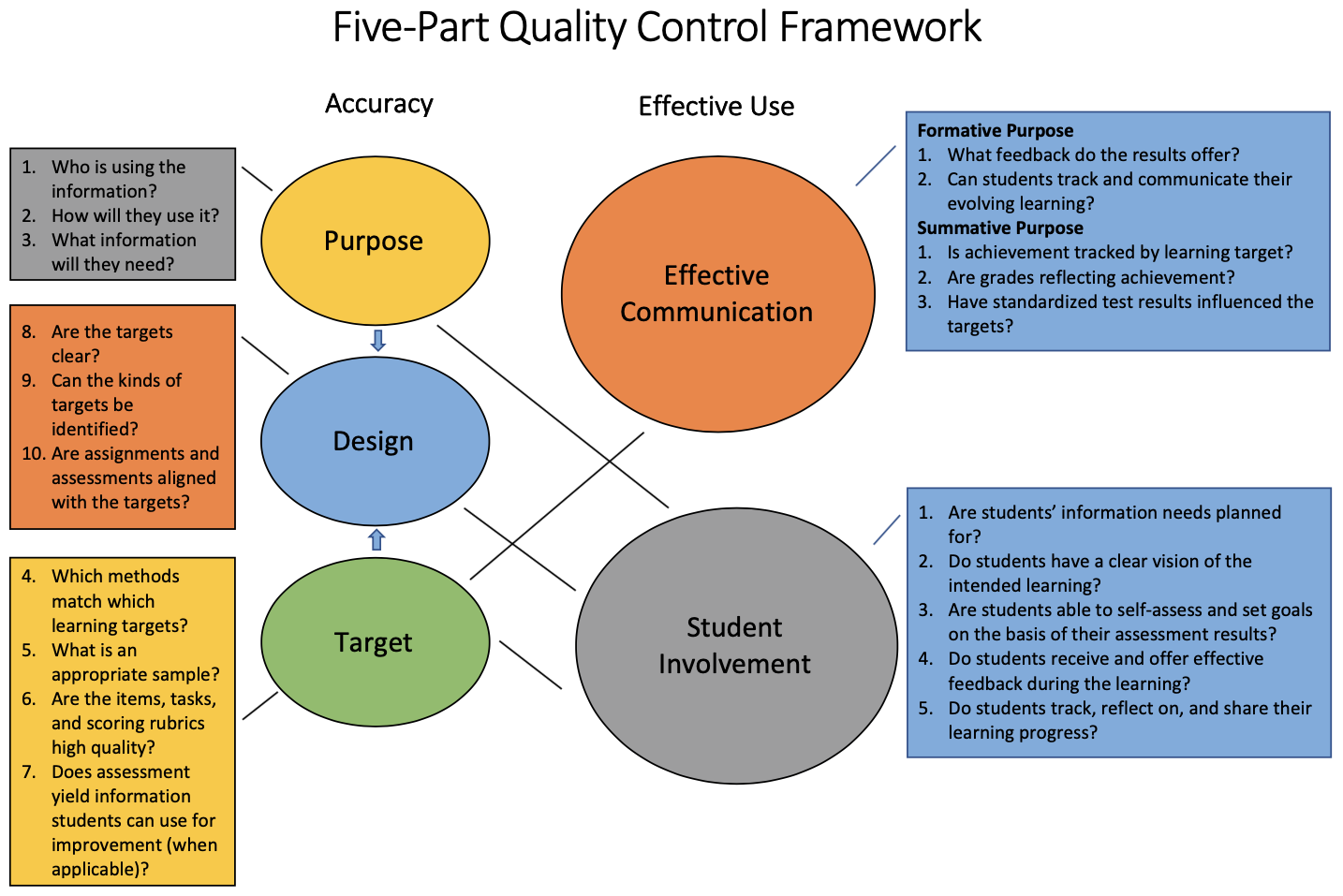

Society’s new directives demand that we look at what assessments are and what they can do to help teachers in their pursuits of helping all students. Educators should be looking at the quality of assessments, and there are a few keys to accomplish this as demonstrated in Stiggins’s Five-Part Quality Control Framework.

Downloadable version: Five Part Quality Control Framework

ILA 14.0

For this ILA, view the following segments of A New Vision of Excellence in Assessment and complete the activity associated with each one.

- A New School Mission Requires a New Assessment Vision (time segment: 0:00-10:28) – Assess your overall approach to classroom assessments for balance by considering the following questions:

- In what ways do you use (or plan to use) the assessment process and results to help students learn more?

- How are you able to gauge how much students have learned at a particular point in time?

- The Critical Matter of Classroom Quality (time segment: 10:28-18:54) – Apply the Five-Part Quality Control Framework to a classroom assessment.

- What components of the framework were easy to identify in the assessment?

- What gaps did you find?

- Assessment for Learning: Productive Emotional Dynamics (time segment: 18:54-26:22) – What are strategies that shape student decisions that result in productive learning?

- Summarize what you discovered using the ILA Response Group in Hypothesis.

Student Self-Assessment

The involvement of students should not be underestimated. One of the best ways to involve students is in the self-assessment process. John Hattie explains why it is important for students to assess their own learning and become, as mentioned in the video, Assessment-Capable Learners.

Test-Enhanced Learning

In addition to student self-assessment, there is a relatively new school of thought called “test-enhanced learning” that focuses on aspects of testing that can support learning.

What is “test-enhanced learning’? In essence, test-enhanced learning is the process of remembering concepts or facts and retrieving them from memory to increase long-term retention of concepts or facts. This “testing effect” is based on studies that focus on different kinds of assessments that include prompts to promote learning when compared to just studying. It is one of the most consistent findings in cognitive psychology (Roediger and Butler 2011; Roediger and Pyc 2012).

The “testing” that actually enhances learning is the low-stakes retrieval practice that accompanies study in these experiments. With that caveat in mind, the testing effect can be a powerful tool to add to instructors’ teaching tool kits—and students’ learning tool kits.

In the guide Test-enhanced learning: Using retrieval practice to help students learn by Brame and Biel (Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching OER; licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.), the authors provide six observations about the effectiveness of testing from the studies that summarize key studies that led to each of these conclusions.

Observation 1 | Repeated Retrieval Enhances Long-Term Retention

The idea that active retrieval of information from memory improves memory is not a new one: William James proposed this idea in 1890, and Edwina Abbott and Arthur Gates provided support for this idea in the early part of the 20th century (James, 1890; Abbott, 1909; Gates, 1917). During the last decade, however, evidence of the benefits of testing has mounted.

In one influential study, Roediger and Karpicke investigated the effects of single versus multiple testing events on long-term retention using educationally relevant conditions (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006). Their goal was to determine if any connection existed between the number of times students were tested and the size of the testing effect.

The results of the study suggest that studying is more effective when the information being learned is only needed for a short time. However, when long-term retention is the goal, testing is more effective. The researchers found testing had a greater impact on long-term retention than did repeated study, and the participants who were repeatedly tested had increased retention over those who were only tested once.

Observation 2 | Various Testing Formats Can Enhance Learning

Smith and Karpicke (2014) examined whether different types of questions were equally effective at inducing the testing effect. The researchers performed a series of experiments with undergraduate students in a laboratory environment, examining the effects of short answer (SA), multiple-choice (MC), and hybrid SA/MC formats for promoting students’ ability to remember information from a text.

Students read four texts, each approximately 500 words long. After each, four groups of students then participated in different types of retrieval practice, while the fifth group was the no-retrieval control. One week later, the students returned to the lab for a short-answer test on each of the reading passages.

Confirming other studies, students who had participated in some type of retrieval practice performed much better on the final assessment, getting approximately twice as many questions correct as those who did not have any retrieval practice. This was true both for questions that were directly taken from information in the texts as well as questions that required inference from the text. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the benefits conferred by the different types of retrieval practice; multiple-choice, short-answer, and hybrid questions following the reading were equally effective at enhancing the students’ learning.

Other experiments replicated these results, although one experiment did find a slight advantage for hybrid retrieval practice (short-answer + multiple-choice) in preparing students for short-answer tests consisting of verbatim questions on short reading passages. These results suggest that the benefits of testing are not tied to a specific type of retrieval practice, but rather retrieval practice in general.

This and other studies suggest that multiple question formats can provide the benefit associated with testing. It appears that the context may determine which question type provides the greatest benefit, with free recall questions, multiple-choice, hybrid free recall/multiple-choice, and cued-recall questions all providing significant benefit over study alone. The most influential studies in the field suggest that free recall provides greater benefit than other question types (see Pyc et al., in press).

Observation 3 | Feedback Enhances the Benefits of Testing

Considerable work has been done to examine the role of feedback on the testing effect. Butler and Roediger designed an experiment in which undergraduates studied 12 historical passages and then took multiple-choice tests (Butler and Roediger, 2008). The students either received no feedback, immediate feedback (i.e., following each question), or delayed feedback (i.e., following completion of the 42-item test). One week later, the students returned for a comprehensive cued-recall test. While simply completing multiple-choice questions after reading the passages did improve performance on the final test, corresponding to other reports on the testing effect, feedback provided an additional benefit. Interestingly, delayed feedback resulted in better final performance than did immediate feedback, although both conditions showed benefit over no feedback.

Observation 4 | Learning is Not Limited to Rote Memory

One concern that instructors may have about using testing as a teaching and learning strategy is that it may promote rote memorization. While most instructors recognize that memory plays a role in allowing students to perform well within their academic domain, they want their students to be able to do more than simply remember and understand facts, but instead to achieve higher cognitive outcomes (Bloom, 1956). Some studies address this concern and report results suggesting that testing provides benefits beyond improving simple recall. For example, the study by Smith and Karpicke (2014) described above determined the effects of testing on students’ recall of specific facts from reading passages as well as their ability to answer questions that required inference. In these studies, the authors defined inference as drawing conclusions that were not directly stated within the passages but that could be drawn by synthesizing from multiple facts within the passage. The investigators observed that testing following reading improved students’ ability to answer both types of questions on a delayed test, thereby providing evidence that the benefits of testing are not limited to answers that require only rote memory.

In a 2011 study, Karpicke and Blunt sought to directly address the question of whether retrieval practice can promote students’ performance on higher-order cognitive activities. They investigated the impact of retrieval practice on students’ learning of undergraduate-level science concepts, comparing the effects of retrieval practice to the elaborative study technique, concept mapping (Karpicke and Blunt, 2011). All students were asked to complete a self-assessment predicting their recall within one week; students in the repeated study group predicted better recall than students in any of the other groups. Students then returned a week later for a short-answer test consisting of questions that could be answered verbatim from the text and questions that required inferences from the text. Students in the retrieval practice condition performed significantly better on both the verbatim questions and the inference questions than students in any other group.

The authors found that retrieval practice produced better performance than did an elaborative study using concept mapping on both types of final tests (short-answer and concept mapping). When they examined the effects on individual learners, they found that 84% (101/120) of students performed better on the final tests when they used retrieval practice as a study strategy rather than concept mapping.

Observation 5 | Testing Can Potentiate Further Study

Wissman, Rawson, and Pyc have reported work that suggests that retrieval practice over one set of material may facilitate learning of later material, which may be related or unrelated. They investigated the use of “interim tests.” Undergraduate students were asked to read three sections of a text. In the “interim test” group, they were tested after reading each of the first two sections, specifically by typing everything they could remember about the text. After completing the interim test, they were advanced to the next section of material. The “no interim test” group read all three sections with no tests in between. Both groups were tested on Section 3 after reading it. Interestingly, the group that had completed interim tests on Sections 1 and 2 recalled about twice as many “idea units” from Section 3 as the students who did not take interim tests. This result was observed both when Sections 1, 2, and 3 were about different topics and when they were about related topics. Thus, testing may have benefits that extend beyond the target material.

Observation 6 | The Benefits of Testing Appear to Extend to the Classroom

All of the reports described above focused on experiments performed in a laboratory setting. Additionally, several studies suggest the benefits of testing may also extend to the classroom.

In 2002, Leeming used an “exam-a-day” approach to teaching an introductory psychology course (Leeming, 2002). He found that students who completed an exam every day rather than exams that covered large blocks of material scored significantly higher on a retention test administered at the end of the semester.

Larsen, Butler, and Roediger asked whether a testing effect was observed for medical residents’ learning about two neurological disorders (Larsen et al., 2009). The residents participated in an interactive teaching session on the two topics and then were randomly divided into two groups. One group studied a review sheet on the concepts first and then took a test while the second group took a test on the concepts first and then studied the review sheet next. Six months later, the residents completed a test on both topics. The authors observed that the testing condition produced final test scores that averaged 13% higher than the study condition.

Lyle and Crawford examined the effects of retrieval practice on student learning in undergraduate statistics class (Lyle and Crawford, 2011). In one section of the course, students were instructed to spend the final 5 to 10 minutes of each class period answering two to four questions that required them to retrieve information about the day’s lecture from memory. The students in this section of the course performed about eight percent higher on exams over the course of the semester than students in sections that did not use the retrieval practice method, a statistically significant difference. This result supports Madeline Hunter’s final step in a lesson, Closure.

Why Is It Effective?

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the effects of testing. The retrieval effort hypothesis suggests that the effort involved in retrieval provides testing benefits (Gardiner, Craik, and Bleasdale, 1973). This hypothesis predicts that tests that require the production of an answer, rather than recognition of an answer, would provide greater benefit, a result that has been observed in some studies (Butler and Roediger, 2007; Pyc and Rawson, 2009) but not in others (Little and Bjork, 2012).

Bjork and Bjork’s new theory of disuse provides an alternative hypothesis to explain the benefits of testing (Bjork and Bjork, 1992). This theory posits that memory has two components: storage strength and retrieval strength. Repeated retrieval events improve storage strength, enhancing overall memory, and the effects are most pronounced at the point of forgetting—that is, retrieval at the point of forgetting has a greater impact on memory than repeated retrieval when retrieval strength is high. This theory aligns with experiments that demonstrate how this study is as (or more) effective as testing when the delay before a final test is very short. The reason is that the very short delay between study and the final test means that retrieval strength is very high—an experience many students can verify from their own cramming experiences. At a greater delay, however, experiences that build retrieval strength (e.g., testing) confer greater benefit than studying.

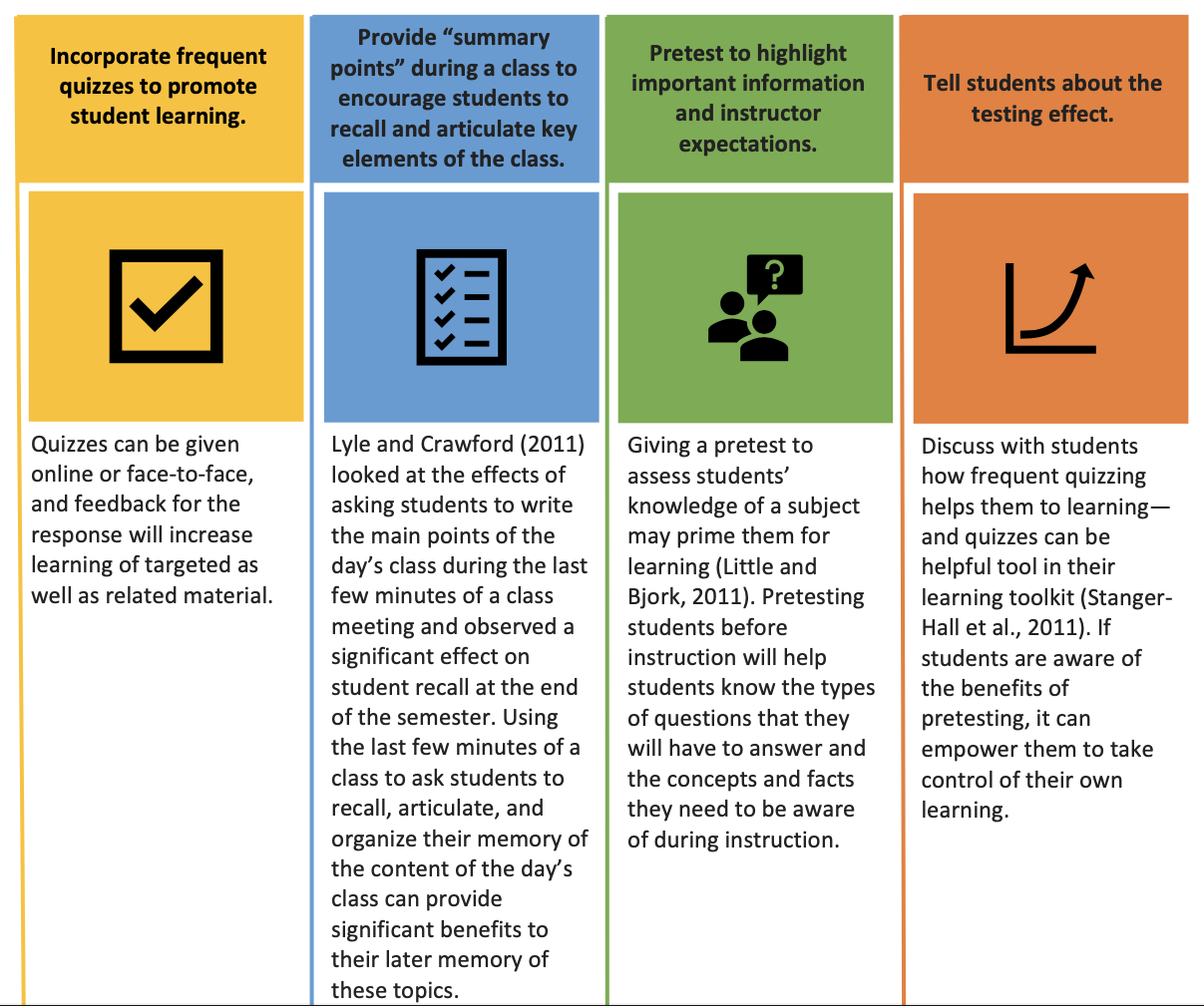

How Can Teachers Implement the Test-Enhanced Learning in Their Classes?

There are many ways to take advantage of the testing effect, some during class time and some outside of class time. The following are a few suggestions.

Test Enhanced Learning Examples

Teachers can use the principles that underlie test-enhanced learning—frequent quizzes and low-stakes opportunities for students to practice recall—to develop approaches that will target the needs of their students.

What Are the Caveats to Keep in Mind?

Keep it low stakes

True formative assessment can help students evaluate their memory of a particular subject.

Share learning goals or objectives

If students know the “targets,” it is easier for them to apply their knowledge, problem-solve, and synthesize their learning. They need to know that the retrieval practice is one strategy to help them learn the basic information they need for these skills—but it’s not the only one.

High Stakes vs. Low/No Stakes Testing

High-stakes testing can have a negative effect on identity-threatened groups. Steele (2010) refers to this as a stereotype threat in which individuals in a stereotyped group do not perform well on high stakes evaluation. Social cues can cause anxiety and produce a cognitive load that interferes with performance of an assessment. This phenomenon has been observed for women in math, African Americans in higher education, white males in sports competitions, and other groups that are negatively stereotyped in a particular area. This effect is magnified in high-achieving people within a specific group—for example, women who are high achievers in math are more likely to have a decline in test scores if they are told that women do not always do well in math (Steele, 2010). For that reason, no or low-stakes formative assessments should be seen as opportunities to learn so that the stereotype threat is avoided.

In addition to looking at strategies for improving assessment scores, there is a growing concern about whether or not we are assessing what actually makes a difference.

Are We Measuring What Matters in Schools?

Angela Duckworth, a psychologist and researcher, began her career as a public-school teacher, and she found that one of her greatest challenges was to help students realize potential. In 2016, she published the book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance in which she summarizes her research of highly successful people in music, professional sports, and the military. She found that two factors, a passion for the subject matter and a willingness to work hard, were better predictors of success than tests of intelligence or natural ability. She discovered that for the highest achievers, “grit,” and not natural talent made the real difference.

The tendency to give preference to people deemed “naturals,” over the “strivers” who work hard but may be better qualified, is a social problem that should be addressed (Tsay, 2015). Duckworth also found that assessments have a narrow focus and that we should be more holistic in our view of what will level the playing field for all students. Her research indicates that we have placed too much emphasis on cognitive ability and that we should broaden our view of students’ capabilities. You may read more about her study in the following article and interview: In Schools, Are We Measuring What Matters?

In addition to placing too much emphasis on cognitive abilities in testing, it is important to consider social and emotional learning which is vital in promoting student success.

Today’s schools are increasingly multicultural and multilingual with students from diverse social and economic backgrounds. Educators and community agencies serve students with different motivation for engaging in learning, behaving positively, and performing academically. Social and emotional learning (SEL) provides a foundation for safe and positive learning and enhances students’ ability to succeed in school, careers, and life (Weissberg, Durlak, Domitrovich, and Gullotta 2016).

Social and Emotional Learning and Testing

Students who have difficulty learning and also taking tests may have emotional or behavioral problems that interfere with their ability to adjust to school and be successful. These students may derive great benefit from Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) that describes the competencies that form the foundation of human interaction (Elias, 2019). This includes how students manage their emotions, make decisions, communicate with others, use compassion and empathy to understand the needs of other people, and build relationships. In addition to academics, students need to learn how to interact with the world.

There are several approaches used to bring SEL into schools (e.g., Durlak, Domitrovich, Weissberg, & Gullotta, 2015; Osher, Kidron, Brackett, Dymnicki, Jones, & Weissberg, 2016), these are typically in four groups: short, effective practices, curriculum-based SEL programs, whole-school SEL approaches, and climate and character approaches (Elias, 2019).

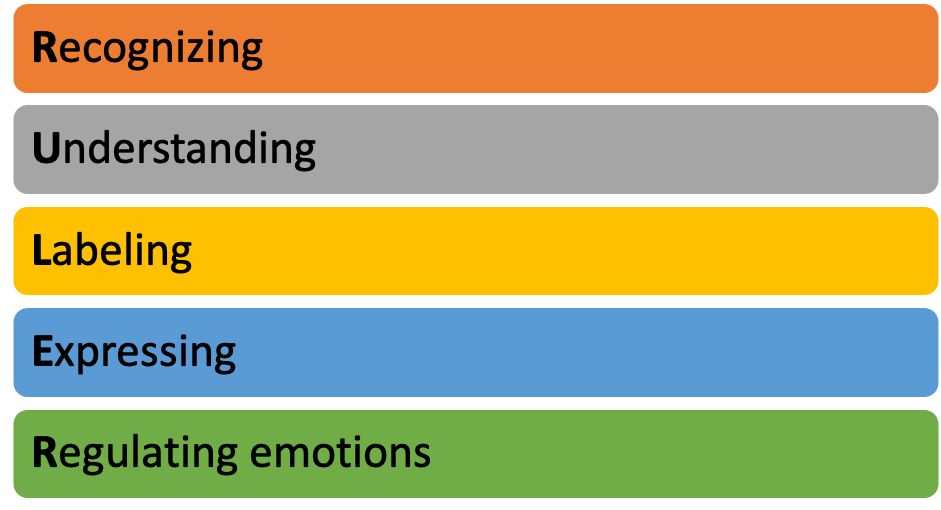

One approach to implementing SEL is RULER which represents the five skills of emotional intelligence, or SEL:

These practices guide how SEL is implemented and also how students and adults should conduct themselves. A school using the RULER approach emphasizes building adults’ emotional intelligence as well as their ability to promote the same competencies in their students by using a common language that includes how leadership, teaching, and learning must be guided by emotion, science, and developmentally sequenced SEL lessons. What can be observed when RULER is in action is the emphasis on building the adults’ capacities to “own” RULER as the key to creating deep impact and long-term sustainability (Brackett, et. al, 2019; Elias, 2019).

Teachers and schools are not able to change all of the contexts in which a student must function, but they can provide a powerful, supportive, affirming SEL-oriented growth experience. The most lasting SEL skill-building results come from high levels of coordinated implementation over multiple years (Elias, 2019).

In addition to the SEL approach, there are ways to evaluate students’ social and emotional learning. Assessing Social and Emotional Learning, an article from Edutopia describes a review of three types of SEL assessments and ways to report student growth. Another resource that can be helpful is one from District Administration on Social Emotional Learning: 3 Actions to Assess Students’ Social-Emotional Learning.

Insight 14.1

When standards were introduced, one of the requirements was that students would be tested to see whether or not the standards were being met. This seemed very reasonable, but complications arose. I was one of the educators selected to work with a corporation that would pilot a test for the state. The committee was tasked with “benchmarking” the test for all the students tested. We set “cut points” of advanced, proficient, partially proficient, and not yet partially proficient. We were encouraged to set cut points that would be challenging to students since we were told that teachers and schools would have ten years to meet the new standards. It was not to be. As soon as the test scores were published, there were many repercussions. The scores of students were ranked compared to other schools, real estate prices jumped or fell, depending on how high or low the test scores were, and some schools were designated as “failing.” My school district hired a statistician to find out why some schools scored high and some scored low. Statistics revealed that there was a 90% correlation between the income level of students’ families and their test scores. When the data was later disaggregated it was discovered that some “failing” schools actually had students who made bigger gains academically than some of the schools in more expensive neighborhoods whose students did not make comparable gains. Schools learned that giving the students formative assessments helped increase learning and also prepared students for the state tests.

Conclusion: Be careful when making judgments about schools based on test scores alone!

Summary

High-stakes testing in the past two decades has taken center-stage in many schools. By having a new perspective on testing as a way to impact all students and not just to “sort and select” students by performance, we can revolutionize how education affects our students’ lives. In addition to considering what strategies and techniques can help students learn and take tests, we must look first at the emotional health and well-being of the students.