8 Designing and Assessing Aims, Goals, Objectives (AGO)

“The continual dialogue and reflection on aims [should come] at a time when economics, advancement in social status, and standardized testing seem to be the purpose of schooling.” — Noddings 2003

Introduction

The benchmarks for teaching and learning are often expressed in the form of a scope (breadth of learning) and sequence (order of learning skills) to be addressed in a particular content area, beginning with aims, moving to goals, and then objectives. Aims, goals, and objectives are thought of as hierarchically ordered educational purposes (Noddings, 2008).

Essential Questions

- Why are curriculum coordination and articulation critical elements in the curriculum design process?

- How are aims, goals, and objectives (AGO) defined?

- How can AGO be used in curriculum planning?

- What are the advantages of behavioral objectives?

- What are the strengths of Madeline Hunter’s Lesson Plan Model? What are the drawbacks?

Curriculum Coordination and Articulation

Before Aims, Goals and Objectives can be developed, it is essential that there is a plan for what the curriculum focus will be at a given grade level, and from grade level to grade level.

Curriculum Coordination

Curriculum coordination is the extent of the focus and horizontal connectivity at a given level (or in a course) for a school or district. An example would be five teachers who teach math. For curriculum coordination to happen, the five teachers do not have to teach the same thing at the same time, but the content and scope of what is to be taught should be the same. Teachers should be given the freedom to adapt to the differences in learners, such as using appropriate strategies to meet the students’ needs (English, 2000).

Curriculum Articulation

Curriculum articulation describes the focus and vertical connectivity in a school or school system. It describes the sequence of learning for students. For articulation to occur, curriculum designers and teachers must know what the curriculum was in the grade below and the grade above. What students know and expected to do in third grade should flow smoothly into what they need to know and be able to do in fourth grade so that they have the knowledge and skills to be successful in fifth grade. For articulation to be successful, the curriculum must be connected vertically, K-12, from elementary school to middle school through high school.

It often happens that coordination can occur at one level, but articulation is lost at the next grade level if there is not communication about the curriculum content and focus at each level.

In my experience as a coordinator of curriculum and instruction, this was a major problem with site-based management. When an individual school was in charge of developing their own curriculum, there were often duplications in content. I observed this at an elementary school where units on the rain forest were taught at every grade level. Major gaps also occurred, as in a middle school where world history/ the eastern hemisphere was not taught at all because the teachers had developed favorite units on the Civil War. This is very problematic for the next levels because students may not have the background knowledge required for the next levels of learning.

One successful plan for developing curriculum coordination and articulation is to create articulation teams; that is teachers at the different grade levels who agree on what should be taught at each level. This can also be guided in part by academic standards.

After the articulation teams have completed their work, coordination teams consisting of teachers at the same level, or those teaching the same courses, decide what content will be taught across the grade level or courses. Their work is foundational for the Aims, Goals and Objectives that follow.

Articulation and Coordination of Curriculum

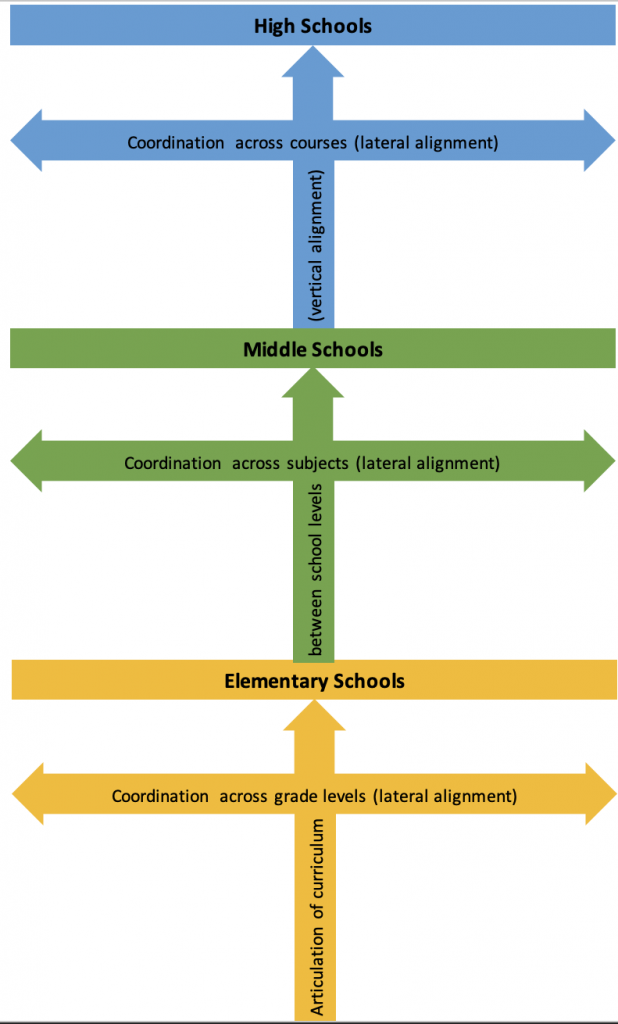

The following flowchart is a visual representation of how curriculum is articulated between school levels and coordinated across grades, subjects, and courses.

Downloadable version: Chap 8 School System Unit Analysis Graph

Defining Aims, Goals, and Objectives (AGO)

In describing the differences between aims, goals, and objectives, Leslie Owen Wilson in The Second Principle states that:

AGO is not only an easy acronym, it is an easy way to remember the correct progression from larger ideas to smaller instructional components. In everyday English we tend to use these terms interchangeably. Within the educational lexicon of curriculum development, for the past three decades scores of curriculum scholars, planners, and administrators have been trying to standardize terms so that they refer to very specific curricular components. The following definitions are broadly accepted by groups trying to standardize terms for writing curriculum. They are also attempting to standardize these terms so that they are not confusing to readers and users. (It might be helpful to remember the acronym AGO in order to get the sequence straight.)

Aims

Aims provide the general direction of learning and are written in broad terms that encompass more than one grade level. Standards are often used as aims. For example, The Colorado Academic Standards (CAS) are the expectations of what students need to know and be able to do at the end of each grade. They also stand as the values and content organizers of what Colorado sees as the future skills and essential knowledge for our next generation to be more successful. State standards are the basis of the annual state assessment. An example of an aim for students in all grades is “Apply standard English conventions to effectively communicate with written language.”

Goals

Goal statements are more specific than aims, and they describe learning expectations for students. An example of goal for sixth-grade writers is “Edit for grammar, usage, correct spelling and clarity to give writing its precision and legitimacy.”

Objectives

Objectives are specific, measurable competencies that are assessed to determine whether the goal (or part of a goal) had been met. An example of a specific lesson objective is “The student will write an essay on ‘My Favorite Pet’ with no spelling errors.” Please note that the entire goal is not met as a result of this objective, but rather a part of the goal.

Clarifying AGOs

Some confusion has arisen in the U.S. because the three terms have been collapsed into “standards.” Noddings stresses that the terms are not as important as the underlying structure and how they are related. There have been instances in curriculum development where aims and goals have been eliminated in favor of objectives, which are measurable. This is a mistake because the “vagueness” of aims and goals statements can be useful because it invites “aims talk.”

These “talks” can be very productive because they require curriculum developers, teachers, administrators, and the community to determine whether or not the broad learnings described by the aims reflect the values of the schools and community as well as alignment with the local or state standards. For instance, if an aim of the curriculum is to prepare students to be literate members of a democratic society, this is very broad, and must be “filled out” as goals (Noddings, 2007). It might follow that a fifth-grade goal would be for students to learn about American history with a goal of “understanding the importance of the Declaration of Independence.”

The next step after establishing goals is to construct objectives to define what “understanding” means. This translates into measurable student objectives, such as, “Describe how the Declaration of Independence lead to the Revolutionary War.” In teaching to this objective, the role of the teacher is to keep the goal and aim in mind and then provide meaningful learning activities to help students meet the objective.

The challenge with the terms aims, goals, and objectives is that there is little consensus on what they mean, except that they all have to do with what students should know and be able to do (Marzano, 2013). For further explanation, details, and examples of AGOs, refer to the Curriculum Development: Aims, Goals and objective purpose in curriculum development Slideshare.

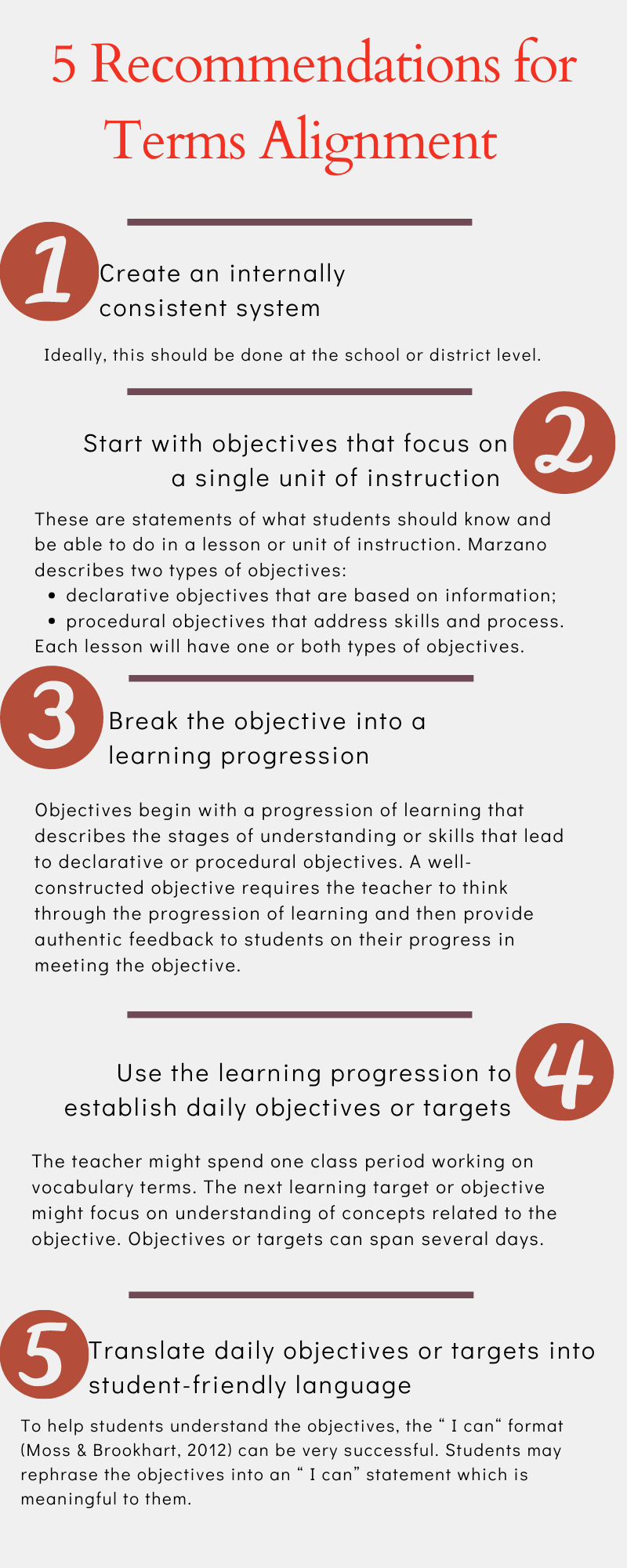

Marzano offers five recommendations to help educators evaluate how their terms align:

Downloadable version: Five Recommendations for Terms Alignment

There is an art to writing good curriculum and clear objectives. Wilson (2020) states that objectives are used in most lessons, and they generally describe the process of writing curriculum using behavioral objectives so that the teacher will know whether or not learning has occurred. She is quick to point out that there are other types of objectives, such as those in problem-based learning. Some advantages of behavioral objectives, according to Wilson, are that they are easy to write, and to generally easy to evaluate.

Writing Good Curriculum That Is Teacher Friendly

In addition to the having appropriate aims, goals and objectives, it is important that the end product is teacher friendly and something they want to use. Wilson does an excellent job of describing this in Writing Good Curriculum on The Second Principle.

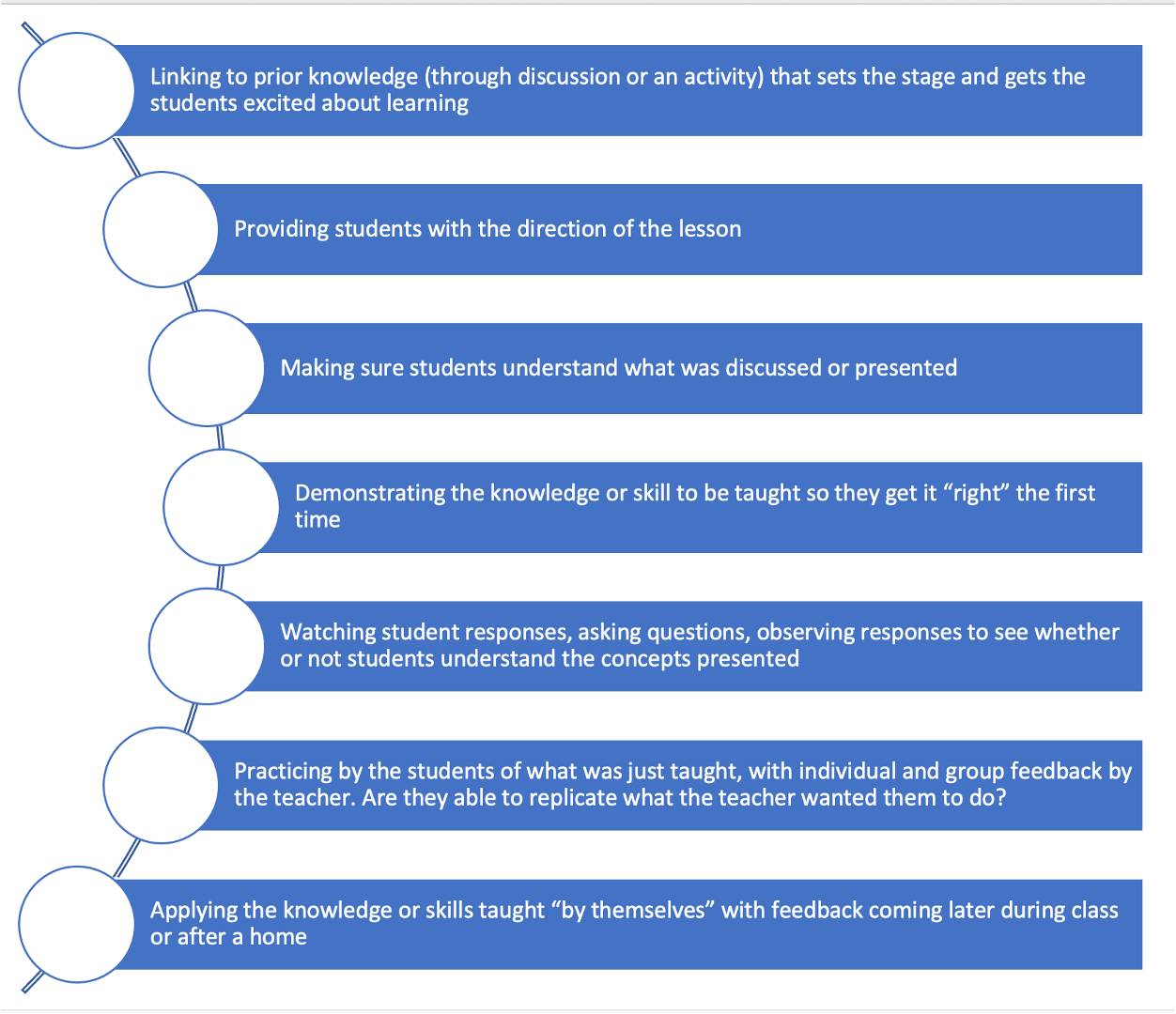

Madeline Hunter, who was an early advocate of objectives, is well known for her lesson plan model that is very structured. My personal experience with Madeline was when she came to our district and offered this analogy: “Is it better to have a lesson that uses a ‘shotgun’ approach which is lacking a logical sequence that may be haphazard in terms of planning and teaching, or a ‘string of pearls’” which has a logical sequence to the lesson and is planned and explicit? This was an excellent question at a time when site-based management was very popular, and teachers often relied on spur-of-the-moment lessons that were of questionable quality. Hunter’s “String of Pearls” approach is as follows:

Downloadable version: Madeline Hunter’s String of Pearls.

Closure was always my favorite part of the lesson, because I could find out what the students learned, or in some cases, thought they had learned. I also found that students retained the concepts longer if they were able to reiterate what they learned.

One of the reasons Hunter’s Lesson Plan became so popular was because it offered a road map for learning at a time when teachers did not always have a direction. Her “Direct Instruction” model was welcomed by administrators because they could provide guidance to new teachers. All these things were well and good, but in many cases, the model was used in a rigid way that I believe Hunter never intended. Hunter was open to adapting lessons and leaving out steps if that was appropriate for the students. As a university instructor, I have often used the Hunter Lesson Plan Model when teaching undergraduate literacy courses and in supervising student teachers. However, it is not the only teaching model, and it is not an appropriate plan for problem-based learning or learning scenarios that require more creative thinking. Not all lessons can be described in behavioral objectives, particularly those that are based on problem-solving or constructivist in nature. It is, however, a good starting point, but it should be only one of many teaching models in a master teacher’s toolbox.

Insight 8

The inclusion aims, goals, and objectives are an important part of curriculum development, but the process should open to including lessons that encourage problem-solving and inquiry that do not require pre-written objectives, but are still specific in terms of the larger learning goals.

Interactive Learning Activity (ILA) 8.1

Download and then use the following Venn diagram to compare Leslie Owen Wilson’s approach to writing curriculum with Hunter’s lesson plan. Which areas overlap? Which areas are unique to the individual approaches? Respond with your findings using the ILA Responses group in the Hypothesis annotation tool.

Summary

In curriculum planning, aims, goals and objectives are tools used in curriculum development because they provide a hierarchical system for all grade levels/subjects with aims, then goals for specific subjects/grade levels or units, and finally objectives for individual lessons. The Hunter Model is useful for curriculum planning, but it has limits in terms of defining learning in behavioral terms. The next chapter will explore how educators can plan for lessons that encourage problem solving and creative thinking.

Additional Information

The following resources may be helpful in writing teacher-friendly curriculum and designing aims, goals, and objectives:

- Curriculum Studies, Appendix: II—pp. 116-117

- The Second Principle, Writing Curriculum: Aims, Goals and Objectives

- Designing and Assessing Educational Objectives