15 Curriculum, Technology, and Teaching in Challenging Times

“In a world where knowledge and information are abundant and so easily accessible, the roles of teachers and learners are transformed and blended. The walls of the classroom have been extended through new technologies and in this extended classroom roles must adapt.” –Grace Nyagah

Introduction

Technology has had a tremendous impact on the curriculum, particularly in the year when the pandemic struck, and nearly all schools went “online.”

Many teachers had a “crash course” in using technology, with mixed results. In the long term, the most effective use of technology requires thoughtful changes in how to teach. It is a combined effect of best teaching practices and sound technologies that lead to improvements in learning. Teachers have to discover in what ways technology is a tool that supports particular teaching or learning strategies that benefit their students.

Essential Questions

- How has teaching changed as a result of technology and the avalanche of new information?

- Why is digital citizenship an important dimension in online teaching?

- How might teachers stay in the classroom and also be involved in curriculum development?

- Why has the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation moved away from funding teacher performance initiatives to curriculum?

- What is needed to properly integrate educational technology in support of students academically?

A Journey with Technology

When my parents got married in 1929, my father had just graduated from college with a degree in chemical engineering, my mother had just finished her freshman year studying dietetics. The stock market crash that August dashed their career plans, and they were glad to get teaching jobs in a small community on the Dolores River in western Colorado. My mother was just 19 years old, but her one year of college was enough to get a teaching certificate.

The most “high tech” invention in their lives, outside of their prized Model A car, was the camera that took their picture. In Gateway, Colorado, they taught the students in grades one through twelve in a two-room school. Daddy taught all the high schoolers and Mother taught the younger students, and between them, they taught all the subjects.

My husband and I followed in my parents’ footsteps when we got our first teaching jobs, also on Colorado’s western slope. In my first-grade classroom in Montrose, I had access to a record player (for teaching music), a film strip projector for showing slide shows, and a mimeograph machine to duplicate work pages for the students. On special occasions, the first-grade teachers would get the classes together in a large room and show a 20-minute science movie or cartoon to the students using a 16-millimeter projector and a screen. It was a highlight for the kids because many did not own television sets or get to go to the movies.

A tech “glitch” sometimes arose when the film got stuck in the projector, and we teachers would watch in horror as the film frames literally burned up inside the projector. A speedy fix was to have a pair of scissors and cellophane tape. The burned frames were quickly cut from the rest of the film with scissors, and then rest of the film was spliced together using the tape. If the film” fix” was not speedy, chaos would reign as the 90 first graders squirmed, talked and laughed, so it behooved the teacher doing the fixing to make sure the film was threaded correctly and that the small fire was extinguished as fast as possible! Fortunately, the principal at our school was also the audio-visual coordinator (an early tech position?) who would later remove the tape and reattach the film correctly. I recall his office being filled with broken projectors, films, and other devices.

Fast forward to my next teaching position in the 1980s at a middle school in northern Colorado. I was a special education teacher and shared a room with a tech-whiz, Barbara, who brought a personal computer to our classroom. I had seen computers before, but only the large mainframes like the one that made use of computer cards. I had typed my husband’s dissertation on a Royal electric typewriter (also “high tech” at that time). By the time I completed my study, I hired a friend who had purchased a very large, but state-of-the-art computer (higher tech) for $10,000, a whopping amount in 1980. It did a great job and it was the foundation of her dissertation typing business.

Back to Barbara, a behavior interventionist, and the early Apple computer in the classroom. I watched Barbara write documents, print reward coupons for her students and other teaching related things, but I did not ask about it because, in all honesty, it just intimidated me! One day, Barbara, having noticed my trepidation as I passed the computer, said, “Linda, sit down; I’m going to show you how to use the computer.”

I did not want to do it, but Barbara, being the expert that she was with reluctant and non-compliant students, won the contest. She showed me where the CPU (central processing unit) was, how to use the keyboard, and how to “boot” the computer using Apple Basic computer language, and how to do word processing with an early program called Peachy Writer that was difficult to use because you had to use symbols like underlining to show that a particular letter needed to be capitalized. I will be forever grateful to Barbara for ushering me into the computer age so that I could master the Apple 2E, and later the “Blueberry” I used later at the university, down to the iMac that I am using today. As I look at the iMac, I wonder where the central processing unit is, or if computers still have them.

I don’t mull over that thought very long; I am grateful that I teach at a time when schools may be shut down because of a pandemic, but my students are able to learn at home because they have computers and the internet. It is not a perfect system, but they are learning!

Insight 15.1

Technology has made gigantic strides in my generation and the generation of my parents. I can honestly say that “high tech” has made life both easier and harder. It is easier because we have the internet and knowledge at our fingertips, and we have dynamic tools for sharing information and ideas with students who are close by, as well as in places around the world. It is harder because the internet has both wonderful and terrible sites that can be accessed easily. In my college classroom, I am aware that students may be looking right at me but not comprehending what is being discussed because they are texting back and forth to friends on their phones. But the challenge is the same as what my parents faced years ago and what I and all teachers face today: engaging the students so they want to learn.

Digital Citizenship

With the use of technology as a part of the curriculum, some responsibilities fall on both teachers and students in the form of digital citizenship. Digital citizenship emphasizes a collaborative, creative, and self-empowering use of technology in education (Dotter, Hedges, & Parker, 2016) as well as in personal use. Definitions for digital citizenship can also include online behavior, norms, and responsible technology use. It reflects our goal to help students, as well as ourselves, develop the skills and perspectives necessary to live a digital lifestyle that is safe, ethical, and responsible, as well as inspired, innovative, and involved (Impero Software & Digital Citizenship Institute, 2016, p. 2).

Digital citizenship is neither a trend in technology development nor a label for online-behavior guidelines but instead is a matter of real issues impacting technology users regardless of age or status (Snyder, 2016). Because Web 2.0 (and potentially later versions) was developed with adults in mind, many interactions that occur online require a maturity level that many K–12 students, especially elementary-aged, may not be ready to manage. The maturity level necessary to engage with Web 2.0(+) tools is forcing students to mature faster than those in previous generations (Ribble & Miller, 2013).

For more about Web versions; features; and differences, refer to the article Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web 3.0 with their difference.

Essentials to Teach Students Digital Responsibility

When formulating a curriculum on digital citizenship, there are certain basics to touch upon including privacy protection, oversharing, cyberbullying, digital footprints and rules, netiquette, and source credibility.

Privacy Protection

This involves the use of strong passwords and the avoidance of interaction with strangers online.

Oversharing

Younger people are naturally more vulnerable and prone to self-revealing and oversharing online. A good course on digital citizenship should teach them what information is appropriate to share online and with whom.

Cyberbullying

As a growing phenomenon in schools, this new form of bullying can best be combatted by teaching our students how to effectively deal with it.

Positive Footprints in The Digital Age

From Sophia Anderson’s The Essentials to Teach Students Responsibilities.

With the explosion of social media, it is important to teach our students the importance of crafting a positive online persona and show them how to do it through our digital citizenship programs:

- Respectful communication online and voicing of one’s own opinion.

- Netiquette is an important part of being a digital citizen and should be taught to our students from a young age.

- Evaluating online information/website credibility.

- Digital citizenship literacy enables digital citizens to correctly curate informational content they find online and correctly evaluate the credibility of the websites from which they obtain their information.

- Copyright and plagiarism issues.

- This involves teaching our students not to take the work of others and pass it off as their own.

- Showing them how to credit their sources will teach them to better uphold digital ethics by respecting the original work of others.

- Consequences of non-abiding by digital rules.

With the growth of legislation on digital crimes, our students should be taught where the line is on many issues involving digital conduct so that they can intimately understand the consequences of breaking these digital rules.

To address these issues, it is important to follow guidelines for these practices that maximize learning for students, so they have the skills and abilities to learn using technology. The following section touches upon the technology standards designed for that purpose.

Technology Standards

The ISTE Standards (International Standards for Technology in Education) are designed for students, educators, and administrators. They may be used to shape how technology is integrated and utilized in the teaching and learning process. The standards are aligned so administrators, educators, and students may put forth an orchestrated effort to effectively implement technology within educational settings. Through this coordination, curriculum development, professional development, and student development through the use of technology support that includes blogs, ePortfolios, WebQuests, Wikis, digital storytelling. All of these support academic skills and may be used by collaborative groups to motivate and encourage discussions and critical-thinking skills.

Collaborating to Expand Technology Education

As the focus on educational technology (ed-tech) becomes a more prominent part of curriculum, so does what teachers need to do to effectively teach it. In this interview with Bill Gates, Lyon Terry, Teacher of the Year 2015, speaks to the strategies for meeting this demand.

With this shift in how teachers teach, all educators continually face the challenges of keeping up with technology, becoming skilled in the use and implementation of the latest technology trends, and creating learning strategies to properly equip students. These challenges increase the need for more knowledge, training, and funding of educational technology. Fortunately, educational foundations, organizations, and institutions as well as tech-savvy students offer ways in which these challenges may be overcome.

Educational Foundations/Organizations/Institutions as Ed Tech Partners

Great efforts are being made by educational foundations, organizations, and institutions to offer initiatives, programs, training, and up-to-date resources that enable teachers to “keep up” with the ever-changing technology and educational trends that come with it. For example, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation recently put forth plans to invest in professional development of providers who will train teachers on “high quality” curricula. Additionally, the Foundation is funding K-12 education from 2017-2022 for continued progress “in improving educational outcomes, the development of new curricula, charter schools focused on students with special needs, and ‘research and development’ for scalable models that could inform best practices” (Vara-Orta, 2017, October 19). For more information about specific funding efforts, refer to the “Gates Giving Millions to Train Teachers on ‘High Quality’ Curricula.”

Though funding such large efforts is a significant part of meeting ed-tech needs, other educational organizations offer additional support to educators. Many provide information about ed-tech innovations and trends through newsletters as well as free versions of different educational applications and examples of how others are implementing and using them. For example, Trendline is a newsletter focused on innovations in ed tech and OER Commons is an extensive resource for finding subject- or topic-specific curriculum and collaborative resource groups. There are many resources available to educators; it is just a matter of finding what works best for individual teacher and student needs.

Students as Ed Tech Teachers

Because technology changes so rapidly and skill levels vary among and between generations, peer groups, and especially teachers and students, a perfect opportunity for teachers to learn from their students presents itself in the form of technological innovation within the classroom. Although computer literacy is becoming increasingly important for teacher effectiveness (Selber, 2004), many teachers continue to feel threatened by technologies that they have not mastered (and that some have not even tried). As educators sometimes struggle to engage today’s technology-savvy students, allowing students to serve as technology trainers can be an excellent way to provide teachers with some high-tech strategies that will captivate students and get them involved in teaching and learning. Generation Youth and Educators Succeeding (Generation YES) is a national nonprofit organization based in Olympia, Washington, that does just that via GenYES, a program wherein students learn complex computer skills, lesson plan design, and instructional strategies so that they can serve as trainers for K-12 educators.

Teachers could learn much from their young students, many of whom possess a great facility for the manipulation of technologies of all kinds. When willing to learn from their students, teachers could not only model the learning process for their students but also validate the students’ sense of self-efficacy, the affirmation of which has been shown to enhance student learning in itself (Hoyt & Ames, 1997).

Academic Support and Education Technology

By Angie Dodson

Another part of facing the challenges that accompany the incorporation of ed tech as a part of curriculum is providing academic support to students in their access and use of technology. Providing academic support for students’ use of technology means overcoming barriers to the implementation of ed tech in the learning process at the district, school, classroom, and community levels. Awareness and plans for meeting these barriers lay the foundation for successful integration and use of technology as curriculum supportive of student 21st-century academic growth.

Barriers to the integration of ed-tech range from the availability and access to technology, to the knowledge and skills needed to use technology, to the attitudes and approaches toward the utilization of technology. Districts, schools, teachers, students, and their families all contribute to creating a learning environment where students have the opportunity to learn 21st-century skills, engage in critical thinking and problem-solving, and feel supported in their journey.

Districts and Schools

Awareness of the educational needs at all levels is foundational for effectively planning and supporting ed tech in curriculum. Districts and schools need to know what employable skills are in demand, what equipment, software, and programs are available and the cost, the technology needs of their students in terms of access to devices, internet, available bandwidth, and use. They also need to be familiar with the knowledge and skill levels of the teachers, administrators, and staff to make the most efficient and effective decisions about what technology is used, under what circumstances it is used, and how to support that use technically and economically. Some districts fund equipment and applications for all schools such as issuing laptops to all students, creating computer labs in schools, equipping classrooms with a designated number of computers or laptops, video display units, Smart boards, headphones, microphones, speakers, etc., and some implement the bring-your-own-device approach where students may utilize their own phones, laptops, iPads, etc. for use in the classroom and at home. Districts and schools also subscribe to particular learning management systems such as Schoology, Google Classroom, Canvas, or Moodle, particular software or online packages such as MS Office Suite to streamline the approach and access to learning material and resources. Additionally, districts and schools may also have bots for homebound students, and other assistive technology available for meeting specific physical, mental, or emotional needs of students. Finally, districts and schools need to orchestrate a vertical alignment of ed tech goals and learning objectives from P-K through 12 that encompass the development of needed technical skills including but not limited to keyboarding, word-processing, creating spreadsheets, developing multimedia presentations, searching, emailing, and coding.

Teachers

At the classroom level, teachers need to be aware of all the resources available to them through their school and district, the technology goals, standards, and learning objectives they are expected to teach, as well as their approach to incorporating ed tech into their classroom. Additionally, factors for successful and meaningful implementation of ed tech that supports students academically include:

- awareness of their attitude toward the use of technology in their classroom,

- their own technical skill level, training, and support opportunities available to enhance those skills,

- their overall approaches to teaching educational technology to their students, and

- the technological needs of their students all.

How technology is used in the classroom is “closely aligned” with teacher pedagogical beliefs (Ertmer et al, September 2012). A study conducted on this correlation indicated that despite other barriers (adequate resources, training, and support), the degree to which technology is used and integrated into the classroom is influenced more by teacher attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and skills surrounding technology than any other barrier (Ertmer et al, September 2012). With this in mind, teachers need to assess these factors, think about how this impacts their technology integration, and what is needed to fill the gaps to make sure students are being offered the appropriate opportunities and the needed support to develop their 21st-century knowledge and skills. The proceeding outlines ways in which this can be accomplished.

- Articulate the philosophy and rationale for the use of technology in teaching/education. This helps pinpoint one’s specific attitude and beliefs about teaching with technology while revealing why.

- Outline strategies to support the implementation of this philosophy in light of ISTE educational standards, state standards, and/or district and school expectations.

- Determine what barriers exist in the implementation of these strategies.

- What are the parameters for tool use in terms of availability, capability, and access by students?

- How much training time is needed and available for utilizing the tools and associated applications?

- What kind of support (IT, administrative, departmental, family) is needed for implementation and use of the technology, and is it readily available?

- Develop a plan for overcoming those barriers.

- Utilize school and district resources especially for equipment, software, training, and support.

- Survey student skills levels, experience, and home access to technology.

- Bring in other teachers, skilled parents, and experienced students for support.

- Gradually implement technology beginning with what is easy and naturally supports what is already being done in the classroom.

- Build the needed skills before expecting advanced use.

- Incorporate measures to lessen digital fatigue.

Digital/E-learning Fatigue

With meaningful implementation of ed tech also comes the potential for digital or eLearning fatigue. Digital or eLearning fatigue occurs when learners reach a saturation point of online learning and are no longer able to effectively learn from the use of digital tools (Fighting E-Learning Fatigue in 5 Ways: Adjusting to the New Normal, 2020). Signs of digital or e-learning fatigue include physical effects such as eyestrain, headaches, muscle tension, tender ears, and overall exhaustion (Remo, 2020); emotional effects including anxiety, depression, and boredom; as well as mental effects such as lack of attentiveness, decreases in motivation, and increases in stress (Balram, 2020).

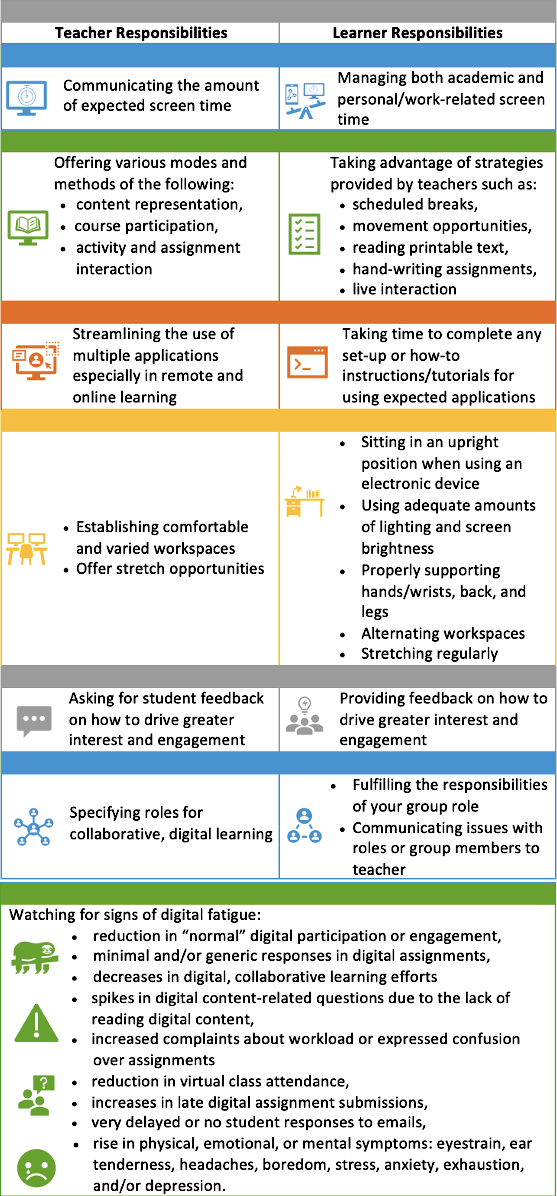

The responsibility for lessening the effects of digital learning fatigue can be shared through action taken by both teachers and learners.

Downloadable Version of Figure 15:1 – Teacher Responsibilities and Student Responsibilities

Taking a proactive approach to lessening digital fatigue along with identifying and overcoming barriers to technology integration can greatly support students academically as they learn and engage in 21st-century practices.

ILA 15.0

Access the following sample surveys to determine how you might use them to survey students and parents about technology integration. Post your thoughts in the ILA Response Group in Hypothesis.

Assessing the Potential of Digital Fatigue

21st-Century Skills Assessment

Sample 21st-Century High School Skills Assessment

Assignment 1 – Word Processing

Compose a five-hundred-word personal essay of three to five paragraphs on a topic of your choice (or as assigned by your teacher) using a word processor. Share the document with your teacher as an e-mail attachment, using a shared folder or through Google Docs.

Assignment 2 – Spreadsheet Use and Graphing

Create two spreadsheets to the following specifications:

- Conduct an informal poll of at least ten of your classmates about an issue or preference (for example, their favorite drink at lunch, such as milk, water, a sports drink, or juice). Enter your data into a spreadsheet and use the data to create a bar graph or pie chart that is labeled.

- Create a spreadsheet containing the following data for a class play that gives a running balance of profits or loss and calculates the number of tickets that need to be sold in order to break even.

Expenses

$1000 – Scripts and royalties

$500 – Sets and props

$300 – Costumes

$200 – Piano accompanist

$100 – Program printing

Income

$500 – Program advertisements

$300 – Donation from student activity funds

$5 per ticket sold

Assignment 3 – Multimedia Presentation Software and Digital Image Handling

Create an original slide show of at least six slides on a single topic. The slide must be organized, have a consistent style and format, and include both text graphics. Submit a printout of the slides.

Assignment 4 – E-Mail Use

Send an e-mail to the teacher who gave you this assignment. Attach a word-processed document that answers the following questions:

- What does the concept “limited right to privacy” mean in school and business settings?

- What precautions should one take when opening an attachment and why?

- What do “spam” and “spoofing” mean, and how do you protect yourself from them?

- Should the same rules that apply to verbal harassment in school apply to e-mail? Why or why not?

Teaching in Times of Crisis

From Vanderbilt Center for Teaching

Whether local, national, or international in scope, times of crisis can have a significant impact on the college classroom. The students need not be directly related or personally involved to experience anxiety or trauma. While proximity (a local event) may lead to a more obvious impact on your students, the effects can be just as difficult based on “the sheer magnitude and scale (national events with wide media coverage)” and “the degree to which students are likely to identify with the victim(s) of the tragedy and feel like ’vicarious victims’” (fellow students, fellow women, fellow members of a group targeted by a hate crime, fellow Americans) (Huston & DiPietro, 2007, p. 219).

The resulting anxieties students—and teachers—bring into the classroom in response to a crisis can affect student learning, as documented by psychological, cognitive, and neuroscience research. Individual crises, such as coping with the loss of a family member or recovering from a difficult break-up with a significant other, can affect an individual class member’s learning and performance. However, communal crises, such as the unexpected death of a fellow student or teacher, the shock of 9/11, the devastation of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, the tragedy of the shootings at Virginia Tech, or the bombing of the Boston Marathon, can affect everyone’s well-being—personal and academic.

“It is best to do something.”

A 2007 survey by Therese A. Huston and Michelle DiPietro (2007) reveals that “from the students’ perspective, it is best to do something. Students often complained when faculty did not mention the attacks at all, and they expressed gratitude when faculty acknowledged that something awful had occurred” (p. 219). Students report that “just about anything” is helpful, “regardless of whether the instructor’s response required relatively little effort, such as asking for one minute of silence…, or a great deal of effort and preparation, such as incorporating the event into the lesson plan or topics for the course” (p. 216). The exception, the least helpful and even most problematic responses are a “lack of response” and “acknowledging that [the crisis] had occurred and saying that the class needs to go on with no mention of opportunities for review or extra help” (p. 218).

There are many possibilities for how to address a crisis in class, from activities that take only a moment to restructure your entire course, and plenty in between. Again, consider that students appreciate any action, no matter how small.

“The general conclusion, from the students’ perspective, appears to be ‘do something, just about anything.” —Therese A. Huston & Michele DiPietro

Taking a Moment of Silence

Taking a moment of silence interrupts a course very little but gives everyone a chance to reflect as a part of a community and demonstrates the instructor’s sense of humanity.

Minding the Cognitive Overload

Such events affect students’ cognitive load, as “working memory capacity is reduced immediately following an acutely stressful experience” (p. 218). This awareness may lead you to be lenient with due dates or adapt your syllabus for the week following the crisis to accommodate a reduced workload, both in terms of introducing new concepts and expecting students to exercise typical study habits. Holding a review session for material covered during the crisis may also be helpful.

Assigning Relevant Activities or Materials Huston and DiPietro cite specific activities that helped students cope after 9/11: “College students who participated in a journal writing exercise or who listened to a story that addressed themes relevant to the terrorist attacks showed greater improvements and fewer signs of trauma” (p. 209). Consider how you may “use the lens of [your] discipline to examine the events surrounding the tragedy,” such as assigning a relevant poem, connecting it to a similar historical moment, or examining the engineering concepts involved in a relevant structure (p. 219).

Facilitating a Discussion

If you would like to talk directly with your students about the crisis, you might consider contacting the school or campus counseling services for ideas on how to approach such a conversation. Additionally, the information below may also be useful in discussing a tragedy with your students. Several factors can affect how a conversation about a crisis might go. As Deborah Shmueli (2003), a professor at Haifa University in Israel, has suggested, some things to take into consideration are as follows:

- students’ perceptions about how the crisis has affected them personally;

- students’ perceptions about others whom they consider to be affected;

- issues deemed important to each person or group;

- institutional, financial, and other impediments to successful communication;

Taking these factors into account, researchers and practitioners who study communication make the following suggestions for difficult conversations (Chaitlin 2003):

Consider how much time the conversation might take.

Teachers who wish to create safe places for communication need to consider how much time a difficult conversation will take and how much time they can provide for that conversation within the semester. Since a single conversation may not be enough to address the issue fully, teachers should be willing to be flexible, extending the conversation into future class sessions or over the course of the semester, as needed. The teacher should allow enough time for each conversation so that students who have difficulty opening up to the class or who need time before they can begin talking about their experiences may also be included.

Acknowledge both verbal and nonverbal communication.

In a discussion or conversation, silence can make a teacher feel uncomfortable, but silence and other non-verbal behaviors can be just as vital to a productive conversation as words are. It is tempting to fill the silence with variations on the question asked, but doing so can inhibit students’ abilities to think through the issue and to prepare to share their thoughts with their classmates. If students repeatedly need extremely long silences, however, the teacher should invite conversation as to why students do not feel comfortable sharing with their classmates.

Let students set the ground rules.

Allowing students to set the ground rules not only can help students create a space where they feel safe to share their thoughts, emotions, and ideas, but can also help students find power at a time when the crisis has left them feeling powerless. Ground rules should be set before the conversation begins and reiterated every time thereafter that the conversation is continued.

Encourage students to be empathetic listeners.

In conversation, people are often thinking about what they want to say in response rather than fully listening to the individual who is talking. In addition, if the crisis at hand is difficult to handle emotionally or if classmates feel defensive, empathic listening becomes all the more challenging. Pointing out such dynamics to students can at least encourage them to think about their positions as listeners.

Allow freedom of participation.

If students feel uncomfortable, allow them to leave. If they feel coerced into the conversation, then they are likely to withdraw from the conversation or guard closely what they say.

Balance the power in the classroom as much as possible.

Ensure that no one student or group of students has more rights than others and take care that all receive equal respect.

Provide a predictable forum.

For continuing conversations, provide a format and space that is familiar and predictable for your students so that they feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts and experiences.

You may even want to identify or even facilitate a way to help those most affected by the crisis, such as collecting money, donating goods, volunteering to help at the crisis site, or other ways of supporting rescue and relief efforts. Such “problem-focused coping” is among the most helpful responses identified by students and one explanation for the “lower levels of long-term stress” among people “indirectly affected” by 9/11 (Huston & DiPietro, 2007, p. 216-218).

Remember that it is not necessarily your role to help students through the crisis, and, in fact, it may be counter-productive for the students if you bring up emotionally difficult issues without providing appropriate support and assistance. Refer to the proceeding resources.

Providing Resources

If you are unsure of your ability to provide emotional support but feel the need to show that you are aware of its impact on your students, acknowledge the crisis by providing your students with resources for dealing with it. Below are a few suggestions:

- Ask a professional from the campus, school or community counseling services to come talk to your students.

- Provide the class or student with the contact information for local counseling, support, or action centers.

- Share with students the APA’s “Students Who Have Experienced a Crisis” if there has been a natural disaster, or an act of violence, or individually if a student has experienced a loss. This primer contains ideas for teachers to help maintain a healthy classroom environment.

Additional Resources

- “Working with the Emotionally Distressed Student”: A booklet from the Counseling and Psychological Services of San Diego State University

- GrievingStudents.org: Website from the Coalition to Support Grieving Students with resources and advice for how to respond to students dealing with loss (written for K-12 students, but the experiences of grief and compassion don’t magically change at 18 yrs old); see this NPR story

Insight 15.2

Curriculum has had a long and varied journey, but with the advent of state-of-the-art multimedia and digital resources, coupled with the seismic shift from brick-and-mortar schools to online learning in the past year, teachers have been challenged to know how to engage students with online learning tools that were unheard of a decade ago. Add to this the disparity between some students having good internet service and digital devices with other students having limited or no internet services and devices and the degree of the challenge to educate all students increases significantly.

There will continue to be expanded learning opportunities for students using dynamic software and collaborative partnerships that extend beyond the school walls to include students from other cities, states, cultures and countries. As teachers, we need to be open and ready to ride this exciting wave of curriculum coupled with technology!

Summary

Teaching has changed as a result of technology and the avalanche of new information, and there is now additional responsibility placed on teachers, students, and parents to have successful learning experiences. Digital citizenship it includes privacy protection, oversharing, cyberbullying, digital footprints and rules, netiquette, and credibility. In addition, the expanded technology standards have led to a shift in how teachers teach, including the challenge of keeping up with technology, becoming skilled in the use and implementation of the latest technology trends, and creating learning strategies to properly equip students. These challenges increase the need for more knowledge, training, and funding of educational technology.

These many changes can also lead to digital learning fatigue by teachers and learners, but there are a number of strategies that can help alleviate this problem to successfully integrate educational technology in support of students’ academic progress.