11.2 Understand externalised costs for which organisations are responsible

Leanne Gaul

External costs are those which arise during the course of an organisation’s operations, but their existence may or may not be known to the entity. Additionally, in a traditional financial report, these are typically not recognised. To get a better understanding of this phenomenon it is best to use an example.

UIC, a worldwide professional association representing the railway sector, conducted a study of external costs generated by transport users including impacts such as congestion, air pollution, climate change, accidents, noise and supply chain process costs on the environment.[1] The difficulty in accurately reporting this information is directly related to the measurement of these external costs. Reporting boundaries required that some identified external costs were excluded such as air and noise pollution and congestion due to the difficulty of gathering data to adequately reflect the extent of these externalities.[2] UICs method for measuring performance over external costs was to use an external cost calculator which mimicked the capabilities of a competitors tool. Adverse consequences relate to the effectiveness of the tool, if its’ methods for calculation are erroneous this will impact the integrity of reporting for all users, internal and external.

The importance of accurately measuring an organisations external costs cannot be understated as it impacts organisational decision making processes.[3] Flawed data and consequently information (managerial reporting) with which an organisation approaches the reduction of external costs may result in ineffective outcomes, wasting an organisation’s limited resources. Inadequate managerial reporting may lead organisations to underestimate the impact of their external costs which may lead to a breach of Australian environmental law. The New South Wales Environment Protection Authority (NSW EPA) administers the EPA Regulatory strategy, policy, and compliance plan.[4] Under the protection of the Environment Administration Act 1991, the NSW EPA is responsible for investigating and reporting issues or allegations of non-compliance with relevant legislation. NSW EPA may use the follow two penalty instruments against breaching companies:

- an enforceable undertaking, which is a voluntary legally binding written agreement between the NSW EPA and the relevant company;

- fines commensurate with the financial advantage the offending company has gained over competitors by committing the environmental breach (Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 – POEO Act).[5] An example of this breach occurred in 2017 when Acciona Infrastructure Australia Pty Ltd polluted a creek in Nambucca Heads by discharging sediment laden water into a nearby creek, breaching s120 of the POEO Act. This discharge can lead to the decimation of localised aquatic plants and marine life and other adverse impacts to the ecosystem.[6] The fine awarded against Acciona was $15,000.[7] In Australia the Environment Protection Authority comes under different jurisdictions; the national/commonwealth agency (Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment) and each state and territory has their own EPA.[8]

The risk of breaching environmental legislation not only has a direct cost but may also impact reputation and profitability. Hence it is in the best interest of a business to be proactive in its approach to sustainability and operate transparently. How might a company like Acciona become more proactive and avoid the fines that was imposed on them by the EPA? Acciona could have treated the sediment laden water to clean water prior to discharging it or to have a third-party organisation do this for them. It may prove expensive to purchase equipment to treat the water so the latter option may be best in the short term. In going with the latter option, Acciona would need to ensure the third party properly treats the waste, so they would need a clear outline of the process. The business would seek a contractor that has high quality standards, reputation and appropriate accreditations. To be sustainable does not mean a firm ceases to be responsible once it leaves their premises. Relationships with poor waste management facilities can lead to reputational damage to customers. In addition, the NSW EPA has various guidance’s on managing liquid waste to help businesses meet compliance requirements. As breaches are added to the NSW EPA websites, simple searches can lead interested parties to find this information. So, it is in the best interests of the company to be accountable for their actions and be as transparent as possible to reduce impacts to their reputation and relationships.

It is important to note that quantifying external costs can be difficult as they fall into both quantitative and qualitative measures. For example, quantifying clean up costs is a simple job of accounting. However, loss of ecosystems beyond remediation, loss of recreational areas for communities, loss of indigenous traditional sites and loss of biodiversity has a broader effect. Putting a figure on external costs can be difficult as it varies by location and may be extensive when considering social costs. The National Water Commission in Australia has released a report titled Externality pricing in the Australian water sector. The report noted issues including a failure to define positive (when a benefit spills over) and negative (when a cost spills over) externalities, calling on government intervention to improve outcomes for society. As it currently stands there is limited or no existing guidance over organisations measuring and transparently reporting pollution and the associated costs. Additionally, quantification of impacts may be difficult to value for broader society, however it may still be material to stakeholders and should be included in reports.

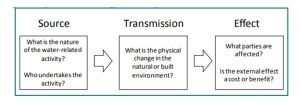

One way in which this can be done is by identifying the externalities. The diagram below provides a method to define the key elements of an externality:

Source: Discharge of sediment laden water into the local water supply.

Transmission: Destruction of local aquatic plant life and marine life and damage to downstream ecosystems.

Effect: The affected parties include marine and local fauna biodiversity (they are a stakeholders), local community and residents along the creek and attached waterways – downstream inhabitants. These are external costs.

[1] UIC. (2015). External costs. https://uic.org/support-activities/economics/article/external-costs. (accessed 26 September 2022).

[2] ibid

[3] Zinke, T., Schmidt-Throe, G., & Ummenhofer, T. (2012). Development and Application of External Costs as part of the Sustainability Assessment of Transportation Infrastructure. Beton- und Stahlbetonbau, 107(8), 524–U139. https://doi.org/10.1002/best.201200021

[4] New South Wales Environment Protection Authority (NSW EPA). (2022). Policies and guidelines. https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/licensing-and-regulation/legislation-and-compliance/policies-and-guidelines. (accessed 26 September 2022).

[5] New South Wales Environment Protection Authority (NSW EPA). (2022). Policies and guidelines. https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/licensing-and-regulation/legislation-and-compliance/policies-and-guidelines. (accessed 26 September 2022).

[6] New South Wales Environmental Protection Agency (NSW EPA). (2022). Infrastructure company fined $15,000 for environmental breach. https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/news/media-releases/2017/epamedia171211-infrastructure-company-fined-$15000-for-environmental-breach. (accessed 26 September 2022).

[7] ibid

[8] National Environment Protection Council. (n.d.). Jurisdictional Agencies. http://www.nepc.gov.au/about-us/jurisdictional-agencies. (accessed 26 September 2022).