1. Mass Capture as a Technology of Non-citizenship

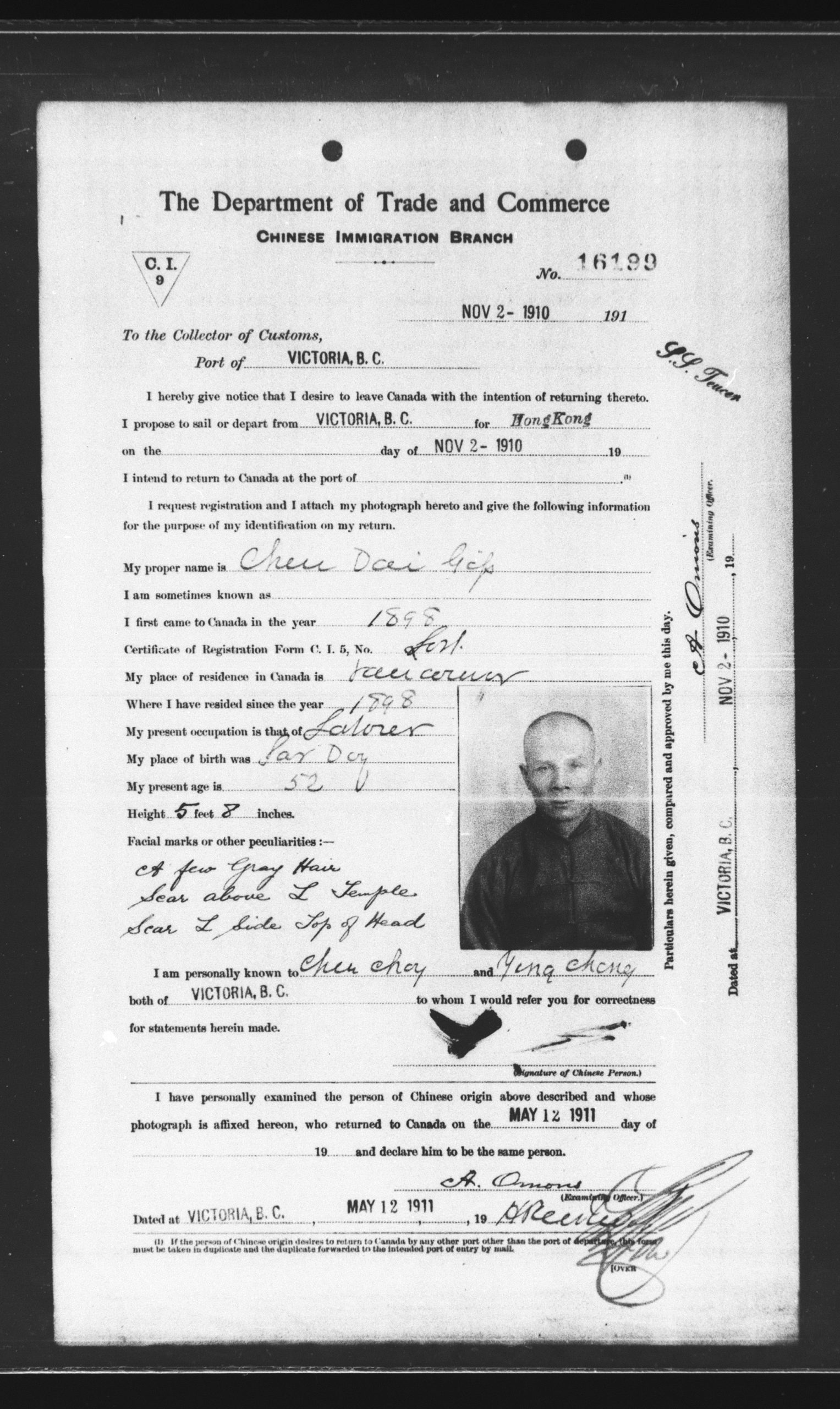

On 2 November 1910, Chew Dai Gip was a labourer residing in Vancouver, BC, when he applied for a CI 9 in order to sail on the SS Teucer bound for the Port of Hong Kong. He had been in Canada since 1898 and was fifty-two years old. He had lost his CI 5 certificate. He measured five feet eight inches tall and was noted as having “a few grey hairs,” a scar about the left temple, and another scar on the left side at the top of the head. We don’t know how he got these scars. But we do know that he was known to Chin Choy and Ying Chong. We know that he did not know how to write his name, because unlike the majority of men who boarded the SS Teucer with him, he could only make a swipe of ink where his signature should have been. He returned to Canada on 6 July 1911. We know these things from CI 9 no. 16199 (fig. 1.1). He was among thousands who applied for permission to temporarily leave Canada in 1910, and among the more than 41,000 who made this same application, identification photograph in hand, between 1910 and 1953. What is the relationship between this man and the other migrants who applied in this way? What is their relationship to these documents and to the state that produces them? Each certificate can be read on its own, but each one is also connected to thousands of others, and to a system of identification and discrimination. Thinking about the whole of the CI 9 archive as more than just a series of individual parts, as more than just one certificate after another, means thinking about it as a system. It is this systemic nature that marks the CI 9s as a technology.

Mass capture, manifested in the CI 9 system, is anchored in the earliest etymologies of the technology. Emerging from post-classical Latin technologia and Hellenistic Greek τεχνολογία, “technology” refers to a “systematic treatment,” and in particular, “a systematic treatment of grammar” (OED). Grammar maps the relationships between words. Technology systemizes those relationships. To understand mass capture as technology is thus to take up how mass capture systemizes the relationships between units of articulation. The CI 9 is an expression, repeated over and over again, of a systematic relationship of exclusion premised on hyper-visibility. The non-citizen is anything but invisible. They must remain always within the view of the state. This visibility is systematized. It is a technology precisely in that it systematizes the rules of relation.

The system of identification generated by the CI 9s ordered relationships between migrants and the state, and between one migrant and another. It made one migrant known by demanding to know who else knew them, thus implicating others in the project of identification while also creating an elaborate map of social networks between migrants. This project of ordering is a grammar. Mass capture is not divorced from contemporary forms of technology, but it is first and foremost a system – a treatment of something that is systematic and rooted in grammar. Indeed, even though it may seem far removed from contemporary technologies of surveillance, grammar is actually central to the latter. Thus, at the heart of Philip Agre’s pivotal theorization of surveillance and capture in computing sciences are what he identifies as “grammars of action” (1994, 102). For Agre, grammars of action allow systems of capture to be replicable such that human activities form “lexical units” that can be sequenced and ordered (108–9). I will discuss grammars of action in more depth later in this chapter, but for now, it is important to note that, as Agre writes, “the practice of constructing systematic representations of organizational activities is not at all new, nor is it inherently tied to computer systems development … it can be valuable in itself, even without any computers” (108). That is, capture, as a technology bound to a grammar, does not need computers. But it does need bodies.

Before there can be grammars, there are bodies through which these grammars are expressed. Further, the grammar of mass capture only works on bodies that are already captive. This chapter theorizes mass capture as a double formation that is both documentary and corporeal. In current scholarship, there are two existing uses of the term “mass capture,” and both are central to how this book understands the ways in which non-citizens are produced. First, in work on privacy and new media, mass capture has been used as a term to describe the ways in which personal data is stored and manipulated for corporate or state interests. I call this documentary mass capture. Second, in the biological sciences, particularly in the study of wildlife management, techniques for capturing large numbers of animals – such as fencing, nets, traps, and so on – are described as mass capture. This scholarship focuses on mass capture as a form of physical entrapment.[1] I call this corporeal mass capture. Although there has not been any overlap between the two uses of this term, in my project they are entwined. Together, documentary and corporeal forms illuminate the workings of mass capture as a technology for producing non-citizens.

Before turning to detail these two formations of mass capture, I want to emphasize that Chinese migrants were indeed non-citizens. In thinking through the experience of pre-1947 Chinese migrants in Canada as one of mass capture, it is crucial to remember that the legislation that put the head tax system into place was not simply about restricting immigration. It is a mistake to understand the Chinese migrants governed by the Chinese Immigration Act as immigrants in the sense that we would use that term now. As I note in the introduction, Canada explicitly identified desirable immigrants as “emigrants.” Emigration agents (not immigration agents) were stationed throughout Britain and in “strategic” parts of Europe beginning from at least 1869 (LAC 2020). Emigrants were seen as future settlers. In contrast, immigrants were clearly marked as undesirable. Indeed, the 1906 Immigration Act was unambiguous in its objective: to give the Department of Immigration the tools it would need to regulate the entry of “undesirable immigrants” (Kelley and Trebilcock 2010, 138). Thus, a quirk of settler-colonial terminology obscures the truth of the Chinese Immigration Act as legislation dedicated to the project of refusing Chinese migrants permanent entry into Canada.

Insofar as it was more restrictive, punitive, and focused, the Chinese Immigration Act is an intensification of the Immigration Act. Where the latter was more broad and less specifically racialized in terms of its target, the former was explicitly directed at one racial group. This specificity owes something to the related contingencies of the settler-colonial state’s clear desire to import substantial numbers of labourers from China, and the fact that China, unlike India, was not part of the British Empire and thus not afforded the dubious niceties of Commonwealth membership. As revealed by Radhika Mongia’s work on the crisis engendered by the arrival of Indians on the Komagata Maru, the fact that Indians were technically British subjects meant that Canada could not simply exclude them in the way that they could Chinese migrants: “the discourse of the liberal state made it exceedingly difficult to distinguish among subjects of the British Empire” (2003, 208). Excluded from the only form of citizenship available to Canadians at this time, that of being subjects of the empire, Chinese migrants presented a crisis of a different sort.

It was a crisis of presence, in which Chinese migrants were actively recruited to come to Canada, but deeply unwelcome as potential settlers. Chinese migrants were necessary for the work of settlement: building the railways, but also a range of other labour-intensive undertakings including fisheries, canneries, bush clearing, and, on the domestic front, laundry and cooking in remote work camps. As one of the commissioners of the 1885 Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, Sir Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau, makes clear in his submission: “cheap labour in a new country is absolutely necessary, and we should have the cheapest labour we can get” (Canada 1885, cii). Five years after this report, in June 1900, the House of Commons sat through a sweltering Ottawa summer night debating amendments to the Chinese Immigration Act that would result in raising the amount of the head tax. After several hours, William Cameron Edwards, member of Parliament for the riding of Russell in Ontario, asked a simple question: “Now what is the purpose of this legislation? Is it for the purpose of excluding Chinese from Canada, or is it for the purpose, in an indirect way, of collecting taxes from them?” (Canada, Parliament, Debates 1900, 8166). The response came from Uriah Wilson, member of Parliament for the riding of Lennox, Ontario: “It is to keep them out” (ibid.). Twenty-three years later, Wilson’s statement would finally be realized.

When the Chinese Immigration Act was amended in 1923 so that Chinese immigrants were excluded from entering Canada altogether, the true objectives of this legislation were revealed. Although it may seem obvious now, I wish to reiterate: the Chinese Immigration Act was never intended to enable Chinese migrants to settle in Canada. The act legislated a tax for the ostensible purpose of discouraging Chinese migrants from coming to Canada. From 1885 to 1923, it allowed Chinese migrants to come to Canada for a fee. This amount was initially set at $50 per “head” and was increased through subsequent amendments such that it rose to $500 by 1904. Although the increase in the fee was supposed to curb the number of migrants entering, as I argue in “Rereading Head Tax Racism” (2002), it is not at all obvious that limiting Chinese migrants was the true intention of the head tax either. Importantly, Canada’s head tax legislation, unlike Australia’s, dropped a clause on tonnage (stipulating the number of Chinese passengers per tonne of cargo on any given ship). The lack of a tonnage clause suggests that this legislation may have been a savvy political move, whereby working-class voters would be pacified by the appearance of government action even though there would be no practical effect on the number of Chinese migrants entering Canada. The census numbers show that the number of Chinese migrants to Canada rose throughout the head tax years (ibid., 73). What is more, despite surges in the emigration of white Europeans to Canada throughout this period, “the ratio of Chinese to the total population did not decrease. In 1881 out of a total population of 49,459 in British Columbia, there were some 4,350 Chinese. In 1901 the population of the province totaled 177,272, of whom 15,942 were Chinese” (Campbell 1923, 51). Thus, for a time, the Canadian government had it both ways: the state relied on inexpensive Chinese migrant labour in order to construct the railway and a few other major projects, while at the same time claiming to be restricting that very influx of migrants. However, once those projects were completed, the migrants were no longer a benefit, just a political liability. The outright exclusion of 1923 reveals not only a callous attempt to exploit and then discard Chinese migrants through successive amendments of the Chinese Immigration Act, it also illuminates the tragedy of mass capture. These men, women, and children remained caught in a state system that sought to deny their presence by constantly drawing attention to the fact of their exclusion from citizenship.

Denying citizenship to a specific population necessitates an elaborate structure of capture. Capture is central to exclusion. The state cannot exclude those it does not apprehend. The state has to make knowable the Chinese migrants residing within its borders. To do so, it must document them.

Documentary Mass Capture

As the sheer quantity of information collected on the CI 9s makes plain, the state obsessively documented the lives of individual Chinese migrants on a level that was, at that point, entirely unparalleled in the history of Canada. Here, there are over 41,000 people whose individual photographic, biographical, and physiological features have been extracted and recorded. In contrast, throughout the head tax years, there are no parallel records of citizens residing in Canada and certainly no system that compares with the CI 9s for tracking the comings and goings of British citizens. There are a handful of individual passport applications, but there is no systematic record of each and every citizen. The enormous scale of the records we have of non-citizens set against the paucity of the records we have of citizens reveals a paradox of the technology of non-citizenship: the state must capture those it wishes to keep out.

This capture takes both physical and documentary forms. Documentary mass capture turns on the acquisition of vast quantities of information. In understanding individualized personal information as a site of mass capture, I draw from legal and activist work on mass surveillance. Specifically, Jennifer Lynch, senior staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), has consistently used the phrase “mass capture” in her writing on the FBI’s use of a massive facial recognition database that draws on identification photographs submitted by US citizens for the purposes of acquiring a driver’s licence, passport, or visa. This database is part of the FBI’s Next Generation Identification (NGI) biometrics database. In no small part because the database tracks citizens who have not been suspected, much less convicted, of a crime, the EFF continues to push for greater transparency and oversight in terms of the construction and uses of this information. Lynch refers to the acquisition of these photographs as mass capture. For example, in her testimony for the US House Committee on Government Oversight and Reform Hearing: Law Enforcement’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology, she states, “Facial recognition allows for covert, remote, and mass capture and identification of images – and the photos that may end up in a database could include not just a person’s face but also how she is dressed and possibly whom she is with” (Lynch 2012b, 15–16). Although “mass surveillance” is the phrase most commonly used in relation to concerns over privacy and its breaches, I hang on to Lynch’s phrasing because it evokes a specific logic of capture that ties back to pioneering work on the intersection of computing and surveillance by Philip Agre.

The logic of capture, as theorized by Agre, lies at the heart of my thinking on mass capture as a documentary practice. In a groundbreaking article published in 1994, “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy,” Agre differentiated between conventional approaches to surveillance, which rely on visual models and metaphors stemming largely from the panopticon, and surveillance as capture. For Agre, the work of capture is underpinned by “grammars of action” that break down a series of activities into discrete and replicable units. Agre notes that “capture” is a “term of art” amongst AI researchers and “refers to a representation scheme’s ability to fully, accurately, or ‘cleanly’ express particular semantic notes or distinctions, without reference to the actual taking in of data” (106). As Wendy Chun explains, “an AI program has successfully ‘captured’ a behavior when it can mimic an action – like a typical retail transaction – without having to sample the actual movement. It works, in other words, when it can ‘pass on’ data because data is not necessary” (2016, 59–60). Agre gives a number of examples of grammars of action: accounting systems; toll highway collection schemes; waiters in a restaurant using automated systems in order to convey orders to the kitchen; and so on (1994, 109). These are systems where human activities can be represented as specific and replicable units so that the data itself moves cleanly across the system. Long before the creeping normalization of social media, “smart borders,” and phones that we turn on and unlock with the touch of our fingertips, Agre understood that surveillance was about data and that data was about capture. Furthermore, capture for Agre is not a form of surveillance that relies on seeing something. Rather, it attends to a pattern of behaviour and the systems whereby these patterns can be codified.

For Agre, the capture model is deeply informed by linguistic metaphors. He notes that “the verb ‘to capture’” is “employed as a common term of art among computing people” (1994, 106), and extends this use to understanding the idea of grammars of action. Grammars of action treat human activity “as a kind of language … for which a good representation scheme provides an accurate grammar” (108). Capture is a grammar governing the relations between actions rather than words. Capture understands discrete actions as functioning like words in a sentence. Each word has a function but each one is also replicable and coded as a part of a sentence. Mass Capture builds on this work by using Agre’s theory to understand a historical instance of capture and its implications for understanding citizenship.

The CI 9s are a grammar of action. They reveal a system of information capture governing the relationship between one non-citizen and another, and between non-citizens and citizens. Each step of the process is a unit in a grammar of action: getting an identification photograph taken at a studio; cropping that photograph so that it will fit onto the form; going to the office of the immigration agent; completing the form through an interview with an immigration agent through a translator; signing one’s name on the form; tucking that form into one’s belongings and taking care while travelling so as not to damage or lose it; returning to Canada with it; requesting re-entry by convincing the agent that you really are the person the form declares you to be. Every one of these actions is governed by rules of relation. Together, these rules are, precisely in Agre’s conception, “a kind of language … a good representation scheme” that provides an “accurate grammar” that produces the Chinese migrant as a non-citizen (1994, 108).

In this representation scheme, the state captures the non-citizen through methods that are derived from the treatment of criminals. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, as Allan Sekula and John Tagg track, the advent of identification photographs, imbricated with the collection of statistical information on their subjects, produced a system of criminal identification that models most of the identification apparatuses that are still in use today. For Tagg, the use of identification photographs coincided with the introduction of British police services and was central to “the complicity of photography in this spreading network of power” (1988, 74). In form and content, the criminal records of Tagg’s study are similar to the CI 9s that would be produced thirty years later in Canada. Like the records for criminals, the CI 9s were forms that bound the identification photograph together with a range of biographical and biometric information. The photograph alone was not sufficient, and could not be entirely believed: it needed to be reinforced through complementary statistical knowledge. Sekula observes that the instrumentalization of photography, particularly for policing, offers “plentiful evidence of a crisis of faith in optical empiricism.” Instead of a purely “optical model” there emerges a “truth-apparatus” where the “camera is integrated into a larger ensemble: a bureaucratic-clerical-statistical system of ‘intelligence’” (1986, 16). This system or apparatus was imported almost wholesale into the tracking of Chinese migrants in Canada in the CI 9 system.

Although it is not surprising that the CI 9 system criminalizes migrant bodies, recall that none of the migrants were captured in this system because the state believed them to be criminals. They had not yet committed any crime. They were merely attempting to cross a border and to travel from where they lived and worked to where they were born or had family and friends. Put this way, such a trajectory of movement could describe the travel itineraries of the vast majority of diasporic peoples. The value of observing the similarity between a prison record and a travel record lies in seeing how we have normalized the repressive methods that are now part of cross-border mobility for citizens and non-citizens alike. As I will discuss in the next chapter, such repressive systems are, not surprisingly, doomed to vulnerabilities and failure. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize the forms of state repression and the ways in which they ostensibly work to differentiate varying categories of criminality and citizenship, even though they also conflate these very distinctions. These systems break down not only because people cannot be perpetually and constantly tied to their documents, but also because they expand outward in order to capture larger and larger groups of people. That is, the bureaucratic-clerical-statistical system of intelligence that Sekula tracks in terms of criminal identification is also the same system that is leveraged against Chinese migrants in the CI 9 system, which is itself the same system that captures any passport holder today.

Part of the value of Agre’s theorization lies in the way it denaturalizes a series of actions that may now seem completely unexceptional. In the twenty-first century, so much cross-border travel has been routinized. The presentation of standardized documents, manufactured under the terms specified by international bodies such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which determines the standard for international passports, may now be taken for granted. But in 1910, when the first CI 9s with attached identification photographs were sent out into the world, this system was relatively novel. It was part of a long process of inventing the systems and rules that would govern how different kinds of bodies would be permitted across different kinds of borders. The notion of difference is, of course, key. If all bodies were equal, and if all borders were equal, then this system would be unnecessary.

The demand for documents of identification at a national border has a long history of being unevenly applied to those who are considered foreign. In his study of the invention of the passport, John Torpey follows the rise of increasingly stringent border controls issued by the Constituent Assembly in post-revolutionary France. In 1791, the Assembly passed legislation that “upheld a ban on departures from the country and enjoined those who had left after 1 July 1789, to return within one month” (2000, 27). Although the law was weak and nullified after a month, “the revolutionary leadership regarded the emigres as potential enemies of the revolution in league with the King, reactionary priests and nobles, and foreign powers – as a profound threat to its survival” (ibid.). The consolidation of the passport as a document of border control in eighteenth-century France thus emerges at the same time as the idea of the foreigner. As Torpey is careful to point out, because of the Constituent Assembly’s fears of political instability, “the term ‘foreigners’ therefore applied as much to those who opposed the revolution, regardless of their ‘national’ origins, as it did to persons not of French birth” (28). The subjection of those who are considered foreign, no matter how their foreignness is defined, becomes more and more rigorous with the stabilizing of the French republic. Thus, in 1912, the French parliament passed a new law that “focused on control of ‘nomads’ (itinerant persons and groups) and the vagaries of their existence. While the law ignored the question of nationality and theoretically applied to all ‘nomads,’ it was in fact directed at foreigners” (108). The new law required those identified as nomads to acquire identity documents that used biometric information including fingerprints and photographs. These documents, “‘carnet des nomades,’” target “the mobile non-national, the inscrutable outside within,” and “helped to constitute people of different countries as mutually exclusive ‘nationals’” (ibid.). The passport comes into being because of fears of foreignness and becomes a durable convention once foreignness itself is identified as distinguishable by race and ethnicity.

Unlike the carnet des nomades, the CI 9 system was leveraged against only one specific group of foreigners, Chinese migrants. And unlike passports, which articulate a relationship between one citizen and another, the CI 9 captures the relationship between a non-citizen and the nation where he or she lives and works, for decades, without the rights and privileges of citizenship. Agre’s theory of capture shows how the CI 9 system was not just about differentiating one migrant from another. Rather, it was a system of identification premised upon the logic of capture.

While Agre’s theory comes out of a meditation on contemporary technology (computers), his model of capture, and in particular its manifestation as a grammar of action, is a very useful way to understand the implications of mass data collection in an era that predates modern computing systems. I do not dismiss the importance of computing technology to Agre’s thinking. But I propose that we can understand technologies that precede the advent of modern computing as conceptually related to it. As the idea of grammars of action suggests, capture is not just about machines recording and storing data, but also a complex negotiation of replicating and representing a range of human activity.

Further, the concept of “information processing” emerges at precisely the same historical period as that of the introduction of the identification photograph requirement on the CI 9s. Agre identifies the rise of information processing as connected to the changes in workplace efficiencies in the era just prior to the First World War: “The first methods for representing human activities on computers were derived from the work-rationalization methods that industrial engineers had been developing since the 1910s. Hence the phrase ‘information processing’: the idea was that computers automate a kind of factory work whose raw material happens to be information rather than anything physical or tangible” (1998, 33). Processing information was a human activity arising out of the use of information as something that could be shaped, sorted, and managed.

The technology of capture is not simply a matter of having the necessary hardware and software, but also one that is imbricated within the social world that uses it. As David J. Phillips contends, “Technology is culture made obdurate. It embodies, fixes, and stabilizes social relations” (1998, 248). Phillips further argues that “technological systems not only secure and fix social relations; they are products of social relations” (ibid.). Technology is not abstracted from the social and cultural world that produces and uses it, and neither is the information that this technology processes. “Information is not an industrial material or a mirror of a pre-given reality,” writes Agre. “It is, quite the contrary, something deeply bound up with the material practices by which people organize their lives. Computer systems design will not escape its associations with social control until it cultivates an awareness of these material practices and the values they embody” (1998, 57–8). Systems embody material practices, but they also carry within them a history of their emergence. Even though computing systems may seem perpetually new and constantly updated, Agre argues that it is crucial to recognize that they have specific histories. He understands computing as a “representational practice”: “At stake is the sense in which a technical field has a history: what it inherits from past practice, how this inheritance is handed down, the collective thinking through which the field evolves, and how all this is shaped by the institutional contexts within which the work occurs” (57). Indeed, before the kind of information processing that Agre examines, there were the elaborate management and accounting systems used by US and British colonial slaveholders, which converted labouring bodies into forms of data for tracking and reporting. “Slaveholders left behind thousands of volumes of account books,” revealing, Caitlin Rosenthal observes, an “obsession with data” (2018, 2). Technological systems are deceptive in their seemingly perpetual newness: they should also be understood as habitually old and palimpsestic, in that they retain the traces and structures of that which precedes them.

Part of this history attends to the connection between computing and surveillance. Even though, as Simone Browne (2015) makes clear, surveillance must be understood as fundamentally shaped by race and this racialization precedes the rise of computer, computing itself is bound to surveillance from its inception: “Ever since the rise of organizational computing in the 1950s, social imagination has always associated computing with surveillance. The reasons for this association are clear enough: computer systems analysis and design promptly took up and generalized the methods of rational administration that organizations had developed throughout the modern era [Clement 1988]. The technical aspect of ‘algorithm’ was assimilated to the bureaucratic concept of ‘procedure,’ and the technical concept of ‘data’ was assimilated to the bureaucratic concept of ‘files’” (Agre 1998, 31). Following the provocations of Agre’s genealogy of computing language, there is a way in which the CI 9s could easily be understood as data (files) developed and acquired for the purposes of creating an algorithm (procedure) whose objective was to screen and track every Chinese migrant arriving and departing the country. My point is not that we should read backwards and look for a kind of pre-history of computing in the CI 9 system. It may or may not be there, but the line between what counts as computational is mutable. Taking this mutability seriously makes visible the kinds of institutional impulses driving a seemingly bland bureaucratic system of data entry and filing. These are the workings of documentary mass capture.

As Agre recognizes,[2] especially in relation to capture and the tracking of individuals and information, computers are not the only part of the mechanism of capture: “The … technology of “tracking is not a simple matter of machinery: it also includes the empirical project of analysis, the ontological project of articulation, and the social project of imposition” (1994, 113). Thus, for Mass Capture, the capture of non-citizens, in the form of large-scale information collection, demands an engagement with the empirical project of analyzing their subjectivity, the ontological project of articulating their status within the nation, and the social project of imposing and securing their status as non-citizens.

Corporeal Mass Capture

Despite the overwhelming mass of the documents that make up the CI 9 system, we must not forget that capture is corporeal in the first instance. Before the non-citizen can be captured in a document or series of documents, they must first endure the physical capture of the ship’s hold, the cantonment, or the camp. The body must first be captured before it can be disciplined by documentation.

My understanding of mass capture as corporeal process is indebted to Christina Sharpe’s theorizing of the ship’s wake and “wake work.” Sharpe outlines the continuing violence of the holding spaces (capture, incarceration) and the holding pattern of historical returns: “We are positioned in the knowledge that we are living in the afterlives of slavery, sitting in the room with history, in a lived and undeclared state of emergency” (2016, 100). The afterlives of this devastation reverberate. The spaces of containment and capture do not disappear with their dismantlement. This wake work demands thinking “through containment, regulation, punishment, capture, and captivity” and the ways in which the hold of the slave ship repeats in the contemporary US prison industrial complex (21). In articulating this wake work, Sharpe asks for more than understanding the painful ways in which the past lives on in the present. She asks for a turn to the future where the violence of the hold can be transformed into acts of “beholden-ness”: “Across time and space the languages and apparatus of the hold and its violences multiply; so, too, the languages of beholding. In what ways might we enact a beholden-ness to each other, later-ally? … How are we beholden to and beholden of each other in ways that change across time and place and space and yet remain?” (100–1). What does it mean to be a later-ally? To be allied in the aftermath means, for Mass Capture, to find the connections between Blackness and the subjectivity of non-citizenship, and to locate in those connections the intersections and resonances between captured Black and Asian bodies.

Falling historically after and figuring later than slavery, Asian labour offers a site of later-alliance. While “slavery was not singular [but] rather a singularity” (Sharpe 2016, 106), indenture is beset by multiplicity. It ranges from textbook indenture to what I think of as “near-indentured” labour, such as railway workers who were technically free but also contractually obligated in ways that left them so deeply indebted for the costs of passage and materials that their debts were nearly impossible to pay off. As such, the conditions of Asian labour vary, and the countries from which indentured labourers were drawn are also diverse. The history and experience of South Asian indenture varies significantly from that of East Asian indenture. Likewise, the experience of Asian labourers working on the Canadian Pacific Railway was significantly different from that of Asian labourers digging in the guano in Peru. And yet, as Lisa Lowe outlines in The Intimacy of Four Continents, there were “often obscure connections between the emergence of European liberalism, settler colonialism in the Americas, the transatlantic slave trade, and the East Indies and China trades in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century” (2015, 1). Such intimacies do not erase differences, but rather insist upon the power of those differences to make visible the violence of colonial erasure.

Although there is little evidence to suggest that the Chinese migrants who travelled to Canada were subject to the same brutal conditions as those who were bound for Peru, it is also the case, as the example of the Bald Eagle below shows, that differently bound groups of Chinese workers are not completely divorced from one another. They share something in their treatment at the hands of settler-colonial societies that demanded their labour but refused to grant them citizenship. I think of what they share as trans-oceanic intimacy that hinges on the complexity of the Chinese migrant labourer’s relationship between freedom and unfreedom. Despite the elaborate taxonomies that differentiated one Chinese labourer from another – taxonomies that are intent on separating migrants from each other – I do not want to lose sight of the relationship between those labourers who were, for example, bound for Canada, and those bound for Peru. The Chinese “coolie” remains a densely complex figure. It is a mistake to simplify and flatten this complexity by taking at face value the system of differentiation and regulation put into place by settler-colonial states insistent that they were no longer in the business of slavery. As Persia Crawford Campbell’s exemplary overview of Chinese labour migration throughout the British Empire reveals, there were a number of variations and differences in the conditions of the labour to which Chinese migrants were subjected. For example, in the British West Indies (British Guiana), Malaysia, and South Africa, Chinese labourers worked under a contract system where they held individual contracts with the state (Campbell 1923, 6, 86, 165). In Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the US, Chinese migrants worked under the credit-ticket system in which the migrants were indebted to brokers who recruited them, supervised their work assignments, and monitored and enforced repayment (26–59). It was a system of “debt-bondage” that allowed people such as Colonel Bee, the attorney for the Six Chinese Companies, who were the main brokers of Chinese labourers, to say, “There is not a Chinaman here who comes under a servile contract” (29). Potentially free in theory, the migrants existed in a state of “long-term indebtedness” to their brokers (ibid.). As W. Pember Reeves observes in his preface to Campbell’s book, the credit-ticket system offers only a veneer of virtue: “At first sight a system under which passage-money was advanced to labourers in Chinese ports and repaid by them out of their earnings in the Colonies seems innocent enough. But managed as it was, chiefly by Chinese middlemen, crimps and compradores, it became largely a veiled slave-trade. Labourers were decoyed into barracoons and virtually sold. They were induced to gamble and lose money. They were kept in confinement, not only at points of departure, but at points of arrival” (xii).

The credit-ticket system was innocent of the horrors of the contract system in name only. In practice, many of the abuses of the indenture system continued.

One point of trans-oceanic intimacy lies in the apparatus of the hold. Following, literally, from slavery, ships carrying Chinese indentured labourers were designed to mimic the slave ship. Overcrowding on such vessels was a persistent problem. The British parliament attempted to address this issue by regulating the space required for each Chinese labourer with the passage of the Chinese Passengers Act in 1855, which was subsequently folded, entirely intact, into the 1894 Merchant Shipping Act, thus preserving these regulations throughout the period of the head tax. This act identified any ship carrying “more than 20 passengers of Asian ethnicity aboard” as “‘Chinese passenger ships’ in law” (Choi 2017, 177). Regarding space for Chinese passengers, Section 4 (2) specifies “that the space appropriated to passengers ’tween decks contains at the least 12 superficial and 72 cubical feet of space for every adult on board; that is to say, for every passenger above 12 years of age, and for every two passengers between the age of one year and 12 years.” Setting aside for the moment the definition of adulthood as beginning at twelve years of age, let me simply focus on spatial regulations. Seventy-two cubic feet is about the space of two average kitchen refrigerators. That was the regulated ideal, and in practice, these laws were not observed. Meagher cites Don Aldus’s eyewitness account of the outfitting of a coolie ship in the 1860s (long after the Chinese Passenger Act had been passed):

The bunks for the emigrants consist of two rows of shelves running the whole length of the ship both sides, as well as down the center. These shelves are six feet wide with an eight inch footboard … After the shelves and footboards are completed the next operation is to measure and number each bedspace, allowing each man a [space] … of from twenty to twenty-four inches, the latter being the legal allowance, but it would appear they are not over particular in this matter as they seldom exceed twenty one inches. There is no kind of division between the sleepers – in short each shelf simply represented one hundred and fifty in a bed. (Meagher 2008, 153)

Meagher turns to two other eyewitness accounts that corroborate Aldus and goes on to note that “this arrangement of space per passenger was the norm, at least during the 1860s and 1870s” (ibid.). Long after the contract labour system was replaced with the credit-ticket system (in itself not necessarily a significant improvement, as noted above) and the so-called era of the coolie trade was supposedly ended, the overcrowding of Chinese passengers continued to be a problem.[3] Stowed by being literally shelved, and frequently locked down under the hatches, Chinese passengers were bound by the forced intimacy of the ships’ holds.

Given the conditions aboard, rebellions on these ships were common. Only one month after the start of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Karl Marx wrote in the New York Daily Tribune about indentured labourer rebellions that seemed to be occurring on every ship: “The very coolies emigrating to foreign countries rise in mutiny, and as if by concert, on board every emigrant ship, and fight for its possession, and, rather than surrender, go down to the bottom with it, or perish in its flames” (“Persia and China,” 5 June 1857). In these flames, Marx points to a history of brutality where rebellious “cargo” was frequently locked in the hold and left to perish. Such was the history of the Bald Eagle.

In a collection of sea yarns published at the end of the nineteenth century, a sailor named Herbert Elliott Hamblen (using the pseudonym Frederick Benton Williams) tells of a fellow sailor, an Irishman named Mike Cregan, who conveyed to him the fate of the Bald Eagle, a US clipper ship under the helm of a Portuguese captain and a largely Portuguese crew. Five hundred miles off the coast of Manila, its cargo, several hundred Chinese men destined to become coolies in Peru, made a desperate attempt to take the ship by rushing at the hatch ladders. The crew quickly closed the hatches and shot at the men below, creating piles of bodies four or five deep, but leaving many still alive. However, a spark from a revolver caught fire on the clothes of the dead men, and half an hour later, smoke began pouring out of the fore and main hatches. Through the smoke of burning bodies and the oncoming darkness, the crew got the ship hove to and eventually abandoned the Bald Eagle for their longboats. The hatches were never lifted, and the crew, including Mike Cregan, sailed away with the cries of those burning alive echoing in their ears.

This is not the whole story.[4] I have re-told it only in its barest form. There are many details we do not know, such as exactly when this happened, or how many people were in the hold when the ship was abandoned. It may have even happened on a different ship – perhaps the Norway, or the Sea Witch, or the White Falcon, or the countless others that burned and disappeared in the years of the coolie trade.[5] Even when we do know the names of ships, we usually do not know the names of all the people who made up their cargo. The general registers of immigration only note those who arrived, but not those who perished. We know that there were countless reports of events like this one. We know that the Bald Eagle was not the only ship that perished in this way.

In order to understand the corporeality of mass capture, this book takes what we do know in order to understand the beholden-ness of the entwined demands of memory and for justice that reverberate in the cries of the captive dead. For, as Eduardo Cadava exhorts, “in order to speak in the name of freedom, in the name of justice, we must speak of the past we inherit and for which we remain answerable, we must speak of the ghosts, of generations of ghosts – of those who are not presently living, whether they are already dead or not yet born” (2004, 140). Theorizing mass capture means, in the first instance, dwelling in the discomfiting and haunting space of these deaths, not in order to put these ghosts to rest, but in order to understand how it is that we live with them, and to think through their restlessness as central to the formation of the subjectivity of non-citizenship. Subjectivities do not form in isolation. Any theory of mass capture must emphasize the relationality of diasporic formations. In the nightmares of an Irish sailor about a burning US ship crewed by Portuguese sailors with a cargo of Chinese labourers on their way to Peru to supplant the lost labour of newly “freed” African slaves, we cannot but come to terms with the problem of relation.

The unjust deaths of those murdered in captivity, as Ian Baucom recognizes in his reading of Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation, are not an ending, but the beginning of a memory that stretches across the depths of the Atlantic – and, as I will suggest in this chapter, the Pacific as well. For Baucom and Glissant, the Zong ship is the site of this beginning and this common history.[6] For Mass Capture, the Bald Eagle enables an understanding of the articulation of the poetics of relation in two modes: as an enunciation of subjectivity, and as the forming of a joint that allows movement. Understanding the corporeality of mass capture means exploring the joints, the connections, between the migrant ship and the slave ship that facilitate movement between and across these oceanic histories. This articulation draws out the ways in which the transpacific is not divorced from the transatlantic. In extending a sense of what is shared beyond the waters of the Atlantic towards the Pacific, we can risk seeing the ways in which relation does not mitigate difference, and attend to the claims of those whose cries of terror have not been stifled by the indifference of history.

The wake work of corporeal mass capture is marked by the underwater graves of the thousands of migrants who have perished in ocean crossings across the centuries. It is in the ashes that have become part of the sea. It is in the screams of those burning in the hold that have never been silenced. It is in the waves that return. It is in what Sharpe names the “maximal wake”:

Waves that occur in the wake of the ship move at the same speed as the ship. From at least the sixteenth century onward, a major part of the ocean engineering of ships has been to minimize the bow wave and therefore to minimize the wake. But the effect of trauma is the opposite. It is to make maximal the wake. The transverse waves are those waves that run through the back; they are perpendicular to the direction of the motion of the ship. Transverse waves look straight but are actually arcs of a circle. And every time, every instant that the boat is moving through water it has the potential to generate a new wave. (2016, 40)

In Sharpe’s metaphor, wake work cuts across and behind the forward motion of the hold. Even though the hold of corporeal mass capture seems to move inexorably forward, it leaves behind a series of movements that resonate, that cut transversally, so that its residue refuses the linearity of the ship’s motion.

In the Wake of the Teucer

In the final part of this chapter, let me follow the wake of one particular ship. I began this chapter with a man, Chew Dai Gip, who sailed from Vancouver to Hong Kong on the SS Teucer in 1910. Nearly seven years later, in February 1917, four Chinese passengers were charged with mutiny on this same ship. In the ship’s log for the Teucer, the captain notes on 8 February: “four of the Chinese labourers of the 1st Chinese Labour Corps were this day put in irons under lock and key, for insubordination inciting to mutiny” (BT 165/1663). As archivists at the UK National Archives have uncovered, the Chinese Labour Corps consisted of approximately 50,000 Chinese men who were contracted to serve in Noyelles Sur Mer near Abbeville in southern France during the First World War (Kumlertsakul 2017). The Teucer carried the first contingent of 1,086 men, suffering what were often “extremely rough” crossings and taking part in major battles including the Flanders offensive in 1917, even while enduring significant losses during attacks such as the air attack on Dunkirk in 1917 (ibid.). The story of the Chinese labourers sent to work on the front lines of a war that was not their own reveals the extent of British colonial reliance on contract labour. The Teucer carried some men home, at least temporarily, and then turned around and carried others to war under the guise of labour. In the transport of that labour, in the story of the hold that emerges in a few faint lines in a ship’s log, there is also the wake of resistance.

This mutiny was not a singular event. Nearly half a century before four Chinese men were put into irons in the hold for attempting to secure their freedom, a different mutiny resonated throughout the British colonial bureaucracy. In 1871, the Chinese labourers on the Nouvelle Penelope rebelled and killed the captain and the officers of the ship, but spared the rest of the crew, claiming that they were merely trying to secure their freedom from conditions akin to slavery.[7] Kwok A Sing, a purported leader of the mutiny, was caught and tried in Hong Kong. He made a habeus corpus application. In a celebrated decision, Justice John Jackson Smale, then the chief justice of Hong Kong, ordered Kwok A Sing released and noted in his decision: “A man under unlawful restraint of his personal liberty at sea, as well as on shore, has the right to take life to free himself from such constraint” (quoted in Meagher 2008, 175). Although Smale’s decision was challenged and overturned on appeal by the attorney general of Hong Kong, it was ultimately upheld by the Privy Council. It was a decision that recast mutiny and piracy as rebellion and resistance by ripping away the veneer of freedom that had obscured the true conditions of Chinese contract labour.

There is a line of connection between the rebellions on the Nouvelle Penelope and the Teucer that extends beyond that of ships and the crimes themselves and into story of Teucer as a figure in Greek mythology. Teucer was the half-brother of Ajax. A renowned archer, he fought alongside Ajax in the Trojan War against Troy, and was one of the Danaans chosen to lie in wait in the belly of the famous Trojan horse that allowed the Greeks to win the war. Despite all that he has done, the Greeks refuse to consider him a true hero. In the Iliad, he is mocked by Agamemnon for the cowardice of fighting with a bow and arrow instead of engaging in close combat with a spear or sword – even though Teucer kills far more Trojans than other warriors. What is more, he is considered nothos, or illegitimate, because his mother is a Trojan slave-concubine instead of a Greek. In Sophocles’s play, Ajax, Teucer demands a burial for Ajax despite the prohibition against it rendered by Menelaus. In this demand, Teucer dissents and resists Menelaus’s authority. As Elton Barker notes, the play democratizes the idea of dissent through the figure of Teucer, who “demonstrates the necessity and desirability of dissent as a democratic prerogative” (2009, 14). Refusing the legitimacy of authority that is anchored in cruelty and the persistent silencing of the non-citizen, Teucer models the forms of agency that can be carved out even in the face of terrible loss.

Teucer is not just a dissenting figure, but also one who is denied speech in the political arena because his illegitimate birth renders him, under the Periclean rules of citizenship, a non-citizen. As Mary Ebbott notes, both Menelaus and Agamemnon connect Teucer to non-citizenship when they mock his inability to speak for himself in the assembly: “The taunt that Teucer needs to find a free man to plead his case points to not only the slavery connection but also to restrictions on the right to speak freely (parrhêsia) for nothoi in Athens. Excluded from the political assembly, where the freedom to speak is symbolized by the extension of the right to “whoever wishes” (ho boulomenos), nothoi would easily be associated with a lack of free speech and with the agency with which citizens were endowed. All of these categories can be lumped together as non-citizens” (2003, 46). Teucer has fought for the Greeks, but he is denied the rights and privileges of Greek citizenship. Here, the wake of Teucer’s predicament flows over the Chinese workers who found themselves on a ship bearing Teucer’s name, pressed into serving in a war for a nation in which they have no rights because they are not citizens. Their dissent, a failed mutiny, gestures towards a different kind of silence. Without any right or recourse, they were held below decks, detained in a hold where the only release was to sacrifice their bodies as labourers on a battlefield.

In this state of capture, their resonance with Horace’s depiction of Teucer is also reinforced in the context of Teucer’s displacement. Exiled by his own father for failing to bring back the body of Ajax, he can only return to the sea. Cast away from his only home, he tells his ship brothers:

[verse] Wherever fortune may bear us, kinder than my father,

We shall go, o men and comrades!

Do not despair with Teucer as your leader and as protector,

Surely resolved Apollo has promised uncertain

Future to Salamis in a new world.

O men, who with me often have endured

Worse fortunes, now, banish cares with wine;

Tomorrow we shall set out upon the boundless sea! (Odes)

Despite being silenced and exiled, Teucer is not a pure figure of abjection. After his exile, he goes on to become king of Salamis, a small island near Athens. As Maria Bittarello observes, as a king, Teucer becomes an important mediating figure between the Greeks and the Cypriots:

Extant sources clearly show how Athenian politicians and the Cypriot king Evagoras used the myth of Teucer ingeniously in order to serve their own political interests. Athens needed to secure in Evagoras a precious ally who was going to be useful in her commercial relations with the East as well as in the city’s political relations with the Persian empire. As for Evagoras, he claimed to be a direct descendant of Teucer to gain a privileged position in Athens. Moreover, Evagoras’s claim allowed him to keep his prerogatives as king of Cyprus and satrap of the Persian empire while maintaining a certain degree of independence from the Persian “king of kings.” (2007, 5)

Further signalling the complexity of Teucer’s position, Bittarello follows Teucer’s depiction in Euripides’s Helen, where Teucer is identified as “metoecus (i.e., metic), a term that indicated those who were free people but not full Athenian citizens. Metics lived in Athens, paid an annual tax, and had (limited) civil rights, although they were not allowed to participate fully in political life” (3). Ostensibly free but left without speech or political participation, Teucer as metic illuminates something of the complex position of the Chinese labourers who would be borne “upon the boundless sea” on a ship that bears his name.

Bound and unbound, unfree yet free, the Chinese labourers aboard the Teucer speak through the violence of failed resistance and mass capture. Caught in the hold, and again in the documentary systems (head tax certificates and ships’ logs) that record the fact of their capture, Chinese migrants were subject to forms of capture that were both modern and ancient. Mass capture is a double formation that is documentary and corporeal. It emerges out of captive bodies and the systemic capture of information about those bodies. Working in tandem, corporeal and documentary mass capture make manifest the non-citizen. However, the mass captured do not remain captive. They dissent. They escape. In the next chapter, I will follow how the mass captured unsettle discourses of memory, and manufacture one form of escape.

- See, for example, Gooch (1953), “Techniques for Mass Capture of Flightless Blue and Lesser Snow Geese”; Smuts, Whyte, and Dearlove (1977), “A Mass Capture Technique for Lions”; Marshall (1987), “Maori Mass Capture of Freshwater Eels”; Bamford, Monadjem, and Diekmann (2009), “Development of Non-explosive-Based Methods of Mass Capture of Vultures.” ↵

- I want to pause to meditate on invisibility and disappearance in relation to Agre himself. Agre disappeared sometime between 2008 and 2009. The story of his disappearance appears near the top of the results of any internet search of his name. He had abandoned his apartment and his job as a tenured professor of computing science at the University of California, Los Angeles. His sister filed a missing person’s report. On 16 January 2010, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department reported finding him in “good health and self-sufficient.” But his family remained concerned and were not convinced by this report. Found and not found, safe and not safe, Agre’s disappearance is full of contradiction and irresolution. In working with his writing, it has been increasingly difficult to separate theintellectual legacy from this biographical information. I am not advocating a biographical approach to Agre’s writing. But his disappearance continues to raise questions for me about the unknowable implications of his thinking. In Agre’s disappearance, there is a lesson that I am still trying to learn about what it means to test the limits of knowability and visibility. He left a whole life behind when he disappeared. As an early theorist of the connection between data and capture, Agre’s life and disappearance shine a light on the importance of remembering the bodies that are behind the data. In the case of the CI 9s, this work demands a turn to considering more than the information captured on the forms; a turn to considering the physical bodies that are subject to mass capture, as well. ↵

- Choi notes, for example, that the British consul in Chefoo reported in 1893 a case of a ship overcrowded with Chinese passengers. The ship’s owners, Jardine, Matheson, and Co., “were responsible for the coolie business, [and] protested against the consul’s report as unfair to British trade” (178). Thus, the persistence of the coolie trade, and of overcrowding, is only visible because the owners of the ship protested a consular report about their own violation of the law. ↵

- This story is published as the eighth chapter of On Many Seas: The Life and Exploits of a Yankee Sailor (1896). Hamblen/Williams claims to have overhead Cregan tell the story one night as a reason for his inability to sleep. The structure of the chapter where one sailor tells the story of the bad dreams of another signals the way in which this story circulates as a nightmare that repeats. ↵

- The British experimented first with using Chinese and East Indian labourers in Trinidad in 1806, not coincidentally during the first year that they ended the slave trade. While the experiment was a failure, by the late 1830s thousands of East Indian and Chinese labourers had been transported to the West Indies. The coolie trade, or la trata amarilla, in Latin America thrived largely between the years of 1847 and 1874, although coolie labour was still in use in the region until the late nineteenth century. In 1904, spurred on by the “Rand crisis,” the British reopened the transportation of Chinese contract labour, this time to South Africa. After a series of horrific abuses, an act was passed in 1907 to terminate the contracts. However, still under the administration of the British, coolie labour was in use in the South Pacific islands of Western Samoa and Nauru until the first decades of the twentieth century. See Campbell (1923), Hu-DeHart (1994), and Look Lai (2004) for further details regarding the historical data of this trade. ↵

- As will be discussed in chapter 3, in 1781 the Zong’s captain, Luke Collingwood, attempted to compensate for steering his ship off course and facing supply shortages by ordering drowned over 130 slaves in order to guarantee profit through the collection of insurance money. The insurers refused to pay and the ship’s Liverpool owners sued the insurance company, thus recording in the judicial archives the details of this massacre. ↵

- For a summary of the case, please see Norton-Kyshe, History of the Laws and Courts of Hong Kong (1898, 186–7). ↵