4. Mass Capture and the Grammars of Persistent Representation

Mass capture is a double formation that is both documentary and corporeal. As I outline in chapter 1, mass capture works through the capture of information and bodies, and one form of capture informs and shapes the other. There is no mass capture of Chinese migrants during the period of the head tax and exclusion (1885–1947) without the information apprehended in the once-blank spaces of the CI 9 certificates, and the bodies of the migrants caught within the hold of the ship, and the labour contracts that left them indebted and further ensnared. Yet, as chapter 2 shows, this capture was never total. There is no necessary correlation between the person the certificate claims to represent, and the actual person holding the certificate. Indeed, the absence of a discernible relationship between the anglicized and Chinese names on so many certificates suggests that such a lack of correlation is more commonplace. Although this argument opens up a way to see how Chinese migrants may have turned the CI 9 system against itself, I recognize that it also works against a major part of the argument that I present in chapter 3. In that chapter, I argued for the need to see each certificate as representative of a life. For example, in my discussion of the photographs of the Chinese passengers on the Oanfa, I asked readers to think of each certificate as representing a life and a member of the kinship network of the diasporic passage experienced by those on board that ship. Thus, after questioning the capacity of the CI 9 to represent a life, I insist that it does.

This apparent contradiction reveals a larger problem regarding the authenticity or veracity of the CI 9s themselves. In this chapter, I will address the problem of the realness of these documents, and of the people they purport to represent, by turning to the study of diplomatics, a branch of archival research that emerges in the medieval era but has more recently taken on new dimensions through the work of Luciana Duranti. Citing Peter Herde, Duranti offers the very general definition of diplomatics as “‘the study of documents’” (1989, 14). Throughout this book, I have looked closely at the people caught in these documents, and the processes of their capture, but I have not yet examined the CI 9s as forms in themselves. Building on the work of Duranti, this chapter takes up the problem of the form itself as an object of study. Such a turn resolves the contradiction of the CI 9 as both that which does and does not represent the lives of the people caught within its frame.

The CI 9s do represent the life of a migrant, but these certificates do not always represent the particular life of the person carrying that particular certificate. A diplomatic analysis will show how to understand the truth of these documents as documents. It will also show how an examination of the CI 9 as a document allows us to see more clearly the lives that are captured on the document. While it may seem in tension with my commitment to honour the lives of the people who have been subjected to the processes of mass capture in the CI 9 system, I suggest that focusing on the document instead of the person represented by it actually allows for a return to the corporeal consequences of mass capture. As I will outline in the next section, the certificates attempt to capture a specific kind of truth about each migrant, but what they capture instead is the truth of a process. The CI 9s do not document people. Rather, they document a process that attempted to document people.

The move from person to process is not a shift away from the people who have been subjected to mass capture. It is a move towards understanding more clearly the process of their subjection. As chapter 2 shows, the CI 9s are not a perfect record of each and every Chinese migrant who ever registered an outward journey with the intention of returning to Canada. The records are flawed, not least because of the ingenuity of migrants who may themselves have exploited the system’s weaknesses. Because of these flaws, the CI 9s are not always a reliable genealogical resource. Certainly, many people have already found the CI 9s to be a tremendous resource for finding traces of their relatives. I have no doubt that many more will continue to find these certificates to be a resource for ancestry research. As I have shown with the Lawson family in chapter 3, the CI 9s used in tandem with other resources – such as birth and death registries, newspaper obituaries, and the General Register of Chinese Immigration – can yield a rich portrait of a family through several generations. Nevertheless, unlike the Lawsons, there are thousands of migrants whose presence in this archive will yield little further knowledge.

For example, the baby, “Miss Wong Louie Youe,” in CI 9 no. 20306 (fig. 3.1 in chapter 3) is recorded in this archive, but she is more lost than found. Her birth was not recorded in Canadian registries. Her name on the CI 9 may or may not have been correctly noted. We cannot find her parents. The woman who holds her in the photograph, Mrs Hom See, is also a mystery. But these losses, the information gaps around these women, do not invalidate the truth of their presence in this archive. Understanding their presence as central to the process of mass capture is one way to attend to what remains real about these documents. There was a baby. She was here. Her CI 9 may not be telling the truth of her identity, but it does incontrovertibly tell us that she was subjected to a process that has, in Vijay Mishra’s phrasing, “entered for the first time the regulative history of Empire” (1996, 429). Here, she becomes a subject of history. It does not matter whether she is who the certificate claims. She is here before us now. Despite the loss of her family, the loss of the records that would allow us to find them, her presence persists on this form and in this documentary process.

These documents are representations of the activity of mass capture, the processes to which people were subjected and how these processes made people into subjects of history. Miss Wong Louie Youe enters history because of a discriminatory system of information capture that attempted to make her known to the state. We may not know much about Miss Wong herself, but the document that claims to represent her is richly telling. It tells us that even babies who could neither speak nor write were subjects of mass capture. It tells us that some children were separated from their families and that this separation is plain to see in the documentary record itself. More than anything, it tells us that the CI 9 system was a series of actions and activities indifferently applied to many different people, and that this application enables a persistence of presence. A diplomatic turn will illuminate the workings of this persistence.

Diplomatics as Persistent Representation

Diplomatics is a field of archival study that emerged in the medieval period in response to a rise in the forgeries of administrative-legal documents. It rose in tandem with paleography and, as noted by Duranti (who is widely credited with spearheading the application of diplomatics beyond medieval studies), forgeries did not become a widespread problem until documents were separated from the places where they were kept:

The problem of distinguishing genuine documents from forgeries was present in the earliest periods of documentation, but until the sixth century no attempt was made to devise criteria for the identification of forgeries. Even legislators did not demonstrate interest in the issue, basically because of the legal principle commonly accepted in the ancient world that authenticity is not an intrinsic character of documents but is accorded to them by the fact of their preservation in a designated place, a temple, public office, treasury, or archives. This principle was open to abuse. Eventually, people began to present forgeries to designated records offices to lend them authenticity. Therefore, practical rules to recognize them were introduced in Justinian’s civil code (Corpus iuris civilus) and later in a number of Paper Decretales. (1989, 12)

When documents did not travel, when their authenticity could be guaranteed by their immobility, the issue of authenticity did not arise. It is only when documents began to move, when they were presented to places of juridical or legal import rather than being consulted in those places, that forgeries became a problem. This linking of mobility with suspicion will emerge again in chapter 5 in my discussion of the rise of the passport in relation to the CI 9. For now, it is sufficient to note that the mobility of documents, much like the mobility of people, instigates suspicion.

The movement of documents necessitates their doubling. Appropriately for CI 9s, which begin their lives as doubled documents, diplomatics is etymologically rooted in the idea of doubling:

Both the words diplomacy and diplomatics have their root in the Greek verb diploo (διπλό), meaning “I double” or “I fold,” which gave birth to the word diploma (δίπλωμα), meaning “doubled” or “folded.” In classic antiquity, the word diploma referred to documents written on two tablets attached with a hinge and called diptych; and, during the Roman Imperial period, to specific types of documents issued by the Emperor or the Senate, such as the decrees conferring privileges of citizenship and marriage on soldiers who had served their time. In time, diploma came to mean a deed issued by a sovereign authority, and was extended to include generally all documents issued in solemn form. (1989, 12)

Understanding the CI 9s as a problem of diplomatics locates the problem of their authenticity squarely within their existence as documents that were presented and exchanged in the course of travel, and which were, by their very nature, doubled and folded into the documentary apparatus of the state.

Crucially, diplomatics enables us to disentangle the ways in which the CI 9s can be both authentic as documents, and potentially inauthentic in terms of the people they purport to identify or represent. Duranti draws out the differences between diplomatic authenticity, legal authenticity, and historical authenticity. For her, these three types of authenticity can be totally independent of each other. “Diplomatic authenticity does not coincide with legal authenticity, even if they both can lead to an attribution of historical authenticity in a judicial dispute.” For example, a “Papal brief which does not contain the expression ‘datum … sub anulo piscatoris’ may be legally and historically authentic, but it is diplomatically inauthentic” (1989, 17). Such distinctions are helpful for understanding how any particular CI 9 might be authentic in terms of its diplomatics because all the necessary signatures, countersignatures, and other verifying marks are present. It can also be legally authentic in that it will afford its bearer the right to return to Canada. But, as in the case of Wong Lim Foon on CI 9 no. 22711, discussed in chapter 2, a CI 9 can be historically false because the certificate does not accurately represent the identity of the man it claims to identify.

This differentiation between the diplomatic, legal, and historical authenticity of a document offers a way to understand how each CI 9 is representative of a life, yet not necessarily representative of the specific life that it claims to represent. The CI 9s remain legally authentic in that they “bear witness on their own because of the intervention, during or after their creation, of a representative of a public authority guaranteeing their genuineness” (Duranti 1989, 17). They are also diplomatically authentic documents in that they “were written according to the practice of the time and place indicated in the text, and signed with the name(s) of the person(s) competent to create them” (ibid.). Indeed, the CI 9s in this collection are almost uniformly diplomatically authentic. I have yet to find one that does not include the requisite signatures. The rules to which they had to conform vary slightly over the years, but they are remarkably consistent in their observance of the demands of the form itself. The blanks spaces are filled out. The photographs are attached. The signatures of the migrants are either included or an “x” or a thumbprint is given by those who could not write their own names. But, in terms of their accuracy as documents representing the history of a particular person, they start to fall apart for all the reasons that I outlined in chapters 2 and 3. The agents recording the information did not speak Chinese and relied on translators. There was no consistent system for anglicizing Chinese names. There was no differentiation between surname and given name. The state used the exact same set of numbers for certificates of migrants leaving from Victoria and those leaving from Vancouver, resulting in the existence of thousands of certificates that share a numerical identifier. There were literally two of every certificate number, each representing an entirely different person departing from a different port on a different ship. Thus, Wong Lim Foon had a double. CI 9 no. 22711 also belonged to Ing Yong Lan (figs. 2.2 and 2.4 in chapter 2). Or, in the case of the Lawsons, James Ying Choury on CI 9 no. 17940 was not given his father’s surname and would have been lost to the family, in terms of the records, had it not been for the numerical sequencing of the certificates (fig. 3.20 in chapter 3).

Even though so much of my research has resulted in finding examples where the state failed in its attempt to identify and track each Chinese migrant who ever wanted to temporarily leave Canada, I have also never lost my sense that a given certificate truly does represent a life. In each case, at least one person was issued that certificate and carried it on his or her person. A photograph attached to a CI 9 is an image of a real person. Again, it matters less to me whether or not that photograph is of the person it claims to identify. For the person who is looking for a great-great-grandfather, I hope that it is. But I also do not want to discount the value of these images on the grounds that they may not correspond with the identity of the person on the certificate. As Elizabeth Edwards argues, “it is not what a photograph is of in purely evidential terms that should primarily concern us, but the context in which it is embedded” (2001, 88). The context of the CI 9 demands a way of seeing these images and these documents as more than just the sum of their evidentiary parts. Taken together in their context, the images on these documents uncover the complexity of a process of capture that almost always worked as a process, but often failed as a system. These failures are to be celebrated. Capture was not, and was never, total. That does not mean that the process itself should not be examined. And it certainly does not mean that the presence of these thousands and thousands of migrants, caught within what Leigh Raiford in a very different context calls the “luminous glare” of the state, should not be valued (2013, 1).

Indeed, it is the persistence of the presence of the men, women, and children in these certificates that has held me. This persistence also has a place in diplomatics, in what Geoffrey Yeo calls “persistent representations” (2007, 342). Yeo comes to his theory of the archival record as a persistent representation out of his dissatisfaction with understanding archival records as either evidence or information. Instead, he argues that archival records should be understood as “persistent representations of activities” (ibid.). Building from literary theory on representation, and particularly that of W.J.T. Mitchell, Yeo argues that “records have persistence.” As he points out, not all representations are persistent: “The reflection in the pond, the reading on the speedometer of a car, the unsaved document residing only in a computer’s temporary memory are not persistent.” In contrast, “a persistent representation is one with the capacity to endure beyond the immediate circumstance leading to its creation. Persistence need not imply survival without limit of time. Records may not last forever and decisions may be made to destroy them. But records are persistent in the sense that they endure beyond the temporal ending of the activities they represent. Their durability gives them the potential to be shared and passed on across space and time” (2007, 337). This conception of the archival record as a persistent representation encompasses both the letter and the spirit of what I want to hold in the CI 9s. The latter persist as representations of the actions of a state that engaged in processes of mass capture in order to make and remake, again and again, these migrants as non-citizens. But they also persist as the indelible presence of people whose gazes have endured the destruction of lives and families, even the destruction of the original records themselves. The people on these certificates look back at us across space and time and challenge their viewers to look away.

Taking Yeo’s conception at a remove, understanding the CI 9s as persistent representations is not only a way of distinguishing their value as both evidence and information, but also a way to embrace the endurance of the lives captured in these certificates. Yes, these certificates do represent the activities of a state-sponsored process of mass capture. However, they are more than that. To think of the CI 9s as the representation of a process is also to take up these certificates as a record of what it took to endure this process.

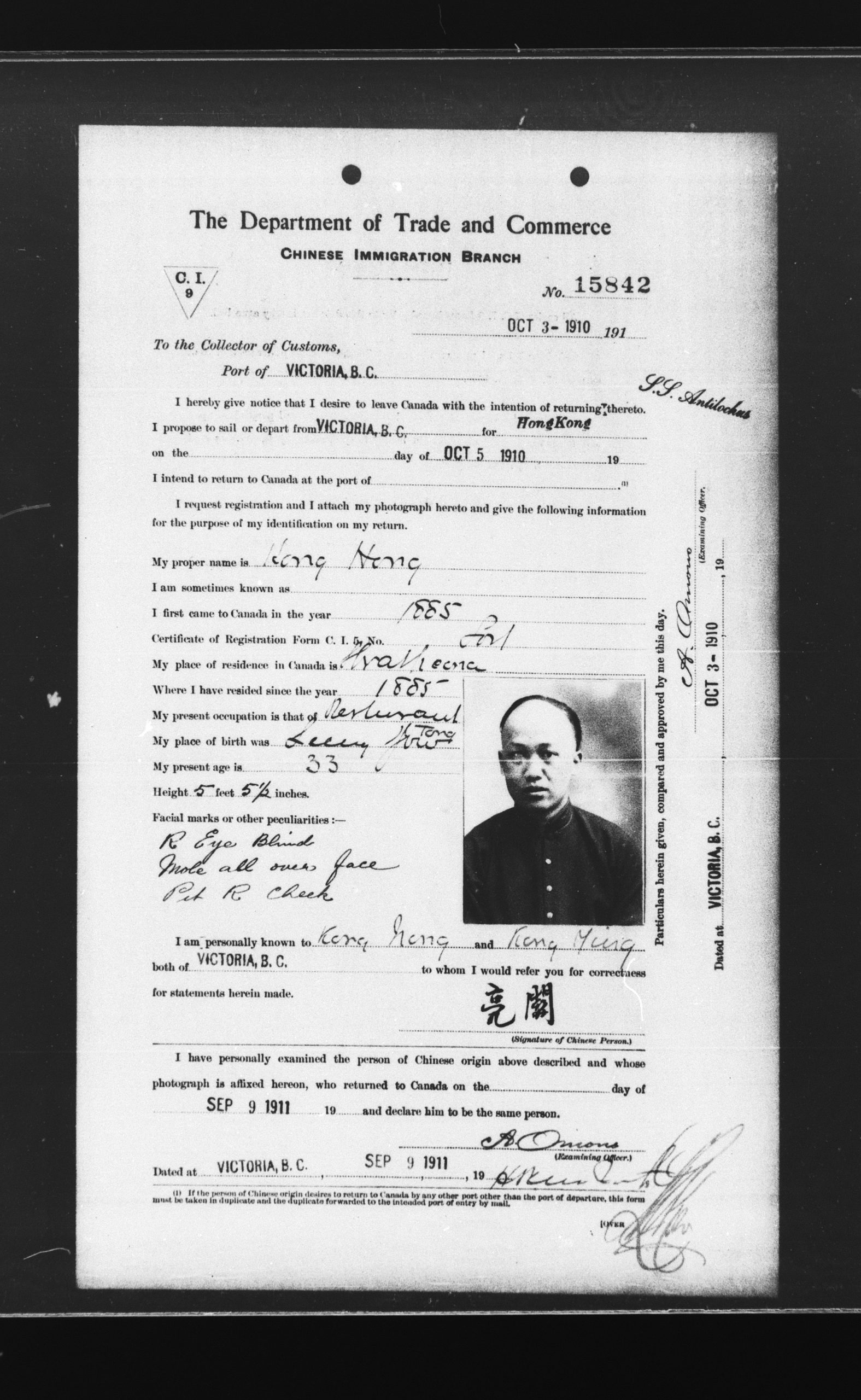

On every CI 9 is a persistent representation of endurance. Take, for example, just one of the many CI 9s that records the presence of a Chinese migrant living and working in Canada for decades. According to the certificate in figure 4.1, Kong Hong, CI 9 no. 15842, first came to Canada in 1885, which was the first year of Chinese Immigration Act. It is not clear whether he lived in one of the parts of Vancouver that were at various times known as Strathcona, or in the town of Strathcona near Edmonton, Alberta. The latter seems more likely as many certificates list Vancouver as a place of residence and other Vancouver neighbourhoods are not listed as separate geographical entities on these forms. He would have been among the first to pay the head tax, but there is no evidence of this payment because his CI 5 has been lost. On 3 October 1910, when he sailed for Hong Kong on the SS Antilochus, he is recorded as being thirty-three years old. That means that he would have arrived in Canada at the age of eight. Was he born in Canada but did not have the opportunity to record this fact on the form because there is no line to indicate place of birth? The CI 9 does not tell us. But it does tell us that he worked in a restaurant, that he returned to Canada less than a year after he left, on 9 September 1911, and that he was blind in the right eye.

What did Kong Hong endure? What must it have been like to live in a small prairie town for so many years? When did he lose the use of his right eye? What did this disability mean for how he made his way in a country that was inhospitable to him, at a time when he would have been frequently targeted by white working-class labourers who saw him as a threat to their livelihoods? As I note throughout this book, the details of each life that are recorded on the CI 9s also often pose as many questions as they answer.

Even if only some of the information on this certificate is true, it is a record of the persistence of Kong Hong’s presence. The exact dates and years might not be correct, but the general parameters of his time in Canada still indicate that he was not a tourist or visitor. He was not passing through or visiting for a few months or even a couple years: he had been here for decades. He might have been born here. In Yeo’s terms, this CI 9 is representationally persistent in that it records activities that endure beyond the instance of the creation of this particular record, and beyond the time of this particular activity (i.e., the tracking of Chinese migrants who left and wished to return to Canada under the auspices of the Chinese Immigration Act). Here, there is the representational persistence of the record as a record, but also a record of the persistence of presence.

These two forms of persistence – the persistent representation and the persistence of presence – work against each other in ways that reveal both the durability of processes of exclusion and the resilience of those who were excluded. Understanding the CI 9 as a persistent representation uncovers the endurance of mass capture – manifested as surveillance in the name of excluding an entire population from access to citizenship – as a process. The certificates are records of a set of activities that clearly target one racial and ethnic group with the sole purpose of their exclusion. But, as records that show the duration of each migrant’s tenure in Canada, they also show the endurance of the migrant’s refusal to be forced out of a country that they helped to build.

The persistent representation captures a continual attempt on the part of the state to exclude Chinese migrants from Canada. And that very same representation illuminates the persistence of these same migrants’ refusal to be removed. More than that, these records show us, at a deeply granular level, how much these migrants could take. We have known generally that Chinese Canadians persisted in their refusal to be forced out of the country, and that they endured tremendous hardship as a result of this endurance. The CI 9s give a sense of just how much could be borne. According to his CI 9, Kong Hong stayed in Strathcona for at least twenty-five years (from 1885 to 1910). For most, if not all, of his life, he grew up, lived, and worked in a country that was profoundly hostile to him.

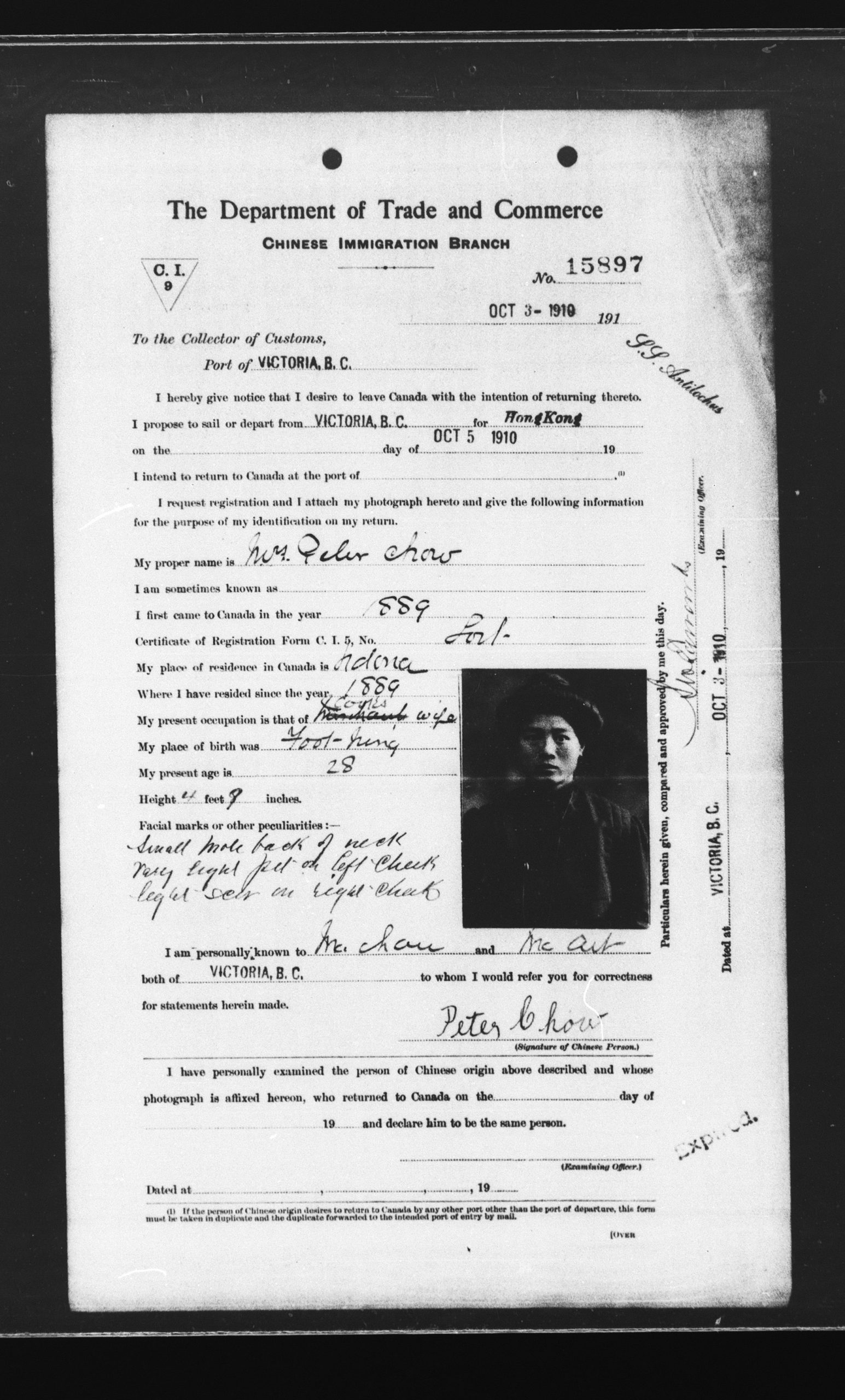

There are limits to endurance. Kong’s CI 9 shows that he did return to Canada. But many did not. There is Mrs Peter Chow, pictured in figure 4.2. She travelled on the same ship as Kong Hong. She is the first Chinese woman to be photographed in the CI 9 archive. Her CI 9 is also a persistent representation and a record of the persistence of her presence. She first came to Canada in 1889. She was seven years old. She arrived as a child in a place that did not want her. She survived the month-long crossing of the Pacific in steerage. She grew up in a country that actively sought to exclude her from having rights of any kind, with the additional burden of being a girl and then a woman enduring the reality of persistent processes of exclusion. She was twenty-eight years old when she left Victoria in 1910.

Her identity is so fully erased that she can only be persistently represented by her husband. Like Mrs J.J. Lawson in chapter 3 (see fig. 3.19), her signature comprises her husband’s name. The agent initially recorded her occupation as a housewife, but crossed that out to note that she is a “cook’s wife” instead. That revision is telling. She is not the woman of a household, but rather a woman whose presence is tied to the labour of her husband. Her ties to commercial cooking, and not the domestic sphere, must be clarified.

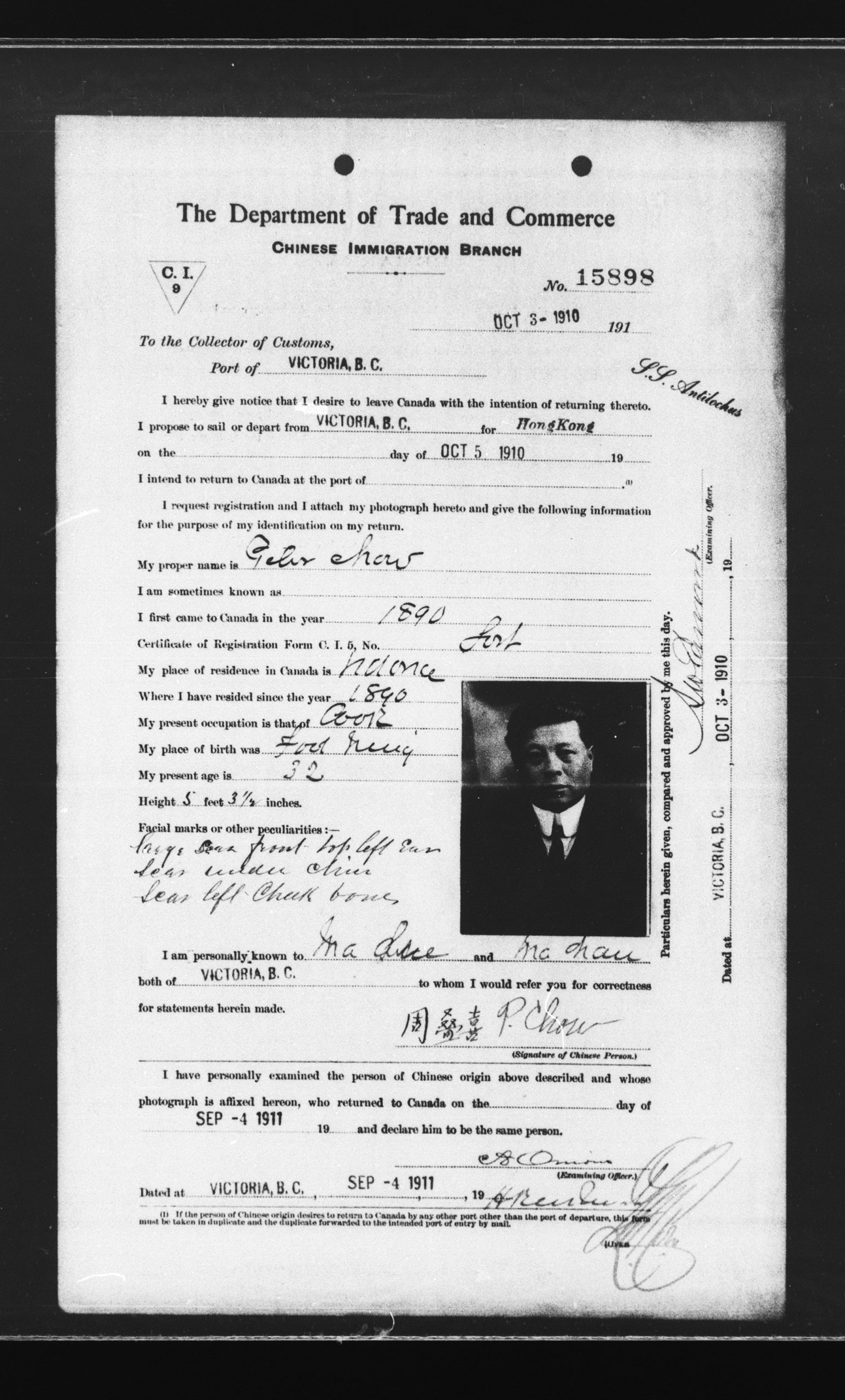

On 5 October 1910, she sailed on the SS Antilochus with her husband, Peter Chow. Like his wife, he too has lost his CI 5. There is no record of their payment of the head tax. There is, however, the record of his return to Victoria on 4 September 1911 (five days before Kong Hong). And there is a record of Mrs Peter Chow’s refusal to return with him. Her certificate is stamped as expired. She had endured enough.

Grammars of Persistence

Philip Agre’s (1994) description of information capture as a grammar of action is particularly useful for its emphasis on the social nature of imposing a grammar onto human activities. Agre’s concept makes room for human interpretation and error, for the kinds of eccentricities and innovations that we have already seen at work in the CI 9 system. Even though the system is full of errors, even though it fails in so many ways as a system of surveillance and identification, it is still a systematic treatment where one group of people, working on behalf of the state, subjected another group of people, Chinese migrants, to a system of information capture with the goal of tracking their movements and activities. I have examined some of the ways that the CI 9 system is vulnerable to error in chapters 2 and 3, and I tried to read some of these errors as more than mere mistakes, but rather as instances of ingenuity, resilience, and resistance on the part of Chinese migrants. These errors and resistances do not mitigate the fact that the CI 9s were a system of capture. Using Agre’s concept of grammars of action allows for an understanding of capture as a technology with social and ideological implications. As he argues,

no matter how thoroughly the capture process is controlled, it is impossible, short perhaps of total mechanization of a given form of activity, to remove the elements of interpretation, strategy, and institutional dynamics. This is not to say that capture is impossible; to the contrary, numerous impressive examples already exist. The point, rather, is that capture is never purely technical but always sociotechnical in nature. If a capture system “works,” then what is working is a larger sociopolitical structure, not just a technical system (Bowers, 1992). And if the capture process is guided by some notion of the “discovery” of a preexisting grammar, then this notion and its functioning should be understood in political terms as an ideology. (1994, 112)

As any habitual user of social media can see, Agre’s recognition of the imbrication of the social with the technical in matters of information capture is prescient and accurate. It may seem obvious to us now that we so frequently use technology as a platform for social engagement and community, but it is still worth explicitly recognizing that technology does not exist in a vacuum divorced from social relation. Long before millions of people in the twenty-first century managed their social lives with a technology founded on a virtual “book” of faces, the CI 9s organized the lives of Chinese migrants based on physical books of their faces. Agre’s recognition of the foundationally social nature of technologies of capture uncovers the political and ideological foundations of grammars of action. The CI 9s are not merely a grammar. They do not merely describe replicable inter-activities of humans and machines. They are put into place to make “discoverable” captive subjects in ways that are deeply grounded in a politics of exclusion and an ideology of racism.

Within these grammars of actions, there is persistence. Although, in the previous two chapters, I have read for instances of resistance in the slips and errors and potential deceptions riddled all through the system, I also want to recognize that resistance can take an even quieter form. Reading into the dates of arrival onf so many of these certificates, a new collective portrait emerges of practices of refusal and persistence. Here, the refusal to be forced out. Here, the persistence of those who endured hardship upon hardship. Unwittingly, the CI 9s capture this refusal and this persistence. Even though grammars of action were directed towards the capture of Chinese migrants for the purposes of exclusion founded on racist motivations, they are also a place to look for that which the system did not mean to show: the quiet dignity of people who endured and persisted.

The grammar of persistence leverages grammars of action. If the latter are intended, in the case of the CI 9s, to capture migrant bodies, the former exists within the cramped space of that capture in order to transform it. The photographs themselves, despite being the product of a repressive state demand, become a site for the grammar of persistence. In this other turn to grammar, the visual grammar of the migrant caught in the photographic frame, I am guided by Tina Campt’s reading of what she identifies as the “tense grammar” of people photographed for the purposes of their own subjugation. For Campt, the tension of stasis, the work of holding still and refusing to be moved, is a crucial part of the power of these images. In this, they share a capacity of refusal alongside the passport photographs of African Caribbean migrants to the United Kingdom, which, as Campt notes in an interview with Kevin Coleman, register “as a refusal to embrace the limitations of the category of containment produced by the genre of the passport photo itself” (Coleman 2018, 214). These photographs encompass “practices of refusal” (Campt 2017, 41). They refuse to be contained by the photographic genre of the identification photograph. They demand to be seen, and heard, in ways that far exceed and undermine their original function.

They demand to be seen and heard because, as Campt reminds us, there is no such thing as an absolutely silent photograph. Instead, there are quiet images. Quietness must not be mistaken for silence. It has, as Campt insists, a frequency. It hums. We have to listen for it. As Campt tells Coleman, quiet images are differently telling than “spectacular images or images that make grand statements.” She says that we must think “about how to attune our attention to the undercurrents of images.” Instead of “complete silence,” she “believe[s] there are quiet moments and that those quiet moments are dense and require us to unpack them in complex and nuanced ways” (Coleman 2018, 210). To hear the quiet of an image is to “engage the affective registers of the image,” and those registers allow us to “apprehend in these photos … the ways the individuals are challenging the government’s capacity to refuse their capacity to relocate at will. So, here again, we see them refusing the refusal of the state” (214). This practice of refusing refusal reverberates throughout the CI 9 photographic archive. In the faces of these thousands of migrants there is a refusal of the state’s refusal to count them out. They are captured, but they are not captive.

What is more, there is a complex beauty in these images of the mass captured. Describing her reaction to the ethnographic photographs of South African women who had been brought to the Eastern Cape to build farms, Campt writes: “I’m conflicted by the beauty I see in them, perplexed by the quiet introspection they so hauntingly depict. I see images of black women with dignity and stature … Yet viewed in their historical and institutional context, they witness a transliteration of beauty into racialized cultural categories and confront us with a vulnerability that also frames each of these women’s photographic presentations” (2017, 50). I have also experienced this tension in my work with the CI 9 photographs. For me, they are haunting not only because of the repression they depict, but also because I do see beauty, strength, and dignity in them. Campt resolves this tension between the beautiful and the repressive by turning to Darieck Scott’s work on “‘muscular tension’ for theorizing an alternate vision of black futurity and possibility”: Scott’s theorization shows how “muscular tension constitutes a state of black powerfulness in the midst of debility, a form of resistance expressed through a refusal to accept or acquiesce to defeat” (ibid.). Campt’s reading of refusal in the tense stillness in photographs made for the purposes of colonization and imperial expansion opens up a way to see the CI 9 photographs as engaging in similar practices. The practices of refusal in the CI 9s are not identical to those of the South African women in the Eastern Cape. I acknowledge the crucial differences between the experiences of Black subjection and slavery, and that of the Chinese migrants caught in the CI 9 archive. I also, as I discuss in chapter 1, seek out the possibility of intersections and affinities between Black slavery and Asian indenture, between Black subjection and the Chinese migrants captured in the CI 9 archive.

In the quiet of the CI 9 photographs, there is a tense grammar of stasis, not stillness. For Campt, stasis demands seeing beyond stillness, demands feeling:

Engaging in these portraits [of South African women] as stasis rather than stillness means that, rather than motionlessness, what we see is an effortful equilibrium achieved through a labored balancing of opposing forces and flows. These images require us to do more than just see stasis, for they capture unvisible forms of motion held in tense suspension. Their stasis registers beyond what we see, like the vibrations that form the fundamental basis of sonic frequency … Their stasis requires us to listen to the infrasonic frequencies of images that register through feeling rather than vision or audible sound. (Campt 2017, 52)

Campt’s analysis helps me to finally understand my own deeply affective relation to the CI 9 archives. I have been studying them for nearly a decade. It is hard for me to look at them for very long without weeping. What they hold at bay and what they make so visible is a legacy of decades of subjection to deep inequity and unmasked racism. Mrs Peter Chow enters our field of vision looking straight into the camera. Her eyes are clear and open wide. Her mouth held still, the corners only slightly turned downward. How much strength must it take to maintain so much impassivity in the face of the undisguised contempt and discrimination to which she, and every other Chinese migrant in this archive, had been subjected? Such stillness is a labour. It demands exertion. Unlike the triumphant photographs of the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where Chinese labour is clearly visible even if displaced by the spectacle of white men driving in the ceremonial last spike, the CI 9 photographs are images of deep exertion, and of labour that cannot be clearly seen. No one is holding a pick-axe in these images. Indeed, often these photographs are images of exertion’s opposite. They might seem, at first glance, to capture an instance of repose. But it would be a mistake to miss the energy put into repose – to mistake stasis for stillness. Mrs Peter Chow does not hold still. She must actively hold herself in. Refusing refusal can be quiet work, but it is still work. It is a labour that demands a tense grammar of every mass captured body.

There is a visual economy to the extractive labour demands of settler colonization. Such an economy might sometimes be spectacularly visible. For example, the photographic history of Chinese labour on display in images of railway gangs (see figs. 3.4 and 3.5 in chapter 3). There is no labour on display in the CI 9 photographs, but that does not mean that there is no work happening in these images. The refusal of spectacle, the quiet positioning of the self as contained against containment, is also part of the labour captured by photographic legacies of colonial expansion. As Adrian De Leon understands with respect to the intertwining of the visuality of labour and colonialism, small acts should not be overlooked; we must, instead, develop “reading practices that recognize small-scale negotiations around the camera” so that “we can observe emergent labor politics that take place within this visual economy” (2018, 77). De Leon writes about colonial photography in the Philippines and how it works to “separate culture from economy and thus deny the political economy of Cordillerans and sovereignty claims to their land” (ibid.). Although the CI 9 photographs function very differently, in that they are made to track the movements of Chinese migrants rather than the extraction of their labour, they share an affinity with the colonial photography of De Leon’s study: they are a visual record of the intersection of racialized labour and photography taken as a key element of the scaffold of settler colonization.

The persistent grammar of the CI 9 photographs is a visual grammar that works against mass capture’s sociotechnical grammar of action. Agre’s grammars of actions show us how human-machine interactions are codified as units of replicability so that, in the case of CI 9s, information can be captured for the purposes of producing non-citizen subjects. Campt’s tense grammar illuminates the tremendous labour that is at the core of how we can understand De Leon’s “small-scale negotiations” that are part of the practices of refusal in colonial photography. These two grammars are different but connected. One is a grammar of capture, the other of resistance. In the final part of this chapter, I want to examine one more iteration of grammar and persistence in the CI 9s: the language on the actual certificates.

Persistent Tension

While the previous section uses Campt’s idea of tense grammar to track the positioning of bodies in and against the frame of colonial photography, I now want to follow another form of tension on the CI 9s constituted by the grammar of the certificate itself. There is a persistent tension in every CI 9: the language demands forms of self-declaration or confession that are simultaneously working to flatten or, in some cases, completely erase the identity of the self-declaring subject. On each certificate, there is a series of self-declarations that deny selfhood. The language of the certificate is written in the first person, but the person making these declarations is only one out of at least three people actually authoring the form. In order to fill in the blanks of each certificate, there must be in place the Chinese migrant who provides the information, the customs agent who enters the information, and the interpreter who tells the agent what to write. Should the migrant return to Canada, then there would be the additional entries of the agent at the port of re-entry and, again, the interpreter providing the actual evidence necessary for permitting re-entry. Even in the case of those migrants such as Mrs Peter Chow who apparently did not return to Canada, there is a persistent tension in the grammar of the certificate itself. This tension resides in a contradiction of authorship. What Mrs Chow says of herself is not necessarily what is recorded on the certificate. And even if the information on the certificate perfectly corresponds with what Mrs Chow gives as the details of her life, there remains the tension of a migrant declaring oneself to be something in the first person but doing so at a doubled remove, through the intermediating hand of the agent and the interpreter.

Look again at Mrs Peter Chow’s CI 9 (fig. 4.2). Transcribing the text of the certificate, her identification details would read as follows:

To the Collector of Customs, Port of Victoria, B.C.

I hereby give notice that I desire to leave Canada with the intention of returning thereto. I propose to sail or depart from the Port of Victoria, B.C. for Hong Kong on the [blank] day of Oct 5 1910. I intend to return to Canada at the port of [blank].

I request registration and I attach thereby my photograph hereto and give the following information for the purpose of my identification on my return.

My proper name is Mrs. Peter Chow

I am sometimes known as [blank]

I first came to Canada in the year 1889

Certificate of Registration From C.I. 5, No. Lost

My place of residence is Victoria

Where I have resided since 1889

My present occupation is that of Merchant’s Cook’s Wife

My place of birth was Foot-Ning

My present age is 28

Height 4 feet 9 inches

Facial marks or other peculiarities: —

Small mole back of neck

Very light pit on left cheek

light scar on right cheek

I am personally known to Ma Chau and Ma Art both of Victoria, B.C. to whom I would refer you to for corrections for statements herein made.

Mrs. Peter Chow

(Signature of Chinese Person.)

In this transcription, I have italicized all the words on the certificate that were filled into the pre-existing blanks, but italicization does not, of course, give you a sense of the range of hands at work in completing each blank. First, there are the handwritten and typographic scripts. “Victoria, B.C.” and the date, “Oct 5 1910,” are clearly inserted through a pre-set stamp.

Who authors these entries? Whose handwriting is on these certificates? The answers are in the secretary of state’s annual Civil Service List – a compendium of the name of every person, from chief controller to janitor, employed by the federal civil service, along with the date of their appointment, their date of birth, and their annual salary. The CI 9 entries were authored by agents who were officially called examining officers by the Department of Customs. Because the vast majority of migrants entered and exited Canada from either Victoria or Vancouver, the examining officers at those two branches would have been the ones largely responsible for nearly every entry in the CI 9 archive. The Civil Service List does note the employment of a Chinese interpreter in Montreal as well as in Vancouver and Victoria, but the number of certificates generated out of central and eastern Canada does not compare with those created and filed in British Columbia. Note that the examining officers who sign off on each certificate are employed by a different department of the federal government (Customs) than the one actually responsible for Chinese immigration (the Department of Trade and Commerce). The Civil Service List for 1910, the year of Mrs Peter Chow’s CI 9, clearly identifies the collector of customs, to whom the CI 9 is addressed in the first instance, and the interpreter, who is all but invisible on the form, as employed by the Chinese Immigration branch of the Department of Trade and Commerce (Sessional 1910, 54). That same list classifies all the examining officers under the Department of Customs (129–31). I am belabouring the fact that the certificate’s institutional address is different from that of its authorship because it is another form of tension in the certificate. One department is the addressee and archival home of the certificate. An entirely different department enters the information captured on it.

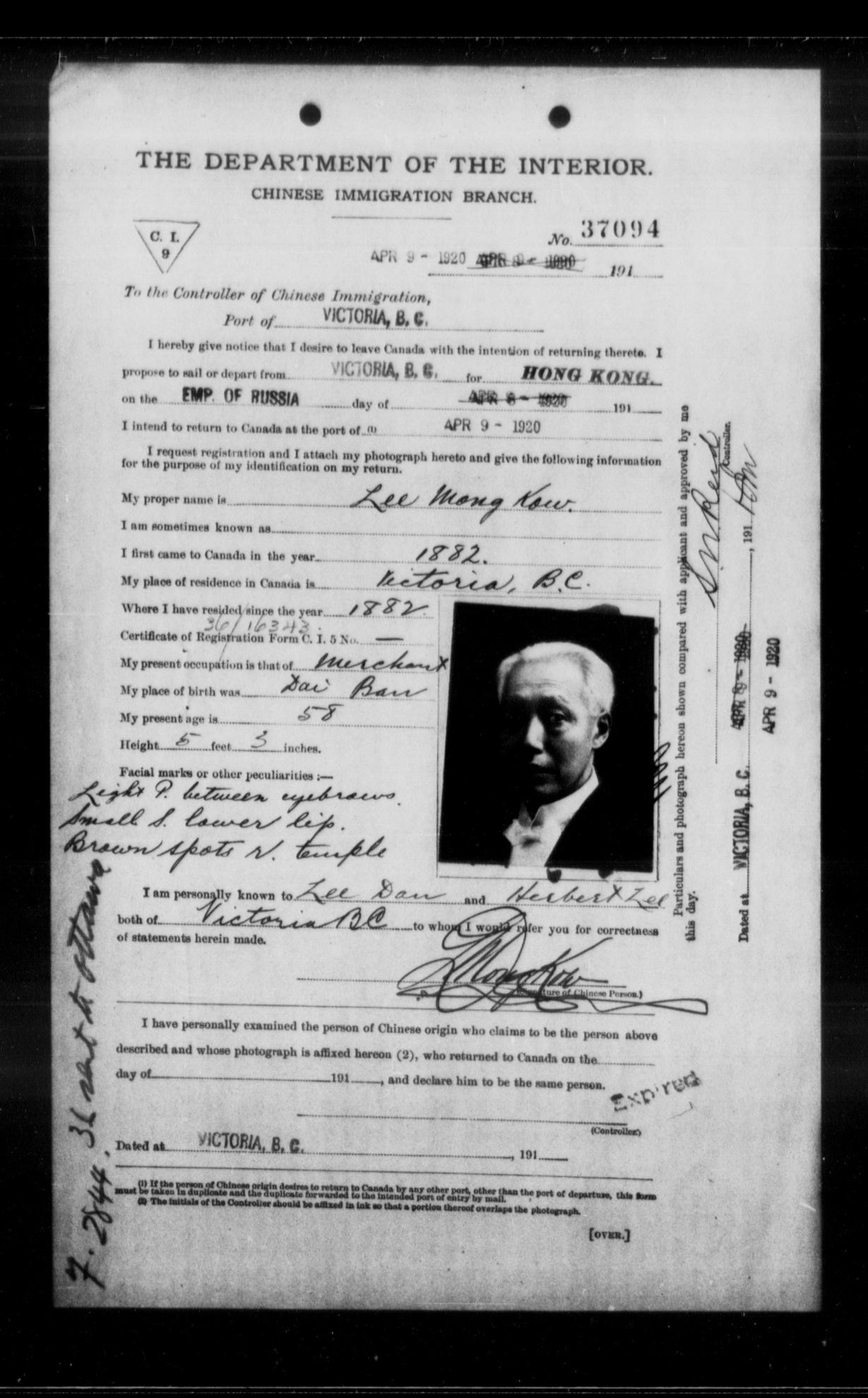

The text that is filled in on each CI 9 is a complex form of collaborative authorship involving the migrant, an interpreter, and the examining officer. The latter’s hand is the most visible on the certificate. For example, next to Mrs Peter Chow’s photograph is the signature of the examining officer, Samuel Wesley Edwards. According the 1910 Sessional Papers of the Dominion of Canada (which publishes the secretary of state’s Civil Service List), Edwards was born in 1858, which meant that he was fifty-two years old when he would have signed off on Mrs Peter Chow’s identification photograph. He had been appointed to the position since 1904 and earned $950 per annum in this role (Sessional 1910, 130). Edwards would have been aided in his work by Lee Mong Kow, the sole interpreter employed at the Victoria office of the Department of Trade and Commerce. Lee had held this position since November 1889. He was forty-nine years old when he would have interpreted Mrs Chow’s answers for Edwards. He was younger than Edwards but earned significantly more money, $1,200 per year (54). Given the racism of this time, it may be surprising that a Chinese person could earn more than his white colleagues, but it is important to remember that the interpreter positions, unlike all of the other staff positions in this office, were political appointments. From my study of all the salaries in the Civil Service List for 1910, it becomes clear that the examining officer is one of the most poorly paid positions. The only people who earned less were a handful of “preventative officers” who were paid $650 a year for their work. The men who were charged with the responsibility of examining and verifying the identity and information for the Chinese migrants captured on each CI 9s were themselves some of the least valued members of the federal civil service.

Remuneration aside, and returning to the question of authorship, the information recorded on the CI 9s can thus be said to have three “authors”: the examining officer, the Chinese interpreter, and the Chinese migrant. In this scene of tripled authorship, the role of the interpreter is key. As Lisa Mar argues, “enforcement of the head tax depended on Chinese collaborators, which deeply affected its character. Interpreters handled most communications between arriving immigrants and Anglo officials” (2010, 23). Given the important role of interpreters for the construction of the CI 9s, and their invisibility on the forms themselves, I want to offer a brief portrait of the curious position that interpreters held and then look more closely at the man who would have interpreted the answers given on the CI 9s I have discussed in this chapter.

The interpreters held considerable power over the fates of Chinese migrants. Aside from the interpreters, none of the officials that a Chinese migrant would deal with would have spoken any Chinese. The vast majority of migrants spoke little to no English. Such a situation rendered the Chinese interpreters both potential advocates for migrants and collaborators with the state. These positions were political appointments and they were often held by a single person in a given office for many years. Given the power accorded to interpreters, corruption or abuse of the position is inevitable. Mar gives the example of Yip On, who served for decades as the interpreter for the Vancouver branch of the Department of Trade and Commerce. In 1908, Mar reports that a Chinese merchant named Lum Ching, who had resided in British Columbia for twenty-nine years, attempted to re-enter Canada after a visit to China. “Yip On denied all evidence of Lum’s merchant status and naturalized citizenship [something that was available to merchants]. Yip On detained Lum until he paid the $500 head tax as if he were a newly arrived Chinese laborer” (2010, 24–5). Mar notes that it was harder to re-enter Canada than to enter for the first time, and, “like Lum, a great many Chinese returning from visits to China struggled to prove their identities” (25). Interpreters worked within a nexus of power and interest from Canadian political parties, corporations, Chinese communities, and trade networks in Hong Kong and China.

The man who interpreted Mrs Peter Chow’s answers to Examining Officer Edwards was Lee Mong Kow. He was the sole interpreter for the Victoria branch of the Department of Trade and Commerce for thirty-one years. He was a prominent member of the Chinese-Canadian community and was also highly regarded in the Anglo-European community. Under the title “A Remarkable Canadian Chinaman,” the 1 May 1909 issue of MacLean’s published a photograph of Lee Mong Kow alongside a flattering profile written by R.B. Bennett (who would eventually become Conservative prime minister from 1930 to 1935) (fig. 4.4).

Lee is on the right, pictured with his mother, his wife, and their five children. Unlike the fractured portrait of the Lawsons that I assembled in chapter 3, here is a family portrait that follows the conventions of most normative family photography. All the members of the family are together in a single frame. Their relative importance is signalled by their position in the photograph. In this case, Lee’s mother, the matriarch, is at the centre of the frame. She holds in her lap the youngest member of the family so that the image is anchored by the force of familial history and the promise of its future. Lee Mong Kow and his wife Seto Chang Ann flank the family. More than the opulence of their clothing, the photograph reinforces the Lee family’s stature by the simple fact that the whole family can be depicted together. This photograph was published one year before he would take down the particulars of Mrs Peter Chow’s identity for her CI 9. Bennett’s article commends Lee’s service to the crown: “As might be expected, he makes enemies of his countrymen and it is not uncommon for those who are interested in the immigration of coolie labor and who have been frustrated in their designs by the wit of the Chinese interpreter to charge wrongdoing on his part. But, after 10 years of service, it has not yet been shown that he ever acted dishonestly and Lee Mong Kow commands wide respect” (1909, 67). After covering some of Lee’s biographical information (his past as the son of a merchant, a house that he bought in the fashionable Victoria neighbourhood called “the Gorge”), Bennett closes the profile by asserting that Lee is the ideal type of Chinese immigrant, not least because he has assimilated so well. “While conservative, Lee Mong Kow is only natural, for few of us change from the style and customs to which we have been accustomed, and after all he comes nearer to being a ‘white’ man than many a Caucasian. If all Oriental immigrants were such as he, the ‘yellow peril’ would not be the problem that it is feared in America” (67). Contrary to Lee’s representation in the popular press, Mar observes that his record is not entirely immaculate. There was evidence of his misconduct in a habeas corpus case relating to an alleged prostitute in 1901 (2010, 143n17), and business records that show he ran an illegal gambling den (2010, 62). Lee held tremendous power not least because of the length of his tenure in the busiest port of departure for Chinese migrants in Canada. It is no exaggeration to say that he controlled the fates of thousands of Chinese migrants.

Given the discrepancy of power between Mrs Peter Chow and Lee Mong Kow, it is hard to imagine that her encounter with him would have been without tension. Like every Chinese migrant who appeared before him, she needed something from him, which he could choose not to provide. Edwards, as the examining officer, may have written the information on the certificate and signed his name to it, but Lee told him what to write. Lee’s power is especially insidious in that his hand is nowhere visible on the certificate. Edwards signs. Mrs Peter Chow signs. But not Lee Mong Kow. His name is not on this certificate. It is not on any of them other than his own.

The CI 9 in figure 4.5 records Lee’s permanent departure from Canada. He had finally left his position as an interpreter and, according to his entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, he took up a position as the Chinese agent for the Canadian Pacific Ocean Services Limited (Stanley 1921–30). Prior to CI 9 no. 37094, Lee Mong Kow’s name is invisible in the CI 9 archive even though his words are recorded on tens of thousands of certificates. It is only on CI 9 no. 37094 that we can see, via his signature, his handwriting, or at least what we are told is his handwriting, for the first and last time. Lee’s CI 9 might be the one that is most free of the tension that riddles the others. He was a man for whom the tensions of the invisible authorial relationship between interpreter, migrant, and examining officer had been radically reduced. Not for him the uncertainty of wondering if the interpreter would faithfully and favourably transmit the information provided by the migrant. Unlike Mrs Peter Chow, Lee was a true collaborator in the text of his certificate.

As the handwriting on the certificates makes clear, even in the case of Lee Mong Kow it is not the subject of the certificate who inscribes its content. The inscription is done by proxy on his behalf. Despite the immediacy of the language of the first-person voice on each certificate, the CI 9 is a document of persistent tensions in the discrepancy between the grammar of its declarations and the practices by which those declarations are made. Mass capture on the CI 9 demands that the migrant answer a series of questions about their identity. Each answer is translated and written down (or, in later years, typed). Almost every certificate involves two proxies, the interpreter and examining officer. The language of the certificate attempts to obscure these two proxies, these two removes from the subject of the certificate itself. What is more, the language of the certificate is relentlessly personal in its insistence on the first-person pronoun: my name is; my occupation is; I came to Canada in; I am personally known to. This tension between the first-person declaratives and the third-person interferences literally written all over the form itself persists.

It is no accident that diplomatics shares an etymological root with diplomacy. Diplomatics, the study of documents and the processes of establishing their authenticity, comes to matter when people and documents start to move around more. Diplomacy, as Duranti notes, comes from the French word “diplomatie [and] refers to the art of conducting international negotiations which result in the compilation and exchange of documents, namely diplomas” (1989, 12). The increasing need for documents to speak for others through processes of cross-border exchange sheds a different light on the CI 9 as a type of diplomatic process. Indeed, as I will show in the next chapter, the CI 9 resembles a passport insofar as it guarantees the bearer’s right to return to the country of issuance. A passport tells the agent that the bearer has the right to return to the nation from which the passport originates. A passport does not guarantee the bearer the right to leave a country; it guarantees the right to return. Of course, in the case of the CI 9, the bearer is being guaranteed the right to return to a nation-state that insists on excluding them. In the next chapter I will think through the contradiction of treating Chinese migrants as though they were citizens only for the purposes of re-entry. As I will show, the CI 9s anticipate the demands of the contemporary passport.

On a passport, the bearer does not speak. The document speaks on behalf of the head of the nation-state which issued it, to the person (usually a border agent or official) the passport is presented to. The bearer has no role, no voice, in that conversation. In contrast, on the CI 9, the bearer is compelled to speak by virtue of the language of the form. That speaking, as this chapter shows, is rife with tension. Despite the repressive functions of this document, and the ways in which it nakedly attempts to make a racial other knowable through grammars of action that constitute mass capture, there are a host of alternate and tense grammars that actively refuse captivity. In the identification photographs that refuse to be contained by their genre, in the tension of the authorship of each CI 9, there is what Campt knows is stasis and not stillness. Hold still, these certificates demand. Holding still, the subjects of these certificates reveal the resilience of their refusal. In listening to the image of the identification photographs on each CI 9, we can come closer to hearing the long history of the refusal to be refused.