2 Historical Events and Philosophical Influences in Curriculum and Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

“He who controls the curriculum controls history.” —Arthur Schlessinger, The Disuniting of America

Introduction

To fully understand why we have the curricula we do today, it is necessary to take a look back at the historical foundations of curriculum in the U.S. as well as the roots of curriculum in ancient civilizations that have an influence today. Schlessinger (1991) asks a critical question: What should we be teaching school children? This is an avenue for other questions:

- With all the things that divide us, and what is it that can hold Americans together?

- What is the historian’s role in all this?

He goes on to state, “The historian’s goals are accuracy, analysis, and objectivity in the reconstruction of the past. . . History as a weapon is an abuse of history.”

As teachers and developers of history, it is very important to know what has been taught, what is being taught, and how can we develop curriculum that teaches students with wisdom and accuracy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy, which was developed in the 1950’s and later revised, articulates many kids of learning, recognition and recall to analysis, synthesis and the production of ideas and performance (Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005).

Essential Questions

- How has history influenced curriculum?

- Why has Bloom’s Taxonomy been used extensively by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching

- How is Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy different than the original Taxonomy?

- Why is it important to know what has been taught, what is being taught, and how we can develop curriculum that teaches students with wisdom and accuracy?

Curriculum in Formal Education

In formal education or schooling, a curriculum is the set of courses, course work, and content offered at a school or university. A curriculum may be partly or entirely guided by an external, governing body, often the state departments of Education in the U.S (Curriculum Studies), p. 130).

Curriculum questions have been raised since Plato’s design for education in his ideal State, (Flinders & Thornton, 2013). In the U.S. in the 18th century, how curriculum was developed and implemented varied greatly from what we see today.

Traditional Education

In all societies, traditional education was aimed at learning the ways of the parents. It was, and still is in some communities, a very conservative form of education and emphasizes on maintaining the status quo in society. The culture, traditions, and practices of the people are passed on from one generation to the next as evidence in methods that do not change much over the years.

Ancient Era

From Curriculum Studies, p. 50

Curriculum can be traced to the ancient era of the Greek, Roman, Hebrew and Christian periods. Greek education, which has influenced the current world systems of education, is credited to the work of Socrates and other Greek scholars such as Aristotle. The main aim of Greek education was good citizenship for the populace, who would support and defend the state and its laws; development of a rational mind; and creativity that influenced the arts

Roman education emphasized equipping the citizenry with knowledge and skills to defend the state; respecting tradition as the foundation of the culture; and highlighting the value of practical skills to maintain daily life among other educational aims. On the other hand, Christian education focused primarily on moral education and character building

Historical Foundations of Curriculum in the U.S.

From Curriculum Studies, p. 130

In The Curriculum, the first textbook published on the subject in 1918, John Franklin Bobbitt said that curriculum, as an idea, has its roots in the Latin word for “race-course” explaining the curriculum as the course of deeds and experiences through which children become the adults they should be for success in adult society. Furthermore, curriculum encompasses the entire scope of formative deeds and experiences occurring in and out of school, and not just experiences occurring in school; experiences that are unplanned and undirected, and experiences intentionally directed for the purposeful formation of adult members of society.

The following slide show provides more information about the history of curriculum in the U.S.

- Curriculum and Education Part 1_Etext_Captioned

- Curriculum and Education Part 2_Etext_Captioned

- Curriculum and Education Part 3_Etext_Captioned

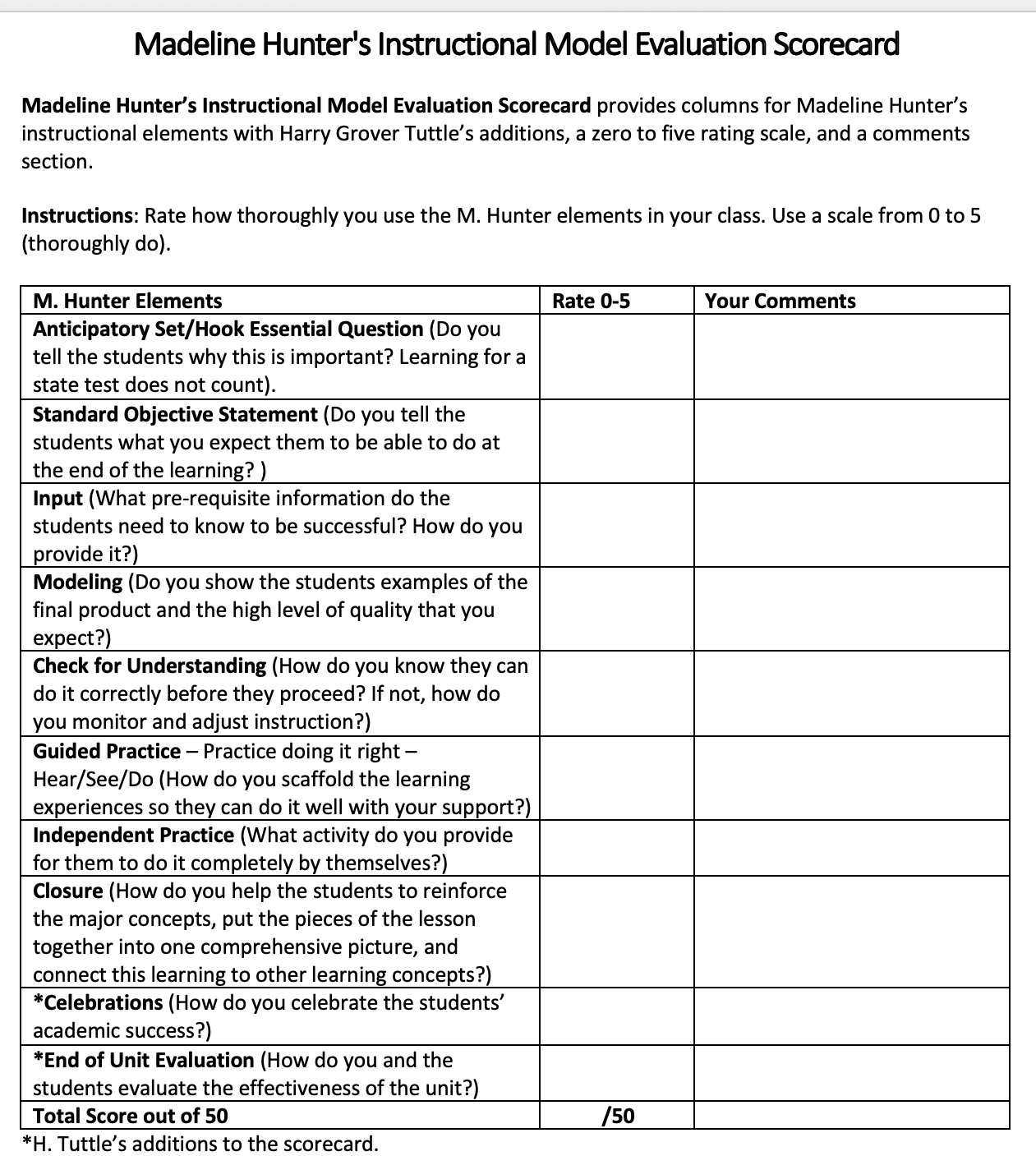

The following is an image of Madeline Hunter’s Instructional Model Evaluation Scorecard as mentioned in Curriculum and Education video presentation.

Madeline Hunter’s Instructional Model Evaluation Scorecard

Downloadable adapted version: Madeline Hunter Instructional Model Evaluation Scorecard

ILA 2.1

Reflect on how history speaks to professional practice in teaching. How might the trends in society today influence curriculum in the future? Utilize the annotation tool for capturing your thoughts.

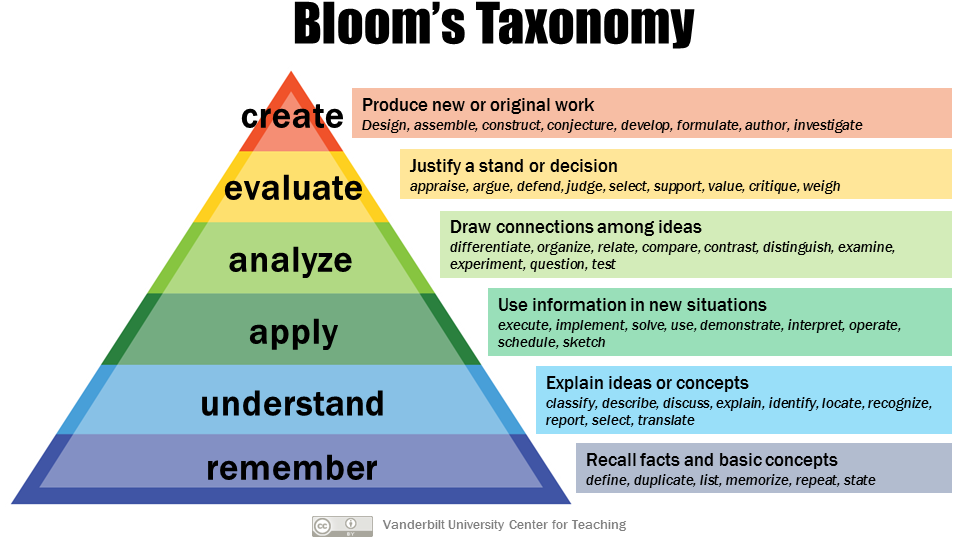

Bloom’s Taxonomy

From P. Armstrong, Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching, and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Many curriculum developers have incorporated Bloom’s Taxonomy into curriculum because they have found it helpful to teachers and administrators when defining standards and creating lessons.

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom with collaborators Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl published a framework for categorizing educational goals: Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Familiarly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy, this framework has been applied by generations of K-12 teachers and college instructors in their teaching.

Following are the authors’ brief explanations of these main categories from the Appendix of Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Handbook One, pp. 201-207).

Table 2.1: Cognitive Levels with Descriptions

| Cognitive Level | Description |

| Knowledge | “involves the recall of specifics and universals, the recall of methods and processes, or the recall of a pattern, structure, or setting.” |

| Comprehension | “refers to a type of understanding or apprehension such that the individual knows what is being communicated and can make use of the material or idea being communicated without necessarily relating it to other material or seeing its fullest implications.” |

| Application | “refers to the ‘use of abstractions in particular and concrete situations.’” |

| Analysis | “represents the ‘breakdown of a communication into its constituent elements or parts such that the relative hierarchy of ideas is made clear and/or the relations between ideas expressed are made explicit.’” |

| Synthesis | “involves the ‘putting together of elements and parts so as to form a whole.’” |

| Evaluation | “engenders judgments about the value of material and methods for given purposes.” |

Barbara Gross Davis, in the “Asking Questions” chapter of Tools for Teaching, also provides examples of questions corresponding to the six categories. This chapter is not available in the online version of the book, but Tools for Teaching is available in the CFT Library. See its ACORN record for call number and availability.

The framework elaborated by Bloom and his collaborators consisted of six major categories:

- Knowledge

- Comprehension

- Application

- Analysis

- Synthesis

- Evaluation

The categories after Knowledge were presented as “skills and abilities,” with the understanding that knowledge was the necessary precondition for putting these skills and abilities into practice.

While each category contained subcategories, all lying along a continuum from simple-to-complex and concrete-to-abstract, the taxonomy is popularly remembered according to the six main categories.

Bloom’s Taxonomy underpins the classical ‘knowledge, attitude, skills’ structure of learning methods and evaluation. It remains the most widely used system of its kind in education particularly, and also in industry and corporate training. It’s easy to see why, because it is such a simple, clear, and effective model, both for explanation and application of learning objectives, teaching and training methods, and measurement of learning outcomes.

The Revised Taxonomy (2001)

A group of cognitive psychologists, curriculum theorists and instructional researchers and testing and assessment specialists published in 2001 a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy with the title A Taxonomy for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment. This title draws attention away from the somewhat static notion of “educational objectives” (in Bloom’s original title) and points to a more dynamic conception of classification.

The authors of the revised taxonomy underscore this dynamism, using verbs and gerunds to label their categories and subcategories (rather than the nouns of the original taxonomy). These “action words” describe the cognitive processes by which thinkers encounter and work with knowledge.

Table 2.2 Cognitive Levels with Action Word Examples

| Cognitive Level | Action Word Examples |

| Remember |

|

| Understand |

|

| Apply |

|

| Analyze |

|

| Evaluate |

|

| Create |

|

In the revised taxonomy, knowledge is at the basis of these six cognitive processes, but its authors created a separate taxonomy of the types of knowledge used in cognition:

- Factual Knowledge

- knowledge of terminology

- knowledge of specific details and elements

- Conceptual Knowledge

- knowledge of classifications and categories

- knowledge of principles and generalizations

- knowledge of theories, models, and structures

- Procedural Knowledge

- knowledge of subject-specific skills and algorithms

- knowledge of subject-specific techniques and methods

- knowledge of criteria for determining when to use appropriate procedures

- Metacognitive Knowledge

- strategic Knowledge

- knowledge about cognitive tasks, including appropriate contextual and conditional knowledge

- self-knowledge

Mary Forehand from the University of Georgia provides a guide to the revised version giving a brief summary of the revised taxonomy and a helpful table of the six cognitive processes and four types of knowledge.

Why Use Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy in Curriculum Development and Lesson Planning?

The authors of the revised taxonomy suggest a multi-layered answer to this question, to which the author of this teaching guide has added some clarifying points:

- Objectives (learning goals) are important to establish in a pedagogical interchange so that teachers and students alike understand the purpose of that interchange.

- Organizing objectives helps to clarify objectives for themselves and for students.

- Having an organized set of objectives helps teachers to:

- “plan and deliver appropriate instruction;”

- “design valid assessment tasks and strategies;” and

- “ensure that instruction and assessment are aligned with the objectives.”

ILA 2.2

As an educator how are Bloom’s levels and examples helpful to teachers in developing lesson plans and meeting standards? Utilize the ILA Responses Group in the Hypothesis annotation tool to share your thoughts.

Summary

It is important to understand the influence of history on curriculum because there are many competing visions of teaching and learning that affect curriculum today. Bloom’s Taxonomy provides the foundation for the classical structure of teaching and learning, and the Revised Taxonomy is widely used because it is an effective model for writing curriculum and measuring outcomes.

In moving from the historical influences of curriculum and the influence of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, the importance of philosophy, and different curriculum philosophies that guide the development and implementation of curriculum follows in the next chapter.