4.6 Cash and Share Dividends

Rina Dhillon; Mitchell Franklin; Patty Graybeal; and Dixon Cooper

The Nature and Purposes of Dividends

Do you remember playing the board game Monopoly when you were younger? If you landed on the Chance space, you picked a card. The Chance card may have paid a $50 dividend. At the time, you probably were just excited for the additional funds. A Chance card from a Monopoly game indicates that the bank pays you a dividend of $50. (credit: modification of “Monopoly Chance Card” by Kerry Ceszyk/Flickr, CC BY 4.0)

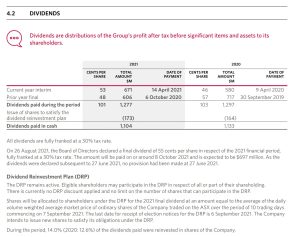

Similarly, shareholders who invest in companies are typically driven by two factors—a desire to earn income in the form of dividends and a desire to benefit from the growth in the value of their investment. The board of directors of companies understand the need to provide shareholders with a periodic return, and as a result, often declare dividends usually two times a year. For example, Woolworths Group Limited generally pays an interim dividend in April and a final dividend in September or October each year.

However, companies can declare dividends whenever they want and are not limited in the number of annual declarations. Dividends are a distribution of a companies’ earnings. It is important to note that dividends are not considered expenses, and they are not reported on the income statement. They are a distribution of the net income of a company and are not a cost of business operations.

Some companies choose not to pay dividends and instead reinvest all of their earnings back into the company. One common scenario for situation occurs when a company experiencing rapid growth. The company may want to invest all their retained earnings to support and continue that growth. Another scenario is a mature business that believes retaining its earnings is more likely to result in an increased market value and share price. In other instances, a business may want to use its earnings to purchase new assets or branch out into new areas. Most companies like Woolworths, however, attempt dividend smoothing, the practice of paying dividends that are relatively equal period after period, even when earnings fluctuate. When dividends are distributed, they are stated as a per share amount and are paid only on fully issued shares.

For companies, there are several reasons to consider sharing some of their earnings with shareholders in the form of dividends. Many shareholders view a dividend payment as a sign of a company’s financial health and are more likely to purchase its shares. In addition, companies use dividends as a marketing tool to remind investors that their share is a profit generator.

This section explains the two types of dividends—cash dividends and share dividends—showing the journal entries involved and the reason why companies declare and pay dividends, and the relevant dates that are important when issuing dividends.

Dividend Dates

A company’s board of directors has the power to formally vote to declare dividends. The date of declaration is the date on which the dividends become a legal liability, the date on which the board of directors votes to distribute the dividends. Cash dividends become liabilities on the declaration date because they represent a formal obligation to distribute economic resources (assets) to shareholders. On the other hand, share dividends distribute additional shares, and because shares are part of equity and not an asset, share dividends do not become liabilities when declared.

At the time dividends are declared, the board establishes a date of record and a date of payment. The date of record establishes who is entitled to receive a dividend; shareholders who own shares on the date of record are entitled to receive a dividend even if they sell it prior to the date of payment. Investors who purchase shares after the date of record but before the payment date are not entitled to receive dividends since they did not own the share on the date of record. These shares are said to be sold ex-dividend. The date of payment is the date that payment is issued to the shareholder for the amount of the dividend declared.

Cash Dividends

Cash dividends are earnings that companies pass along to their shareholders. To pay a cash dividend, the company must meet two criteria. First, there must be sufficient cash on hand to fulfill the dividend payment. Second, the company must have sufficient retained earnings; that is, it must have enough residual assets to cover the dividend such that the Retained Earnings account does not become a negative (debit) amount upon declaration. On the day the board of directors votes to declare a cash dividend, a journal entry is required to record the declaration as a liability.

Accounting for Cash Dividends

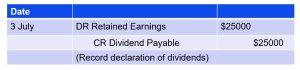

Assume that on 3rd July, Sydney Accounting’s board of directors declares a $0.25 per share dividend. As of the date of declaration, the company has 100000 ordinary shares issued. The dividend is owed to shareholders on record on 21 July and paid on 30 July. The total cash dividend to be paid is based on the number of shares outstanding is:

100000 x $0.25 = $25000

The journal entry to record the declaration of the cash dividends involves a decrease (debit) to Retained Earnings (a shareholders’ equity account) and an increase (credit) to Dividends Payable (a liability account):

While a few companies may use a temporary account, Dividends Declared, rather than Retained Earnings, most companies debit Retained Earnings directly. Ultimately, any dividends declared cause a decrease to Retained Earnings.

While a few companies may use a temporary account, Dividends Declared, rather than Retained Earnings, most companies debit Retained Earnings directly. Ultimately, any dividends declared cause a decrease to Retained Earnings.

The second significant dividend date is the date of record, 21st July. The date of record determines which shareholders will receive the dividends. There is no journal entry recorded; the company creates a list of the shareholders that will receive dividends.

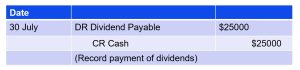

The date of payment is the third important date related to dividends. This is the date that dividend payments are prepared and sent to shareholders who owned shares on the date of record. The related journal entry is a fulfillment of the obligation established on the declaration date – 30th July; it reduces the Dividends Payable account (with a debit) and the Cash account (with a credit).

Reporting Cash Dividends

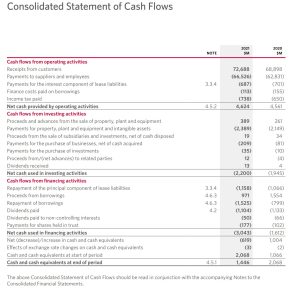

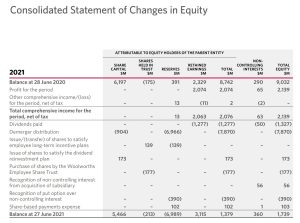

You will note in the above extracts of the statement of change in equity and cash flow statements that the dividends paid is $1277M and $1104M respectively. The difference of $173M ($1277-1104) is explained in Note 4.2 of the annual report as part of a Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP). A DRP allows a shareholder to take some, or all, of their dividend in the form of additional shares, and usually offered at a discount. The shareholder can nominate what percentage they wish to split between cash and shares. DRP are similar to share dividends but it is the shareholder’s decision to receive shares not cash rather than it being decided by the company and imposed on all shareholders with a share dividend. We now turn our focus on share dividends to better understand how to they are recorded in the accounting system.

Share Dividends

Companies that do not want to issue cash dividends (usually when the company has insufficient cash) but still want to provide some benefit to shareholders may choose to issue share dividends. When a company issues a share dividend, it distributes additional shares (ordinary shares) to existing shareholders. Share dividends are declared by a company’s board of directors and may be stated in dollar or percentage terms. Shareholders do not have to pay income taxes on share dividends when they receive them; instead, they are taxed when the shareholder sells them in the future. A share dividend distributes shares so that after the distribution, all shareholders have the exact same percentage of ownership that they held prior to the dividend.

Let’s look at an example using Sydney Accounting. Assume that Sydney Accounting Pty Ltd declares a 15% share dividend on 1 July to be distributed immediately. Sydney Accounting has 100000 ordinary shares originally issued for $6 and the share is currently trading at $10 per share.

This means that Sydney Accounting will distribute 15,000 new shares (100,000 x 15%), each worth $10 (current market price). So the value of the share dividend is = $150,000 ($10 x 15,000 shares) and will be recorded as follows: