10 Viral Media: American Studies, Information and Media Literacy, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Karsten Fitz und Florian Zitzelsberger

Abstract

This article turns to the phenomenon of “viral media,” or media content “going viral,” to ask about the necessity and development of information and media literacy in the American Studies classroom. Discussing examples of political communication in the digital age, the article addresses ways of confronting challenges arising from this kind of virality, such as the dissemination of fake news, in American Studies. Juxtaposing theoretical commentary with reflections on pedagogical praxis, based on seminars taught in SKILL.de, the article promotes an exchange between American Studies, information and media literacy, and the COVID-19 pandemic as cornerstones that shape the experience of teaching and studying English in the present moment. Focusing on these intersections can contribute to an understanding of viral media more attuned to changes in media use, (social) media environments, and their impact on the lived experiences of users as individuals as well as collectives in times of crisis.

Introduction: Virality, Trump, and the Infodemic

In her “AIDS and Its Metaphors” (1989), the companion to the earlier “Illness as Metaphor” (1978), Susan Sontag examines the metaphors used to communicate disease – and how these metaphors become the means through which we engage with both the disease itself and those affected by it. Among the most prominent examples of such metaphors are what Sontag calls “military metaphors”, which we may construe as an interrelated set of metaphors pertaining to the same frame or indexing the same kind of narrative: disease becomes an “invasion of alien organisms, to which the body responds by its own military operations, such as the mobilizing of immunological ‘defenses’” (Sontag, 2002, p. 95). With diseases – or the viruses that cause them – being regarded as an attack on or assault of the body, it is perhaps unsurprising that this rhetoric of the body mobilizing its defenses is easily displaced: Where Sontag once described the role of military metaphors in the “stigmatizing of certain illnesses and, by extension, of those who are ill” (p. 97), Donald J. Trump declared war against COVID-19 during the early stages of the present pandemic, an attempt at reclaiming the agency lost to the uncontrollable spread of an at the time relatively unknown virus. The scope of the metaphor eventually shifted from fighting a battle to its outcome, as well as from body to state, with the only viable option through the pandemic for the United States being to emerge victorious: “And it will be a complete victory. It’ll be a total victory” (Trump qtd. in Bates, 2020, p. 4).[1]

Such metaphors therefore play an important role in the construction of identity by contrasting self and other. In the case of the military metaphor, self and other are characterized by their opposing (non-)agential positions: one is the invader, one gets invaded; one attacks, one is attacked. However, Trump’s use of the metaphor does not constitute a mere reversal of the logic that undergirds the narrative of aggressor (the virus) and victim (the United States). In his evocation of exceptionalism – “when we win the war […][;] it’s ‘when,’ not ‘if’” (qtd. in Bates, 2020, p. 10) – Trump plays into larger cultural narratives and as such constructs several others against which the self is expected to fight. That Trump is not solely declaring war against SARS-CoV-2 becomes most salient in his use of “Chinese virus” (qtd. in Bates, 2020, p. 6). This metaphor conflates several interrelated others discursively linked to “Chinese” (source domain) onto the “virus” (target domain), including China as the alleged origin of the virus as well as individuals whose association with the virus is predicated on essentialist, nationalist, and racist assumptions. The war against the virus is thus tied to xenophobia, implying that the virus is dangerous because it is foreign, and characterized by an anti-immigration bias, with the spreading of people becoming synonymous with viral contamination.[2] As such, Trump’s use of the war metaphor, together with its extension of the “Chinese virus,” operates in the service of othering: What some may rationalize as rhetorical scapegoating or brush off as an insensitive remark based on supposedly ‘exotic’ eating habits—the zoonotic virus was for a long time assumed to have spilled over from bats to humans by way of consumption—actually produces material effects in the world, evidenced by the increase in racist anti-Asian rhetoric and violence in the United States around the time Trump first used “Chinese virus” on Twitter (see Reja, 2021).

Trump’s tweets have themselves gone viral. They have been retweeted or shared across platforms tens of thousands of times within a matter of minutes. (It should be noted, however, that the omnipresence of the “Chinese virus” is not only due to the rapid spreading of Trump’s tweets, but also increased by his status as President of the United States at the time.) The phrase ‘going viral’ or ‘viral media content’ has been accepted into common language use by many to describe the rapid, uncontrolled spreading of media content as the result of the affordances of digital and social media as well as the internet more generally. In ways not dissimilar to the other examples, ‘viral media’ functions as metaphor. However, it does not describe the virus as much as it turns it into a metaphor itself. In other words, the ‘virus’ becomes the source domain in this constellation whose valences are transposed onto ‘media’ as the target domain. A discursive history in which viruses are linked to technology and information supports this metaphor; think, for example, of computer viruses or malware more generally. Sontag also briefly considers this metaphor use: “So far as ‘plague’ still has a future as a metaphor, it is through the ever more familiar notion of the virus. […] Information itself, now inextricably linked to the powers of computers, is threatened by something compared to a virus” (2002, p. 155). While one can only speculate about the meaning behind the co-occurrence of viral metaphors and viral epidemics/pandemics, Sontag notes how the “omnipresence of talk of AIDS” at the time of writing has “partly stimulated” the increase in “metaphors drawn from virology” (p. 155). And while such statements remain limited to critical observation and inference, we can still acknowledge how viral metaphors foster an awareness of virality, which subsequently reinforces the omnipresence of the epidemic or pandemic situation through language.

In “Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things In Between” (2022), Joseph Osmundson turns to this contemporaneousness and shows what the relationship between viral media and the COVID-19 pandemic means for our decoding of the metaphor, that is, how the context in which we now inevitably use the metaphor adds to its meaning: “Viruses – and going viral – promise us just exactly what COVID-19 demonstrated in early 2019: exponential growth seemingly without limit” (p. 44). He further explains this connection:

This exponential growth, too, is seen in the ability of information to flow via the Internet: if one person shares a video, and then three people share that video, and then each one of those people who receive it has three people share that video in turn, you can reach an unprecedented number of eyes and minds in an astonishingly short time. (p. 43)

It is noteworthy that Osmundson frames the velocity and impact of viral media as the ‘promise’ of going viral, a possibility akin to the reality of the pandemic. This framing is rather ambivalent considering how a promise is usually formulated as a positive – “I promise you (not) to . . .” functions as a social contract which we are meant to rely on and which can be redeemed – while a negativity hovers over the promise itself: Exponential growth may resonate with people looking for their fifteen minutes of fame online, but the association with the COVID-19 pandemic urges us to ask at what cost this can be achieved. In this sense, Osmundson’s framing allows us to see how viral media have perhaps always been an ambivalent phenomenon. For example, while social media posts going viral can contribute to the accumulation of (social) capital, turning successful social media influencers into “celebrities in pockets” (Hauke & Zitzelsberger, 2020, p. 87), it is difficult to control these posts once they are shared, downloaded, and reposted, sometimes without context or within a new context that alters their original meaning. This uncontrollability goes even further since most posts cannot be sufficiently fact-checked because of the sheer amount of content produced, published, and (re-)distributed online every second of the day, which allows for misinformation or fake news to spread more easily (or for disinformation to pass among other content).[3] As An Xiao Mina (2019) notes, this development is in part a byproduct of what she calls “intentional overproduction,” meaning that if content producers deliberately want to go viral, they have to maximize their output until they “find[] the right narrative” that “sticks” (p. 73; original emphasis).

Part of what makes misinformation and fake news harmful – even if they are not intended to cause harm – is the lack of literacy in media users, combined with a certain susceptibility we may link back to the idea of the ‘promise’ of going viral and the influencer culture that sustains it: Especially those who grew up with YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and the like are used to trusting the (content produced by the) social media influencers they follow, based on the promise of intimate exchange (Abidin, 2015) that, however, remains an empty one, an illusion, like any parasocial interaction (Liebers & Schramm, 2019). Such one-sided relationships also explain why users may not be aware of the possibilities of manipulation and misinformation when they engage with content online, because for them, this impression of intimacy (mis)construes social media as an ostensibly private – and safe – space. This susceptibility is therefore hardly new, even if the virality of social media now comes into view under a slightly different premise informed by the events of the last three years. (In line with this, it is noteworthy that there seems to be a growing skepticism of the presumed gatekeeping practices of ‘established’ media that is contrasted by the impression of a democratic ‘unfilteredness’ on social media, which has led Trump to label the former, including verified factual reports, as ‘fake news’ or ‘fake media’.) As Tara Brabazon (2022) argues, the age of Trump, which, when it comes to going viral, intersects with the age of COVID-19 in significant ways, “did not invent misinformation online. The lack of information literacy – the capacity to read, assess, sort and sift – has been logged as a challenge in the online environment for well over a decade” (p. 69).

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic has made the call for appropriate literacies more pressing because of the innumerous fake news and conspiracy theories surrounding it, including speculations about the origin of the virus, like the aforementioned example of the bats or the “Chinese virus,” as well as how pandemic agents like the virus itself or vaccines affect the body. A time characterized by “ruggedly individualist truth-telling,” as exemplified by Trump himself, Jayson Harsin (2020) calls the COVID-19 pandemic an “infodemic” to “signal[] a distinctly cultural aspect of the virus’ impact, since information implies human relations of mediation (media) and communication” (p. 1061). The infodemic has highlighted (and continues to do so) the importance of literacy not just in determining whether a source is reliable; if left unquestioned, statements like Trump’s suggestion to inject disinfectant to treat COVID-19 (BBC, 2020) can cause significant damage, especially if we consider the context of communication and the (political) authority ascribed to the communicator. It has also shown that media users are not well equipped to navigate the flood of information during the pandemic, especially if public figures (ab)use their authority to spread false information, which resulted in social media platforms intervening by flagging incorrect or unverified information and “barring users ‘from posting misleading information about the coronavirus, including denials of expert guidance and encouragement of fake treatments’” (Reuters qtd. in Harsin, 2020, p. 1060). Similar reactions could be witnessed to Trump’s tweets concerning the, as he alleged, ‘rigged’ outcome of the 2020 presidential election. His account was eventually suspended permanently on grounds of “Glorification of Violence” after the Capitol attack in January of 2021 (Twitter, 2021).[4]

Changes in media use (including online behavior and users’ susceptibility and skepticism toward media content), media environments (including the affordances of digital and social media), and the socio-political contexts in which media take on new roles that more immediately impact on the lived experiences of users as individuals as well as collectives (including the COVID-19 pandemic and threats to democracy during the Trump presidency like the Capitol attack or the discrediting of election results) necessitate the formation of new literacies. These literacies need to be both adaptable enough to change with these developments and attuned to confronting the medial, social, cultural, and political challenges of the infodemic. In addition to the examples discussed above, much of the content that goes viral (like memes or remixed audio bites added to TikToks or Reels on Instagram) cannot always be attributed to a concrete source. Discussing political memes, Wayne Journell and Christopher H. Clark (2019) argue that, because “authorship and intent are difficult to trace” in such cases, since they likely miss any identifying information or metadata (in contrast to tweets, for example), “they cannot be analyzed using the same techniques as traditional forms of media” (p. 109). Memes and other viral media content thus “pose unique challenges for teaching about media literacy” (p. 109). Part of these challenges also lies in how we understand information and media literacy (IML), which needs to be regarded as processual, not static or closed off. IML can therefore only ever aspire to be a “provisional label” whose “demarcations are malleable” (Holze & Zitzelsberger, 2022, p. 80): What makes the approach to IML developed at the University of Passau special is its interdisciplinary design through which it is uniquely equipped to transform the boundaries of its own toolbox (integrating various literacies), how we understand media, and the position and agency of media users as they shift from critical reception toward informed, media-conscious prosumption.

In this article, we center ‘viral media’ to ask about the necessity and development of IML in the American Studies classroom and suggest that both viral media and the present pandemic offer lenses through which IML can be effectively addressed. Discussing examples of political communication in the digital age – from presidential lies and alternative facts to pandemic metaphors and hashtag activism – in their medial, cultural, and historical contexts, we look to IML as a way of confronting some of the challenges arising from viral media, such as the dissemination of fake news or conspiracy theories. In this, we respond to Brabazon’s (2021) assessment of the current information landscape as one where, similar to Harsin’s infodemic, “[w]ithout powerfully theorized humanities, lost in representational and identity politics, ‘fake news’ survives as a mantra because of the lack of attention to information literacy” (p. 7). In the following sections, we therefore juxtapose theoretical commentary with reflections on pedagogical praxis to promote an exchange between American Studies, IML, and the COVID-19 pandemic as cornerstones that shape the experience of teaching and learning English in the present moment – and to demonstrate ways in which their intersection can feed back into our understanding of the phenomenon of viral media.

Lies, Fake News, Counternarratives: Storying (Not Just) in the Digital Age

Eric Alterman begins his most recent book, “Lying in State: Why Presidents Lie and Why Trump is Worse” (2020), with the words: “I hardly need to make the argument that Donald Trump is a liar. Neither is it news that previous presidents have also lied quite a bit” (p. 1). And, of course, it is no news either that Donald Trump used social media, most extensively Twitter, to reach and radicalize his followers, a process in which many of his tweets – and those of many of his fans and supporters – went viral. American Studies is concerned with this phenomenon of viral media and virality and how this relates to political communication, because this leads into the very heart of what this field of study is concerned with at its core: The production of narratives with the purpose of ‘storying’ an event or a persona – and the deciphering of such representations in their constructedness. And no other persona is more important in American political communication – probably in global political communication per se – than the American president (Cornog, 2004; Fitz, 2015). Indeed, even though Donald Trump might be an exceptional case in this context (as in many others) – Alterman (2020) even calls him a “pathological liar” (p. 2) – it is true that all American presidents have used lies for different purposes: out of necessity in crisis situations of national security, for opportunistic reasons, or as a means of self-protection. In fact, one of the core stories about the first president, George Washington, the so-called “Cherry Tree Episode”, indicating the allegedly unequaled honesty and uprightness of Washington already as a very young boy, is a complete invention.[5]

Alterman describes a sort of ‘tradition’ of presidents lying to the American public, a tradition which also includes almost all of the most highly revered and publicly appreciated among these heads of state. This began with Thomas Jefferson, who deceived the nation with regard to the purpose of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) by calling it a scientific exploration rather than a colonial enterprise of land acquisition. During World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt publicly pretended to be hesitant to enter the conflict with Hitler Germany, while secretly supporting the British cause and preparing the U.S. involvement. Not long after that, his successor Harry S. Truman falsely declared the Japanese city of Hiroshima a ‘military base’ – with devastating consequences. John F. Kennedy, no doubt the greatest political hope of the immediate postwar period, lied about the Cuban missile crisis and led the world to the brink of a nuclear world war. The biggest ‘liar in state’ to date before Trump is, of course, Richard Nixon, who claimed to know nothing about the break-in at the Watergate building, the Democratic National Committee headquarters, in June 1972, and the secret wiretapping of the political opponent, an incident which helped coin the infamous term Watergate – and prompted the president’s resignation in order to forestall his impeachment. Less politically dramatic, but just as effective in terms of publicity, was Bill Clinton’s impeachment for lying about his (consensual) sexual relationship with the White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

Both in terms of quantity as well as quality of his lies, however, none of the 44 presidents before and the one after him so far have been able to trump Donald Trump. From his claiming during the Republican primaries that he personally saw thousands of Muslims in New Jersey celebrating the attacks of 9/11, to the size of his inauguration crowd, which prompted his advisor Kellyanne Conway to fabricate the now-famous term ‘alternative facts’, to his verbose insisting that COVID-19 will suddenly ‘disappear’ because he wants it to, to continuing to maintain to this day that he was cheated out of office in the last presidential election, Trump has taken lying to the public to a new, dramatic, and sometimes tragic level. He has, as Michael Blake (2022), Professor of Philosophy, Public Policy and Governance, has pointed out, also taken lying to a new intensity level, because, unlike most of his predecessors in office, who at least lied in the (frequently self-perceived) service of some central public good, Trump mostly merely narcissistically defended his own self-image.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt (1978) has pointedly addressed the consequences of lies in the realm of politics:

If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. […] And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please. (n.pag.)

In the polarizing political U.S. environment since Trump announced his first presidential candidacy in 2015, the echo-chamber effect of the online world in general, and of social media in particular, has immensely contributed to generating political support on the basis of ideology rather than on rational reflection and facts. In this climate, viral media have begun to play the role of solidifying the ideological leanings on both sides of the aisle, but certainly much more so in populist communities, among which supporters of Trumpism are the most visible and audible ones. This process can even have a brainwashing-effect, particularly when every factual message or information that does not fit into the ideological framework is continuously dismissed as ‘fake news’ by the ‘fake media’, but only in order to use this accusation to spread the own mis- and disinformation (Ross & Rivers, 2018). As Arendt (1968) has stressed in her essay “Truth and Politics,” which first appeared in “The New Yorker” in 1967:

It has frequently been noticed that the surest long-term result of brainwashing is a peculiar kind of cynicism – an absolute refusal to believe in the truth of anything, no matter how well this truth may be established. In other words, the result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lies will now be accepted as truth, and the truth be defamed as lies, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world – and the category of truth vs. falsehood is among the mental means to this end – is being destroyed. (p. 257)

The gradual destruction of such dichotomies as truth vs. falsehood that are meant to help distinguish fact from lies, for instance, has also been observed by Tracy Simmons (2018) who considers how the term ‘fake news’ itself is expressive of the uncertainties and ambivalences this development may cause. The term, she argues, “has become commonplace” since the presidential election in 2016 and Trump’s inauguration in 2017, but has been effectively displaced in its meaning: Rather than signifying wrong information, “the phrase is misunderstood and wrongly used by many news consumers. It has been used by politicians to insult reporters, by officials to deny threatening news reports and by observers who do not want to hear what is being reported because it conflicts with their opinions or values” (p. 255). In short, the term has transformed from a rather descriptive debunking of de facto false news reports, or mistakes in reporting, drawing our attention to how such ‘news’ are ‘fake’ as in fabricated, to a rhetorical strategy of dismissal, a prescriptive, and preemptive, assessment of factually valid news as ‘fake’ – thus “discredit[ing] the mainstream media” (Simmons, 2018, p. 255) – that leaves little to no room for counterarguments.

A prominent example for fake news going viral was reported by Sapna Maheshwari for “The New York Times” on November 20, 2016, twelve days after the election of Donald Trump. In this case it was not a purposefully produced wrong message by hackers in Russia or by a political supporter run amok, but, quite on the contrary, a seemingly neutral but misinformed social media post by Twitter user Eric Tucker in Austin, Texas. Tucker thought he had seen paid protesters being bussed to demonstrations against President-elect Donald Trump just one day after the election. As Maheshwari puts it, “[i]t is an example of how, in an ever-connected world where speed often takes precedence over truth, an observation by a private citizen can quickly become a talking point, even as it is being proved false” (n.pag.). Tucker, who up to this point had about 40 followers on Twitter, posted a tweet with three completely unspectacular images, which did not hint at any political context whatsoever, of what he believed were buses with anti-Trump protesters (fig. 1). It was sent with the caption “Anti-Trump protestors in Austin today are not as organic as they seem. Here are the busses they came in. #fakeprotests #trump2016 #austin.” Within no time, the post was shared 16,000 times on Twitter and more than 350,000 times on Facebook. On Reddit the tweet generated more than 300 comments within hours, some of which blamed the liberal billionaire philanthropist George Soros, who is frequently targeted by right-wing conspiracy theorists, to be the initiator and financier of this ‘protest’. By the next morning, several conservative online discussion fora and blogs spread the misinformation further and in the course of the day the local Fox News television station would get involved (fig. 2). In spite of the fact that the bus company was contacted by Austin’s Fox 7 and denied having been involved in transporting protesters, and although Tucker admitted in interviews that his post was just based on a wrong assumption, the essence of which he did not research at any point, the message was not unmasked as the fake news it was. Rather, by the end of the second day, Tucker was counter-factually referred to as ‘eyewitness’ by the conservative blogosphere and the fabricated connection to George Soros’s money was shared on Facebook 44,000 times.

Upon deleting the original tweet and posting an image with the word “false” on it (fig. 3), Tucker received only 29 retweets and 27 likes, demonstrating that the political discourse in the U.S. today is highly ideologized and polarized and that for many people the ideological political stance overrides factual truth. The lacking engagement on Twitter also shows the little influence the average social media user has on their content going viral (or not); for the post to spread, it has to “stick,” to use Mina’s term (2019, p. 73), and whether something sticks largely depends on the (cultural/political) narratives that are already in place. Virality thus in part hinges on how media content aligns with, or can be (mis)construed as aligning with, said dominant ideological political stance.

Since American Studies investigates the literary themes, multicultural histories, cultural and political ideologies, and cultural productions of the United States, the ‘making legible’ and decoding – as well as, ultimately, understanding – of these viral media messages within their socio-historical and political contexts is part of the discipline’s raison d’être. Raising awareness among our students in the teacher training program to recognize the constructedness and, as in the above example, potential or actual falseness of such viral messages and narratives, is an important part of our responsibility as university teachers. After all, it is those students who are going to educate and prepare future generations of school children to be ready for the challenges of (political) communication in the digital age.

Significantly, the examples of presidential lies and fake news show that the principle concern with storying – in the sense of creating narratives based on shared values, which themselves come to form the foundation of these values – is not just a disciplinary fixture of American Studies. As Henry Steele Commager (1967) argues, “[n]othing in the history of American nationalism is more impressive than the speed and the lavishness with which Americans provided themselves with a usable past: history, legends, symbols, paintings, sculpture, monuments, shrines, holy days, ballads, patriotic songs, heroes, and – with some difficulty – villains” (p. 13). Storying has shaped American self-understanding from the very beginning, both culturally and politically (think of how American independence and democracy themselves are narrated and memorialized; see Fitz, 2010), in ways that are inextricably linked to the media. Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” (1983), for example, offers an explanation of how media establish ‘nation’ as ‘community’ by crafting a story around it, not just in the sense of Commager’s usable past as history, but also as the story of comings and goings, of past, present, and future. The media thus play an important role in establishing social coherence and allowing the individual to feel and identify as part of a community despite the fact that “the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members” (Anderson, 2006, p. 6). Given the continued relevance of these concepts for understanding the United States, especially for those whose impression of U.S. customs and values is mainly representational, the question arises how digitization affects this process of storying and identity formation. In the following, we share two spotlights from our work in SKILL.de to show that, while digital means and media of storying differ from ‘traditional media’, many of the phenomena we now commonly associate with the digital age – like fake news – are, in fact, not entirely new but carry with them a long discursive and medial history that contributes to their wide dissemination today.

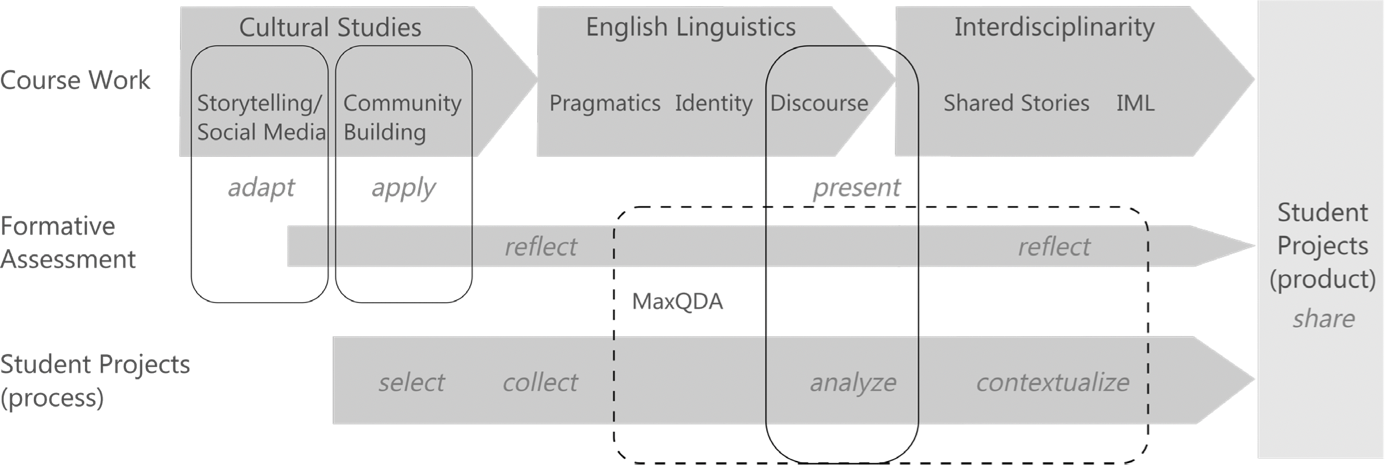

Spotlight 1: Sharing Stories and the Stickiness of Online Social Movements

How do the affordances of social media impact on the stories that are told both individually and collectively, and how do they shape the discourse of that collective? How can we understand processes of community building in online environments that are less strictly limited by national and geographical boundaries? How is identity constructed online and how are we to account for the connection between online and offline identities? Are social media more democratic than other media? How do individuals participate in society via bottom-up processes if these mainly happen in the digital realm? By extension, how do social movements travel between online and offline worlds? These are some of the questions we addressed in the seminar “#Activism and Social Media Movements: Political Communication in the Digital Age” (summer 2020), which brought together the fields of American Studies and English Linguistics to offer an interdisciplinary approach to hashtag activism and social media. As shown in figure 4, students engaged with these questions in three larger modules dedicated to cultural studies, linguistics, and their intersection. The work on asynchronous modules on the platform ILIAS and our synchronous discussions were accompanied by a portfolio that offered scaffolding for students’ final projects: For example, in the first module, students were asked to adapt linear models of storytelling in a way that meets the affordances of digital and social media, which allowed them to reflect on how storying on social media results in – and depends on – a changed understanding of producer and consumer, and what role interactivity plays in this regard. In line with this, the other modules aimed at developing competences (listed here in italics) that would later contribute to students’ independent studies of hashtag activism. These studies worked with a large corpus of tweets (analyzed with the help of the software MAXQDA) to offer conclusions about how the social media movement at hand operates both culturally (e. g., how does it relate to hegemonic cultural discourses?) and linguistically (e. g., how is this stance conveyed?).

Hashtag activism is a form of “discursive protest on social media united through a hashtagged word, phrase or sentence” (Yang, 2016, p. 13). Linking this phenomenon to political communication, we were particularly interested in the “power of digital activism in shaping public discourse” (p. 13). As examples like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo illustrate, hashtag activism can extend beyond the digital sphere, but it does so first and foremost by growing a movement online before it can effectively ‘spill over’. In other words, these movements bring people together based on their shared grievances, from which a shared story emerges. According to Donna Hancox (2019), storying subsequently can become a means of

giving voice and meaning to the experiences of groups and communities who have previously only been represented by others rather than determining their own forms of representation. The belief that stories have an important role to play in social change has an abiding place in many organizations and social movements, and continues to define the philosophy of contemporary activism. […] In part, what drives these types of storytelling projects is a belief that having the opportunity to tell their own stories empowers individuals and communities, and that sustainable change occurs from within empowered communities. (pp. 333–34)

These stories, as collective practices and forms of empowerment, are shaped by their digital environment, which has been linked by scholars like Henry Jenkins (2006) to a democratic promise because of the bottom-up processes they facilitate, turning consumers into producers.[6] In “Narratives Online” (2018), Ruth Page additionally considers how social media thus bring people together via the stories they tell or, in Page’s words, the stories they share. In understanding hashtag activism to build on shared stories, this class explored how individual micro-stories (like singular tweets) both reflect and shape the macro-frame of the shared story with which they align themselves via the use of a hashtag, signaling, and contributing to, “shared attitudes between its tellers” (Page, 2018, p. 18). For a more detailed account of shared stories as hashtag activism and its implementation in this class, see “Teaching as Sharing: Hashtag Activism and Information and Media Literacy” (Holze & Zitzelsberger, 2022), which also offers a case study of the #MeToo movement and considers how the co-occurrence of hashtags is indicative of a shift toward more intersectional concerns.

Here, we are interested in the capacity of hashtag activism to go viral and perform resistance to dominant cultural discourses. If what ‘sticks’ is usually in line with an existing narrative, then how likely is it that shared stories that dissent from this narrative go viral? As counternarratives, the shared stories told by movements like #BlackLivesMatter are not in line with the ideologies that undergird what we referred to as dominant cultural discourses or existing narratives. However, they nonetheless relate to them, even if this means taking an opposing stance, because they are concerned with the real-life experiences of individuals affected by these ideologies. Indeed, such movements do not form randomly or out of nowhere, nor are they inventions of social media. Rather, they are motivated by events in which the voices of those eventually participating in hashtag activism remain unheard. Sharing stories – raising one’s voice – becomes a necessity when those in power fail to condemn, and continue to condone, violence perpetrated against minorities. It is no coincidence that #BlackLivesMatter went viral after the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor (Reese, 2022). The movement thus not only makes everyday racism and microaggressions visible on a larger scale, it also uncovers the effects of systemic racism in a way that can no longer be passed over: Tied together by a common hashtag, voices continue to accumulate; despite biases in the algorithms of social media platforms, the use of the hashtag – as a searchable item or metadata – will show up statistically. The example of hashtag activism thus demonstrates that virality entails a certain relation to (not necessarily conforming to) a discourse or narrative relevant to the time and place of construction that is ‘sticky’ enough to assemble a large variety of voices around it, which is facilitated by both the technical affordances of social media and the porousness of its borders, with the potential for participation exceeding the (geographical) confinements of the events that spawn the movement.

Spotlight 2: Fake News Aren’t New – and Neither Are Conspiracy Theories

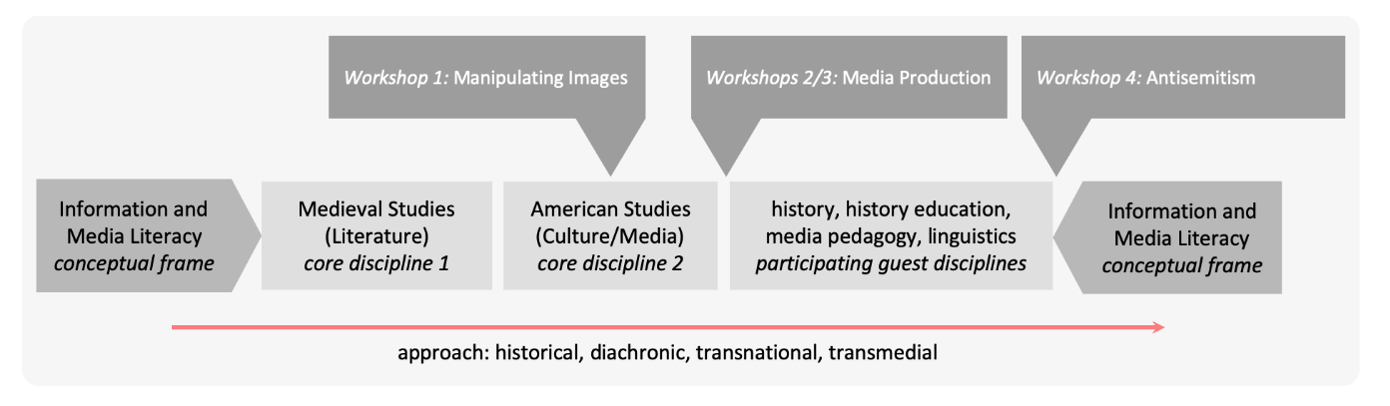

In a class on propaganda, conspiracy theories, and fake news (winter 2021/22), a collaboration between American Studies and Medieval Studies (Ältere Deutsche Literaturwissenschaft), students also turned to counternarratives. However, in contrast to those encountered in the class on hashtag activism, the ones covered in this class are usually understood to be counterfactual. Our main interest – spawned by the perceived surge in conspiracy theories and fake news in recent years – were the reasons why such forms of knowledge spread and how they transform the contemporary information landscape. While a first guiding hypothesis may suspect digitization to play a vital role in this regard, and while it surely does influence the way knowledge is produced and disseminated, a look into the history of these phenomena illustrates that they are hardly new. That the terms we associate with them seem new to us in part has to do with the cultural function these phenomena performed throughout time, which is to say, the phenomena predate their contemporary terms of engagement, they have accrued a certain connotative meaning over time: Discussing U.S. American conspiracy theories, for example, Michael Butter (2014) demonstrates how what we now readily perceive as illegitimate knowledge has until the 1960s been considered a legitimate form of knowledge (p. 9). Our goal in this class was therefore to better understand the relationship between ways of knowing and ways of distributing knowledge – how we can learn from the history of conspiracy theories and fake news (including propaganda) to better account for their contemporary uses. Digitization then becomes one among many factors that contribute to and facilitate the spread of conspiracy theories and fake news because of both the technical affordances of digital and, especially, social media and the epistemological shifts it engenders, examples of which we already outlined above (see Harsin’s concept of the infodemic as an era of “ruggedly individualist truth-telling”).

With this class, we mainly offered students an open discussion forum with a strong interdisciplinary focus (fig. 5): With six disciplines in total sharing their perspectives on one or more of the key terms of the class (and an additional workshop on the role of antisemitism in conspiracy thinking by the Anne Frank Zentrum Berlin), students were asked to document class discussions in the form of a collaborative digital concept map to visualize (dis)continuities between the different approaches discussed. The result – an interdisciplinary, diachronic, transnational, and -medial network – provides orientation regarding both the topic of the class and the complex conditions of the perceived omnipresence of conspiracy theories and fake news in the digital age, where the perspective of any of the disciplines involved would necessarily fall short because of digitization being an overarching phenomenon. Besides the (il)legitimacy of these forms of knowledge, common questions or themes included the use of fake news and conspiracy theories as rhetorical strategies of delegitimizing, discrediting, and deflecting, which hints at the role of the third key concept of the class – propaganda, the exertion of power/influence over public opinion, an originally neutral term as well – that helped us to situate such rhetorical strategies historically and in the context of political communication.

The recurring questions and themes generated insights regarding the development of the key concepts of the class as well as their interrelation. For example, the core disciplines of this class both focused on witches and witch-hunts in their respective sessions to demonstrate the contribution of propaganda and religious prosecution to conspiratorial thought in medieval Europe (Tschacher, 2001, pp. 52, 74); the Puritan import of this kind of conspiracy thinking to New England (and its consequences, most notably during the Salem Witch Trials); and the rhetorical adoption of the witch-hunt as a metaphor in political communication in the mid-twentieth century, including the Communist witch-hunts under Joseph McCarthy during the Second Red Scare. (The accusations made in either of these cases, and especially their function in deflecting, show similarities to what is nowadays subsumed under the umbrella of fake news.) With a focus on literature, the class examined propagandistic writings (e. g., Heinrich Kramer’s “Malleus Maleficarum”, 1486) as well as dramatizations of conspiratorial thought (e. g., Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown,” 1835, and Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible”, 1952) with the aim of contributing to students’ acquisition of IML by engaging with texts produced in different times and locations as well as with varied pragmatic purposes. In turn, the focus on literature can provide tentative conclusions about the contemporary status of propaganda, conspiracy theories, and fake news:

The first indicators that the status of conspiracy theories in American culture was about to change can be traced back to the 1950s. Whereas nineteenth-century authors [such as Hawthorne] were unable to escape the logic and appeal of the conspiracy theories surrounding them, Arthur Miller could step outside conspiracy discourse and analyze it from a distance and without condoning the validity of conspiracist claims in his 1952 play The Crucible. (Butter, 2014, p. 286)

By exercising IML in the discussion of literary proximity or distance to conspiratorial thought, working with these texts helped prime students for identifying conspiracy theories or fake news by providing them the means necessary to assess and critically reflect on information and media. Our approach to IML strongly emphasized the cultural and historical dimensions of information as well as its medial form and as such depended on the interdisciplinarity of the class, its instructors and guests, and students. We highlight the relevance of interdisciplinarity for IML below. More information on this class is available on the DiLab Blog.

Literacy Matters: Teaching and Learning in the American Studies Classroom

In a more recent book on conspiracy theories, Butter (2018) calls for more social literacy as a strategy to counteract the dissemination of conspiracy theories (and we may add fake news here as well). Such a social literacy, he argues, needs to integrate, or be complemented by, media literacy and historical literacy (p. 229). The approach to IML at the University of Passau arguably consists of these literacies, albeit in the form of constructivity, culturality, and historicity as aspects through which media take shape and which shape our engagement with (the world through) media. Butter’s call for social literacy emphasizes why IML is so important: it is a “prerequisite of responsible citizenship” and as such participates in “political education” (Holze & Zitzelsberger, 2022, p. 80). In this section, we contextualize our previous remarks on viral media and American Studies within the framework of IML and highlight some of the teaching formats through which we implemented IML in the American Studies classroom.[7]

Generally, IML pursues the goal of establishing a conceptual framework for the competent handling and critical use of information and its medial and technological mediation contexts. More particularly, IML seeks to provide teachers and learners with the ability to generate and communicate knowledge and its contexts as a basic requirement for a responsible participation in today’s global social and economic system, in which digital media play a fundamental role, which still is not nearly acknowledged widely enough nor adequately understood both didactically and pedagogically. Our work in SKILL.de (and the precursor SKILL, which originated this approach to IML) is guided by this observation and has aimed at developing, and implementing, innovative teaching and learning formats, specifically in the realm of teacher education. We addressed this goal in a consistently interdisciplinary manner, because the complexities and framing conditions of digital media narratives and cultural products cannot be understood in a monodisciplinary way. As a discipline, American Studies is engaged in this kind of dialogue not only because of the fact that the internet as such, as well as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and the iPhone, are American inventions; it has also always been a highly interdisciplinary field of scholarship that has simultaneously examined American literature, history, society, and culture since its founding in the 1940s. (And it goes without saying that technologies and media cannot be understood outside of cultural, societal, political, economic, and social contexts.)

The knowledge, skills, and abilities to be developed by IML are not directly oriented towards a specific teaching profession. Rather, they are oriented towards pedagogical practice in a variety of fields of organization and implementation of formal and informal teaching and learning processes, in which the topics of media, mediality, and digitization become pertinent. Permeating all areas of society and the world we live in, the irreversible omnipresence of these topics in teaching practice poses a yet unresolved challenge to pedagogical standards of professionalism. And the rich discourses around digitization as an interlocking technological and sociocultural transformation process generate new educational demands on the school ecosystem, demands which can best be addressed from an inter- and transdisciplinary vantage point. This digital scenario poses completely new challenges in terms of content, curriculum, didactics, and methodology, and especially in terms of media pedagogy.

The homo medialis is constitutively bound to a medium (or several media) in experience, cognition, reflection, and action, which can be understood to be ‘mediated by media’ more literally. In a broad media-anthropological sense, there is consequently no non-mediated world encounter, world knowledge, world interpretation, and world treatment in the relationship of humans to the world. Rather – according to the media-anthropological position underlying the IML theory as much as the discipline of American Studies – world encounter, world experience, world knowledge, world interpretation, and world treatment take place indispensably by means of media representation(s) and construction(s) and/as ‘resonances’ of world. Put another way, if culture, according to the central basic assumption of American Cultural Studies, represents the web of meaning, i. e., the set of all contexts of meaning that are possible in a society, then such a drastic change in forms of communication as has taken place and is still taking place as a result of the digital revolution, according to this understanding, also causes a transformation of culture as such. A media-cultural approach means, by implication, that culture in the digital society is permeated by media communication in temporal, spatial, and social terms. Media, be they natural media such as the human body and its senses, artificial media such as signs and symbols, technical media such as tools and prostheses, subject-bound media such as experiences, personae, and biographies, or social media such as analog and digital mass (communication) media – all are media and media constellations that are not only placed between humans and the world. All these media are – mostly in combination – indispensable for experiencing, learning, recognizing, interpreting, and interacting in the world. Mediality is thus the basis of all articulations and transformations of human world- and self-relations. In the digital information, knowledge, and media society that permeates all world relations, homo medialis becomes homo digitalis. And because American Studies as an academic discipline has made it its mission to understand and interpret American cultural products in their respective socio-historical contexts, IML necessarily plays a fundamental role in contemporary American Studies.

We may thus summarize the relationship between IML and American Studies in reciprocal terms of engagement: (1) IML is a necessity if we are to understand and engage meaningfully with cultural phenomena. This concerns both our lives, in which we experience or encounter them, and the American Studies classroom, in which their implications for and effects on culture, media, and society are negotiated. (2) If American Studies depends on IML because of its critical focus, which includes processes and practices of storying and representation, among others, then the American Studies classroom can become a space for the acquisition of IML. It is important to us, however, not to treat IML as a given or as the byproduct of, say, literary and cultural analysis as which it is often treated. While IML will most likely immediately resonate with people in the field (and be recognized as something they are also implicitly concerned with), it has been a central concern of our work in SKILL.de to make IML visible and address the processes through which – and why – IML is exercised in the classroom to make students actively aware of the skills they are developing and how these skills can in turn be applied to other learning and teaching scenarios. We provide concrete examples for the implementation of IML in the American Studies classroom in Spotlight 3 below.

Coming back to our examples of viral media, we see how this reciprocity plays out: IML is required to engage with viral media responsibly and to resist their coercive effects (1). Viral media are not just your average funny cat videos, gifs, or memes. They can also be tied to a political agenda as we have seen in the case of lies and fake news going viral. Here, virality – or, more specifically, the omnipresence of the respective viral media content – threatens to distort the perception of media users, which may be instrumentalized for a political cause. In this sense, the examples addressed above are not entirely dissimilar to historical instances of propaganda, even though viral media often lack an apparent motivation or intent that may be claimed ex post facto to build a message around (we previously used the word ‘(mis)construe’ in this context) media content that serves a specific purpose. Because virality is, for the most part, uncontrolled, and because (social) media users are likely to be exposed to a wide range of viral media content, IML is also important in assessing not only the verisimilitude of media content, but also its broader implications for society and culture.[8] The example of viral pandemic metaphors has shown how viral media content can contain seriously damaging messages, which gain traction in society because of their visibility: Viral media, or in this case viral metaphors, seem to accumulate a sense of truth by means of repetition. By ‘truth’, we do not necessarily mean that the message communicated suddenly becomes factually correct or verisimilitudinous. On the contrary, the accumulation of truth here is meant to invoke the normalization of these messages as an iterative process. The “Chinese virus”, for example, is of course based on a false (and racist) assumption. However, it has quickly become narratable, sticky enough for people to latch onto this kind of rhetoric, because of its context and the manner of its distribution: As the communicator, Trump legitimates and valorizes this kind of rhetoric qua his position as president in a most visible manner on Twitter, allowing his tweets to go viral, which in turn has been taken up by mainstream media and news coverage, contributing to its omnipresence. To speak with Sara Ahmed (2019), the “Chinese virus” has become a well-trodden path that eases the passage for those who come after (in this case, after Trump); “[t]he more a path is used, the more a path is used” (p. 41). IML can help us understand how this path has acquired its shape over time and empowers us by providing us with the means of creating new paths that do not subscribe to, or reproduce, xenophobia and racism. As Osmundson (2022) puts it:

One way to use up harmful metaphors of The Virus is to ask if they are true to begin with. COVID-19 kills. […] But viruses exist all around us, always. Most of them do us no harm. To generalize, to make metaphors and narratives, from the only deadly exceptions as opposed to the benign rule is just one lazy way to not quite tell the full truth. (p. 36; emphasis added)

If left unquestioned, metaphors like Trump’s “Chinese virus” – and this applies to viral media more broadly – can have serious consequences on individuals in society. Because metaphors operate with mental images that “defin[e] our everyday realities” (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003, p. 3), the passages opened by them invite similar patterns of thought and action. The increase of anti-Asian violence in the United States since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic thus attests to Sontag’s observation that the virus itself may not always be the most severe threat: “The metaphors and myths, I was convinced, kill” (2002, p. 99), and they effectively can because of how they render those exposed to them susceptible to their implicit messaging to which IML can serve as an antidote.[9]

While viral media certainly require users to be information and media literate, the American Studies classroom can offer a safe space in which the encounter with viral media can be made productive for the development of IML (2). As Simmons (2018) notes, by “learning to identify the differences between truth, satire, falsity, dislike, error, and learning why fake news has gone viral, individuals can enhance their media literacy skills” (p. 255). In our work during SKILL.de, we have made it our goal to add to this more reception-oriented assessment of the role of viral media in the formation of IML different approaches that empower students as users of media in both educational and non-educational contexts. These approaches, which we will elaborate on in the first of the following spotlights, include teaching and learning formats specifically geared toward IML and the role of students as future teachers (of English); the use of digital media like podcasts to create an environment in which students can learn with and about media; and the production of media content as the basis of an extensive reflexive engagement with the properties of media and the means of constructing, representing, distributing, and archiving information they offer.

Spotlight 3: Learning With/About Media

The class on propaganda, conspiracy theories, and fake news discussed above is not just a regular co-teaching seminar. As shown in figure 5, the class consisted of many disciplines whose focus in research and teaching exceeds that offered by American Studies and Medieval Studies – as the inviting, core disciplines – significantly. However, despite their differences, all participating disciplines were brought together by IML as a conceptual framework that allowed them to exchange ideas and make them fruitful for interdisciplinary discussion. We thereby followed a format originally conceived in SKILL, the Information and Media Literacy Think Tank, which we set out to develop further in SKILL.de. According to Sarah Makeschin (2019), the format has been developed to offer students in teacher training a space to explore ways of becoming a responsible agent in the contemporary information landscape (p. 166). Notably, the format is intended as operating across hierarchies, meaning that students, research associates, assistant and full professors would come together and discuss a certain topic and its relevance to today’s information and knowledge society, particularly in educational contexts, at eye level. In such an environment, students are taken seriously as experts in their own right, with the majority of each session dedicated to discussion or workshop-like scenarios. It also takes into consideration students’ interdisciplinarity by working across disciplinary boundaries; as students enrolled in teacher training, they all major in more than one discipline. The IML Think Tank has been co-organized by American Studies twice during SKILL.de. In addition to the course outlined in the second spotlight, we offered a class on “Canonization and Historiography: Digital Archives” (winter 2020/21), which dealt with knowledge production in the digital age and how knowledge – as well as what kind of knowledge – is made available to teachers and students in schools through institutionalized (like schoolbooks and official curricula) and non-institutionalized digital resources (e. g., Open Educational Resources).

In both cases, students developed skills relevant to IML by both engaging in critical discussion (reception-oriented) and producing their own media content (process-oriented), which they subsequently reflected on by consulting the relevant scholarly literature regarding the topic of their project and by reconstructing, and retelling, their production processes. In so doing, students become aware of their own construction of meaning, the means and media by which this is achieved, and the demands of a specific target audience; we also discussed student projects in groups, for example by offering digital gallery walks, which provided students with the opportunity to receive peer-feedback on their projects. As such, conscious and critically informed media production contributes to the processual acquisition of IML by transforming students’ role as media users whose media consumption and production merges. This is also vital in how we understand the role of teachers in the digital age: Not only will our students need to be(come) information and media literate, they also need to be(come) competent prosumers as they design materials – educational resources – for their classes. The kind of prosumer imagined here does not have to constantly produce their own materials. Rather, they need to be adept in the selection, adaptation, combination, remixing, etc. of media to contribute to the learning of their future students. The class on canonization and historiography put these skills to use on a meta-level by putting students in the position of those who determine what knowledges will be archived. Engaged in the selection of information and making accessible previously underrepresented knowledges, students explored the mechanisms of canonization at the same time as understanding how media shape this process. More information about our contributions to the IML Think Tank can be found in the respective episode of the SKILL.de-podcast Mit & Über.

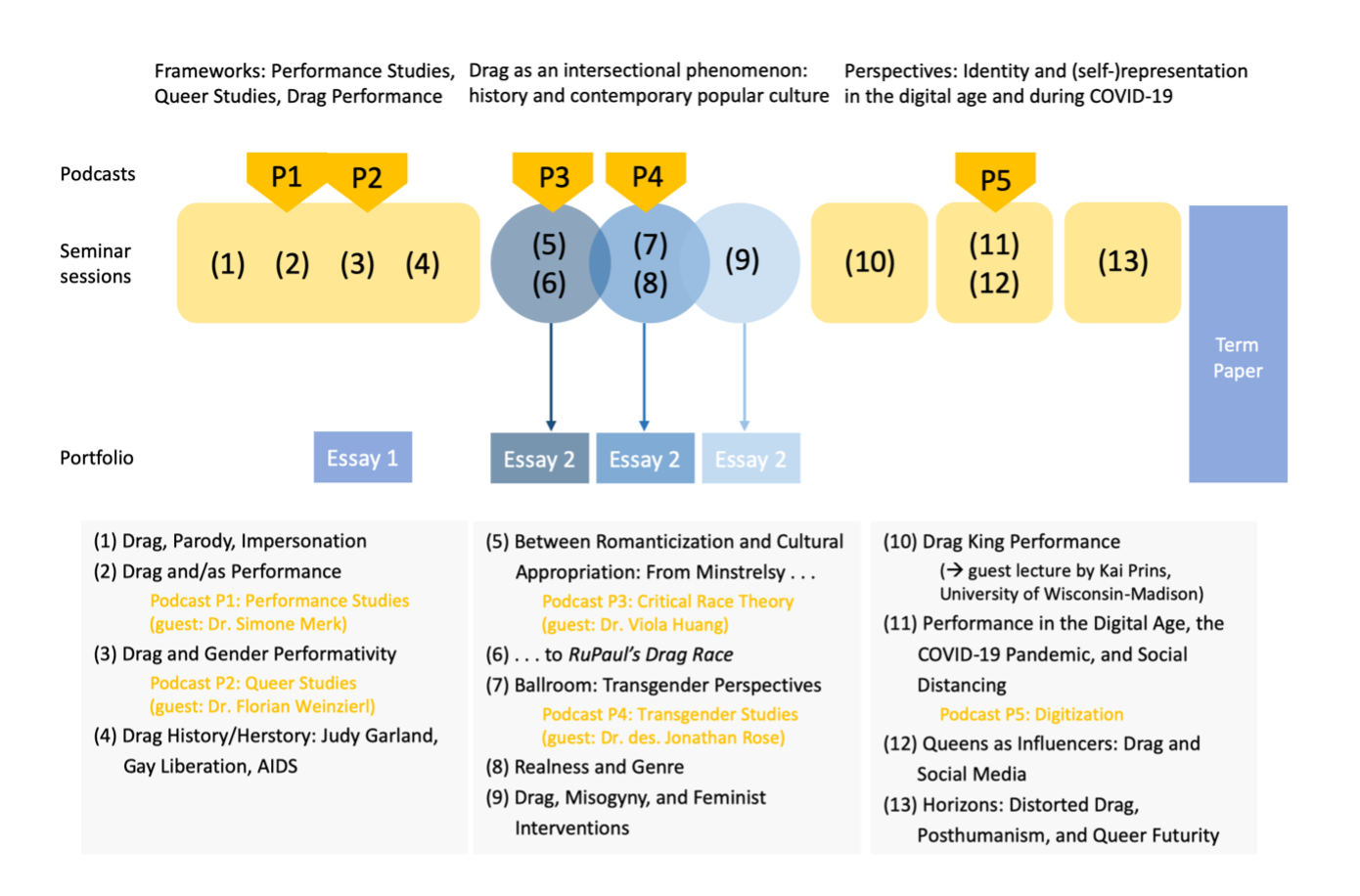

The goal of learning with and about media by fostering a positive attitude toward media prosumption is not just a standard to which we hold our students; it is also a challenge we embraced ourselves by implementing media production in our pedagogical praxis. For example, the seminar “Drag Performance in the United States: Pasts, Presents, Futures” (winter 2020/21) used podcasts to complement other teaching materials like secondary literature and primary sources. Expert interviews with scholars from the University of Passau and beyond served as the basis for podcasts that linked relevant theories (like approaches in performance studies or queer studies) to the contents of the class or that provided critical perspectives for them (including insights from critical race theory and trans studies). Figure 6 shows how the individual podcasts relate to the course schedule. Since this seminar was held exclusively online due to lockdown measures, the podcasts helped in providing guidance and structure for students. Because they were based on expert interviews, they also substituted for some of the reading that would otherwise be assigned, which was beneficial to alleviating stress and reducing workload during a time when students felt under a lot of pressure to perform well academically while being burdened by the experiences of the pandemic. This seminar also took other measures to support students without compromising their learning processes. Discussing drag as a performance genre intersectionally, students were asked in groups to specialize in one of the social contexts pertinent to the history and development of drag in the United States – including race and racism, transness and transphobia, and gender and sexism/misogyny – for which they served as experts, in turn allowing us collectively to chart intersections without neglecting the specificities of either of these contexts.[10] As also shown in figure 6, students wrote two essays during the semester before working on a final term paper, with the second essay drawing on their work on the respective expert group topic. The class implemented a peer-review process for these essays such that students were able to revise their work before handing it in officially, which proved to be effective in shaping and enhancing their arguments and was conducive to developing an intersectional way of thinking.

Taken together, all of our classes offered during SKILL.de and their shared interest in learning with and about media – for example, through media prosumption – as well as a thematic focus on viral media phenomena not only attest to the necessity of IML in the American Studies classroom, they also show how the American Studies classroom can become a home for IML to emerge.[11] As most of our classes additionally centered questions of diversity and identity in their topics, the interplay of media reception, reflection, and production helped us address the relationship between (medial) form and (social) norm to enable students to explore, experience, and experiment with different ways of meaning-making within and beyond (cultural) hegemonic frameworks (Knapp & Zitzelsberger, 2022, p. 68). These meaning-making strategies have changed significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic because of the increased relevance and role of – as well as reliance on – media, particularly of domesticated media as opposed to mainstream or mass media (Brabazon, 2021, p. 11), which has impacted world encounter, world knowledge, world interpretation, and world treatment in ways that have left traces well beyond lockdown periods. In the following, we hence address how we have taken up the COVID-19 pandemic in our teaching in a spotlight of two seminars.

Spotlight 4: From AIDS to COVID-19

When we began our work in SKILL.de in 2019, we could not have possibly anticipated the direction we would eventually take. Within the larger project, American Studies and English Linguistics formed a research and teaching cluster that thematically centered around political communication in the digital age, which we initially addressed in two interrelated objectives: political participation through (social) media (in the seminar “#Activism and Social Media Movements”) and IML (see also Wawra in this volume). The pandemic situation made us adjust the focus of our work since most (also non-political) communication was now made in the digital realm and because of the increased urgency with which politics were communicated: Digital media were instrumental in informing the public about safety measures, changing legal situations, etc. during a public-health crisis. At the same time, we witnessed a considerable growth in the spread of fake news, misinformation, and conspiracy theories, sometimes via the same channels. Understanding this growth in response or as a reaction to not only the pandemic itself but also the (communication of) measures taken to flatten the curve, it becomes apparent that such phenomena are not merely an outgrowth of social media; above all, they are culturally specific. In the context of the United States, we therefore need to situate this observation in relation to the growing polarization of society and with it the respective interpretation of individualism as a core value of American culture on either side of the political spectrum, attesting to the centrality of culturality as a pillar of IML. For example, whether a mask mandate is perceived as beneficial to common good correlates with how individualism is understood: Am I keeping myself (and others) safe by wearing a mask – or does wearing a mask limit my freedom? In other words, depending on the line of argument, “American individualism [becomes] an obstacle to wider mask wearing in the US,” as studies show (Vargas & Sanchez, 2020, n.pag.). At the same time as we were interested in the present pandemic and the contexts of its mediation, the cultural specificity of responses to COVID-19 draws attention to the (dis)continuities between the present and historical precedents (Waterman, 2020, p. 761), attesting to the importance of historicity as a pillar of IML.

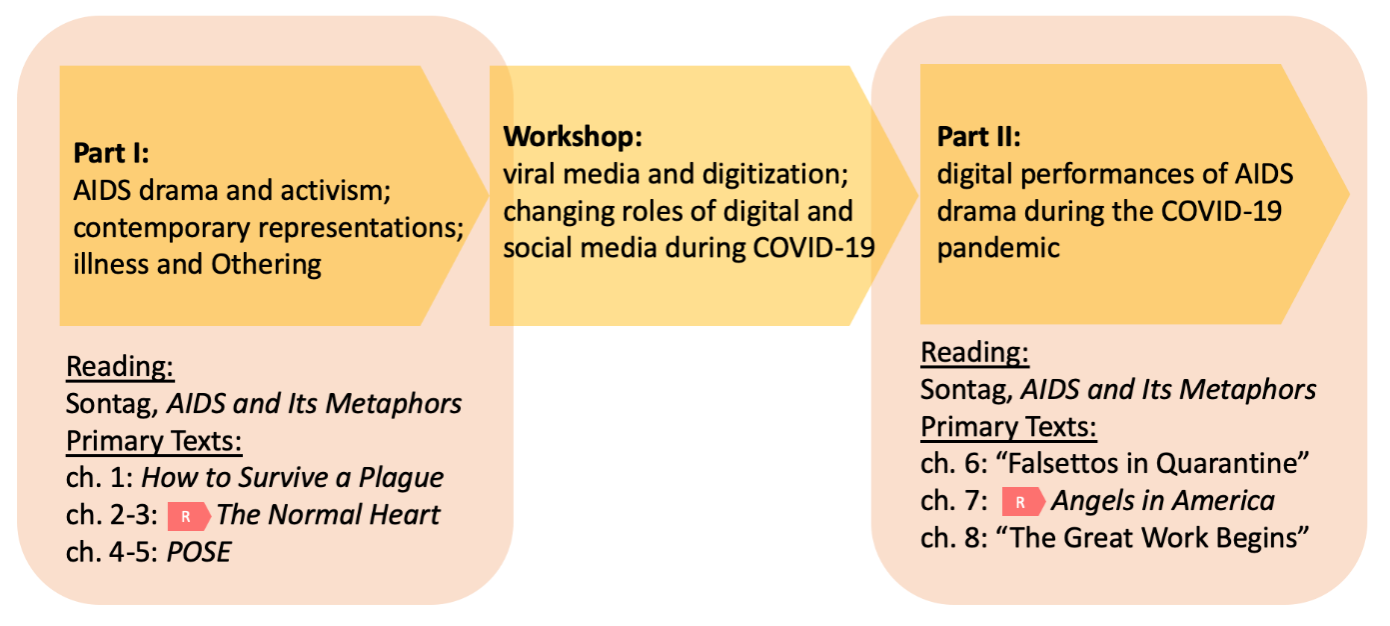

The seminar “From AIDS to COVID-19: Virality and (Dis)Embodiment in US Culture and Media” (summer 2021) addressed the role of the media in shaping public consciousness and political discourse during the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s and during the present pandemic. The metaphor of the virus and, in a workshop linking our discussions of AIDS and COVID-19, of viral media helped us in understanding the transformations pandemic situations engender socially, transforming (group) identity, for example, through othering; culturally, transforming established ways of meaning-making; and medially, transforming the mediation of this experience and the ways in which contact between the groups involved is imagined. Keeping with Bryan Waterman’s statement about how pandemic situations effectively reorient us (by directing us back to prior pandemics), we examined how the presence of cultural texts about AIDS during the COVID-19 pandemic enriches our understanding of both. To establish this dialogue, the class was designed around Sontag’s “AIDS and Its Metaphors”. Students read one to two chapters of the book each week that provided the thematic framework for the respective session (in addition, students were asked to prepare relevant secondary literature on these topics). This framework was then filled with primary sources that resonate with these themes. For example, chapter 5 of “AIDS and Its Metaphors” addresses racialized fear and othering in discourses surrounding AIDS, which was connected to a discussion of the Netflix series “POSE” (season 2, episode 6), in which the effects of such othering are negotiated, and accompanied by an excerpt of Cathy Cohen’s “Boundaries of Blackness” (1999). As part of their portfolio, students wrote responses to Sontag’s text and discussed the role of the metaphors she describes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As shown in fig. 7, the first part of the class focussed on the representation of AIDS in documentaries, drama, and contemporary television series. The inclusion of drama was central to the overall design of the class, not only because “stage plays were at the forefront of the cultural interventions into hegemonic views of AIDS and homosexuality in 1980s’ America” (Haas, 2021, p. 200). The prominence of performance in AIDS activism (which not only includes the stage plays referred to here, but also theatrical protests such as die-ins) and the shift away from embodiment and toward digital, disembodied protests during the COVID-19 pandemic under the precept of social distancing and other lockdown measures also provided one of the main objectives for the second part of this class: to investigate the cultural work of digital performances of AIDS drama during COVID-19. In line with this theoretical interest, we organized two virtual table reads (“R” in fig. 7) of the AIDS plays discussed in class – Larry Kramer’s “The Normal Heart” (1985) and Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” (1991/1992) – to bring students together despite their physical distance, sharing the collective experience of performance in ways that enable “the creation of (affective) proximity in the face of (social) distance that becomes a testament to the alternative modes of relationality the pandemic requires” (Zitzelsberger, 2022, p. 486). The class ultimately showed that both the knowledge about and experience of pandemics can contribute to an understanding of viral media that goes beyond its technical aspects: Viral media affect people. They transform media users in terms of their situated and world knowledges as well as their engagement with media and their ability to adapt to rapidly changing situations, discourses, and affordances. The workshop linking the two parts of the class therefore addressed how this dialogue between AIDS, COVID-19, and viral media can be made productive for the acquisition of IML.

The final class we want to spotlight here ties in with the opening to this article: Out of all seminars, “COVID-19 and Its Metaphors,” co-taught by American Studies and English Linguistics (winter 2021/22), probably best represents the previously discussed intersections of virality, the COVID-19 pandemic, and IML. Examining pandemic metaphors in the context of digitally transmitted political communication during the COVID-19 pandemic allowed us to consider how the discourse surrounding illness is both medially constructed and ideologically charged; it further provided a platform for discussing processes of identity formation and othering, as well as the interdependency of language and culture via concepts like cognitive and narrative framing or the discursive histories of viral metaphors as outlined in the introduction. The didactic approach for this class was based on four different elements, namely sections dedicated to either of the core disciplines, approaching pandemic metaphors from the perspectives of cultural studies and linguistics, respectively; sections that adopted an interdisciplinary perspective within the framework of IML; workshop-like elements on media production; and students’ own projects, in which they examined the underlying assumptions of COVID-19 metaphors in their cultural and communicative contexts in the form of both a written argumentative essay and a video essay. The format of the video essay was chosen in part because of the visuality of metaphors: With their video essays, students reduced the complexity of their analyses without losing nuance by making use of the properties of videos and the possibilities of video production. From draw-my-life-style videos to TikToks or TV reports, students’ projects showed the diversity of approaches sparked by the same prompt. The competence-oriented form of the video essay (Müller, 2021) contributes to the formation of IML by allowing students to reciprocally engage in media production as well as critical analysis and reflection, learning with and about media. Working on video essays not only leads to a prolonged engagement with the topic, it also offers a valuable perspective on metaphors because of the visual dimension they offer. Design choices thus not only matter in how the video translates, but they imbue the metaphor presented in the video essay with meaning. That is, the video essay already offers one possible interpretation of the metaphor. In their subsequent reflections, students were asked to address this layering of meaning and its potentials for sharing – in the sense of teaching and communicating – knowledge about metaphors and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Through their projects, students invariably also added to our own repertoire of COVID-related metaphors. The metaphors selected include, among others: COVID-19 as an avalanche; (evil) trickster; fire, forest fire, or embers; tsunami; wave. While not all of these metaphors are new or entirely specific to COVID-19 (for example, the frame of natural disasters is rather common in crisis situations and has therefore been adopted for the pandemic, see Charteris-Black, 2021, chapter 3), they nonetheless show that there is a way of talking about COVID-19 that does not reproduce the harmful assumptions of Trump’s “Chinese virus” or the ambivalent rhetoric of military metaphors, without downplaying the severity of the pandemic situation. In other words, if, as we have shown, Trump’s metaphor works because it relies on an available script or narrative, we may turn to other existing images to make sense of the newness of the situation we are experiencing. These metaphors allow us to see the pandemic in a different light, which may be exactly what it takes to imagine – and effect – change on an interpersonal and discursive level. Perhaps being information and media literate also means taking a stance and deciding actively and consciously for or against the use of individual metaphors. More information on this seminar can be found in the respective episode of Mit & Über as well as on the DiLab Blog, where we share select video essays and some of the metaphors students developed on their own during our last joined session: “#ReframeCOVID: The Trodden Paths of Metaphorical Thinking and Finding New Ways Forward”.[12]

Conclusion: Viral Media, a New Metaphor for the Digital Age?

In its juxtaposition of theoretical commentary and spotlights from pedagogical praxis, this article aimed at fostering a productive dialogue between American Studies, IML, and the COVID-19 pandemic as central cornerstones of both our work in SKILL.de as well as teaching and learning English at university level more generally. In assessing three and a half years of work, we found ‘viral media’ to be an apt metaphor to frame the challenges of digitization in educational and non-educational settings, political communication in the digital age, and the infodemic in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The versatility of the metaphor as it is employed here – designating media content going viral as much as (viral) media content about the pandemic – may be used to ask whether viral media as a distinctive metaphor of the digital age becomes diluted through the pandemic/infodemic, or in how far this context adds nuance to the phenomenon it seeks to describe. In this article, we have not offered a set definition of viral media but rather challenged a working definition through the lenses of American Studies, IML, and spotlights from our teaching. While a definition of viral media can still retain its emphasis on the uncontrolled spreading of media content with great velocity facilitated by the technical affordances of the platforms that house this content (as well as by cross-platform exchange), the context of the COVID-19 pandemic highlights other qualities of virality: Viral media, as both a metaphor and an observable phenomenon, describes modes of transmission and transformation that are distinct to a culture of digitization and its practices.[13] Viral media content itself can be seen as the result of an ongoing process of transformation in the sense that it is constantly shared, a transmission that entails the (re)appropriation, (de/re)contextualization, and distortion of the content, which is to say, viral media content is never static but complexly (re)worked and (re)framed on and across platforms. (One could even argue that this mode of transformation in turn prompts the platforms to transform themselves: Similar to how influencers will intentionally overproduce to see what sticks, social media services will change their interfaces to see what creates more engagement. An example that attests to the possibility of housing viral media content being a motivating factor in this regard are the changes implemented on Instagram, which seems to move further and further away from sharing photos and ostensibly privileges video content like Reels, similar to TikTok. Recently, Instagram also introduced a feature allowing users to add sound to photos, a development that plays into this overall trajectory.) Significantly, viral media content also transforms media users through changed patterns of use engendered by the mode of transmission of viral media. In other words, viral media socialize media users differently, not only allowing for a different kind of interaction with media content, but necessitating it. We are thus not just constantly adapting to viral media trends, but are conditioned under their changing terms of engagement.

The perspective of the COVID-19 pandemic that has brought virality into public consciousness under a changed premise thus focuses the definition of viral media more overtly on the media user and their relation to viral media content. In adding the layer of transformation to transmission, we draw on the biological connotations of the term ‘viral transformations’, which not only implies mutations of the viral agent, but also effects change in the organism surrounding it. In centering the relationship between viral media and media users, our approach highlights the relevance of IML: While viral media can contribute to the solidification of ideological discourses and impact on public opinion, it is important to note that not all viral media are inherently bad or harmful. (Nor would it be fair to say that viral media are just funny gifs and memes, for that matter.) What has become clear is that the potential damage viral media may cause in part arises from the interaction of the media user and the viral media content. In other words, while the way we deal with viral media does not absolve potentially damaging content from the malevolent intentions of its producers, the responsible, proper handling of such content allows us to intervene early in the chain of transmission, for example, by reporting misinformation or fake news, or simply by not sharing. As a set of skills specifically geared toward participating and acting responsibly in a constantly changing, increasingly digitized media environment, IML enables us to make such informed choices. It further helps identify the (implicit) messaging of viral media content, its ideological framing, and the contexts of its production and reception.