9.3 Define and describe the principles of ethical conduct

Rina Dhillon

This section is largely based on APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants. Students should take some time to read the relevant sections within APES 110 so as to better understand each of the five ethical principles summarised in this section. These principles indicate how accountants (also referred to as Members) should behave (i.e. ideal behaviour).

There are 5 Fundamental Principles of Ethics under APES 110:

- Integrity

- Objectivity

- Professional competence and due care

- Confidentiality

- Professional behaviour

Integrity

The principle of integrity requires that accountants are ‘straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships’ (Section 100.5a). This means that an accountant, while dealing with accountants and non-accountants, must communicate information surrounding the effect of accounting concepts in a way that does not intentionally mislead or drive behaviours in affected individuals. Accountants should not misrepresent through sleight of meaning – for example using terminology to confuse, or influence other stakeholders in ways that benefit a business or a particular individual, at the expense of another, without their knowledge.

Integrity also implies fair dealing, truthfulness, and having the strength of character to act appropriately, even when facing pressure to do otherwise. Acting appropriately involves:

(a) Standing one’s ground when confronted by dilemmas and difficult situations; or

(b) Challenging others as and when circumstances warrant, in a manner appropriate to the circumstances.

In other words, accountants/auditors should not be associated with information that:

(a) Contains a materially false or misleading statement;

(b) Contains statements or information furnished recklessly; or

(c) Omits or obscures information required to be included where such omission or obscurity would be misleading.

Keeping It Real: ASIC win in Westpac super row threatens banks’ cross-sell model

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s victory in a dispute with Westpac over unlicensed financial advice poses a revenue threat to other large financial services firms including Commonwealth Bank.

The landmark decision of a Federal Court full bench to grant ASIC’s appeal in a case involving Westpac’s rollover of $640 million of customer super balances to in-house funds may dramatically affect the sale of financial products.

A three-judge panel of the court unanimously ruled on Monday that ASIC’s appeal of a 2018 decision finding Westpac’s recommendations to 15 customers to switch super funds did not constitute “personal” financial advice be allowed with costs. It also threw out a counter-appeal by Westpac subsidiary BT Funds Management.

The successful appeal is a major victory for the regulator, which had been hoping to use its dispute with Westpac Securities and BT Funds Management as a “test case” providing clarity on the legal line between personal and general advice.

If general advice is not dead, then it’s on life support.

— Michael Vrisakis, Herbert Smith Freehills

It potentially also poses a revenue threat for financial services firms, particularly the large bank-owned vertically integrated wealth managers, and could affect their ability to market and cross-sell investment products via branches and call centres relying on the general advice allowance under the law.

The threat is particularly acute for Westpac – which has announced it is exiting the business of face-to-face personal financial advice, but is retaining BT’s superannuation and funds management business – and Commonwealth Bank, which has shelved plans to divest from wealth management. NAB and ANZ by contrast are selling both investment management and financial advice.

Justice Jacqueline Gleeson ruled in December 2018 that Westpac was in breach of its duty to provide financial services “efficiently, honestly and fairly”, but she did not find that the recommendation to transfer the balances to Westpac-owned, BT-branded funds constituted personal advice.

ASIC alleged that the telephone-based campaigns of Westpac’s so-called Super Activation Team, commenced in 2014, crossed the line from general to personal financial product advice, which the relevant bank subsidiaries, Westpac Securities and BT Funds Management, were not licensed to provide. It appealed Justice Gleeson’s decision in February 2019.

To give personal financial advice, the provider must be licensed and registered with ASIC and has a fiduciary duty to consider the broad financial circumstances and best interests of a customer when making product recommendations.

General advice, by contrast, is subject to relatively less stringent requirements to consider broad customer needs.

General advice on ‘life support’

The business model of recommending or selling financial products on the basis of general advice, which is widespread in the financial services industry, has been badly injured by ASIC’s successful appeal, according to legal experts.

“If general advice is not dead, then it’s on life support,” Herbert Smith Freehills partner Michael Vrisakis told The Australian Financial Review.

The implications of the judgment were that employees recommending a product to a customer, especially if they have an existing relationship with the firm as was the case with the Westpac rollover, could mean that they very easily “stray into personal advice”, even though they may not be licensed to do so, Mr Vrisakis said.

“Even if you haven’t [strayed into personal advice territory], if the advice relates to a matter of significant financial importance to a client, then you may be treated as not acting efficiently honestly and fairly in accordance with community expectations.”

The experienced financial services lawyer described this as an “evolving standard of fairness” being set into legal precedent as courts test the law for the first time.

While the provision of general advice after this case could still be “viable”, the terms upon which it is provided have narrowed and firms will need to be conscious of broader ethical duties to the customer going forward, he said.

Always be closing

In overturning Justice Gleeson’s 2018 decision, Chief Justice James Allsop, Justice Jayne Jagot and Justice Michael O’Bryan exposed a flaw in the marketing and product distribution strategy of the big wealth managers.

“Westpac’s attempts to have customers transfer funds from their external accounts with other superannuation funds into their BT accounts were carefully calculated to bring about this desired result by giving no more than general advice,” Chief Justice Allsop wrote in the published decision.

“The difficulty is that the decision to consolidate superannuation funds into one chosen fund is not a decision suitable for marketing or general advice … this was personal advice.”

Had customers been given the opportunity to consider their personal circumstances and communicate their acceptance of Westpac’s offer at a later date, then the bank might have avoided the conclusion that it had effectively provided personal advice, Justice Allsop wrote.

“This was, however, not the intended model of engagement,” he said. “‘Closing’ was to take place, if at all possible, on the call over the phone.”

The dividing line

ASIC welcomed the court’s decision, which it said “provides clarity and certainty concerning the difference between general and personal advice for consumers and financial services providers”.

Westpac told the ASX it was reviewing the decision.

The Federal Court’s original finding did not provide ASIC with the ammunition it required to take action against unlicensed personal advice across the industry.

The regulator had described its dispute with Westpac as a crucial “test case” whereby the courts were ruling on Section 766B of the Act for the first time, which should have set out clearly a definition industry, legal advisers and regulators could rely on.

“The dividing line between personal and general advice is one of the most important provisions within the financial services laws. It directly impacts the standard of advice received by consumers,”ASIC deputy chairman Daniel Crennan, QC, said at the time of the appeal’s announcement.

“This is why ASIC brought this test case and ASIC believes further consideration by the Full Court of the Federal Court is necessary.”

An ASIC report released in March found widespread consumer confusion over the definitions of personal and general financial advice.

‘Opportunity to do more’

Justice Gleeson’s 2018 decision had been welcomed by the financial services industry, read not only as a vindication of the existing widespread practice of recommending investment products under a general advice allowance, but also potentially widening that authorisation.

Mills Oakley partner Mark Bland said the verdict had significant implications for the way in which financial services firms engage with consumers, and that it effectively broadened the definition of general advice.

“This judgment presents an opportunity to do more under general advice communication channels, allowing greater personalisation in a single, transactional context,” Mr Bland said, following the initial judgment.

“However, if firms expand their general advice models, they will need to ensure to recognise what is in a client’s best interests and ensure that they are given the appropriate warnings.”

Source: ‘ASIC win in Westpac super row threatens banks’ cross-sell model’, by Aleks Vickovich, October 28 2019, Australian Financial Review

Objectivity

The objectivity principle refers to accountants avoiding ‘bias, conflict of interest or the undue influence of others to override professional or business judgements’ (Section 100.5b). There are three components to this principle:

(a) Bias refers to the inclination to disproportionately favour one entity over another.

A Member may be exposed to situations that may impair objectivity and it is impracticable to define and prescribe all such situations. Essentially, relationships that are bias or unduly influence the professional judgment of the Member should be avoided. An example of a breach of the principle of objectivity can be found here: Determination of the Disciplinary Tribunal of Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Case D-1199, July 31st 2019

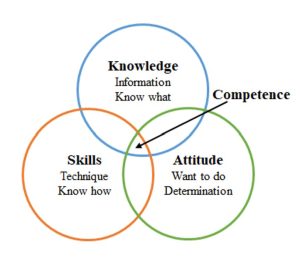

Professional Competence and Due Care

The principle of professional competence and due care requires an accountant to ‘…maintain professional knowledge and skill at the level required to ensure that a client or employer receives competent Professional Services based on current developments in practice, legislation and techniques and act diligently and in accordance with applicable technical and professional standards’ (Section 100.5c).

Keeping It Real: Bondholders launch class action against PwC

The country’s largest blue-chip company auditor, PwC, is facing a class action from bondholders of its collapsed audit client Axsesstoday over allegations of shoddy accounting work by the big four consultancy.

The action, filed in the Federal Court last month, is the seventh time in the past decade that the firm has been sued over its work on audit clients that later collapsed. It has so far settled four of these.

Listed lending company Axsesstoday went into voluntary administration in April 2019 after breaching its loan term conditions and was later sold to an affiliate of private investment firm Cerberus Capital Management for almost $260 million.

But a prospectus given to bondholders in June 2018 suggested Axsesstoday was not at risk of breaching any loan or debt obligations, and those investors now want compensation.

The bondholders allege that the audit giant failed to adequately consider changes to accounting standards that would see the financial assets and liabilities of lenders such as Axsesstoday measured and classified differently.

Expected losses would also be recorded on a prospective basis, rather than the incurred loss model used before the rule change. These changes would ultimately contribute to Axsesstoday’s collapse.

The bondholders allege that PwC either failed to tell Axsesstoday that it had not assessed the likely effect of the rule change on the company’s financials, or wrongly assessed it.

They also claim that by doing the accounting work behind the flawed prospectus, PwC engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

They say that without these misrepresentations, they would not have entered into the bonds.

The lead applicant, Compumod Investments, is seeking damages for the more than $36,000 in bonds it lost when the company collapsed. It had invested in the bonds as trustee for its staff super fund.

Other group members in the class action will also be entitled to damages if their case is successful, though the quantum of these amounts will not be known until everyone who plans to join the action has done so.

Audit issues

PwC failed to raise any concerns about Axsesstoday’s continued survival in its initial audit of the company’s last financial statements before its collapse, but did so in its restated annual report.

In August 2018, PwC signed off on Axsesstoday’s financials without flagging any concerns about the lender’s ability to continue trading.

Axsesstoday shares were suspended two weeks later in September 2018. The initial reason for the halt was for the board to review company strategy, but it was followed by senior executive departures.

At the end of November 2018, the company reissued its annual report to take into account breaching its lending agreements during the 2017-18 period. The restatement cut the company’s net profit and earnings per share in half.

In the reissued report, signed off in November 2018, PwC flagged a “material uncertainty related to going concern” for Axsesstoday.

The newly launched class action is not in relation to this audit work.

The firm settled a case related to its audit work at Centro Properties for around $67 million in 2012, and has also settled cases related to its audits of Provident Capital, Great Southern Finance and Ausbil Investment Management.

It continues to fight one case related to a former audit client, a class action over failed education provider Vocation, in the federal court.

Confidentiality

The principle of confidentiality requires accountants to ‘…respect the confidentiality of information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships and, therefore, not disclose any such information to third parties without proper and specific authority, unless there is a legal or professional right or duty to disclose, nor use the information for the personal advantage of the Member or third parties’ (Section 100.5d). This principle balances the duty of an accountant to ethically maintain the secrets of an organisation, while at the same time acting in the public interest should the need arise. The principle of confidentiality imposes an obligation on Members to refrain from:

(a) Disclosing outside the Firm or employing organisation confidential information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships without proper and specific authority from the Client or employer or unless there is a legal duty to disclose; and

(b) Using confidential information acquired as a result of professional and business relationships to their personal advantage or the advantage of third parties.

Keeping It Real: Pizza accountant to pay $2M for insider trading

A former accountant at pizza giant Domino’s Pizza Inc. has agreed to pay almost $2 million to settle allegations of insider trading from the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The SEC alleges that from 2015 to 2020, Bernard L. Compton traded ahead of a dozen of Domino’s earnings announcements based on confidential information he acquired while working as an accountant in the company’s corporate office. The commission’s complaint said that Compton spread his trading across a number of different brokerage accounts that belonged to himself and various members of his family, and that his illicit profits topped $960,000.

“The SEC investigation uncovered that Compton allegedly accessed and reviewed Domino’s confidential data to prepare financial performance reports for senior management,” said Joseph Sansone, the chief of the SEC’s market abuse unit, in a statement. “Using innovative analytical tools, SEC staff exposed the defendant’s repeated misuse of this inside information and are now holding him accountable.”

Source: ‘Pizza accountant to pay $2M for insider trading’, by Daniel Hood, April 22 2022, Accounting Today

Professional behaviour

The fifth and final principle of professional behaviour requires accountants to ‘…comply with relevant laws and regulations and avoid any action that discredits the profession’ (Section 100.5e). This principle broadly requires accountants to engage in behaviours that are not only ethical from the perspective of other stakeholders relating to a business (customers, suppliers, employees, etc.), but also more generally behave in a way that will not bring the accounting profession into disrepute. Whatever the context, if an accountant is acting in a way that might bring his profession into disrepute, the accountant will be considered as being in breach of this principle.

Accountants must behave in a manner consistent with the profession’s responsibility to act in the public interest in all professional activities and business relationships and avoid any action or omission that may bring discredit to the profession. This includes actions or omissions which a reasonable and informed third party, having knowledge of all relevant information, would conclude negatively affects the good reputation of the profession. In addition, in marketing and promoting themselves and their work, members should not bring the profession into disrepute. Members should be honest and truthful and should not:

(b) Make disparaging references or unsubstantiated comparisons to the work of others.

Having considered the five principles, the next section looks at the five threats that accountants should avoid (threats) in order to more easily engage in ethical behaviours (i.e. the ethical principles discussed above).