13 21st-Century Teachers and Learners – Meeting the Needs of All Learners

‘If a child can’t learn the way we teach, maybe we should teach the way they learn.” –Ignacio Estrada

Essential Questions

- What is the central goal of 21st-century learning?

- How are the skills of the 21st-century teacher different than those in times past?

- Why is it important for teachers to consider universal design when designing curriculum or lessons for all students?

- How can a teacher’s relationship with a student have a positive impact on self-concept and the future?

Introduction

There is now greater diversity than in times past, and a “one-size-fits-all” classroom is no longer appropriate. In the past, the emphasis was on the “3R’s” (reading, writing, arithmetic) as well as social studies, science and language. The model was teacher-centered with an emphasis on teaching strategies that focused on repetition, memorization, and lecturing; and tests were given at the end of the learning cycle to assess student learning. Today, curriculum developers realize the importance of developing educational goals and teaching methods that prepare students for college and future careers (Alismail & McGuire, 2015).

The Educational Landscape in the 21st Century

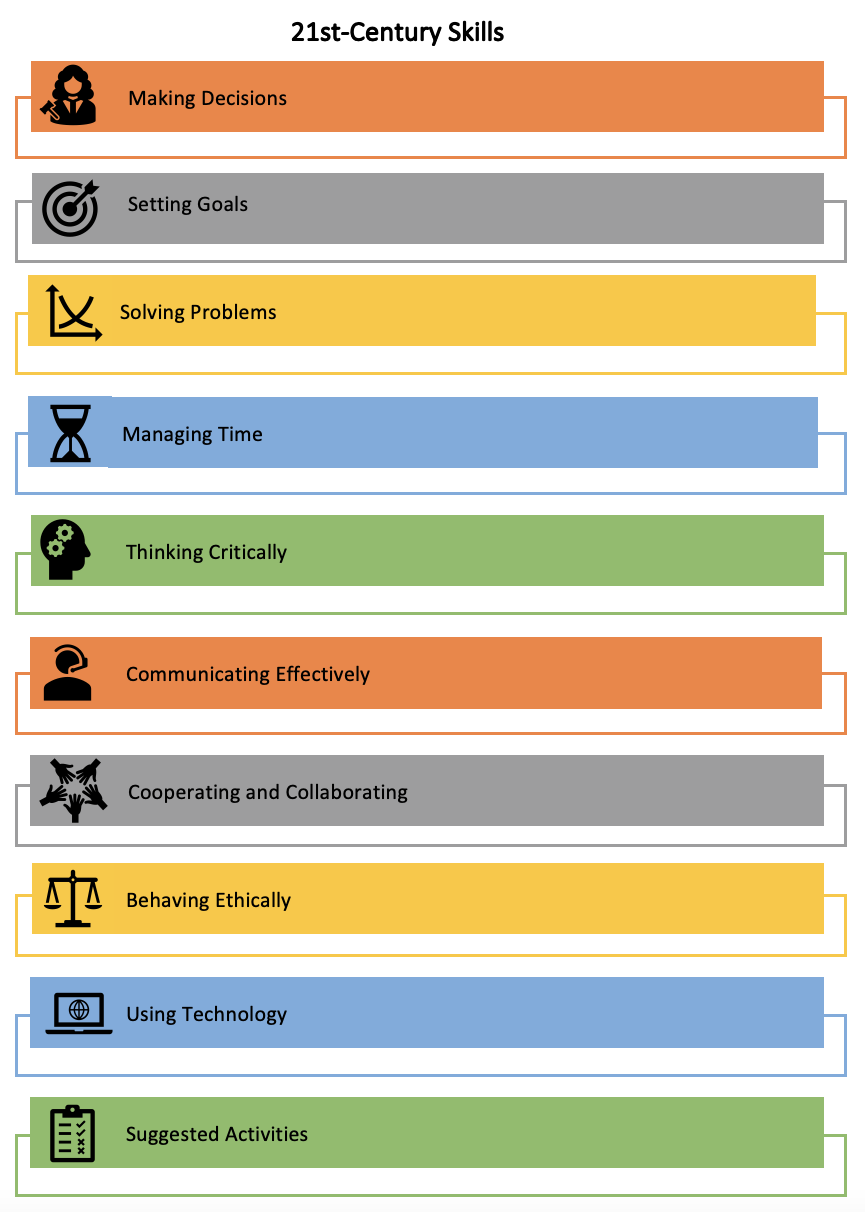

The term 21st-century skills encompasses a broad set of knowledge and skills that are not easy to define because the use of the term is often inconsistent, but they are generally considered to be those outlined in Figure 13.1.

The 21st-century skills were developed because it is often thought that students in this century need a wide variety of skills in addition to the academic standards that have been adopted in many states. The 21st-century skills ideally work in tandem with academic or content standards and can be taught in or out of school. They also lend themselves well to an integrated curriculum, project-based learning, and authentic learning experiences. For more details about the skills, access the link above.

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and Partnership for 21st Century Skills integrated the framework prepared by The Partnership for 21st Century Skills. This plan advocated for the integration of core academic knowledge, critical thinking, and social skills in teaching and learning to support students in mastering the multi-dimensional abilities required in the 21st century. These skills include the “New 3Rs” (Relationships, Routines, and Resilience) of core academic content mastery (Cantor, 2021) and the 4Cs of Critical Thinking, Communication, Collaboration, and Creativity (Stauffer, 2021). By integrating cognitive learning and skills into the curriculum, students can gain a deeper understanding of the subject as well as ways to solve complex problems in the real world.

The Partnership for 21st Century Skills prepared educational standards for the next generation to present an appropriate strategy to apply them. The 21st-century standards:

- focus on 21st-century skills, content knowledge, and expertise

- build understanding across and among core subject areas as well as 21st-century interdisciplinary themes

- emphasize deep understanding rather than shallow knowledge.

- engage students with real-world data, tools, and experts they will encounter in college, on the job, and in life

- allow for multiple measures of mastery (Alismail & McGuire, 2015)

By adopting a 21st-century curriculum, there can be a blend of knowledge, thinking, innovation skills, media, literacy, information, and communication technology coupled with real-life experiences and authentic learning that are integrated into the academic subjects (Lombardi, 2007). The central goal for curriculum in the 21st century is a focus on the construction of knowledge that encourages students to create information that has value for them and helps them gain new skills. Developing curriculum that is based in the real world also encourages student participation and supports them in understanding the knowledge rooted in the core subjects. Additionally, this will provide students with the opportunity to develop civic, financial, environmental, and health literacies as well as global awareness.

Curriculum that emphasizes the construction of knowledge and is rooted in the core subjects is the starting point. The question becomes: how do we reach all the learners with diverse needs?

The 21st-Century Teacher

To meet the needs of learners, teachers should possess additional skills, including those of technology. Palmer (2015) describes 15 Characteristics of a 21st-Century Teacher that include: a learner-centered classroom, students as learners, users, and producers of digital content, and project-based learning. A more complete description of these skills can be found in the article: 15 Characteristics of a 21st-Century Teacher.

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) re-conceptualizes curriculum design by placing student diversity at the forefront and designing flexible and accommodating curriculums to meet the needs of diverse students (Strangeman, et. al, 2020). This is a relatively new approach to curriculum that is grounded in the belief that each learner is unique and brings different strengths and areas of weaknesses to the classroom (Rose and Meyer, 2002). In classrooms today, students come from diverse backgrounds, cultures, socioeconomic, and disability groups. Many traditional curriculums are designed to meet the needs of a “typical” or “average” student. This can be a significant disadvantage for students not in these categories and can lead to barriers that make access and progress more difficult.

UDL is based on the same principles as universal design in architecture which began as a movement to design structures with all users in mind and includes features like ramps and elevators to make access easier (Connell, et al., 1997). Not only does the design allow access for students with disabilities, but an unexpected side effect of this process is that it provided accessibility for all individuals, therefore, usability benefitted more people. The next step was to apply UDL to curriculum by considering the needs of all students, beginning at the planning stage. By maximizing access to information, it provided additional access to learning (Rose & Meyer, 2002).

Application of UDL during the Curriculum Design Process

Neuroscience has also contributed to the guidance of UDL in curriculum design. Research in neuroscience includes three broad neural networks in the brain that oversee three avenues of learning: UDL classifies these three avenues as recognition, strategic, and affective networks (Cytowic, 1996; Luria, 1973; Rose & Meyer, 2002). UDL stresses that these three abilities differ from student to student. As a way to meet this challenge there are three UDL principles that guide a flexible curriculum design process:

- to support recognition learning, provide multiple, flexible methods of presentation,

- to support strategic learning, provide multiple, flexible methods of expression and apprenticeship, and

- to support effective learning, provide multiple, flexible options for engagement (Rose & Meyer, 2002).

The three principles can be included in the design of goals, the inclusion of strategies and resources, flexible presentations and assessments. Using an assessment as an example, curriculum designers can include a range of media, formats, and response options so that the student’s knowledge and skills are assessed and not their ability to cope with the format and presentation. This is true for both formative and summative assessments.

Multimedia tools and peer reviews provide feedback to students that can improve their work and increase team collaboration. Technology also has the advantage of allowing students to gain information and knowledge as well as the development of different literacies even if they are working by themselves. This can encourage students to pursue individual passions for learning about specific topics that support creative thinking and innovation skills.

21st-Century Students as Consumers of Information

According to Carol Ann Tomlinson, 21st-century schools must prepare students to be wise consumers of information, and confident producers of knowledge. The 21st-century student populations are more heterogeneous than in the past, which means schools need to become more responsive to diverse cultures, languages, experiences, economics, and interests—and do this in ways that provide equity of access to dynamic learning experiences to meet the needs of all learners.

Current research suggests that the best vision of a 21st-century classroom is centered on the learners, knowledge, assessment, instruction, and the classroom community (National Research Council, 2000). Technology, when used effectively, can support teachers and students in a variety of ways, including curriculum planning, differentiated learning opportunities, assessment development and meeting the needs of a diverse student population.

There is agreement among educators and the public that we must establish certain “core skills” that should be included in this framework (Binkley, et al, 2012). The challenge is that there is no single framework for what is included in the list of skills. The Partnership for 21st Century Skills framework (Dede, 2010) has two categories of skill groups. The first is “perennial” skills, or those retained from the 20th century, but are still valuable in the 21st century. These skills include communication, creativity, and critical thinking. The second category is “contextual skills,” or those unique to the 21st century that includes the ability to manage large quantities of digital information and data that are important for decision-making.

The Metiri Group and the North Central Regional Education Laboratory (NCREL) developed the 21st Century Skills Framework (Burkhardt, et al. 2003), with the following four, key categories of skills (refer to the P21 Framework Definitions for a full description of these skills):

- digital age literacies,

- inventive thinking,

- effective communication, and

- high productivity.

It seems that the needs of the 21st-century classroom are different than they were in the past. One key difference is that teachers are facilitators of learning, and it is their responsibility to have a curriculum that supports students in developing skills for an academic program and eventually the workplace. Another key difference is the emphasis on a project-based curriculum that encourages higher-order thinking skills, effective communication, and technology skills. One common thread has become the need for successful collaboration as a part of student learning. To accomplish these things, it is important to move beyond the skills of the 20th century and master those of the 21st century. The 21st Century Skill: Rethinking How Students Learn discusses some strategies for doing just that.

“Teaching Up” and the 21st-Century Teacher

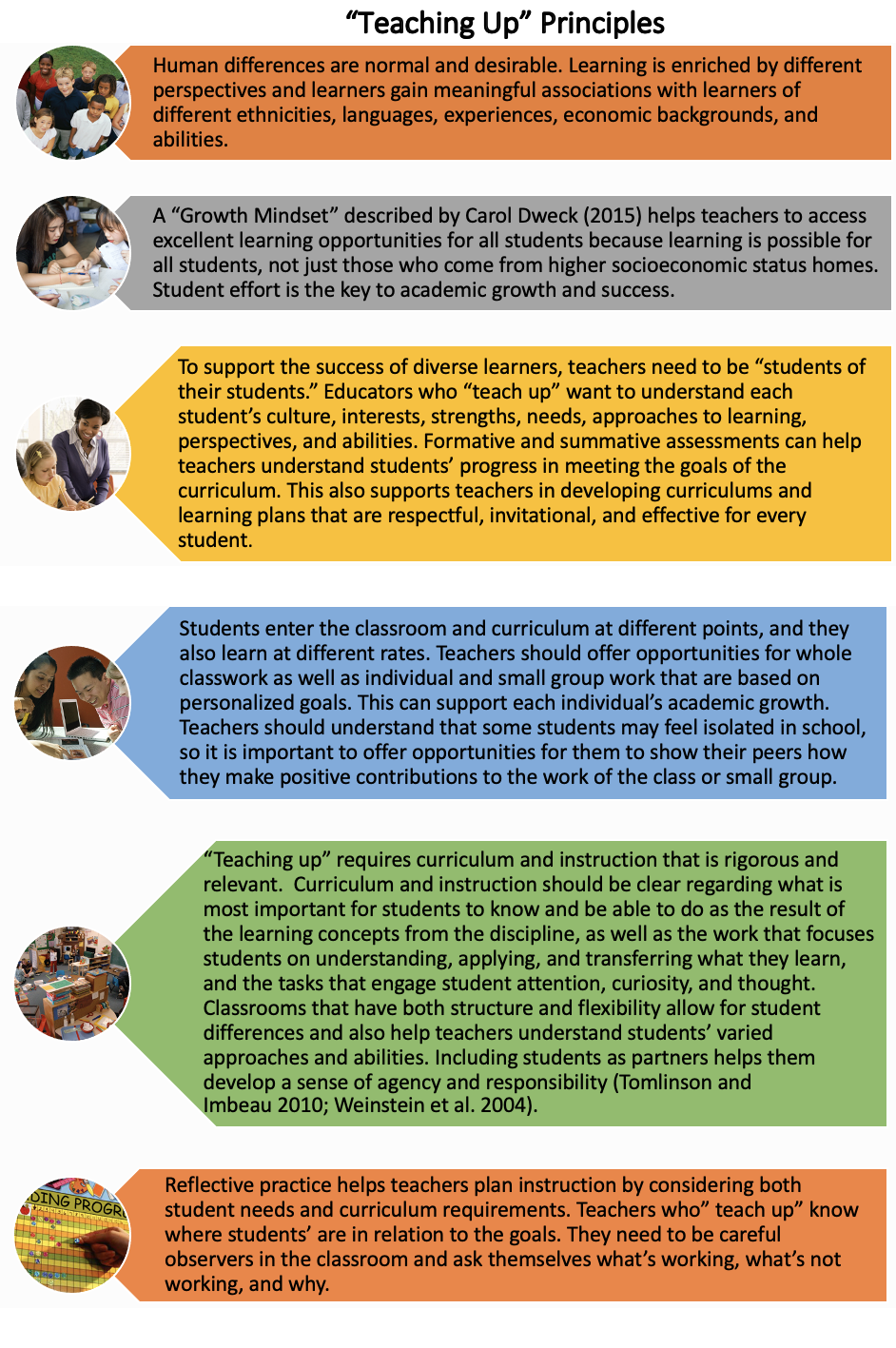

Another plan that is designed to maximize learning for all students in mixed-ability classrooms is “Teaching Up” which has been developed by Tomlinson and Javious (2012). In developing differentiated or responsive instruction, teachers begin by planning with a specific group of students in mind. They may also choose to plan from the academic standards using grade-level expectations and differentiate “up” or “down” from that point.

Other teachers may want to begin by developing learning experiences that focus on the essentials for students who have more difficulty with particular content to help clarify the essentials and to differentiate from that beginning position. “Teaching up” requires that the teachers begin by developing tasks that are a challenge for high performing learners, and then to differentiate or scaffold learning in ways that support a broad range of students in working with “advanced” levels of knowledge, understandings, and skills. “Teaching up” is rooted in six key principles as shown in Figure 13.2 (Tomlinson, 2015).

Developing Inclusive Practices in Literacy

Anita Nigam, author of the proceeding article, was born in India and taught elementary students there and in the U.S. She is currently a faculty member at a University in Illinois where she specializes in literacy and English language learning (ELL).

Classrooms now more than ever need to reflect the diverse cultures present as they provide a range of perspectives and experiences that can help shape the minds of all the students in mainstream classes. Previously, if there were students needing special attention, they were provided assistance outside the classroom; however, the focus now is to have the teacher meet the needs of all learners within the classroom, leading to the birth of inclusive classrooms. Therefore, the onus of developing culturally responsive classrooms falls on the shoulders of all classroom teachers. However, many teachers grew up without much exposure to cultural diversity and do not see the potential of all students nor the many issues and challenges that some students face (Sleeter, 2008). Teachers of color tend to recognize the literate potential of students of color and have high expectations for them but are not always aware of how to use students’ cultural knowledge to inform their teaching practices (Villegas & Davis, 2008).

The summary of this qualitative research study is aimed at promoting awareness and implementation of developing culturally responsive literacy practices among preservice teachers who were part of the Elementary Education Program in a private university in the Midwest region of the United States. All 16 preservice teachers had a broad definition of diversity, i.e., the inclusion of students from special population which included ELLs and learners from diverse populations.

Throughout the semester the preservice teachers worked in an elementary school which was their clinical placement and also at an after-school program that offered tutoring services for students from grades one through five of the elementary school. Preliminary results and findings from the study show four major themes that emerged from the analysis of the data:

- creating differentiated assignments for students to do after they finish their work to meet the needs the different abilities that students have,

- pairing mainstream students with students from diverse backgrounds to talk about a family or a public event and encourage nurturing relationships and a welcoming environment,

- using the trading card strategy for vocabulary where students are given the choice to write the definition in their native language,

- reading “First You, Then Together” where the teacher would have students read a page or two to themselves before reading it together while having the students follow along with their fingers or reading aloud with the teacher while going over the same page, and

- using technology such as Chromebook to enable dictation so students are able to demonstrate their knowledge and writing abilities without having to jump through extra hurdles to complete the writing tasks required of them within the lesson.

These findings, though modest, are an attempt to create awareness of social equity literacy practices among preservice teachers teaching at a local elementary school with a diverse population.

A Place at the Table: Create a Community of Learners

In the following article, A Place at the Table: Create a Community of Learners, Yvonne Siu-Runyan, a former classroom teacher, university professor, and past president of the National Council of Teachers of English, has summed up what is needed to help all learners gain literacy skills.

In order to learn, all students need to take risks. In order to take risks, all students need a safe place to learn and to be seen. That is, your students need to know that in your classroom, they each have a seat at the table and have voices and stories to share.

- Read aloud every day and be purposeful in what you choose to read.

- Books and stories provide common experiences for students.

- Books and stories nurture an understanding of self and others.

- Books and stories shape our understanding of the world around us and ourselves.

- Listen to your students’ conversations in various settings. This simple action will provide you with useful information to guide your instruction and conversations with your students.

- Develop Partnerships with Parents/Guardians.

- Your best and most important ally are the parents/guardians.

- Never doubt the power of having a good relationship with parents/guardians.

- Thus, your first contact with parents/guardians should be a positive, not a negative one.

- Do call the parents/guardians of your students and make sure you have positive things to say? Most parents/guardians expect the worst.

- Before you end your conversation, be sure to tell the parent/guardian to share the positive information with the child.

- The next day watch — this child will stand taller, do more, and take more learning risks because this child will know that you care, and learning involves caring and LOVE.

- Read and write alongside your students and be part of the learning community in your classroom.

- Students like it when their teachers read and write with them and share their reading and writing.

- By sharing your literacy experiences with students, they get an inside-out look at the power of reading and writing and you become a member of the literacy club in your classroom.

- Show the students your “inside out” process and make it visible.

- Students learn when their teachers model and show their inside out process.

- You might want to take a risk and ask your students the following questions:

- What do I do that helps you as a reader, writer, and thinker?

- What do I do that does not help you as a reader, writer, and thinker?

- When I asked these two questions of my students, I learned that my students liked it when I read and wrote alongside them for it made visible the processes involved in reading, writing, and thinking.

- Have a classroom library and showcase books. If we want our students to read, then it makes good sense that books must be accessible.

Books fall open; we fall in! I love this saying, “Ah … the power of the printed page.” Do create a classroom learning environment where students are surrounded by books. For if there are a wide variety of books in your classroom, your students will find books that speak to them. There is a plethora of stunning books written for young people like never before. Be sure to have books in which our young can see themselves and to which our students can relate. In this way, our young will be better equipped to reach back in order to reach out, and then reach out in order to reach forward with courage and love in our quest to make this place we call Earth a better place for all for: Education should liberate, not indoctrinate.

I end with this old Chinese Proverb: “Yin Zhen Zhi Ke,” or “Drinking poison to quench thirst.” This Chinese saying warns us that measures taken in the short term to solve a problem may be more damaging than the problem.

Be wary of narrow standards and standardized tests. Learning is much more.

Homeschooling

For those parents and students who want to differentiate based on individual needs, homeschooling is becoming one of the “go-to” alternatives.

Home-based education led by families has been practiced by cultures around the world and down through history, and it has played an influential role in Western civilization (Gordon & Gordon). Homeschooling today is the parent-led practice of teaching their children rather than attending a public school (Ray, 2000).

During American Colonial times, children were taught at home using the Bible for reading. Writing, math, and vocational skills were usually taught by the father (Ray, 2017). The children of missionary families or families who traveled were taught using mail-order curricula that they could take to different parts of the world. Homeschooling at that time was often a joint effort between parents, tutors, older children, and families. At times, parents or groups would sometimes pool their resources to employ a teacher for more support (Hill, 2000). At the end of the 19th century, homeschooling was widely practiced, and public or formal school attendance was voluntary (Tyack, 1974).

More than two million children today are homeschooled (Ray, 2017). The number of children in homeschools is now larger than the New York City public school system and even larger than the Los Angeles and Chicago public school systems combined (Hill, 2000; Ray, 2017). As a result, there is a rising need for support, collaboration, and professional expertise. Groups for home educators and networks are growing and becoming a new type of educational institution (Hill, 2000). They are usually identified as associations, co-ops, or charter schools (Collom, 2005; Hill, 2000). Home school parents and supporters of this alternative form of education have developed new teaching models and curriculums to help parents become educators (Tilhou, 2020).

Common beliefs, motivations, and the choice to homeschool attract homeschool parents/educators who want mutual support and collaboration. These families do not want to be isolated, so they make use of services and resources from experts, and they form teams that gain others’ support, often through organized groups (Collom, 2005; Hill, 2000). The advantages of this collaborative effort can extend beyond families that collaborate with the support of public funds for materials and resources, facilities, and administrator’s time (Hill, 2000).

Collom (2005) found that the newest homeschoolers are highly motivated by academic reasons. The decision to home school can be categorized into four areas and include those who:

- are critical of public schools,

- attracted to home-based public charter,

- have ideological reasons, and

- focused on family and children’s needs.

Results also indicate that the home-based charter has been the most popular motivation, and criticism of public schools had a slightly lower score.

Homeschool Partnerships with Public Education and the Future

Thomas (2016) has stated that if home parents/educators see value in the resources in their community, public school parents may likely feel the same way. Additionally, if homeschooling parents make educational decisions based on the goal of providing high-quality learning experiences, teaching faith, setting student goals, and meeting family needs, public school parents may also have similar goals. Can public schools provide a variety of choices parents are wanting? Is it possible for public schools to provide more customized schedules that fit the changing interests and needs of public-school families? Thomas (2016) argues, after examining homeschool families’ instructional decisions and motivations, that public education ought to find more ways to listen to parents’ needs and understand the educational goals they have for their children.

By considering alternative educational models and parental motivations for forming and joining the homeschool movement, public education may gain valuable insights about meeting the needs of families in the 21st century (Tihou, 2020). There are currently school districts that engage in partnerships with homeschool educators. Partnerships allow homeschool students to access classes and programs while maintaining the respect that the child’s primary teacher is his or her parent (Dahlquist, et al. (2006). It may be advantageous for public schools to adopt inclusive policies that offer a range of partnership options with homeschool families as a way to improve communication and create more responsive public spaces where responsibilities for raising the next generation are shared (Thomas, 2016).

The prevalence of homeschool support groups and associations is growing across the United States. Members of these groups come from a variety of backgrounds, but all have a shared interest in providing quality education for their children. What has emerged from this like-mindedness is a movement of millions across the United States not only to educate one’s own child but to come together and form groups which lead to a greater impact on children’s learning and parents’ teaching. What is still unknown is the impact this movement may ultimately have.

Insight 13.0

Gone are the days when a teacher could lecture to a class for 30 minutes to an hour and keep their attention.

To be effective, teachers today must be knowledgeable about different content areas, as well as models and strategies for engaging all students in meaningful learning experiences. Parents make choices about their children’s education, and public schools are, in effect, competing with charter schools and homeschools for students.

ILA 13.0

Several excellent resources for meeting the challenges of 21st-century learning are available. For this ILA, view two or more of the preceding videos and post your biggest “takeaways” using in the ILA Response Group in Hypothesis.

Connecting to the 21st-Century Student

Cultural Diversity: Dr. Geneva Gay

Dr. Geneva Gay from the University of Washington, Seattle answers the question “Why is it important for faculty to employ culturally responsive teaching practices?”

The Power of a Teacher | Adam Saenz | TedEx Yale

Summary

Teachers and students in the 21st century must have broader and more varied skills than their counterparts of the past. Incorporating Universal Design as a part of curriculum planning can ease access to learning for many students. Some parents have chosen homeschooling as a way to meet the educational needs of their children. Carol Tomlinson and others find that differentiating instruction through “teaching up” can meet the needs of a diverse classroom.