18 – Proposals

Designing and Formatting Proposals

Suzan Last; Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt; Kalani Pattison; Matt McKinney; and James Francis, Jr.

When you write a proposal, you must persuade the reader that your idea is the one most worth pursuing. Proposals are persuasive documents intended to initiate a project and convince the reader to authorize a course of action proposed in the document. These projects might include proposals to

- Perform a task (such as a feasibility study, a research project, etc.)

- Provide a product

- Provide a service

Types of Proposals

Proposals fall into two distinct categories: solicited vs. unsolicited; and internal vs. external. The first category refers to how the audience advertises (or does not advertise) the situation they want a response to.

Solicited proposals. An organization identifies a situation or problem that it wants to improve or solve and issues an RFP (Request for Proposals) asking for proposals on how to address it. The requesting organization will vet proposals and choose the most convincing one, often using a detailed scoring rubric or weighted objectives chart to determine which proposal best responds to the request.

Unsolicited proposals. A writer perceives a problem or an opportunity and takes the initiative to propose a way to solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity (without being requested to do so). This is often the most difficult kind of proposal to get approved.

The second category, internal vs. external, refers to whether the proposal’s author is part of the organization or not. Both internal and external proposals may be solicited or unsolicited, depending on circumstance.

Internal proposals. These proposals are written by and for someone within the same organization. Since both the writer and reader share the same workplace context, these proposals are generally shorter than external proposals and usually address some way to improve a work related situation (productivity, efficiency, profit, etc.). As internal documents, they are often sent as memos or introduced with a memo if the proposal is lengthy.

External proposals. These proposals are sent outside of the writer’s organization to a separate entity (usually to solicit business). Since these are external documents, they are usually sent as a formal report introduced by a cover letter (or letter of transmittal). External proposals are usually sent in response to a Request for Proposals, but not always.

Sample Proposal Organization

Each proposal is unique in that it must address a distinct audience in a particular context and for a specific purpose. Many companies will have a template that employees should use for internal proposals, and solicited proposals often provide an outline or set of guidelines for proposal contents and organization. A fairly standard organization for many types of proposals is detailed below in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1. Proposal organizational structure.

| Proposal Organizational Structure | |

|---|---|

| Summary | Covers all essential information in the proposal, either to encourage your audience to continue to read the full proposal, or for the convenience of a specific audience who does not have the time or need to read the whole document.

Since the writer has not yet begun the project, they would most likely use a pure summary here. This type of summary ascribes equal weight to all sections of the proposal. In a proposal, this includes methods of data collection, which enables the writer to present their project design persuasively. See Chapter 15: Correspondence and Chapter 20: Recommendation Reports for more discussion on summary types. |

| Introduction/Background | Clearly and fully defines the problem or opportunity addressed by the proposal, and briefly describes how the project will address that need. Convinces the reader (consider persuasive writing strategies) that there is a clear need for and a clear benefit to the proposed idea. |

| Project Description | Describes the project in detail and explains how the project will improve the situation: 1. Confirms feasibility (is it doable?) with consideration to time. What makes the project realistically achievable? 2. Explains the specific benefits of implementing the project and the consequences of not doing it. 3. Gives a detailed description or explanation of your proposed project plan or methodology and the resources needed to achieve goals. 4. Addresses potential obstacles or objections; concedes where appropriate. |

| Credentials | Establishes writer’s qualifications, experience, and authority to lead this project. What is your connection to the problem or opportunity? |

| Timeline | Provides a detailed timeline for completion of the project. Uses a Gantt chart—See “Timelines and Gantt Charts” below—to indicate when each stage of the project will be complete. |

| Budget | Provides an itemized budget for completing the proposed project. |

| Conclusion | Concludes with a final pitch that summarizes and emphasizes the benefits of implementing your proposed idea—but without sounding like an advertisement. |

| References | Lists your research sources to document and credit appropriately; this clarifies and authenticates the project work and avoids fallout of plagiarism. |

Depending on the type of your proposal and your audience expectations, some of these sections may either be in a different order or not present at all. The Credentials, Timeline, and Budget sections, for example, can be found in a different order than listed above. Certain sections may also use different headings or subheadings to more precisely convey the content in their sections. These differences are most common in the Project Description portion of the proposal.

Timelines and Gantt Charts

There are several different types of timelines or schedules that can be used to convey a planned schedule for a project or research. The simplest are lists of dates and deadlines. More complex projects, in which tasks vary in duration, can be worked on simultaneously, or depending on the completion of other tasks, may more clearly convey their schedules or timelines through the use of a Gantt chart.

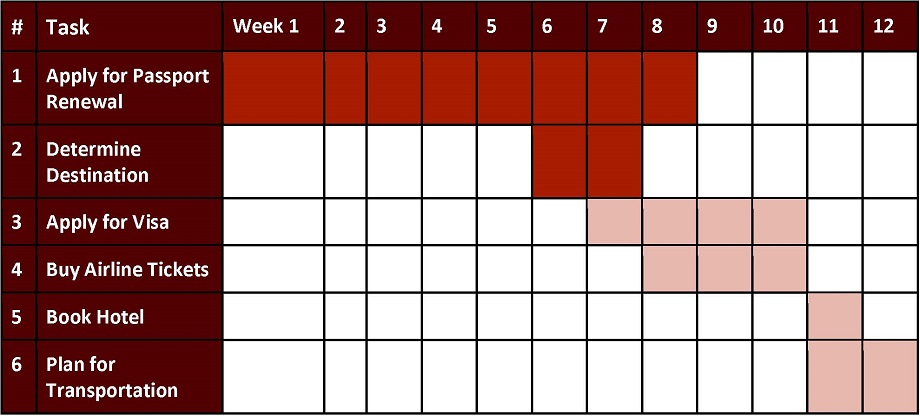

Gantt charts are a way of visually depicting the timelines of tasks within a planned project. They are created by using the table format. Typically, the columns represent units of time such as weeks, days, or even months, depending on the duration of the project. Each row represents a specific task or sub-task, presented in order of anticipated completion. Sometimes complex Gantt charts may also depict subtasks within other tasks, as well as how tasks are dependent on each other. Consider the following simple example of a Gantt chart in Figure 18.1, which gives the steps in planning an international trip.

Figure 18.1[1] is a simple Gantt chart where the length of the tasks in weeks has been determined by factors such as the average time for passport renewal. If the actions were to take place over a shorter period of time, it would be more practical to include dates with increased frequency. In addition, this chart only presents a relatively simple outline of tasks. For instance, the task of buying airline tickets could be broken into multiple steps or subtasks, including looking at specific websites, trying different days and nearby airports, and so on.

Note: Darker cells indicate completed tasks, while lighter cells indicate tasks yet to be started.

The following list presents a series of thoughts concerning the tasks and their timelines, and how they may overlap or need to wait for a previous task to be finished. These logical steps are necessary to consider as Gantt charts convey the expected duration for each task.

- Task One. Several weeks are allotted for renewing a passport, which, under normal circumstances, takes 6-8 weeks.

- Task Two. It is possible to determine the destination of the trip even before the passport returns, hence that task operating concurrently with passport renewal.

- Task Three. However, you would need to wait for the passport before applying for a visa. (Depending on your destination, obtaining a visa ahead of time may or may not be necessary.)

- Task Four. Airline tickets might have to wait until the visa is confirmed or may need to be purchased before applying for the visa, depending, again, on the destination.

- Task Five. Since changing flights a few days earlier or later may change ticket prices, and since some flights may only operate on certain days of the week, it is best not to book a hotel until after tickets have been bought.

- Task Six. Finally, the location of the hotel and its proximity to the areas you are interested in would strongly determine whether you rented a car, relied on public transportation, budgeted for a Lyft or Uber, or walked while visiting.

This Gantt chart also lets viewers know the status of the tasks by using colors and shades purposefully. In Table 18.2, the creator used darker colors for completed tasks and lighter colors for work yet to be completed. You may also consider using colors or shades to indicate which team member or group is working on a particular task or if a task is in-progress.

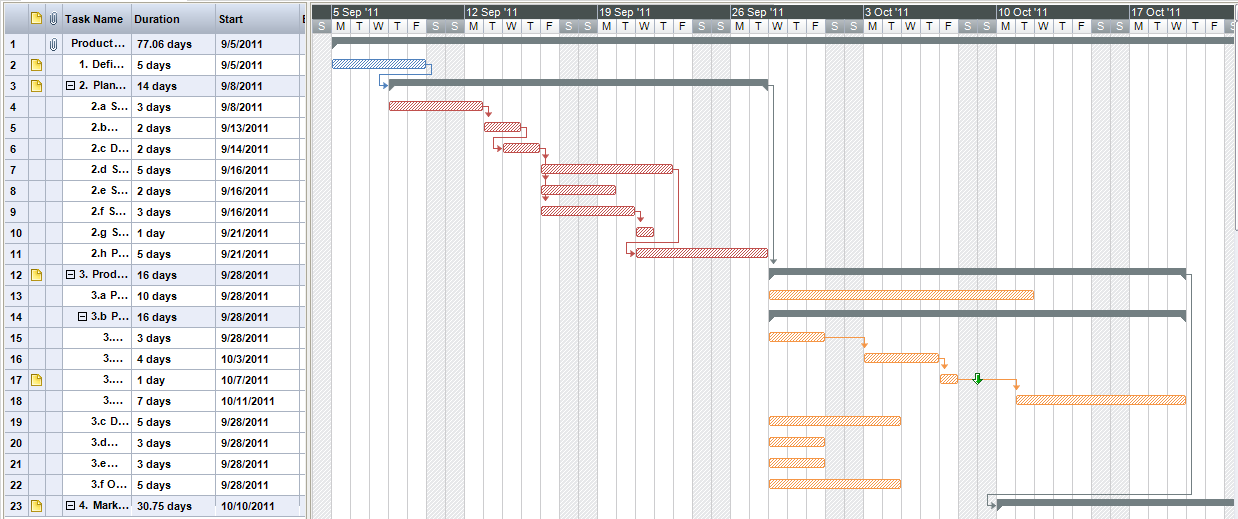

Here, in Figure 18.2,[2] is an example of a more complicated Gantt chart with lines indicating task dependencies on each other, and organizations and colors depicting how larger stages are broken down into subtasks.

Additional Proposal Elements to Consider

- Decide what graphics to use to illustrate your ideas, present data, and enhance your pitch.

- Include secondary research to enhance your credibility and the strength of your proposal.

- Choose format. Is this a memo to an internal audience or a formal report to an external audience? Does it require a letter of transmittal?

This text was derived from

Last, Suzan, with contributors Candice Neveu and Monika Smith. Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Kalani Pattison, “Gantt Chart for Planning an International Trip,” 2020. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

- Matchware Inc., “MindView-Gantt Chart,” Wikimedia Commons, May 27, 2013, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MindView-Gantt_Chart.png. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

Professional document created by an organization or company that asks individuals for proposals in response to a specific situation or problem.

Introductory letter at the beginning of a formal report signalling the movement of the report from the creators to a (usually administrative) reader.

Graphic that visually depicts timelines of tasks within a planned project; commonly used in proposals and progress reports.